It’s Not Just Denali. Here Are 4 Other Alaskan Destinations to Know by Indigenous Names

Many places in Alaska have a long history of going by two (or more) names.

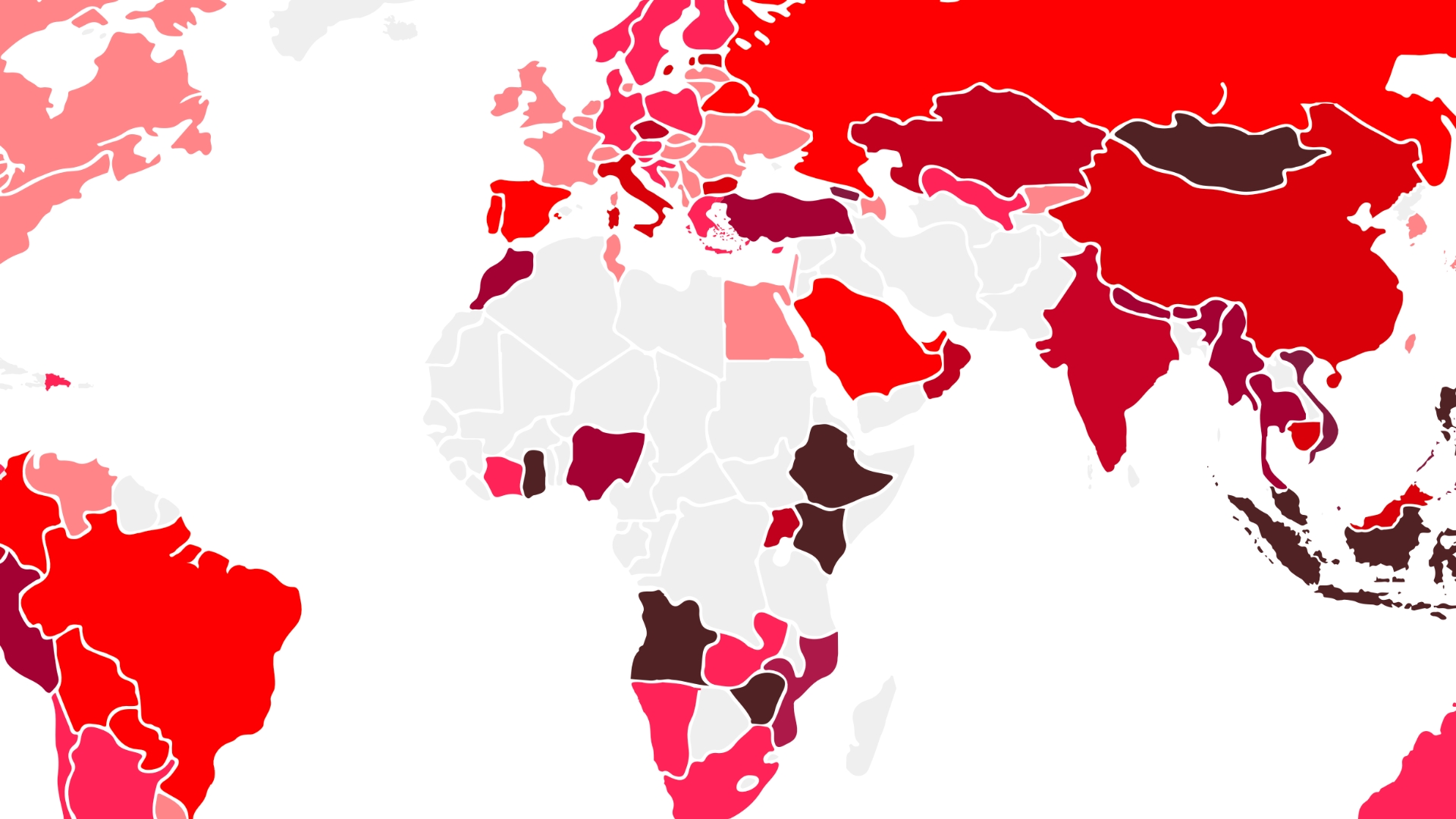

Donald Trump was sworn in as president of the US only 10 days ago, but has undertaken a flurry of executive orders. As of January 29, he’s signed 38 — more than any other president has signed so early into his term.

