Every Hunger Games book gets blunter about the messages fans keep missing

Suzanne Collins originally wrote the Hunger Games books because she wanted to explore just war theory. “Just war theory has evolved over thousands of years in an attempt to define what circumstances give you the moral right to wage war and what is acceptable behavior within that war and its aftermath,” she explained in a […]

Suzanne Collins originally wrote the Hunger Games books because she wanted to explore just war theory.

“Just war theory has evolved over thousands of years in an attempt to define what circumstances give you the moral right to wage war and what is acceptable behavior within that war and its aftermath,” she explained in a 10th-anniversary interview. “In The Hunger Games Trilogy, the districts rebel against their own government because of its corruption. The citizens of the districts have no basic human rights, are treated as slave labor, and are subjected to the Hunger Games annually.”

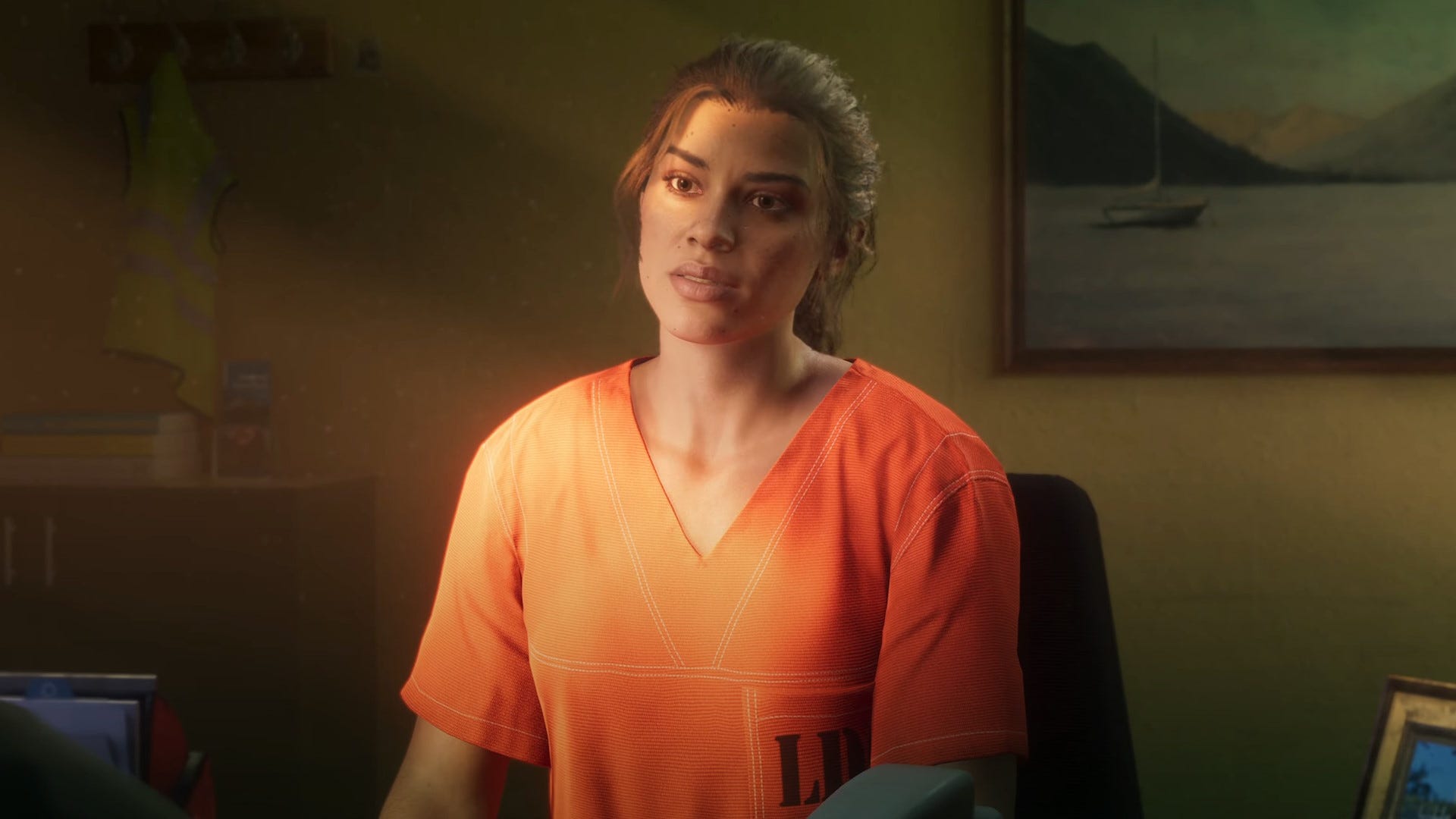

Collins specifically built her world around this concept: In the dystopian country of Panem, the authoritarian Capitol oppresses its 12 outlying Districts to prevent another rebellion like the one that previously tore the country apart. To keep the Districts cowed and also placate the ruling class, the Capitol holds the annual Hunger Games, where 24 District children are forcibly conscripted to fight to the death.

