The Berbice Rebellion of 1763 Ended With a Letter

Listen and subscribe on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. Dylan: Hey, Baudelaire, how you doing? What’s going on? Baudelaire: I am doing great, Dylan. How are you doing? Dylan: I’m good. So you are coming back again with, looks like, another story about the Caribbean. Baudelaire: Yes. Yes. And this time, we’re talking about a massive rebellion. This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. Dylan: I feel like this is actually not the first time. I feel like massive rebellions in the Caribbean, whatever that venn diagram—this is like a solid Baudelaire story zone. Baudelaire: Yeah, I’m Haitian, so, you know, I’m all about it. Dylan: Exactly. All right, but this is not a Haitian story. This is a different rebellion story. Where are we today? Baudelaire: We are in the nation of Guyana. You see, today in their capital, they have a statue of their first hero. It’s called the 1763 Monument. Let’s look at the picture together real quick. I’ll send you a link. Dylan: Okay, who—it kind of looks like the proportions of the character are strange. They kind of almost look like child. Who is this a statue of? Baudelaire: This is Cuffy. He was the leader of the Berbice Rebellion of 1763. Throughout the statue, you have bases of Guyanese heroes post-Cuffy etched into the statue. You have a map of Guyana on Cuffy’s back. You have odes to Africa throughout the statue. Dylan: Okay. And this is a statue in his honor? Like, why is there a statue to him? Baudelaire: Well, the statue is in honor of the rebellion, which Cuffy was the leader of. The rebellion that happened 12 years before the American Revolution and 28 years before the Haitian Revolution. We’re talking thousands of formerly enslaved Africans who had their former captors and the governor of the colony on the run. And they had full control of the colony for 10 months. And if it weren’t for one act of civility, probably would have won their freedom. Dylan: One act of civility is very curious. Like someone held the door open for the wrong person. All right, let’s go. Let’s get into it. My name is Baudelaire, and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Today, we journey to South America, to the lush landscapes of Guyana, where a 15-foot bronze statue stands tall in Georgetown Square of the Revolution. This is the story of Cuffy and his army, who came closer than ever before to overthrowing slavery, and to reclaiming their land. Today, we’re going to explore the history of Cuffy and his army, who came closer than ever before to overthrowing slavery, and establishing their own state. Dylan: All right, so this story takes place in Guyana. That’s by Venezuela, the Northern Eastern edge of South America, yeah? Baudelaire: Yeah. But in the mid-1700s, what is today Guyana was a Dutch colony called Berbice. Dylan: So what’s going on in Berbice? Baudelaire: Okay, so the mid-1700s in Berbice were pretty intense. Like other colonies throughout the Caribbean, it was a slave-based economy, really built on the trade of sugar and coffee. But at this time, the Seven Years’ War just popped off between England and France. Because of that war, trade routes and supply chains were all over the place. You also got tropical diseases that went around, like malaria and yellow fever. Dylan: This feels very 1700s, like I’m going to get exploded by cannons or die of yellow fever. So this is all kind of the context for this rebellion. What is Cuffy doing in Guyana? What else is going on there? Baudelaire: Well, the thing about Berbice that creates a situation right for what happens is the Africans drastically outnumber the Dutch population. There’s about 4,000 to 5,000 enslaved people compared to just 340, 350 whites. With Africans outnumbering the Dutch so much, the Dutch are relying more and more on brutality to keep that African population in line, right? They’re paranoid. Dylan: They’re afraid because they know that they’re outnumbered 10 to one. They don’t really have a shot in a serious rebellion. Baudelaire: Exactly. So in all this, Cuffy is enslaved on the Lilienberg Plantation as a house slave. Even though he has the highest position that an enslaved person could have, he still ultimately wanted liberation and freedom. On February 23rd, 1763, it officially kicks off. Dylan: How does that, what does that look like? Baudelaire: Well, the rebellion didn’t begin at Cuffy’s plantation, but a nearby one. Seventy-five Africans killed their master and overseer. And so after that, it kind of became a situation where it was almost like a domino effect, where then they’re traveling from plantation to plantation and their forces are growing rapidly. Dylan: And this is kind of the thing that the Dutch had been afraid of becaus

Listen and subscribe on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Dylan: Hey, Baudelaire, how you doing? What’s going on?

Baudelaire: I am doing great, Dylan. How are you doing?

