Female Filmmakers In Focus: Zeinabu irene Davis on “Compensation”

An interview with the filmmaker behind the Chicago-set indie landmark.

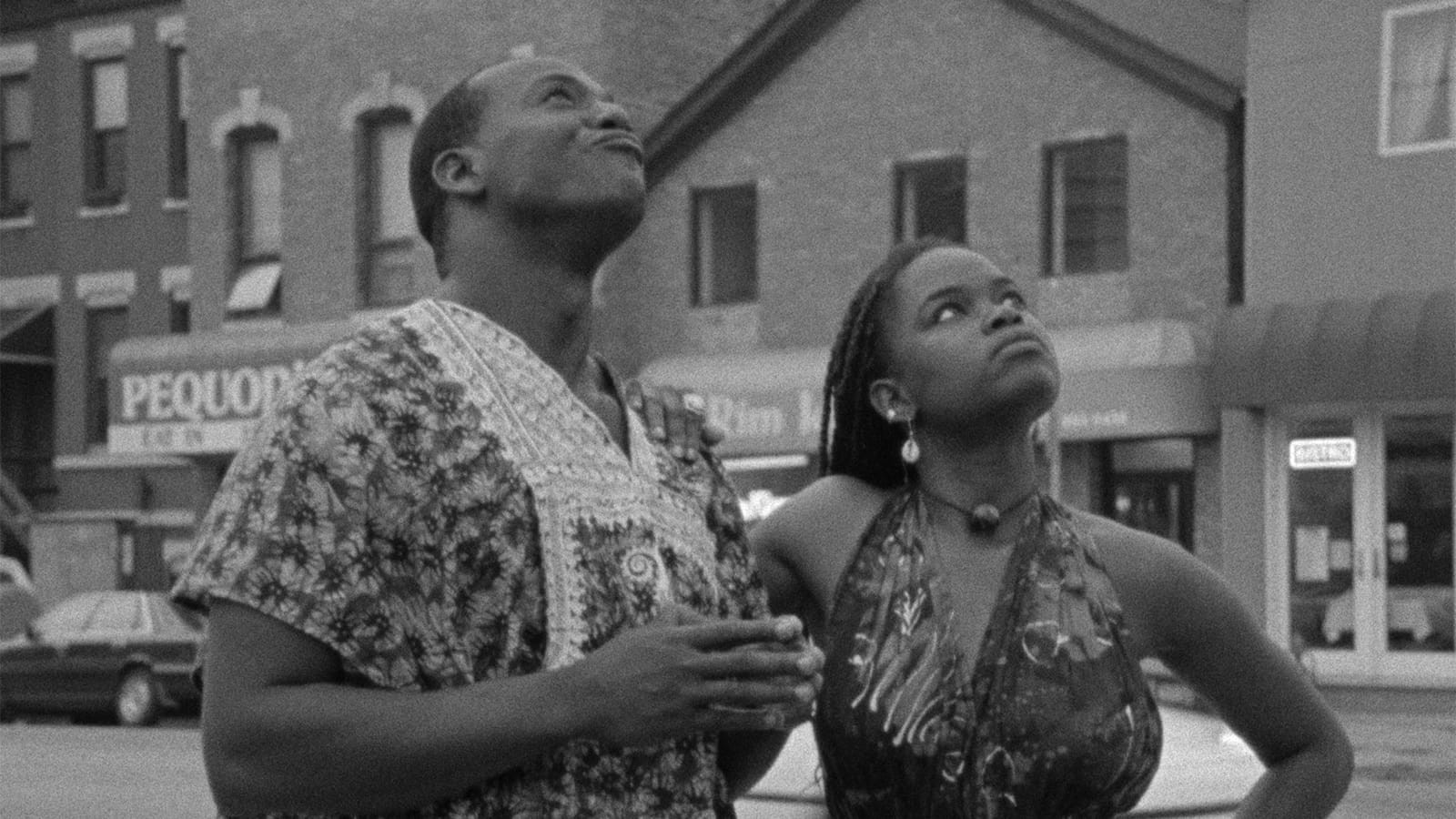

The title of Zeinabu irene Davis’s landmark independent film “Compensation” comes from Paul Laurence Dunbar’s 1906 poem of the same name. It follows the parallel love stories of two lovers—a deaf woman (Michelle A. Banks) and a hearing man (John Earl Jelks)—in both turn-of-the-century and modern-day Chicago. As the film crosscuts between the story of Malindy and Arthur, who are living in the earlier twentieth century, and Malaika and Nico, living during its final decade, Davis skillfully weaves in a hundreds years of Black American history through the use of archival photography brought to life through sound, open captions, and music. Ultimately, her film reveals as many similarities as it does differences.

