Inside the Private Astronomy Village Hidden in the Darkest Part of Georgia

Expect no lights, minimal sound, and very few people.

Deerlick Astronomy Village in the East Central Piedmont region of Georgia seems a long way from everywhere, even if you live only 30 miles away from it like I do. The drive from my town of 3,300 people passes even smaller towns along unlit two-lane roads, going through a wide expanse of towering pine forests; it feels akin to going through a time vortex where the developed world fades away. And that’s exactly how the stargazing residents of Deerlick Astronomy Village want it: No lights, minimal sound, and very few people.

Deerlick, named after the Deer Lick grouping of galaxies visible in the Pegasus constellation, was founded in the mid-aughts by members of the Atlanta Astronomy Club. They were looking for the best place near Atlanta to view the nighttime sky under true dark sky conditions, and found it in Taliaferro County, about 90 miles away. Taliaferro (pronounced like “Oliver,” but with a “T” in front) is one of the least-populous counties east of the Mississippi River.

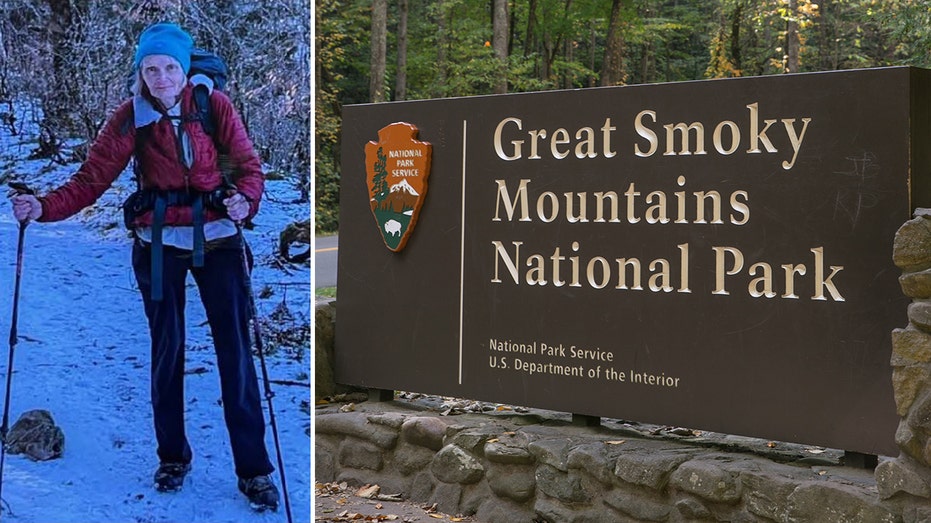

The road to Deerlick Astronomy Village. Photo: Blake Guthrie

“We wanted a safe place with permanent set ups and dark sky rules,” co-founder and part-time resident Erik Benner told me when I visited his Deerlick home. “This is one of the darkest spots on the East Coast outside of being in a swamp, and no serious astronomer wants to set up their high-end equipment in the middle of a humid swamp.” Benner’s home includes a private observatory with a retractable roof, though it’s not unique to him: Most of the village’s residents can push a button and roll their roof back to reveal the night sky.

Deerlick Astronomy Village’s dark sky rules are strict. After dark, no white lights are allowed anywhere on the property, including headlights. Guests and residents must drive slowly with headlights off, using only the parking lights to navigate lanes marked by tiny red lights. This slow speed limit also keeps dust from billowing up from the gravel roads around the viewing areas. Even the windows on all structures must have blackout curtains, so no inside light gets out.

Deerlick is surreal after dark with its blackout conditions, like being in an abandoned place – yet there are people all around in the quiet darkness looking at planets, stars, galaxies, and more. The star party goes on most nights until just before sunrise. But it’s not an actual party in the standard sense, as the greatest sin one can commit is shining a light or doing any actual partying after the roof comes off. “We’re very serious about what we do,” says Benner. “This isn’t a place for college students to come drink and see some stars.”