All five books tackle themes of oppression, rebellion, and propaganda. In the first trilogy, protagonist Katniss Everdeen ends up becoming the “spark” that sets off the stewing rebellion. She grapples with what it means to fight in a war and how far she’ll go to keep her family safe. But the response to the books, focused on the gripping, page-turning action, never quite matched up with Collins’ philosophical intentions.

The latest book in the series, Sunrise on the Reaping, is the bluntest Hunger Games book yet — with good reason. With each subsequent Hunger Games book, Collins has stripped away more and more of the spectacle of the Games in order to grab a certain subsection of readers by the scruff of the neck and shake them so they finally get the fucking point. Within the books, Collins continues to pull back the curtain on how the Games work. At this point, though, her changing approach isn’t just so readers can understand the mechanics of war theory and the philosophical questions around rebellion. It’s also a commentary on how the Hunger Games books have been received and warped over time.

The original books weren’t subtle

Ever since the 2008 publication of Collins’ series-launcher The Hunger Games, some of her readers have always ignored the messages about a ruling class using entertainment and propaganda to maintain an oppressive status quo. Instead, they built their fandom around the glamour and drama of the Battle Royale-style fight to the death that gave the book its name, and the drama of its fabricated love triangle — which Collins says she included to represent Katniss’ choice between two different worldviews, not her choice between two different cute boys.

The movie adaptations only emphasized this more superficial response. Though the Hunger Games films are all solid adaptations in their own right, some of the more impactful world-building had to be trimmed in order to translate the story to screen, which means a lot of the power of Collins’ messaging slipped through the cracks. Smaller details like the horrors of the tesserae were vital in coloring the world of the books, but it would have been clunky to tack on exposition like that in a movie.

The movies do add some powerful moments, especially when it comes to scenes outside the perspective of series hero Katniss Everdeen. One of the most chilling movie additions involves rebels in District 5 attacking a hydroelectric dam. The scene is set to a haunting rendition of “The Hanging Tree,” the District 12 folk song turned rallying cry for the rebels across Panem.

But the movies’ official marketing only focused on the glitz and glamour of the Hunger Games. That included selling branded Hunger Games makeup palettes, posting blogs from the point of view of Capitol stylists, and bizarrely, releasing a club remix of “The Hanging Tree.” The movies add some gravitas to make up for the world-building details that didn’t make it into the scripts, but the tone-deaf marketing completely undermined all of it by highlighting the wrong elements of the story. It commoditized the surface-level “fun” of the games — the aspects designed to entertain the Capitol citizens and distract from the sheer horror of making children kill each other. Presenting the world from the Capitol’s viewpoint completely contradicts Collins’ intended message.

The misconstruction of the Hunger Games only got worse when dozens of cheap imitators diluted the message of the original books. These books usually juxtaposed a simplified Chosen One narrative with a grimdark dystopian setting built around some funky concept, like a personality quiz that divided people into social classes based on their single most prominent character trait. The Hunger Games books were so much more than the worst examples of the YA dystopian genre, but many people seemed to forget that.

Suzanne Collins already stripped back the Games

A decade after the last installment of the original trilogy was published, Collins came back with a prequel. 2020’s The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes focuses on young President Snow, the man who would eventually become the dictator of Hunger Games’ dystopian country of Panem. The book shows his gradual escalation into authoritarianism and illustrates how the Games came about in the first place. But in addition to writing a gripping origin story, Collins also held up a pointed looking glass to anyone who was only hooked into her series for the action, spectacle, and YA romance.

The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes returns to the Hunger Games while completely stripping away the “fun” parts of the Games that both Capitol residents and the readers adore — the high-tech arena, the themed costumes, the elaborate training hall, the decadent meals. The tribute children brought to the Capitol for ritual execution in the Hunger Games are caged in the remnants of a zoo, and the arena they’re forced to fight in is just an abandoned amphitheater.

Collins firmly plants readers in the viewpoint of Capitol residents who don’t yet consider the Games an enjoyable, thrilling ceremony — specifically, a group of Academy students tasked with making this horrific, bloody event into something entertaining. So young Corialanus Snow zeroes in on what might captivate a war-weary Capitol audience, offering his ideas to the gamemakers and professors. He introduces sponsorships and betting, and eventually other elements, like sending survivors of the games to big houses in designated Victors’ Villages, in order to further sell the illusion of luxury and comfort to Capitol citizens. His innovations lead Capitol residents to develop rooting interests and one-sided parasocial relationships with their favorite Victors.

Songbirds and Snakes feels like Collins asking her readership to reflect on why we latched on to the “fun” elements of the Games in the first place. She wants us to realize we’re no better than the Capitol citizens if we coo over the gorgeous dresses and thrill to the horrors waiting for the tributes in the arena. Those displays were specifically designed to be incredibly entertaining in order to distract from the sheer cruelty of the Games themselves. It’s telling that those showy trappings were so distracting to fans of the books as well.