Filmmaker Zeinabu irene Davis received her undergraduate education at Brown University, later graduating with both an M.A in African studies and MFA program in film and video from UCLA, where she was a member of the cohort now known as the L.A. Rebellion, along with filmmakers like Charles Burnett, Julie Dash, Alile Sharon Larkin, and Billy Woodberry. For the last several decades has taught at many colleges and universities, including Antioch College in Ohio and Northwestern University in Illinois. She currently works as a professor in the Department of Communication at the University of California, San Diego.

While working at Northwestern, “Compensation” was filmed on 16mm black and white film in and around the Chicagoland area in 1993, with a crew that included many of Davis’ university students, and was 85% composed of women. After a long post-production process, the film eventually debuted at the Atlanta Film and Video Festival, before screening at the1999 Toronto International Film Festival and the 2000 Sundance Film Festival. This new 4K digital restoration, which Davis calls a “rejuvenation,” was undertaken in collaboration between the Criterion Collection, the UCLA Film and Television Archive, and Wimmin with a Mission Productions.

In the 25 years since its initial, stilted, release, “Compensation” has found new audiences and resonated with younger generations. After attending the restoration’s recent screening at the Chicago International Film Festival in October, RogerEbert.com contributor Cortlyn Kelly wrote the film “is overflowing with romance, poeticism, innocence, and heartache,” and that, “as the revitalized film recirculates, there is also regenerative representation for non-hearing individuals. The Black community to independent filmmakers to those battling autoimmune illnesses will all be able to resonate with reflections of themselves on screen.” Just a few weeks later, the film was added to the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

For this month’s Female Filmmakers in Focus column, RogerEbert.com spoke to Davis over Zoom about the film’s long journey towards theatrical release, the digital restoration process, working on the film’s new captions, excavating Black Chicago history through cinema, and the importance of finding your community as a filmmaker.

You’ve called this release a rejuvenation, and I would love to hear what the journey has been like for you from that early Women Make Movies educational release to this new Janus Films theatrical release.

When “Compensation” first came out it was at the Toronto International Film Festival in late 1999 and the Sundance Film Festival in early 2000. We had hoped that there would be theatrical distribution, but there really wasn’t. In fact, I distinctly remember potential distributors running out of the screening spaces after the first 15 minutes when we didn’t have any dialog. One happy memory I have at that time was actually Roger Ebert being there. He was very supportive of the film and the cast at that time, and he wrote a very sweet, you know, mini review at that time. But the only opportunities we had for the film, really, was for it to go into educational distribution. Women Make Movies was the one who kind of kept it going for me for the last twenty-five years.

What really started things going again is that Ashley Clark did a ’90s series at the Brooklyn Art Museum. That really got attention for the film again. And another critic, Richard Brody from The New Yorker, kept writing about the film. That really set the ball rolling. Then Ashley joined Criterion and helped program the retrospective of my films on the Criterion Channel. Then, they offered an opportunity with Janus to work on a restoration of the film. It’s taken a long time for that to happen, but it finally has happened.

Also, I want people to know that “Compensation” was selected for the National Film Registry in 2024. It was a big honor. And I’m very humbled, because there’s only 800 films in that collection and now our little alternative independent film is in there for all time. So it’s a wonderful thing.

When did the work on this restoration take place?

We did most of the work in the last year. I spent most of this summer working with Alison O’Daniel, another filmmaker who made “The Tuba Thieves,” on the captioning process. Because the captioning now can be so much more inclusive. It used to be limited to thirty-one characters on two lines that the subtitles allowed back in the early 2000s. So now we can be expansive and more inclusive. We could include where the music happens in the film, which we put in the upper left corner, and then in the upper right corner, we put the sound effects, and then we kept the dialog captions on the bottom, but we place the captions for the characters closer to the character who’s speaking in the frame. So it is all much more inclusive and accessible for both deaf and hard of hearing audiences.

