Uranus’ Moon Ariel has Deep Gashes, Could Reveal its Interior

We’ve only gotten one close-up view of Uranus and its moons, and it happened decades ago. In 1986, Voyager 2 performed a flyby of Uranus from about 81,500 km (50,600 mi) of the planet’s cloud tops. It was 130,000 km (80,000 mi) away from Uranus’ moon, Ariel, when it captured the leading image. It showed … Continue reading "Uranus’ Moon Ariel has Deep Gashes, Could Reveal its Interior" The post Uranus’ Moon Ariel has Deep Gashes, Could Reveal its Interior appeared first on Universe Today.

We’ve only gotten one close-up view of Uranus and its moons, and it happened decades ago. In 1986, Voyager 2 performed a flyby of Uranus from about 81,500 km (50,600 mi) of the planet’s cloud tops. It was 130,000 km (80,000 mi) away from Uranus’ moon, Ariel, when it captured the leading image. It showed some unusual features that scientists are still puzzling over.

What do they reveal about the moon’s interior?

Ariel has the usual crater-pitted surface that most Solar System objects display. But its surface also has complex features like ridges, canyons, and steep banks and slopes called scarps. Research published last year suggested that these surface features and chemical deposits are caused by chemical processes inside the moon. Ariel could even have an internal ocean, according to the research.

New research published in The Planetary Science Journal digs deeper into the issue to try and understand what processes could create Ariel’s surface features. Its title is “Ariel’s Medial Grooves: Spreading Centers on a Candidate Ocean World.” The lead author is Chloe Beddingfield from Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL).

“Ariel is a candidate ocean world, and recent observations from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) confirmed that its surface is mantled by a large amount of CO2 ice mixed with lower amounts of CO ice,” Beddingfield and her co-researchers write in their paper. These materials should be unstable on Ariel, though, and should sublimate away into space. “Consequently, the observed constituents on Ariel are likely replenished, possibly from endogenic sources,” the authors write.