Dylan: I’m good. So you are coming back again with, looks like, another story about the Caribbean.

Baudelaire: Yes. Yes. And this time, we’re talking about a massive rebellion.

This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Dylan: I feel like this is actually not the first time. I feel like massive rebellions in the Caribbean, whatever that venn diagram—this is like a solid Baudelaire story zone.

Baudelaire: Yeah, I’m Haitian, so, you know, I’m all about it.

Dylan: Exactly. All right, but this is not a Haitian story. This is a different rebellion story. Where are we today?

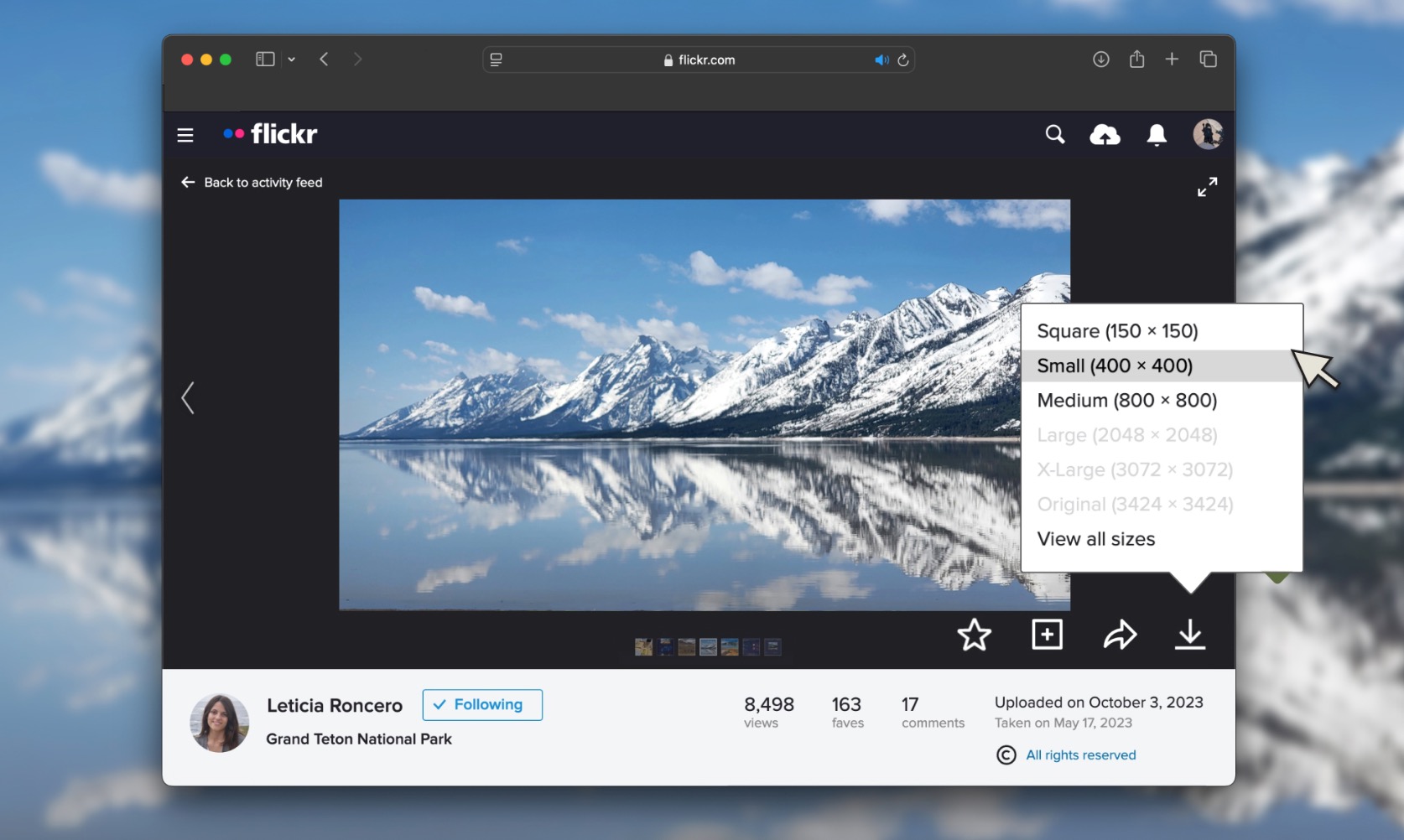

Baudelaire: We are in the nation of Guyana. You see, today in their capital, they have a statue of their first hero. It’s called the 1763 Monument. Let’s look at the picture together real quick. I’ll send you a link.