But it’s also for hearing audiences because you can really pay attention to the sound effects and the music when it comes in. For the audiences I’ve been experiencing the restoration with so far, it’s a different kind of experience because, due to the new captioning, you are really immersed in the world of the film. So I’m grateful for that.

Did the digital restoration process also allow you to add more layers of sound?

No. I’m an old school filmmaker. When the film is cut, the film is cut, even though I could have done blah, blah, blah, no. What happened was that because the 16 millimeter was a mono track, so the sound was squashed. But I spent at least three months on the sound originally. I love sound. I spent about three months working on the sound at Maestro-Matic, which was a sound studio in Chicago with an amazing team, Mark and Dave Carlson.

Mark came from a more experimental background, so we would do crazy stuff. We put a microphone in a condom and put it inside of the bathtub and swished it around to kind of get some of the sound effects. Because talking to Michelle about her experiences with sound as a deaf person, she would describe sound that seemed like being underwater. We tried to apply that to the concept of our sound recordings. It’s more in the contemporary part of the film. There’s a more experimental section where you see the train tracks going overhead, and Nico and Malika are in a different mode, so there’s more of those sound effects.

I think I had probably about at least 20, maybe as many as 24 tracks of sound sometimes when we were doing the original mix, but then it got squashed. So now, since it’s in 4k and stereo sound, you can actually hear much more of what is in the film than you could when it was first released in 2000. So I didn’t add any sound, but this process has made the sound fuller because you hear it on speakers.

The only thing I was able to do in the restoration process–I was geeking out because I was at Crest Digital in LA, and these are the big boys and girls; they do films “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer” and all that kind of stuff–so I was in those rooms, and we played around with adjusting some of the sound effects to go from left to right when a train goes by into the film. We just increased the bandwidth of some of the sound effects, but we didn’t change anything. Maybe we eliminated some pops from the optical track that may have been in the original sound. But other than that, it’s pretty much the way it was back then.

You also have three different very specific genres of music that bring the film to life. You have the Ragtime, you have the African music, and you have Chicago House music, which is amazing. I love the sequence where they’re dancing to the House music. I imagine those were three very specific artistic choices. Could you talk a bit about how you landed on those three kinds of music and what you were hoping to do in terms of connecting them through history? So much of the film is about connecting the past to the present and the present to the past.

Thank you for pointing that out, because not that many people ask about the music. So I appreciate you doing that. First came the ragtime music, because that was from the turn of the century and the story is set at the turn of the century. So we wanted to have the music reflect the time period for which we were talking about. So I always wanted to have some Ragtime in the film. And I was very lucky that Reginald R. Robinson happened to live in Chicago, and he’s the Ragtime master. So we started working with him. At the time he was a fairly young composer, and he hadn’t done any other film work yet. It was a really amazing process to work with him and show him scenes and let him make suggestions to me. Sometimes they worked and sometimes they didn’t work, but we did get it. I felt like we did have good collaboration in getting the spirit of the music into the film,

With the African music, Chicago is a music town. So I was gifted with being able to work with Atiba Y. Jali on the African music and the West African based percussion. Atiba had all these different instruments at his studio, so we went into the studio and played around with stuff. I think both Atiba and Reginald did meet and talk about the music overall. Atiba also did the House percussion. He made that music as well. Then there was Asma Feyijinmi, who is one of my best friends, who plays the dancer in “A Powerful Thang,” she did the udo on the score. I love the udo because it’s a gourd that has water in it, so the sound, again, reminded me of what it would sound like if it was underwater. So we incorporated that, along with her partner James E. Rohlehr, who played the bass guitar on that opening track of the intro to the Chicago scene, because it does have a Blues sensibility to it.

I do think that it’s like an amazing thing that a film can incorporate so many different artists in it. I wanted to exploit that as much as I could, as an alternative, independent filmmaker. I really wanted to bring in all these different types of musicians and pieces into the fabric of the film as much as possible. So I’m just grateful I was able to work with so many great artists.

Also, we are actively trying to release a soundtrack album for “Compensation” as well. It will primarily just be the Ragtime score, but we are working on it. Hopefully that’ll happen so people can listen to it afterwards, because I get to listen to it, but nobody else does. Reginald R. Robinson has more pieces that were beautiful that we wanted to include in the film, but we just didn’t have time for it. So the soundtrack will also have bonus tracks of music that we recorded but couldn’t use in the finished film.