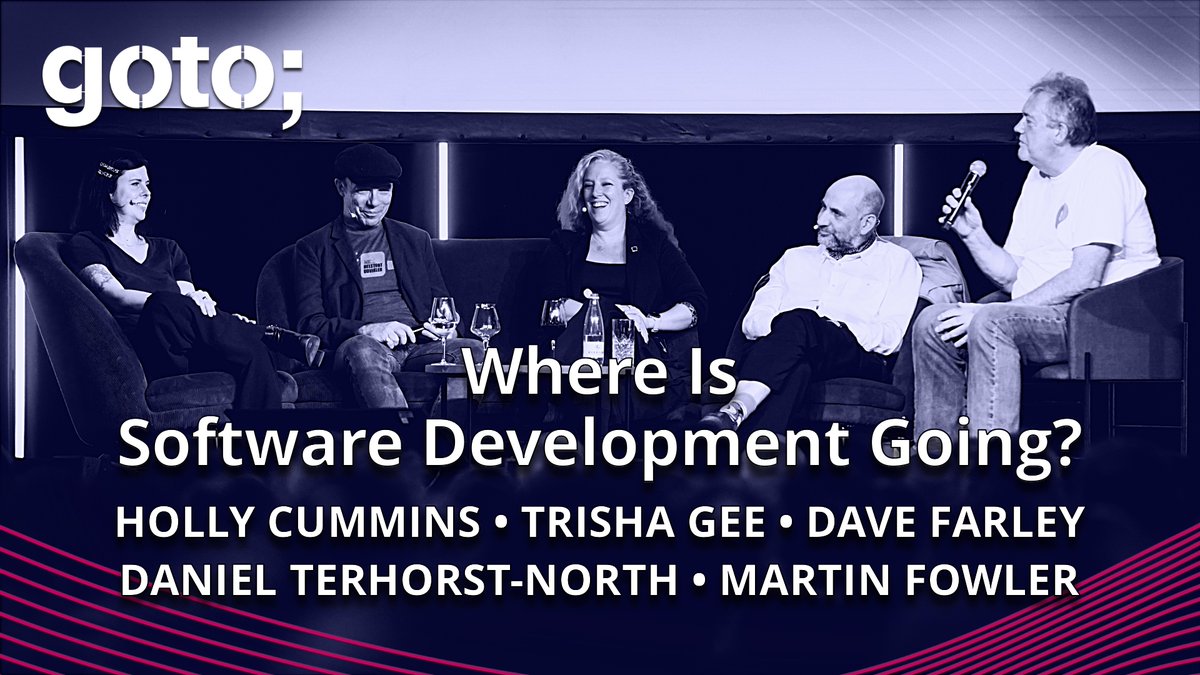

Grier’s Field is the 10-acre, main viewing area for Deerlick members who don’t have homes there, but come to camp in tents, RVs and cars. While there, I met a young man from Peachtree Corners, Georgia, two hours away. He had come to car camp for the night and do some imaging with his telescopes. On the chilly January night, he had the field all to himself. It was hard to tell he was even there after the sun went down, as no light emanated from his campsite (campfires, naturally, are verboten).

The Andromeda Galaxy as seen in a long exposure shot from Deerlick Astronomy Village. Photo: Erik Benner