Dylan: Okay, who—it kind of looks like the proportions of the character are strange. They kind of almost look like child. Who is this a statue of?

Baudelaire: This is Cuffy. He was the leader of the Berbice Rebellion of 1763. Throughout the statue, you have bases of Guyanese heroes post-Cuffy etched into the statue. You have a map of Guyana on Cuffy’s back. You have odes to Africa throughout the statue.

Dylan: Okay. And this is a statue in his honor? Like, why is there a statue to him?

Baudelaire: Well, the statue is in honor of the rebellion, which Cuffy was the leader of. The rebellion that happened 12 years before the American Revolution and 28 years before the Haitian Revolution. We’re talking thousands of formerly enslaved Africans who had their former captors and the governor of the colony on the run. And they had full control of the colony for 10 months. And if it weren’t for one act of civility, probably would have won their freedom.

Dylan: One act of civility is very curious. Like someone held the door open for the wrong person. All right, let’s go. Let’s get into it.

My name is Baudelaire, and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Today, we journey to South America, to the lush landscapes of Guyana, where a 15-foot bronze statue stands tall in Georgetown Square of the Revolution. This is the story of Cuffy and his army, who came closer than ever before to overthrowing slavery, and to reclaiming their land. Today, we’re going to explore the history of Cuffy and his army, who came closer than ever before to overthrowing slavery, and establishing their own state.

Dylan: All right, so this story takes place in Guyana. That’s by Venezuela, the Northern Eastern edge of South America, yeah?

Baudelaire: Yeah. But in the mid-1700s, what is today Guyana was a Dutch colony called Berbice.

Dylan: So what’s going on in Berbice?

Baudelaire: Okay, so the mid-1700s in Berbice were pretty intense. Like other colonies throughout the Caribbean, it was a slave-based economy, really built on the trade of sugar and coffee. But at this time, the Seven Years’ War just popped off between England and France. Because of that war, trade routes and supply chains were all over the place. You also got tropical diseases that went around, like malaria and yellow fever.

Dylan: This feels very 1700s, like I’m going to get exploded by cannons or die of yellow fever. So this is all kind of the context for this rebellion. What is Cuffy doing in Guyana? What else is going on there?

Baudelaire: Well, the thing about Berbice that creates a situation right for what happens is the Africans drastically outnumber the Dutch population. There’s about 4,000 to 5,000 enslaved people compared to just 340, 350 whites. With Africans outnumbering the Dutch so much, the Dutch are relying more and more on brutality to keep that African population in line, right? They’re paranoid.

Dylan: They’re afraid because they know that they’re outnumbered 10 to one. They don’t really have a shot in a serious rebellion.

Baudelaire: Exactly. So in all this, Cuffy is enslaved on the Lilienberg Plantation as a house slave. Even though he has the highest position that an enslaved person could have, he still ultimately wanted liberation and freedom. On February 23rd, 1763, it officially kicks off.

Dylan: How does that, what does that look like?

Baudelaire: Well, the rebellion didn’t begin at Cuffy’s plantation, but a nearby one. Seventy-five Africans killed their master and overseer. And so after that, it kind of became a situation where it was almost like a domino effect, where then they’re traveling from plantation to plantation and their forces are growing rapidly.

Dylan: And this is kind of the thing that the Dutch had been afraid of because now they are outnumbered. And it sounds like Cuffy sort of ends up leading this rebellion. How did the Dutch respond to this?

Baudelaire: So the governor of the colony is a Dutch man by the name of Wolfert Simon van Hoogenheim.

Dylan: That’s a Dutch name. Van Hoogenheim—that’s pretty Dutch.

Baudelaire: Yeah. Van Hoogenheim, like the rest of the Dutch in the colony, he kind of was already in like semi-panic mode. This is barely a month into the rebellion. He goes and he rounds up all the military men that he can find, which ends up being 12 sailors and 12 soldiers.

Dylan: That is not gonna do it.

Baudelaire: No, no.

Dylan: You are toast, my guy. You are dead. That’s not gonna work.