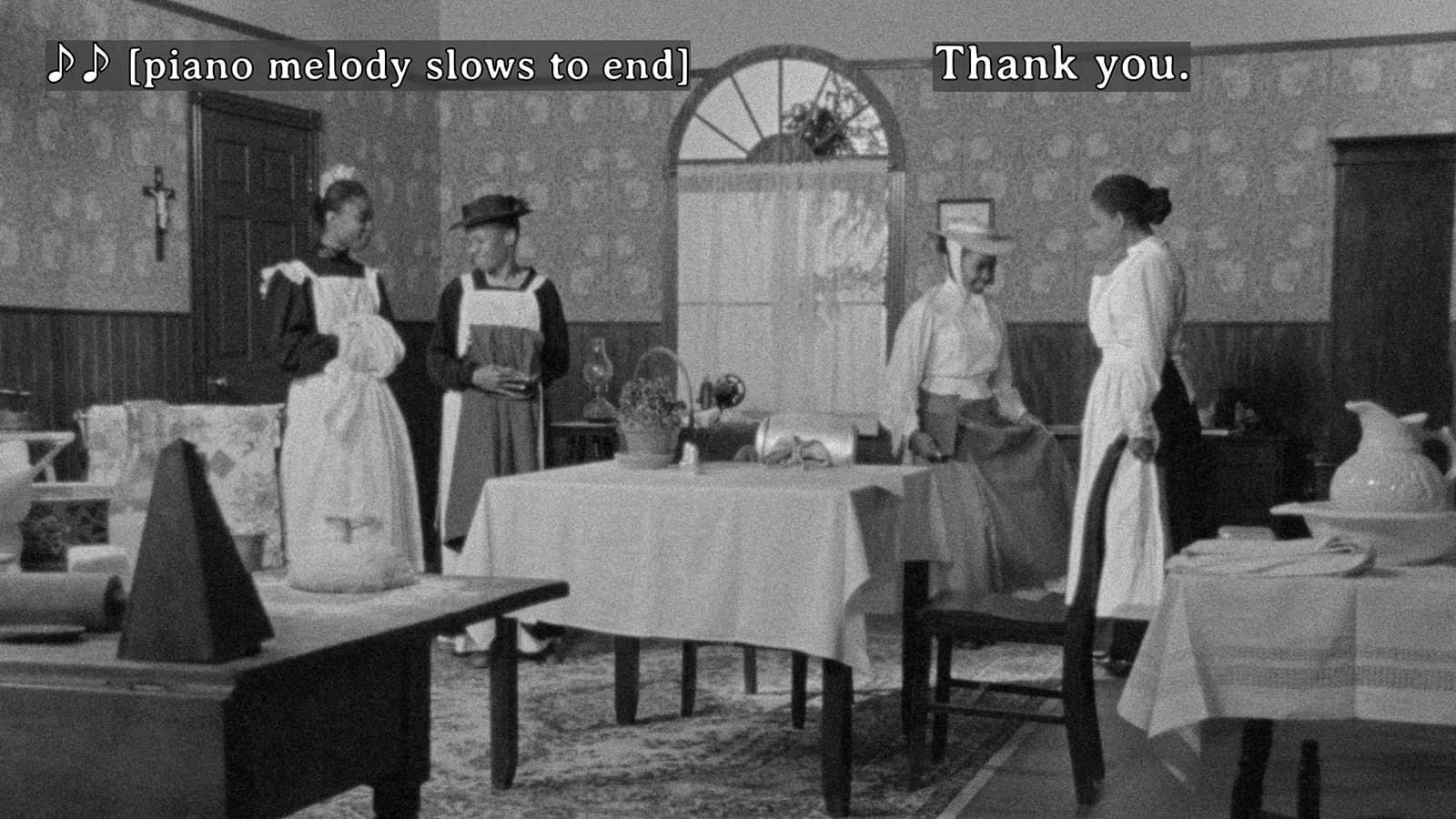

In the 1910s section, Malindy and Arthur go to a nickelodeon to watch “The Railroad Porter,” which you recreated, but is based on pioneering Chicago filmmaker William Foster‘s film of the same name. How did you first come across his work? When did you know you wanted to honor that legacy of Chicago?

That was a very deliberate choice because both you and I share the experience of going to film school, and you know that in film school they show you the usual suspects of classic Hollywood film. They’re really not as inclusive of other people’s experiences or what the world was doing at the beginning of cinema. It’s always so U.S. and white male based. So that was a deliberate choice to use “The Railroad Porter” as a way to open up that whole era of early Black cinema, or cinema of alternate places from other parts of the world.