While many are considered controversial, one that has received extra attention for being particularly out of left field is an order to rename geographic features around the US. Trump signed an order to change the name of the Gulf of Mexico to the “Gulf of America.” It’s underway, but will be changed only in the US, as the Gulf of Mexico is the globally accepted name. But also attached to that order was a directive to change the name of Denali, Alaska’s 20,310-foot-tall peak and the highest in North America, to its former name, Mount McKinley. It went into effect on January 23.

Denali has been central to a longstanding naming dispute for decades. For time immemorial, it was known as “Denali.” It means “the high one” in the Koyukon Athabascan language — the language spoken by Indigenous people of that region. It was renamed Mount McKinley in 1896 by a prospector honoring then-presidential candidate William McKinley, though McKinley was from Ohio and never visited Alaska. In 2015, the Obama Administration restored the name to Denali as a way to acknowledge its Indigenous heritage.

Trump backed up his decision to take away the Indigenous name by claiming that McKinley was “a very good, maybe a great president” and that “President McKinley made our country very rich through tariffs and through talent—he was a natural businessman.” He claimed changing it to Denali was an insult to the state of Ohio, but hasn’t commented on the potential insult to Alaskans caused by changing it back.

Thus far, the decision hasn’t been popular with Alaskans. Alaska’s US Senators, Lisa Murkowski and Dan Sullivan, along with State Senator Scott Kawasaki, have expressed strong opposition, and historical scholars have also opposed the change. It’s also a departure from efforts of the US Board on Geographic Names, which has worked over the last decade toward restoring native names for natural places and features.

However — while Denali’s name change is in the news the most, it’s not the only impressive feature in Alaska still officially known by its non-native name. Here are four other places in Alaska worth seeing, along with their historic names and why they matter.

Mount Saint Elias, or Was’eitushaa

Photo: jet 67/Shutterstock

Mount Saint Elias, straddling the border between Alaska and Canada’s Yukon Territory, stands as North America’s second-highest peak, reaching an elevation of 18,008 feet. Danish-born Russian explorer Vitus Bering is credited with discovering the mountain on July 20, 1741, which is considered the “Feast Day of St. Elias” — hence the name.

The only problem with that is that Bering didn’t discover Mount Saint Elias. The indigenous Tlingit people had already named the mountain “Yasʼéitʼaa Shaa” or “Was’eitushaa,” translating to “mountain behind Icy Bay,” thousands of years earlier. As of early 2025, there are no official movements underway to restore the traditional name, though the National Park Service acknowledges the name “Was’eitushaa” in many of its official public materials.

Today, Mount Saint Elias is split between Wrangell-St. Elias National Park on its US side, and Kluane National Park and Reserve on the Canadian side. While summiting the mountain itself is a formidable challenge only for experienced mountaineers, the surrounding areas provide a wealth of activities. You can see Was’eitushaa from several visitor centers in the park, including those at the historic Kennecott Copper Mine. Many trails around the park offer stunning views of the Wrangell Range, though plenty of flightseeing tours are also available from companies like Wrangell Mountain Air, for visitors who don’t have time to make the long journey into the remote park.

Mount Foraker, or Sultana

Photo: Bob Pool/Shutterstock

Mount Foraker, standing at 17,400 feet, is the third-highest peak in the United States, just after Denali and Mount St. Elias. It’s also close to Denali, located just about 14 miles to the southwest. That’s probably why the Indigenous Koyukon people called it either “Sultana,” meaning “the woman,” or “Menlale,” meaning “Denali’s wife.” Despite this, in 1899, a US Army lieutenant renamed it Foraker, in honor of a US senator also from Ohio. Like Mount St. Elias, there are no official efforts underway to rename it, though many Alaskans continue to honor the traditional name Sultana.