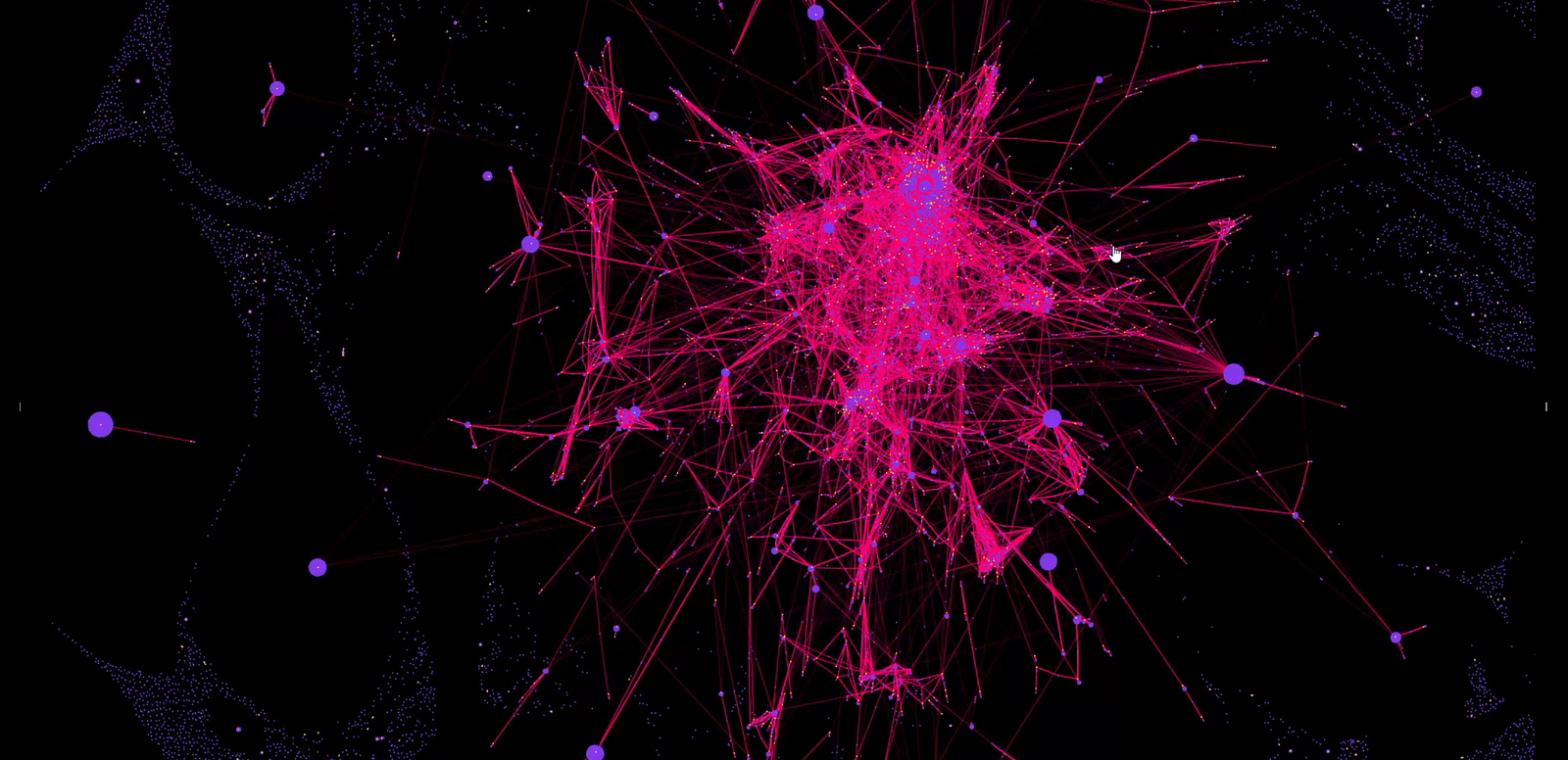

The research is centred on Ariel’s chasma-medial groove systems and how they formed. These are trenches that cut straight through the moon’s huge canyons. While previous research has suggested that the trenches are tectonic fractures, this research arrives at a different hypothesis. “We present evidence that Ariel’s massive chasma-medial groove systems formed via spreading, where internally sourced material ascended and formed new crust,” the paper states.

This is similar to ocean-floor spreading on Earth, which is where new crust forms. If true, it can account for Ariel’s surface deposits of carbon dioxide ice and other carbon-bearing molecules.

“If we’re right, these medial grooves are probably the best candidates for sourcing those carbon oxide deposits and uncovering more details about the moon’s interior,” Beddingfield said in a press release. “No other surface features show evidence of facilitating the movement of materials from inside Ariel, making this finding particularly exciting.”

Ariel’s surface is dominated by three main terrain types: plains, ridged terrain, and cratered terrain. The cratered terrain is the oldest and most extensive type of terrain. The ridged terrain is the second main terrain type and is made of bands of ridges and troughs that can extend for hundreds of kilometres. The plains are the third type and are the youngest of the terrains. They’re on canyon floors and in depressions in the middle of the cratered terrain.

As far as scientists can tell, the grooves that intersect the canyons are the youngest surface features on Ariel. Previous research suggested that they result from the interplay between volcanic and tectonic processes. However, this research says otherwise: spreading could be responsible.

In the 1960s, scientists validated the idea of seafloor spreading on Earth, which led to the acceptance of plate tectonics. One of the main pieces of evidence for plate tectonics is the way the edges of continents like Africa and South America fit together if you “remove” the Atlantic Ocean and the intervening seafloor.

The same thing happened when Beddingfield and her colleagues “removed” the chasm floors on Ariel.

