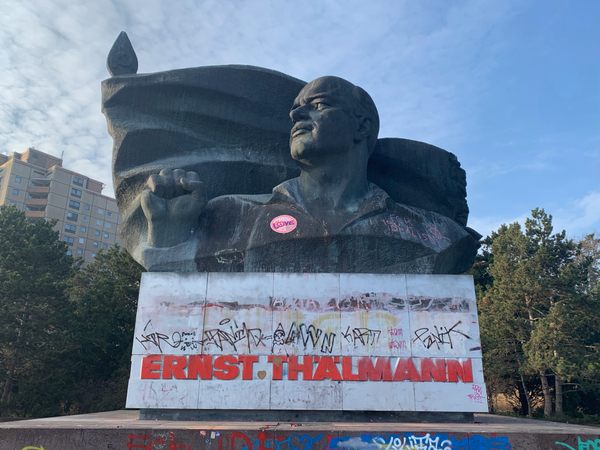

Statue of the Prophet Daniel on the Metz Cathedral in Metz, France

This statue on the Metz Cathedral has a story that reflects the town’s tumultuous political history. It forms part of the grand, gothic West Portal, which is covered in dozens of statues of saints, prophets, and angels. At first glance, it looks—like the rest of the cathedral—to date from the High Middle Ages. But the portal was actually built in 1903, during the period that Metz was part of the German Empire. The original medieval doorway had been destroyed in the 1750s (when Metz was French) by Renaissance architects who thought Gothic art was backwards and barbaric, and who replaced it with a more fashionable Neo-Classical facade. By the late 19th century, tastes had changed. The leading artists were now Romantics who idealized medieval Europe as a time of chivalry and piety. A Franco-German duo, Paul Tornow and Auguste Dujardin, were sponsored by the German Emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, to restore Metz Cathedral to its former Gothic glory. They traveled around France photographing medieval art as references for the statues they made for the West Portal, to make them as accurate to the period as possible. As a nod to their patron, they gave the figure of the biblical prophet Daniel the very un-Medieval likeness of the Kaiser, including his distinctive upturned waxed mustache (which was at that time copied, with mixed success, by lots of German men). But unlike Daniel, a wise and diplomatic man, Wilhelm II was arrogant and tactless. And while, domestically, his Empire flourished, it was ruined in World War I. He was deposed, and Metz re-annexed by France. The people of Metz handcuffed the Kaiser-Daniel statue and painted on his scroll the words “Sic transit Gloria Mundi” (“So passes the glory of the world”). Two decades later, war had broken out again. Instability in Germany had given rise to the Nazis, who rolled into Metz in 1940 and brought Hitler there to celebrate Christmas. They shelled the cathedral, and expelled 100 Catholic priests and 3,000 Jews from the region. They also took exceptional offense that the statue of Daniel—an Old Testament, and therefore Jewish, figure—had been given the face of a German Kaiser. A sculptor was hired to chisel off the distinctive mustache and to “de-Aryanize” his features. Thus he still stands— now French again—clean-shaven and solemn, pointing in warning at a blank scroll.