I did research looking for alternatives, because we got bludgeoned by the D.W. Griffith and “The Birth of the Nation” when we were in film school. The professors would talk about the film’s innovations, but they wouldn’t talk about the racism that was inherent in the film and the damage that that did to various Black communities in the country when people first saw that film. I think it was important for me to go back and see if there was a film that we could include. But unfortunately, you know, because most of those films were on nitrate film, which eventually disintegrates or blows up, we basically couldn’t find anything that was intact from that time period.

Luckily, there are records of those films that were recorded in the Chicago Defender. That was where I saw the listing for William Foster’s “The Railroad POrter” as one of the first films by a Black director. In reading the synopsis, I said, “Okay, we can recreate this recreate the film.” So that’s what we did. And we put a Zeinabu twist. In our version the woman has a gun and is chasing the other two guys. The original synopsis just has the slapstick chase between the railroad porter and the husband, who we made into a police officer.

I was also very lucky, because we had two icons of Chicago activism, Lisa Brock and Otis Cunningham, as the actors. They’re folks who have been long time friends of mine. One of the impetus of the LA Rebellion filmmakers, of which I’m a part, is to use your community to make work. So when I don’t have resources, I use what I have available to me from my community. Otis and Lisa were very generous and loaned us their backyard for the film too. So of course, I put them in there. It’s an easy scene, because you can be too over the top. You don’t have to be a professional actor. So in that scene, it’s Otis and Lisa, and also Reginald, the composer. He’s the one who’s playing the railroad porter. He got a kick out of being in that. Then, of course, it was really fun to watch him compose to that particular section as well.

I also saw that Yvonne Wellborn, from Sisters in Cinema, was an associate producer and assistant director. How did you two first start working together?

I met Yvonne, pretty much right after I moved to Chicago. I worked for a couple of years in Yellow Springs, Ohio, and then I was offered a teaching position at Northwestern in 1991. So when I was moving to Chicago, she had just come back from living in Taiwan, and entered into the school at The Art Institute. We don’t exactly remember when we first met. We just know that one of the ways that we got together and became good friends was through being on the board of Women in the Director’s Chair, which was a nonprofit organization that did advocacy for women filmmakers. She and I were on the board early on, and worked together through that. Then she came and got her PhD at Northwestern. I was one of her advisors for her dissertation, but at the same time she and I were colleagues, not just a student-professor kind of thing. She worked on “Compensation” as the assistant director and associate producer, and another woman, Dana Briscoe, who was also in the program at school The Art Institute, worked on the film as associate producer and as the co-editor with me on the film. There was a lot of talent in Chicago, so used the people who were around me at the time.

A few years ago your film “Cycles” also screened as part of the Sojourner Truth Festival of the Arts, which Yvonne had a part in organizing.

Yes.

“Compensation” brings archives into the present day and shows that history is this living being. And I feel like your film also continued to evolve as a sort of living being. Then this community that you’ve been a part of, all of your films keep coming back. We’re at this point where your film is finally going to be in theaters across the United States. So many of these short films are available for wide audiences to watch. I’d love to hear your thoughts on how this community has kept supporting itself and kept pushing its films forward?

I think you know the importance of that Sojourner Truth Festival in 2023. It was monumental and I’m so grateful to Yvonne and Allyson Nadia Field and Hayley O’Malley, because that was a lot of work and a lot of fundraising, but they really did a great job. They really did so much work pulling that together. And I think what was beautiful about that experience was that we all realized that, yes, we’re filmmakers, but there were also theater people, and there were also written word poets and authors who all came back for that experience. So you could see that there was this trajectory of Black women working in the arts that has evolved from that very first Sojourner Truth Festival in 1976, where Faith Ringgold, Michele Wallace, Patricia Jones, Margo Jefferson, and Monica Freeman brought folks together. It was clear we had a lineage.

So I think knowing that lineage and making sure that it gets passed on to the next generation of filmmakers that they also know about these films and the contributions of the filmmakers and artists who did work before them. I think that was what was so important. And then having the films distributed by Third World Newsreel, or Women Make Movies, and Video Data Bank. Those small nonprofit organizations kept us going because the work would be seen in schools or in festivals or occasionally broadcast on television. That’s how I think the work keeps going and people continue to be exposed to it.