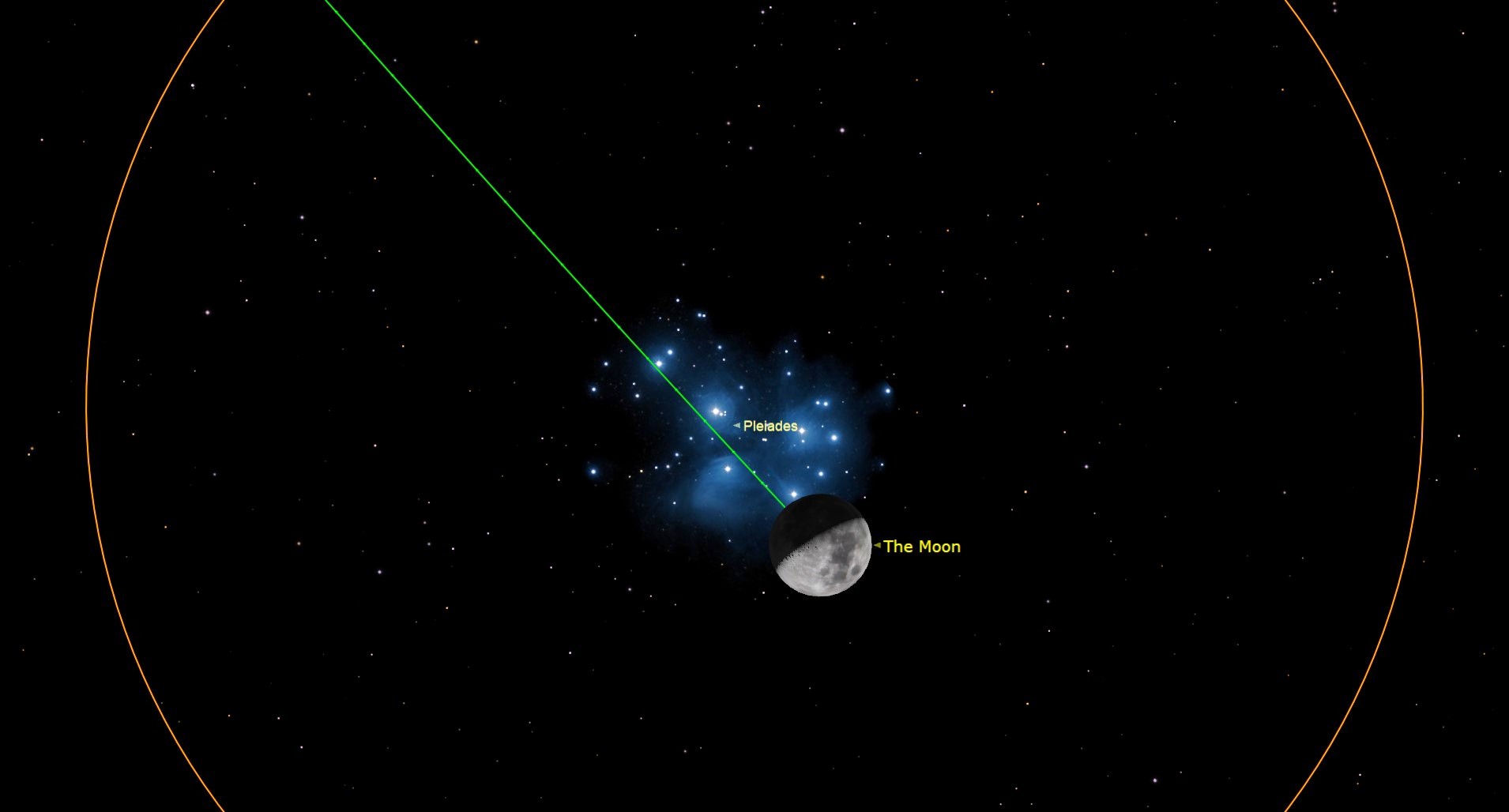

While standing in the middle of the field as twilight turned to darkness, the star show slowly unfolded in a way I never see at home, where I have limited horizon views and the slow creep of light pollution from the Atlanta metro area. Things seemed brighter at Deerlick, like someone had turned the dimmer switch on the heavens to the brightest of illuminations. While there, the International Space Station passed into the field of view among all the planets and constellations. It’s a common occurrence that’s perhaps not a big deal for avid sky watchers, but pretty cool to see for a novice such as myself, especially coming from a suburb.

Grier’s Field has concrete pads for telescopes, bathroom facilities, a picnic pavilion with a gas grill, a small community building (with blackout curtains, of course) that serves as a warming hut on chilly evenings. As Benner pointed out, it also has very good Wi-Fi – something uncommon in such a remote location.

Grier’s Field at Deerlick Astronomy Village. Photo: Blake Guthrie

During the daytime hours, visitors hike on miles of nature trails and spot plenty of wildlife. I was greeted at one point by a large group of deer who let me get within a few feet of them before they darted a few yards away to continue staring intently at me while grazing.

Though Deerlick is a private community, it offers a few public events throughout the year. Event details are available on the Deerlick and Atlanta Astronomy Club event webpages. One of the biggest annual events is the week-long Peach State Star Gaze, held each fall.

However, visitors that want to visit outside of public events can do so. They’ll need to pay the annual membership fee ($60-$85) in advance, plus a nominal nightly camping fee for Grier’s Field ($5-$20). Membership is required, even if you’re only coming for one night.

“It’s cheaper than staying at a KOA,” says Benner. “We do this at cost. We’re not doing it to become independently wealthy.” He recommends that sky-curious novices with no equipment of their own come to one of the public events first, when they can view the stars through telescopes set up for guests, before becoming dues-paying members.

For those interested in becoming members but who aren’t so into camping, the closest lodging are the two-bedroom cottages ($150 per night) about 20 minutes away at A.H. Stephens State Park in Crawfordville, GA. The closest hotel is The Fitzpatrick Hotel ($109 and up) in the town of Washington, a 25-minute drive north of Grier’s Field. Crawfordville and Washington are the closest towns with stores and restaurants, but the options are limited. Crawfordville doesn’t even have a grocery store — only a Dollar General.