Like nearby Denali, summiting Mount Foraker is a task best reserved for experienced, high-level mountaineers. However, anyone can see the snow-capped peak from quite a ways away. Around Talkeetna (the gateway town to Denali National Park), there are great views from the Talkeetna Spur road just south of town and from Talkeetna Riverfront Park. However, you can often see Mount Foraker from as far away as Anchorage, given its massive scale. There are excellent views of the range from within Chugach State Park (about 30 minutes from Anchorage) and from the summit of the city’s Flattop Mountain. You’ll have excellent views if you drive the George Parks Highway between Anchorage and Fairbanks, too.

Where to stay: The Most Popular Airbnbs Within Driving Distance to Denali National Park

Seward, or Qutalleq

Photo: reisegraf.ch/Shutterstock

At a roughly three-hour drive from Anchorage, Seward is one of the most popular tourist towns in Alaska. Not only is it in a gorgeous coastal setting on the tip of Resurrection Bay, but it’s also the gateway to Kenai Fjords National Park. It was named Seward in 1903, in honor of William H. Seward. He was the Secretary of State under President Andrew Johnson and orchestrated the purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867.

Before 1903, the area was called “Qutalleq,” named by the Indigenous Alutiiq people and meaning “Big Beach” in their language. In 1902, the founder of the Central Alaska Railway decided to route a railroad through the area, renaming it Seward as he thought it needed a more “official” name. Many people of Alutiiq heritage still live in Seward, which is also home to the Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute research facility.

Today, Seward sees about 250,000 visitors a year, most of whom come in the summer to visit the park or take advantage of the area’s fantastic recreational fishing. Visitors in 2025 can attend the quirky Seward Mermaid Festival in May, or take advantage of summer tours ranging from Kenai Fjord day tours to whale- watching trips, fishing expeditions, or even guided overnight camping trips on nearby coastline.

Where to stay: 11 Airbnbs in Alaska for a Gorgeous Summer Vacation

Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, or Sit’ Eeti Gheeyi

Photo: Danita Delimont/Shutterstock

In 1794, a survey team from the H.M.S. Discovery, led by Captain George Vancouver, documented the area as a mere indentation in the coastline, filled mostly by a massive glacier extending over 100 miles from the St. Elias mountain range. By 1879, naturalist John Muir observed that the glacier had retreated more than 30 miles, revealing a bay. That transformation inspired the name “Glacier Bay,” which was officially given to the region in 1880 by a US Navy captain.

Well before the late 1700s, the Huna Tlingit had occupied the area. They called it “S’e Shuyee” or “edge of the glacial silt.” But according to park historians, around the year 1700s, the glacier began to move forward, quickly forcing the Huna Tlingi away from their homes. They returned decades later when the glacier had receded, at which point the land had been carved into a huge valley. At this point, they renamed it “Sit’ Eeti Gheeyi” or “the bay in place of the glacier.”

In 1925, then-President Calvin Coolidge declared it a national monument, and it was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979. It became Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve in 1980, and a UNESCO biosphere reserve in 1986. Since 1994, it’s been co-managed between the National Park Service and Indigenous land owners.

For visitors to the Bay, exploring by boat is one of the most popular options, with tours that range from large cruise vessels to small-group kayak excursions. However, there’s a huge range of on-land activities, too, including hiking trails that meander through lush temperate rainforests and along rugged coastlines. Wildlife watching around the coastlines is also hugely popular.

Birdwatchers will be glad to know the protective efforts of Indigenous, state, and federal agencies have kept the park’s environment in pristine condition, and more than 27 species of bird have been recorded within its boundaries. Anyone interested in learning more about the region’s fascinating geologic and cultural history should visit the Huna Tribal House, which hosts guided programs and cultural demonstrations during the summer months. ![]()