The Bradbury Building Featured in ‘Blade Runner’ Was Inspired by a 19th-Century Utopian Novel

Listen and subscribe on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. There’s this very cool building in L.A. called the Bradbury Building. It’s an office building, it’s downtown. So you walk in and there’s this kind of dark, narrow hallway, but then as you go further into the building it opens up into this big atrium. You can see straight up to the ceiling. It’s made of glass, there’s these beautiful elaborate wrought iron railings going around everything, and there’s plants everywhere. And it honestly kind of looks like a steampunk greenhouse or something. This building has been in a ton of movies. The most famous is probably Blade Runner, which of course as you know is a dystopian vision of the future. But I was surprised to find when looking into the history of this building that it was actually inspired not by a dystopian view of the future, but by a utopian one. Specifically, it was inspired by a utopian novel written in the 1800s about time travel. And as it turns out, besides this very cool building in downtown L.A., this novel actually inspired quite a lot of other real world places and ideas too. I’m Amanda McGowan and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. Amanda McGowan: Nowadays, we hear a lot more about dystopias than utopias. I mean, picture just about any dramatic TV series you’ve probably watched in the last few years. But today, I want to look backwards at a utopian book with a big impact. Because of this book, new political parties were formed, people started communes to live on, and there’s even some surprising ripples in our own time from L.A.’s Bradbury building to one small Massachusetts town. Okay, time for a bit of a scene change. We’re going to leave the sunny world of Southern California and head to central Massachusetts to the town of Chicopee. Specifically, we’re going to go to this old 19th century house, which I imagine at this time of year—and maybe most times of year—is probably a little drafty and a little bit cold. Today, this house is actually a museum—a museum dedicated to a writer who used to live there: a guy named Edward Bellamy. But if you ask residents of Chicopee today about Edward, they might not know who you’re talking about. Jason Amos: There would be people who were visiting and had no idea who he was, even though the city has a middle school named after him. Amanda: This is Jason Amos. He’s head of the Edward Bellamy Memorial Association. So no, Bellamy, not exactly a household name today. But back in the 1890s, it was a totally different story. In America, there were only two books in the entire 19th century that sold more copies than Edward Bellamy’s most famous book. One of those was Ben-Hur, and the other one was Uncle Tom’s Cabin. But before we get to Bellamy’s book, I just want to say a couple words about his backstory. He was born and raised in Chicopee, but when he was young, he did some studying and traveling around Europe. Amos: When he came back, he said that it wasn’t the cathedrals or the palaces that he saw that stuck with him, but it was the poverty from industrialization that he saw. And when he came back to Chicopee, he could see the same sort of thing happening in his own city. Amanda: Chicopee at the time was changing from a farming town to a factory town. And actually, if Bellamy looked out his window from this house back then, he would literally see factories. And just a little bit further downhill, he would see tenement houses for factory workers. Bellamy himself kind of jumped around from job to job. He worked in law for a little bit, then he was in newspapers, but he suffered from bad health all of his life. And at one point, he ended up kind of dropping out of the news business and moved back to his parents’ house to try to write novels. So here’s where we can picture him sitting in Chicopee, looking out the window at the factories and the tenement homes and writing his most popular book, which is called Looking Backward. Okay, so Looking Backward, it’s about this guy named Julian West. He is a wealthy businessman in Boston, but he has trouble sleeping. So he hires a hypnotist to help him go to sleep. But the hypnotist is too good at his job. Julian West goes to sleep and when he wakes up, it is a year in the distant, distant future: the year 2000. And things look extremely different. Amos: He wakes up to find that the social order that he was accustomed to, that’s been entirely replaced by a new social order where everybody is working towards the common good for each other. Amanda: Julian West does not even recognize the place. He’s walking around Boston. There’s these gigantic, beautiful parks everywhere. There’s these big, beaut