The researchers showed that when they removed the floors of the chasms, the margins lined up. This is strong evidence of spreading. “The margins of Brownie, Kewpie, Korrigan, Pixie, and Sylph Chasmata closely align when the Intermediate Age Smooth Materials (orange unit in Figure 1), which make up the chasma floors, are removed and the Cratered Plains (green unit in Figure 1) are reconstructed,” they write.

According to the research, spreading centers develop above convention cells underneath Ariel’s crust, and heat forces material upward to the crust. The material cools at the surface, forming new crust. The entire process is driven by tidal forces as Ariel orbits the much larger Uranus. This heats the moon’s interior, creating the convection. Some of the moon’s interior cycles between heating as the moon follows its orbit. It’s possible that internal material continuously melts and then refreezes.

“It’s a fascinating situation — how this cycle affects these moons, their evolution and their characteristics,” Beddingfield said.

Like other Solar System moons that experience tidal heating, Ariel may have an ocean under its surface. In a 2024 study, researchers proposed that another of Uranus’ moons, Miranda, could have a subsurface ocean maintained by tidal heating.

However, Beddingfield is skeptical about drawing a connection between Ariel’s grooves and a potential ocean.

“The size of Ariel’s possible ocean and its depth beneath the surface can only be estimated, but it may be too isolated to interact with spreading centers,” she said. “There’s just a lot we don’t know. And while carbon oxide ices are present on Ariel’s surface, it’s still unclear whether they’re associated with the grooves because Voyager 2 didn’t have instruments that could map the distribution of ices.”

The connection between the grooves and the materials deposited on Ariel’s surface is stronger though. “These new results suggest a possible mechanism for emplacing fresh material and short-lived compounds, including carbon monoxide and perhaps ammonia-bearing species on the surface,” said Tom Nordheim, a co-author of this research and the 2024 paper.

“Our results indicate that medial grooves in large chasmata on Ariel are spreading centers, resulting from the exposure of subsurface material, creating new crust,” the authors summarize in their conclusion. “Thus, these features are likely geologic conduits to Ariel’s interior and could be the primary source of CO2, CO, and other volatiles detected on its surface.”

Richard Cartwright from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory led the 2024 study that used the JWST to identify CO ice and CO2 deposits on Ariel. To find more answers about this intriguing moon, Cartwright says we need a dedicated mission to Uranus and its moons. “We need an orbiter that can make close passes of Ariel, map its medial grooves in detail, and analyze their spectral signatures for components like carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide,” he said. “If carbon-bearing molecules are concentrated along these grooves, then it would strongly support the idea that they’re windows into Ariel’s interior.”

The authors agree that only a dedicated mission can provide answers. “The medial grooves are some of the youngest geologic features observed on Ariel, and close flybys of these features by a future Uranus orbiter are imperative to gain insight into recent geologic events and the geologic and geochemical properties of this candidate ocean world,” they write.

There’ve been many proposed missions to Uranus. NASA, the ESA, JAXA, and the CNSA (China National Space Administration) have all had proposals. NASA’s Uranus Orbiter and Probe mission would study Uranus and its moons from orbit by conducting multiple flybys of each major moon. The probe would enter Uranus’ atmosphere. However, even if selected, a plutonium shortage means the mission wouldn’t launch until the mid or late 2030s.

So far, only China has firm plans to send a spacecraft to the ice giant. It will be part of their Tianwen-4 mission to Jupiter and would perform a single flyby of Uranus. The next launch windows for a mission to Uranus are between 2030 and 2034, but China’s mission isn’t scheduled until 2045.

Press Release: New Study Suggests Trench-Like Features on Uranus’ Moon Ariel May Be Windows to Its Interior

Research: Ariel’s Medial Grooves: Spreading Centers on a Candidate Ocean World

The post Uranus’ Moon Ariel has Deep Gashes, Could Reveal its Interior appeared first on Universe Today.

![Marijuana’s hidden threat to fertility and family planning [PODCAST]](https://kevinmd.com/wp-content/uploads/The-Podcast-by-KevinMD-WideScreen-3000-px-1-scaled.jpg)