Photo: Blake Guthrie

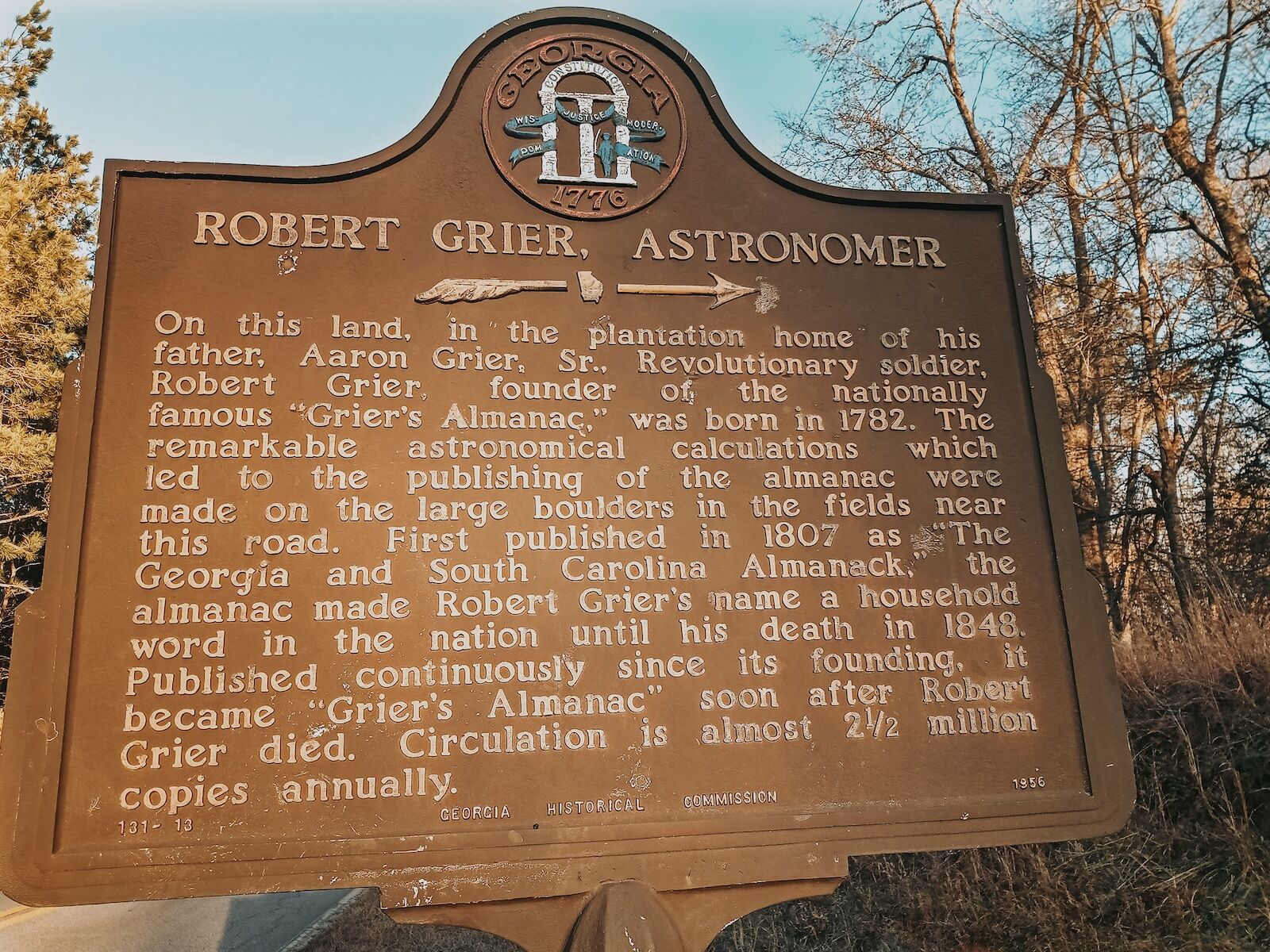

Remote as it is, there’s a lot of history in this area. Within a mile of Deerlick are three roadside historical markers. The lack of people in this area is so evident that when the shoulder was too muddy, I flicked on my hazard lights and parked my car in the middle of the highway to read one of the signs. Not a single vehicle passed as I spent a couple of minutes reading and taking photos of the marker. It tells the story of a pioneering astronomer born there in 1782, even mentioning the specific boulders he stood on to make his astronomical calculations. The man’s name was Robert Grier, and yes, those same boulders are still there on Grier’s Field inside Deerlick Astronomy Village – how apropos.

He’d likely be glad to know that centuries later, this place is still revealing moments of awe to passionate nighttime sky watchers. ![]()