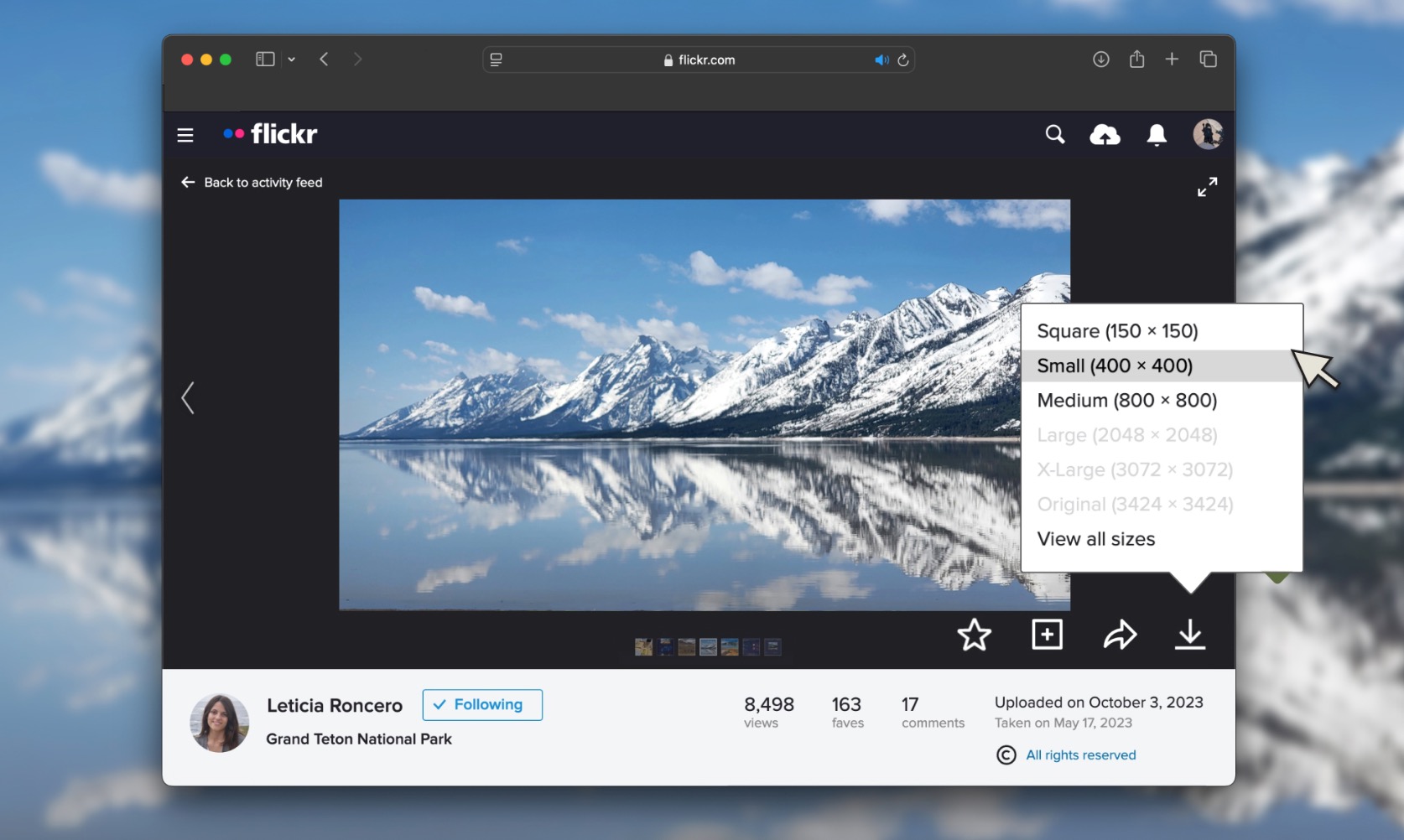

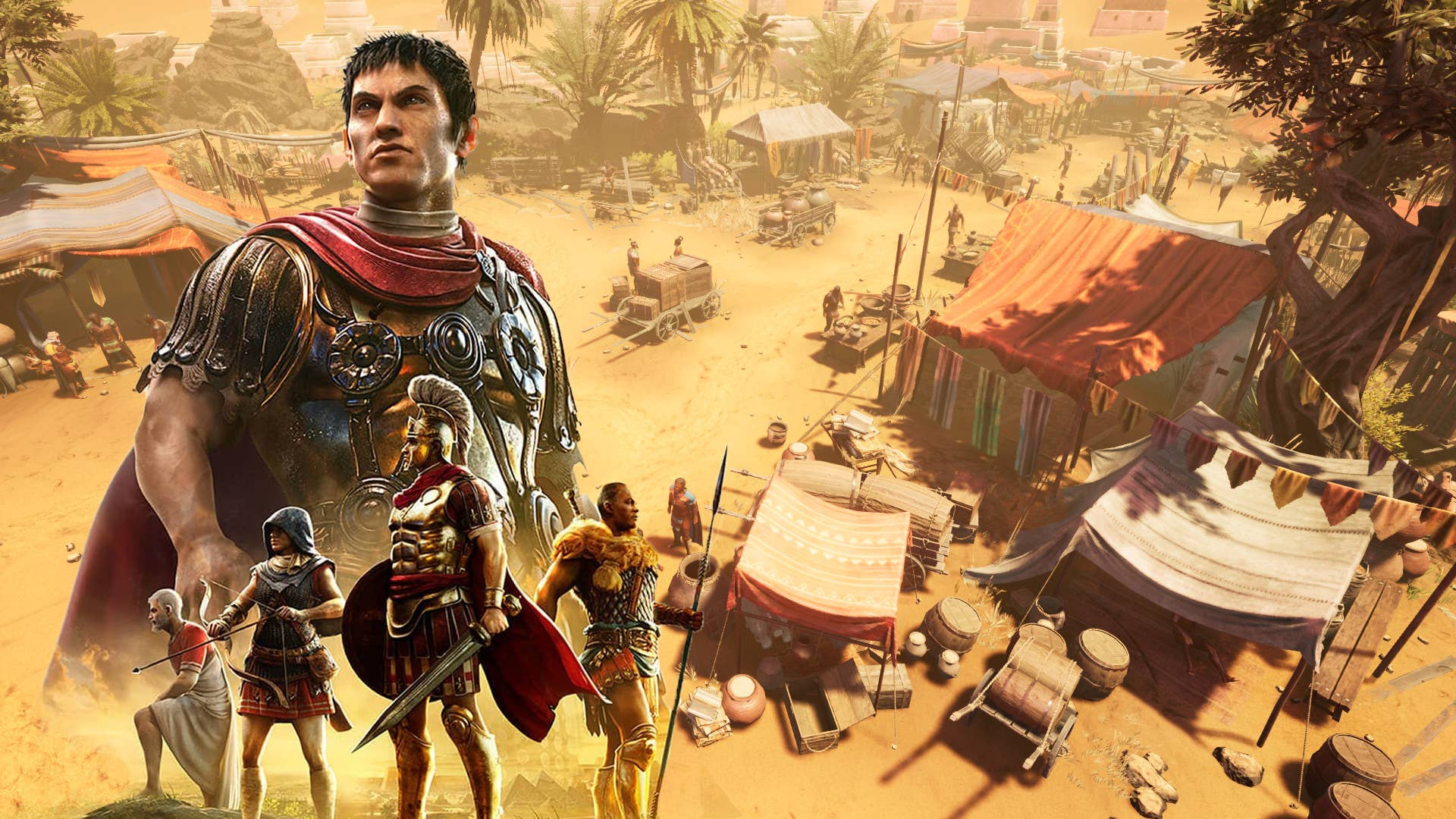

This statue on the Metz Cathedral has a story that reflects the town’s tumultuous political history. It forms part of the grand, gothic West Portal, which is covered in dozens of statues of saints, prophets, and angels. At first glance, it looks—like the rest of the cathedral—to date from the High Middle Ages. But the portal was actually built in 1903, during the period that Metz was part of the German Empire. The original medieval doorway had been destroyed in the 1750s (when Metz was French) by Renaissance architects who thought Gothic art was backwards and barbaric, and who replaced it with a more fashionable Neo-Classical facade.

By the late 19th century, tastes had changed. The leading artists were now Romantics who idealized medieval Europe as a time of chivalry and piety. A Franco-German duo, Paul Tornow and Auguste Dujardin, were sponsored by the German Emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, to restore Metz Cathedral to its former Gothic glory. They traveled around France photographing medieval art as references for the statues they made for the West Portal, to make them as accurate to the period as possible. As a nod to their patron, they gave the figure of the biblical prophet Daniel the very un-Medieval likeness of the Kaiser, including his distinctive upturned waxed mustache (which was at that time copied, with mixed success, by lots of German men). But unlike Daniel, a wise and diplomatic man, Wilhelm II was arrogant and tactless. And while, domestically, his Empire flourished, it was ruined in World War I.

He was deposed, and Metz re-annexed by France. The people of Metz handcuffed the Kaiser-Daniel statue and painted on his scroll the words “Sic transit Gloria Mundi” (“So passes the glory of the world”).

Two decades later, war had broken out again. Instability in Germany had given rise to the Nazis, who rolled into Metz in 1940 and brought Hitler there to celebrate Christmas. They shelled the cathedral, and expelled 100 Catholic priests and 3,000 Jews from the region. They also took exceptional offense that the statue of Daniel—an Old Testament, and therefore Jewish, figure—had been given the face of a German Kaiser.

A sculptor was hired to chisel off the distinctive mustache and to “de-Aryanize” his features. Thus he still stands— now French again—clean-shaven and solemn, pointing in warning at a blank scroll.