Castleguard Cave in Canada

Castleguard Cave is rife with superlatives. It’s the longest cave system in Canada at 13 miles (21 kilometers), as well as the only non-ice cave that sits beneath a current glacier, called the Columbia Icefield, which is the largest ice mass left in the Rocky Mountains. The result is a grand subterranean world that combines both cave and glacier attributes in a combo hardly seen before. In addition to calcium stalactites, stalagmites, and long soda straws, the cave also hosts extremely rare cave pearls, which are like spheres of calcium salt. Access to the cave requires a permit from the national park, as it’s quite dangerous. Teams are only able to do so in winter, when the cave is less likely to flood and a pool of water near the entrance freezes thick enough to be able to cross. After reaching the cave entrance in the meadow of a valley, cavers drop down a 26-foot shaft, then belly-crawl over the ice pond to reach a pool of water in the warmer interior of the cave. Scuba diving is then required to get any further, to a tunnel that is so perfectly round it’s referred to as “The Subway.” The only known paths burrow deep below Castleguard Mountain until they finally terminate at the glacier itself, completely blocked by the ice that’s around 650 to 1,000-feet thick. That means there’s only way in and out of the 13-mile cavern, making it the world’s furthest exit in a cave, so quick rescues are not an option. In the summer months, glacier melt floods the cave, pouring rapidly down a shaft called “Boon’s Blunder” and out the only entrance. A few areas of the cave are named after Mike Boon, an intrepid caver. But because Boon explored Castleguard in 1970 without permission of Parks Canada, officials did not allow details of his journey to be published, so little is publicly known about his mysterious descent and whatever “blunder” happened to earn the flooding shaft its name. Research teams have discovered a few animals that depend on this cold, dark environment, including some small pack rats and two blind, translucent shrimp creatures. One of those crustaceans, called Castleguard Cave Amphipod (Stygobromus canadensis), is found nowhere else in the world. Scientists speculate that this animal survived the ice age by sheltering in this cave. It’s a place that is still being explored by researchers and spelunkers looking to put their name on potentially new expansions yet to be discovered.

Castleguard Cave is rife with superlatives. It’s the longest cave system in Canada at 13 miles (21 kilometers), as well as the only non-ice cave that sits beneath a current glacier, called the Columbia Icefield, which is the largest ice mass left in the Rocky Mountains. The result is a grand subterranean world that combines both cave and glacier attributes in a combo hardly seen before. In addition to calcium stalactites, stalagmites, and long soda straws, the cave also hosts extremely rare cave pearls, which are like spheres of calcium salt.

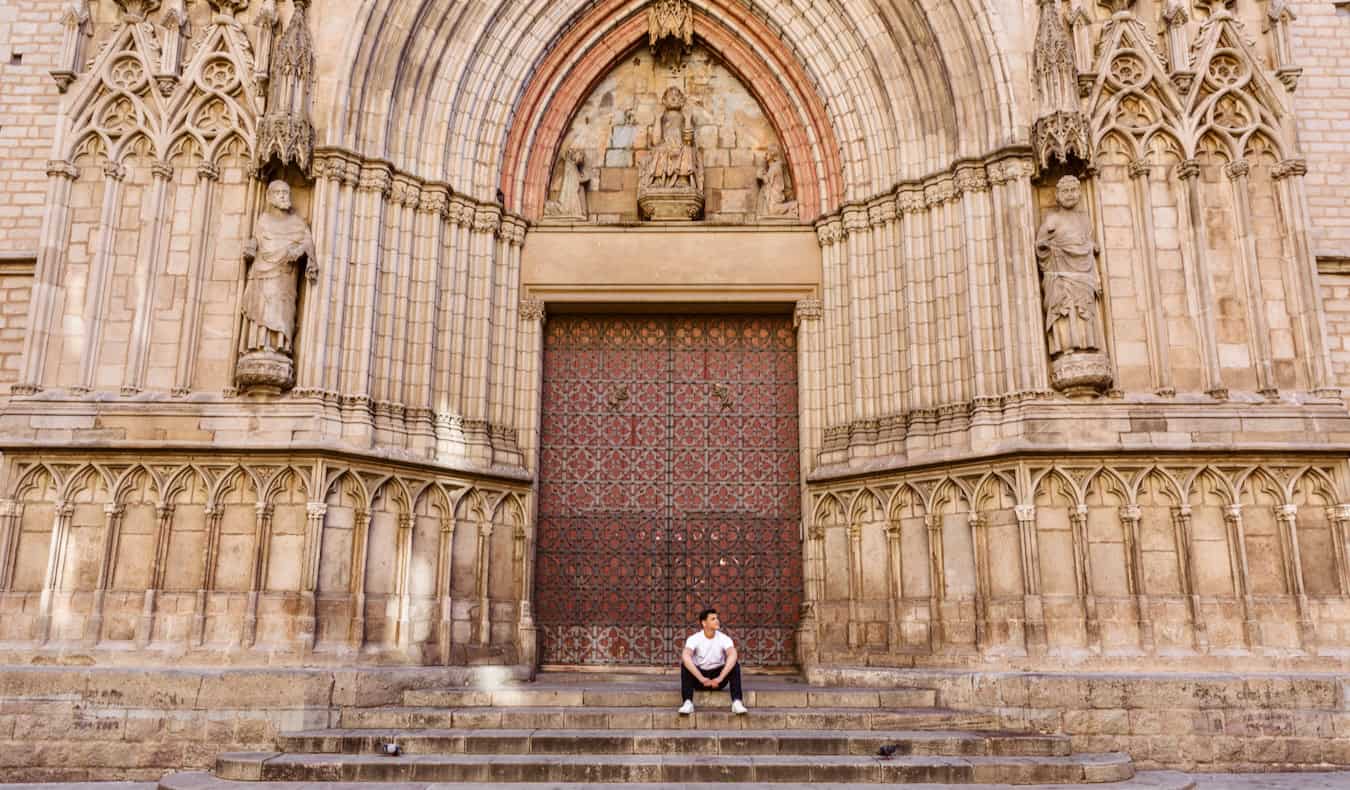

Access to the cave requires a permit from the national park, as it’s quite dangerous. Teams are only able to do so in winter, when the cave is less likely to flood and a pool of water near the entrance freezes thick enough to be able to cross. After reaching the cave entrance in the meadow of a valley, cavers drop down a 26-foot shaft, then belly-crawl over the ice pond to reach a pool of water in the warmer interior of the cave.

Scuba diving is then required to get any further, to a tunnel that is so perfectly round it’s referred to as “The Subway.” The only known paths burrow deep below Castleguard Mountain until they finally terminate at the glacier itself, completely blocked by the ice that’s around 650 to 1,000-feet thick. That means there’s only way in and out of the 13-mile cavern, making it the world’s furthest exit in a cave, so quick rescues are not an option. In the summer months, glacier melt floods the cave, pouring rapidly down a shaft called “Boon’s Blunder” and out the only entrance.

A few areas of the cave are named after Mike Boon, an intrepid caver. But because Boon explored Castleguard in 1970 without permission of Parks Canada, officials did not allow details of his journey to be published, so little is publicly known about his mysterious descent and whatever “blunder” happened to earn the flooding shaft its name.

Research teams have discovered a few animals that depend on this cold, dark environment, including some small pack rats and two blind, translucent shrimp creatures. One of those crustaceans, called Castleguard Cave Amphipod (Stygobromus canadensis), is found nowhere else in the world. Scientists speculate that this animal survived the ice age by sheltering in this cave. It’s a place that is still being explored by researchers and spelunkers looking to put their name on potentially new expansions yet to be discovered.