For this column, I’ve actually spoken to several Black women filmmakers whose films in the 90s were not really supported by distributors–Cauleen Smith, Ayoka Chenzira, Bridgett M. Davis. All four of you–and even Leslie Harris, whom I have not spoken to, but I love her film “Just Another Girl on the IRT”–all five of you had these films that were different; different from each other, different from what was coming out, and somehow it’s taken another generation, I guess, to bring them back. And they’re still speaking to audiences. I’m curious about why these films were neglected in the ’90s and why they still so beautifully speak to audiences today.

I’ve been very grateful that I’ve been able to see most of the restorations of all those films and sometimes had the opportunity to see them in the theater again, like Ayoka and Bridgett’s films, which recently had theatrical releases here in San Diego. Cauleen Smith’s “Drylongso” is also available through the Criterion Collection. Leslie Harris’ film I haven’t seen in a long time, but I would love to watch that one again.

I think Paramount put out a Blu-ray a few years ago but they didn’t do any press around it, which was disappointing, but it is available, thankfully.

That’s good to know, because I teach a class on Black women filmmakers, so it’s good to know that films are available. I think what we were trying to do was…I just think we were ahead of our times in some ways, and I think that it’s taken, I guess it’s taken thirty years for the rest of the world to catch up. I’m very grateful that all the films that you’ve mentioned, all the films and filmmakers that you mentioned, we’re all still doing work for the most part, and all the films that we made are evergreen. They still speak to different audiences.

I love seeing the power of Caribbean folk who see Ayoka’s film “Alma’s Rainbow” and respond to it. I love seeing people respond to the early inclination towards Black Lives Matter when you watch “Drylongso” or the way Bridgett’s film tackles body issues but is also so funny. I did not remember how funny that film was. And then my film, it was also filmed in the 90s, the thing that cracks me up as someone who’s from that time period and earlier is that, my daughters or my students watch the films, they’re always so enamored with the way we communicated with each other back then, because we didn’t have cell phones. Also the way they react to the clothes and the fashion. My daughters are angry with me that I still don’t have some of those clothes in my closet because they would wear them. They really like the fashion.

The beautiful thing that was really cool was seeing audiences at the New York Film Festival. I really thought that the audiences for “Compensation” were going to be mostly like gray haired folks like me or something. But it wasn’t. There were twenty-somethings or thirty-somethings in the audience. I think it’s just this hunger or desire to see something different, something more original that you don’t get unfortunately, for better or for worse, by so many superhero movies or the way everything has to be derivative IP of something that we’ve already seen before. So I think seeing these films now lets the audience know that there’s the possibility for different voices and different kinds of images that we’re not seeing right now. Even in alternative, independent filmmaking, I don’t think you get to see the kinds of things that we were doing for the most part.

And if they are, they’re still being neglected. Earlier, you mentioned that the lineage was being passed on to the next generation of filmmakers. What would you like to tell them?

Please form a community of people who will support you. That’s really critical. It can be your birth family, but it could be your chosen family or friends or just colleagues. Because it’s so hard to do this work, you need people around you who can offer you support in any way possible. Your relatives can cook food for the crew when you’re shooting. Or, if you’ve got a wealthy relative, they might be able to loan you some money so you can make your film. Or you can do crowdfunding-type efforts. But I think it’s important for people to realize that they need to have a community around them.

The other thing I’m just begging my students and younger filmmakers to do is to watch films as they were meant to be seen in the theater so you can see them big and not on your phone. I fail students who tell me they watched “Daughters of the Dust” on their cell phone.

No, that’s not right.

Julie Dash really did not make that film for you to watch it on a cellphone. I know some films feel like they are okay to watch on a cellphone, but that’s not one of them.

Definitely not.

I think the biggest issue or concern for me is that people need to see as much world cinema and as much alternative, independent cinema as possible, and go to film festivals, so you can keep seeing new works. I’m always excited and inspired when I see other people do great work and what the possibilities are. I haven’t been able to make that many films, but what I have been able to make, I’m really proud of those, and I want more people to be able to experience the works as much as possible. When we were in film school, we had opportunities to see this stuff because we had to watch them in class. But I think it’s important for your development and your growth as a filmmaker to continue that education after you’re out of the film school environment.

_Agata_Gładykowska_Alamy.jpg?#)