Baudelaire: No, not at all. So while van Hoogenheim is getting his couple dozen men together, Cuffy’s troops are still going plantation to plantation over the coming weeks and burning down the plantations and freeing the Africans.

Dylan: I mean, I guess I have a question about Cuffy in this. Did he have a plan? Was there a sort of a goal at the end of this really clearly for Cuffy, or was it more sort of just like, “This is happening and I’m riding the wave”?

Baudelaire: It’s believed that the reason why Cuffy became the natural leader is that he had that vision for nationhood, right? So there were already maroon communities throughout Guyana and a lot of colonies throughout the Caribbean, right? Jamaica, Haiti, and whatnot.

But Cuffy didn’t want to become a maroon community. Aside from the fact that they’re actively fighting to liberate the other Africans throughout the colony, Cuffy’s also thinking when he goes plantation to plantation, like, “Okay, well, what are we going to do with this plantation once we have our nation?”

Dylan: So there’s a real ambition for kind of, “Okay, this is going to be a nation in the same way that France is a nation, that the Dutch are a nation. We are going to have our own statehood.” And that’s a pretty different aim than just like, “We’re throwing off the yoke of oppression.”

Baudelaire: And the capital of the colony was a fort called Fort Nassau, right? That is like the administrative and military headquarters of the colony, we’ll say. And as Cuffy and his men are moving closer and closer to the fort, he’s thinking further and further along of like, “Okay, well, like, how are we going to deal with this confrontation that’s going to happen ultimately between me and Van Hoogenheim?” Right?

Dylan: Yeah, and Van Hoogenheim has like what, a couple of dozen men? How many men at this point does Cuffy have?

Baudelaire: Cuffy has about 3,800.

Dylan: Okay, so you’ve got like 3,800 previously enslaved people, they have rebelled, they have taken control of a ton of land versus basically a couple of dozen Dutch guys in a little fort.

It seems like there’s a pretty clear path to victory that basically all Cuffy and his troops have to do is basically strike the fort and they win, right?

Baudelaire: Yes, but that’s not what Cuffy does. Instead, he sends Van Hoogenheim a letter.

Dylan: This—a letter, I see. This feels like maybe this is the act of civility that you teased earlier. Okay, well, what does this letter say?

Baudelaire: So basically it’s like, “Bro, we rebelled. And this is why we rebelled. I know you think we’re crazy, but you know as well as I do how brutal slavery was, right? And I don’t want this to end in any more bloodshed. So if you and, you know, those other people you got in the fort with you would kindly be on your way, go back to Europe, we’ll take it from here and everything could be cool.”

Dylan: I mean, this is kind of like, you can see the goal towards nationhood here because this is in a way trying to negotiate terms of surrender, right? It’s like, “We got you surrounded, you’re toast but we don’t have to kill you. Just surrender peacefully, leave, we’re all good. How does von Hoogenheim react to this letter?

Baudelaire: He decides like, “You know what? I don’t see the humanity in this other person, but I’m gonna write back.” Right? “I’m gonna see how far this can go.” Because von Hoogenheim knows he’s toast. He knows he doesn’t really have much options. You know, the letters are keeping him alive.

Dylan: Is this a good faith negotiation? Is he writing back being like, “Okay, we’re gonna withdraw,” or, “You take this land and we’ll stay in our little fort.” Like, what’s he saying?

Baudelaire: Well, the letters actually serve to really just buy time for these other letters he’s writing, right? The second set of letters that von Hoogenheim is writing is to neighboring Dutch colonies as well as to the British, basically saying, “We are dealing with a slave rebellion right now and whatever you guys got going on doesn’t matter because if these Africans, you know, successfully get rid of me, who’s to stop them from coming to Trinidad?”

Dylan: Suddenly every slave colony that we all are brutally oppressing and administering is at risk. So does anyone actually answer these letters? I mean, does anyone actually help them out?

Baudelaire: The British did. The British send 100 men to go and help von Hoogenheim, which still isn’t, you know.

Dylan: Not a ton against—

Baudelaire: Yeah. Not a lot. But it’s a hundred men plus supplies. And van Hoogenheim, of course, willingly takes this and is continuing writing to—he’s continuing writing to other colonies, just asking for more and more help.

So Cuffy is just thinking like—he shifts a bit. First he’s telling von Hoogenheim to leave, but then after, you know, a series of letters back and forth, he’s like, “All right, we’ll split this colony. But, you know, you guys are vastly outnumbered. So you guys will get this little piece.” Right?

