Confucius Shrine in Nagasaki in Nagasaki, Japan

For a period of several centuries, Nagasaki was the only gateway to the outside world within feudal Japan. While European missionaries and traders only arrived in 1543, Chinese people from various backgrounds had been visiting Japan for a far longer period, and had established settlements throughout Kyushu island. After Sakoku isolationist policies enforced by the Shogunate restricted contact with the outside world to only Chinese, Portuguese, and Dutch traders in Nagasaki, specialized areas were built to separately house each of these groups. At first, the Chinese settlers were restricted to an island in the harbor for business and another area slightly inland to live in. In close proximity to traditional Japanese residential neighborhoods, the Chinese settlers began building rich and vividly colored temples that remain today designated as National Treasures or important historic properties, such as Sofuku-ji nd Kofuku-ji. While these temples are unique themselves, with Chinese architecture, vivid red painted halls, and shrines to Mazu, the Chinese folk goddess of the sea, there was still no place for Chinese settlers belonging to other common religions of the time to pray. After the events of the mid-19th century brought about the end of Sakoku policies as well as rapid modernization and industrialization, Nagasaki yet again had a big part to play. Rich and well-known due to centuries of foreign trade, Western powers had already been establishing a permanent presence in the Oura district of Nagasaki. Churches, synagogues, hotels, residences, and consulates were built in unmistakably western styles of brick and wood with Japanese design features in their tiled roofs, a fairly standard Meiji period architecture style that fused East and West. In 1893, Chinese settlers, who were by this time also living close to this area, built this Nagasaki "Kōshi-byō" Confucius shrine. The ornate and rich design of the buildings within are at odds with the more simply decorated Japanese temples and shrines in the area, and the bright red and orange adds to an already exotic and cosmopolitan atmosphere in Nagasaki. Despite the building's exterior being damaged in the nuclear bombing of the city in 1945, the area was thankfully far enough away to protect from fires and total destruction. Today, the shrine is host to several lively events throughout the year that still bear a strong Chinese influence, including dragon dances and other festivities during the Chinese New Year celebrations (which coincides with the Nagasaki city-wide lantern festival). Another unique point is that the shrine and its land are still property of the Chinese Embassy to Japan, and by extension belong to the Chinese government. A museum was built in 1983 that houses a large collection of ancient Chinese treasures and illustrates the historical relationship between Nagasaki and China throughout the ages.

For a period of several centuries, Nagasaki was the only gateway to the outside world within feudal Japan. While European missionaries and traders only arrived in 1543, Chinese people from various backgrounds had been visiting Japan for a far longer period, and had established settlements throughout Kyushu island. After Sakoku isolationist policies enforced by the Shogunate restricted contact with the outside world to only Chinese, Portuguese, and Dutch traders in Nagasaki, specialized areas were built to separately house each of these groups.

At first, the Chinese settlers were restricted to an island in the harbor for business and another area slightly inland to live in. In close proximity to traditional Japanese residential neighborhoods, the Chinese settlers began building rich and vividly colored temples that remain today designated as National Treasures or important historic properties, such as Sofuku-ji nd Kofuku-ji. While these temples are unique themselves, with Chinese architecture, vivid red painted halls, and shrines to Mazu, the Chinese folk goddess of the sea, there was still no place for Chinese settlers belonging to other common religions of the time to pray.