Naturally, people missed the point. There were some reviews that said Collins included too much death in her books, or that she should stick to “plucky heroes,” as if surly, recalcitrant, and deeply traumatized Katniss Everdeen in the original trilogy could be described as “plucky.”

When Songbirds and Snakes got its own screen adaptation, the movie’s marketing once again focused on the most surface-level interpretation of the story. In this case, since the glitzy parts of the Games weren’t fully formed yet, the marketing was all about being an Academy student. Text message campaigns reminded fans about the Academy dress code and invited them to dine at the welcome dinner. An official Roblox game let fans play the role of an Academy student with the goal of simply collecting items to graduate.

The genre of “special school in a fictional world” certainly has a proven audience appeal, be it Xavier’s School for Gifted Youngsters in the X-Men franchise or Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry in the world of Harry Potter. In the case of Songbirds and Snakes, Collins used the students’ perspective to explore the reasoning behind why each of the more entertaining Game mechanics, like sponsors and betting, were added. But divorced from that context, the online shop dedicated to Academy merchandise feels like the marketing team tried to cram the series into a familiar angle that people already knew and loved.

And as with the rampant “Team Peeta vs. Team Gale” discussions of the past, some readers decided the most important takeaway from the book was the doomed love story between Snow and Lucy Gray, the Covey girl he’s supposed to mentor through the Hunger Games, and who he initially sees as a route to his own political success.

This time, she’s not playing

With Sunrise on the Reaping, Collins had yet another chance to strip away the trappings of the Games and get readers to finally see the more intellectual messaging she was trying to get her readers considering and discussing. In an interview with her longtime editor David Levithan, Collins said Sunrise on the Reaping is about resisting “implicit submission,” and unpacking which elements of a society are innate and inevitable versus which can be fought against and changed. She said she’d consider the book a win if all people do in response is discuss one specific quote from Scottish philosopher David Hume that fascinates her:

“Nothing appears more surprising to those, who consider human affairs with a philosophical eye, than the easiness with which the many are governed by the few; and the implicit submission, with which men resign their own sentiments and passions to those of their rulers.”

This time, she’s making her philosophical inquiries even more overt. The entire book is about media manipulation, particularly how authoritarian governments twist events in order to create a specific narrative. Within the Hunger Games universe, it’s another reminder that the history Katniss originally believed to be true was carefully crafted by the Capitol. For 74 years, she was told, the Districts fell in line and obediently let the Hunger Games happen. But even Katniss isn’t immune to Capitol propaganda. In the second book, she sits down with Peeta to watch the Hunger Games that her mentor Haymitch won when he was a teenager, and she doesn’t question the events that play out on the official Capitol broadcast.

As it turns out, though, the real story is more complicated. Haymitch is actually part of a small rebel movement. He’s well aware that the Capitol is using him for their ruthless agenda of subduing the Districts and placating the masses, but he wants to control the narrative as much as he can. He doesn’t want the Capitol to profit off his image, but he does want to win over sponsors so he can survive in the Games long enough to carry out a planned sabotage. While trying to survive before and during the Games, he periodically stops to consider just how he’s coming off to the viewing public, what he’s trying to say to them instead, and what he can try to say, given the constraints of trying to keep his collaborators safe and hide his true intentions.

But in the end, it’s all for naught. The Capitol picks and chooses the parts of his story they want the public to see. They paint him as an edgy lone wolf with little regard for his allies, instead of an altruistic rebel who risked his life time and time again to save others, particularly those who couldn’t save themselves. Anything related to the rebel plans is completely wiped from the official broadcast.

It’s a blatant example of how easily the media can manipulate narratives, particularly in the hands of an unscrupulous regime. But it also feels like Collins is commenting on people who pick and choose which parts of her stories they want to see. Those who read the Hunger Games books and watch the movies only for the grisly deaths, the glamorous parades, and the swoonworthy love triangle end up ignoring what Collins is actually trying to communicate about war theory. Latch on to Snow and Lucy Gray’s tragic romance, and you’re completely disregarding how his controlling, manipulative obsession with her fueled his descent into ruthless tyranny.

These books aren’t subtle, but that’s the point, considering how easily readers and Hollywood alike ignored Collins’ intentions and her messages about oppression and authoritarianism. Sunrise on the Reaping isn’t just a primer on media manipulation; it’s Collins confronting a certain type of Hunger Games fan head-on, asking them exactly why they’re editing out her stories’ most uncomfortable themes and what they hope to achieve by softening the overall message to cater to their own palates.

It’s easy to get swept up in the spectacle of the Hunger Games. But that would be disregarding everything Collins has been shouting from the very beginning. She’s been blatant about her intentions, openly talking about the philosophies and theories behind her work. But this time, she’s marching right into the room to make her point.