Ultimately, Cuffy is trusting the process here, because von Hoogenheim is always responding to Cuffy’s newest offer with like, “You know, man, I’m just a governor here, right? I sent your offer back home.”

Dylan: Right. “Oh, I can’t—unfortunately, this does have to be sent back across the ocean to, you know, the Netherlands. Like they’re going to have to—you know …”

Baudelaire: “I agree with you.”

Dylan: “I would love to give you a nation, but unfortunately, the regulation ...” Yeah, right.

Baudelaire: “It’s above me.” You know what I mean? He had to go get his manager. So, while this is happening, Cuffy has Akara and Atta, these two militant men next to him that are like, “Bro, why are we even writing letters? What are we doing? Why is this even a thing?”

Which starts to cause a division between Cuffy on one side being more diplomatic and Akara and Atta on the other side saying, “Okay, we’ve tried this. It’s been months now. And this guy just is kicking the can down the road. Like they’re right there, the fort’s right there. Let’s go get them.” And what we also find out later is that the men that Cuffy was sending to get Van Hoogenheim’s letters, the deliverers of the letters, they got flipped by Van Hoogenheim. So Van Hoogenheim finds out that, “Oh, there’s division going on on you guys’ side.”

Dylan: Oh, right. The arguing between Cuffy and his second commanders. Yeah, yeah.

Baudelaire: Exactly.

Dylan: I feel like I know where this is going and it’s not great. So what happens here?

Baudelaire: Well, throughout the negotiations, Dutch ships start arriving at the coast of Berbice. And over some time, Van Hoogenheim now has enough men and supplies. Because one thing you also got to remember about the rebels: They got a limited amount of gunpowder.

They got a limited amount of everything. You know what I mean? So Van Hoogenheim now has what he needs to attack. At the same time, Akara, Atta, and Cuffy, their schism leads to a vote. A vote amongst the rebels on who the new leader will be. And Akara and Atta win. After losing his leadership, Cuffy deserts the men and takes his own life. Akara and Atta are now at the helm, and they now are able to go and attack the Dutch.

Dylan: And then what happens?

Baudelaire: By December 19th, 1763—so the end of that year—Akara and Atta are captured. That following year, in the first few months of 1764, 40 rebels hanged, 24 broken at the wheel, and 24 burned to death.

Dylan: Yeah, Cuffy was trying to walk a path that kind of didn’t exist. You know what I mean? Like, because the powers were unwilling to see enslaved people as human beings, but certainly not as any kind of power to be negotiated with, only to be blockaded and crushed and whatever, right?

Which is exactly what you see in the Haitian rebellion. So what happened after that? I mean, there must have been more rebellions. Like, what is sort of the ultimate story around Cuffy and Guyana and his sort of role in history?

Baudelaire: Yeah, well, the colony of Berbice changes hands. Eventually it becomes a British colony. The British rename it Guyana. And Guyana gains its independence in 1966. Four years later on the anniversary, February 23rd, 1970, the nation of Guyana proclaims Cuffy as the first national hero.

Dylan: That makes sense.

Baudelaire: Yeah. And a couple of years after that, a local artist is commissioned to start work on a statue to pay tribute to Cuffy and to the memory of the rebellion itself.

Dylan: Yeah. It’s funny, because this is the kind of statue, like it’s big, but it’s not so big that— it’s not some tower. You know, you might cruise by this and be like, huh, that’s a strange, unusual statue. But in there is so much of Guyanese history, you know? I mean, to be honest, I didn’t know a lot about Guyana going into this. And I had never heard of this rebellion or Cuffy. And this is like, what a kind of fascinating, heroic, tragic story. Thank you, Baudelaire.

Baudelaire: Cool. Thanks for listening.

Listen and subscribe on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

This episode was produced by Baudelaire.

Our podcast is a co-production of Atlas Obscura and Stitcher Studios.

The people who make our show include Doug Baldinger, Chris Naka, Kameel Stanley, Johanna Mayer, Manolo Morales, Baudelaire, Gabby Gladney, Amanda McGowan, Alexa Lim, Casey Holdford, and Luz Fleming. Our theme music is by Sam Tindall. If you like our show, please give us a review and a rating whenever you get a chance and wherever you get your podcasts.