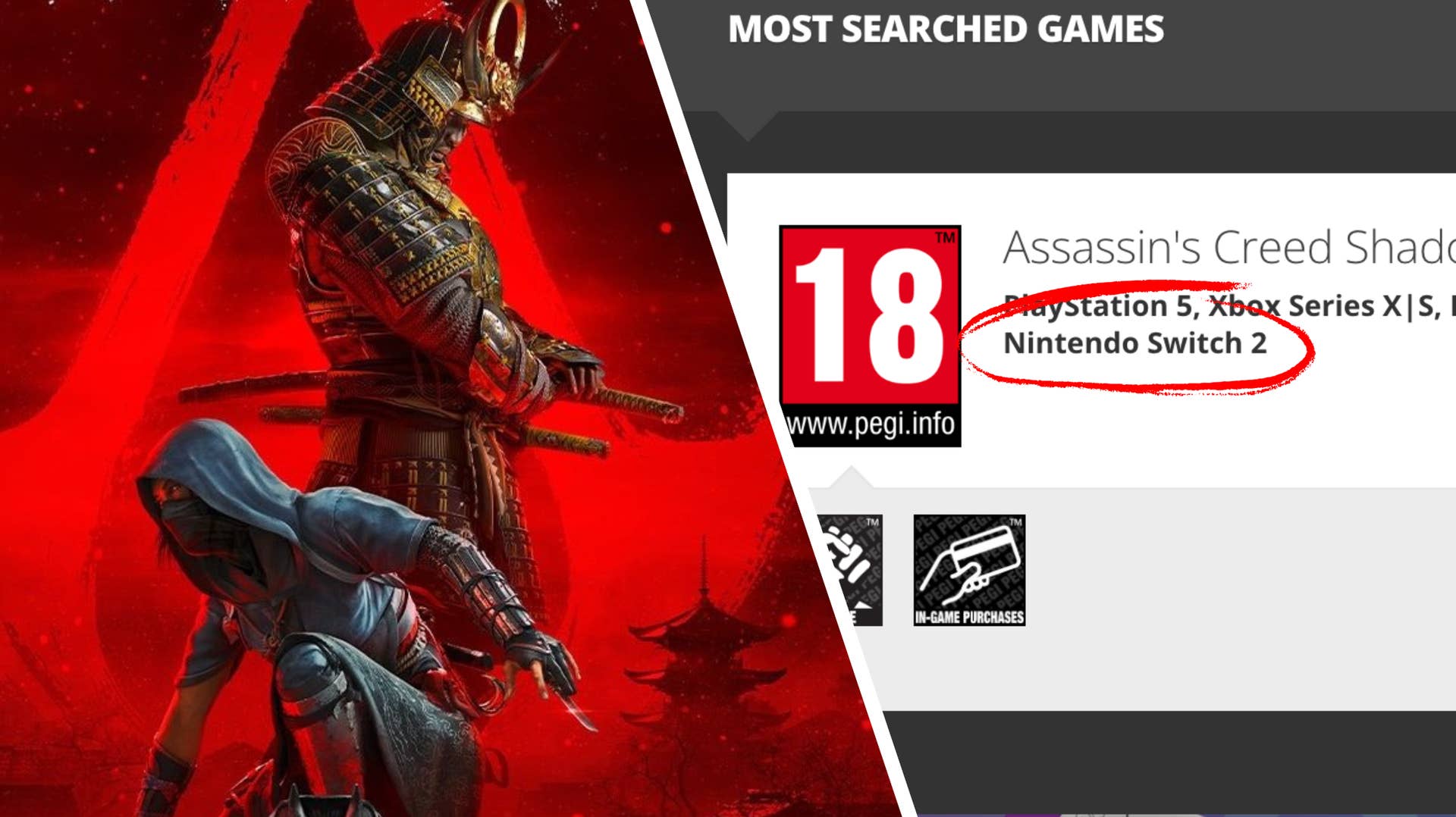

After the events of the mid-19th century brought about the end of Sakoku policies as well as rapid modernization and industrialization, Nagasaki yet again had a big part to play. Rich and well-known due to centuries of foreign trade, Western powers had already been establishing a permanent presence in the Oura district of Nagasaki. Churches, synagogues, hotels, residences, and consulates were built in unmistakably western styles of brick and wood with Japanese design features in their tiled roofs, a fairly standard Meiji period architecture style that fused East and West. In 1893, Chinese settlers, who were by this time also living close to this area, built this Nagasaki "Kōshi-byō" Confucius shrine.

The ornate and rich design of the buildings within are at odds with the more simply decorated Japanese temples and shrines in the area, and the bright red and orange adds to an already exotic and cosmopolitan atmosphere in Nagasaki. Despite the building's exterior being damaged in the nuclear bombing of the city in 1945, the area was thankfully far enough away to protect from fires and total destruction.

Today, the shrine is host to several lively events throughout the year that still bear a strong Chinese influence, including dragon dances and other festivities during the Chinese New Year celebrations (which coincides with the Nagasaki city-wide lantern festival).

Another unique point is that the shrine and its land are still property of the Chinese Embassy to Japan, and by extension belong to the Chinese government. A museum was built in 1983 that houses a large collection of ancient Chinese treasures and illustrates the historical relationship between Nagasaki and China throughout the ages.