Listen and subscribe on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

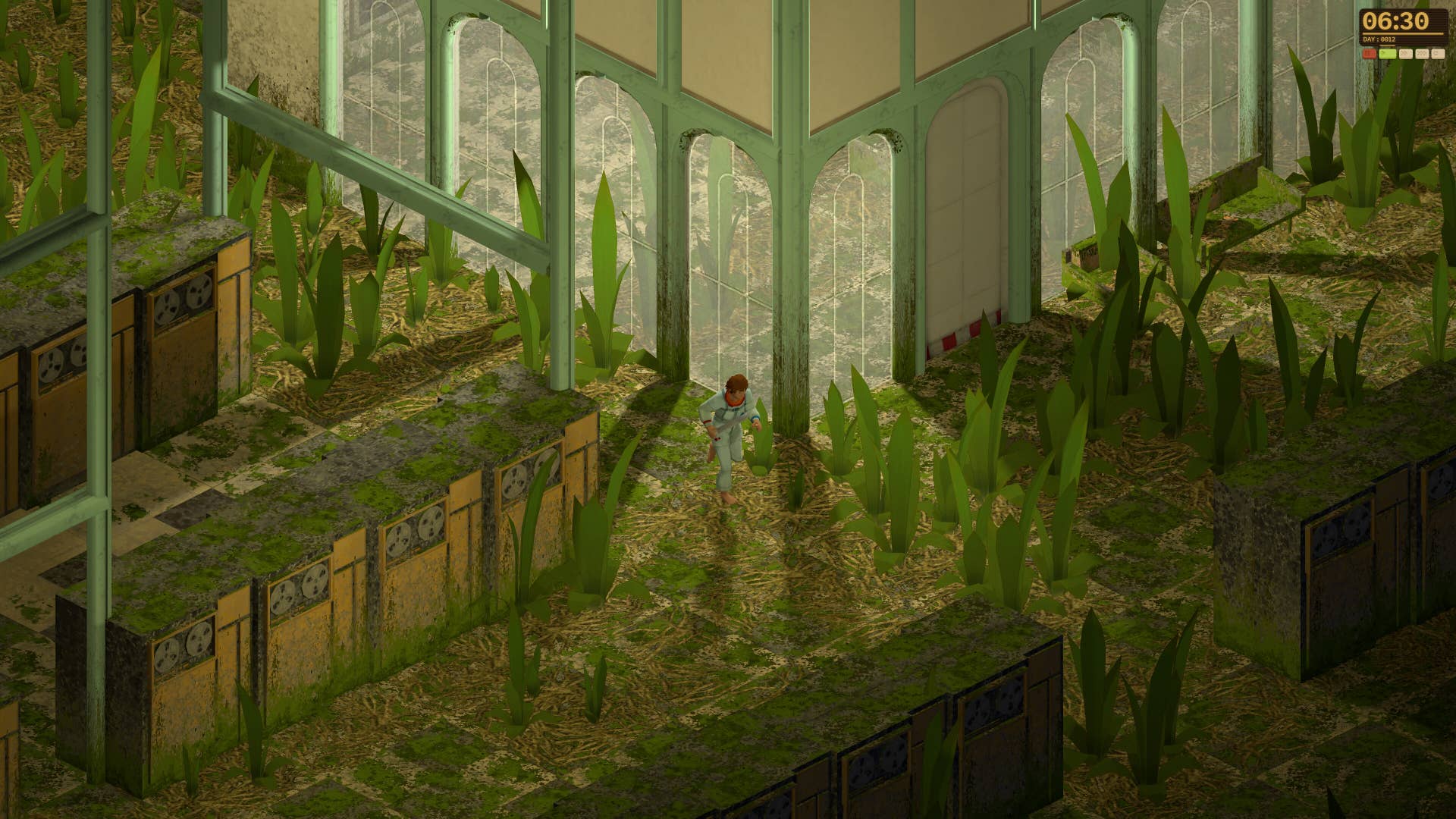

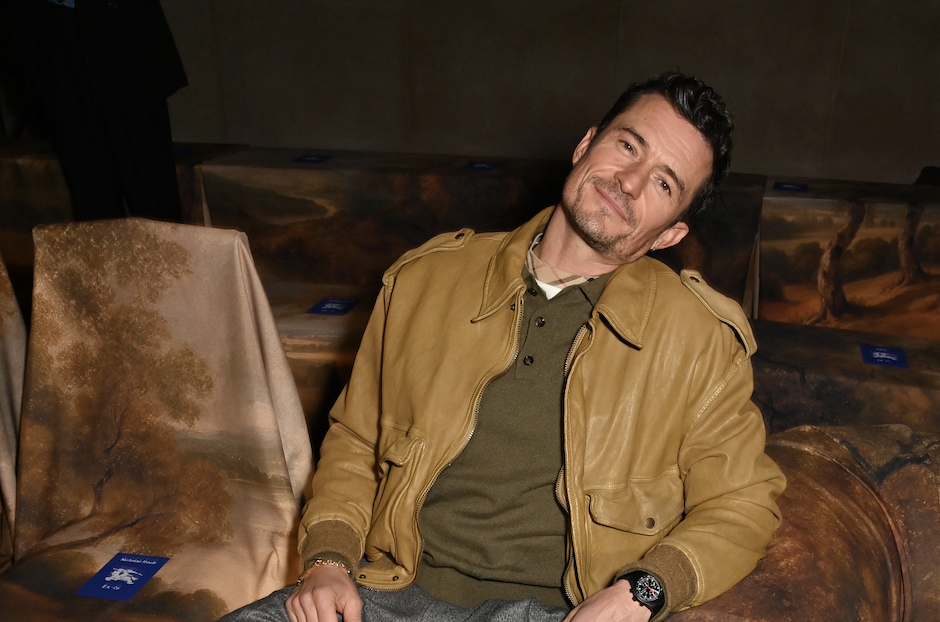

There’s this very cool building in L.A. called the Bradbury Building. It’s an office building, it’s downtown. So you walk in and there’s this kind of dark, narrow hallway, but then as you go further into the building it opens up into this big atrium.

You can see straight up to the ceiling. It’s made of glass, there’s these beautiful elaborate wrought iron railings going around everything, and there’s plants everywhere. And it honestly kind of looks like a steampunk greenhouse or something. This building has been in a ton of movies.

The most famous is probably Blade Runner, which of course as you know is a dystopian vision of the future. But I was surprised to find when looking into the history of this building that it was actually inspired not by a dystopian view of the future, but by a utopian one.

Specifically, it was inspired by a utopian novel written in the 1800s about time travel. And as it turns out, besides this very cool building in downtown L.A., this novel actually inspired quite a lot of other real world places and ideas too.

I’m Amanda McGowan and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places.

This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Amanda McGowan: Nowadays, we hear a lot more about dystopias than utopias. I mean, picture just about any dramatic TV series you’ve probably watched in the last few years. But today, I want to look backwards at a utopian book with a big impact. Because of this book, new political parties were formed, people started communes to live on, and there’s even some surprising ripples in our own time from L.A.’s Bradbury building to one small Massachusetts town.

Okay, time for a bit of a scene change. We’re going to leave the sunny world of Southern California and head to central Massachusetts to the town of Chicopee. Specifically, we’re going to go to this old 19th century house, which I imagine at this time of year—and maybe most times of year—is probably a little drafty and a little bit cold.

Today, this house is actually a museum—a museum dedicated to a writer who used to live there: a guy named Edward Bellamy. But if you ask residents of Chicopee today about Edward, they might not know who you’re talking about.

Jason Amos: There would be people who were visiting and had no idea who he was, even though the city has a middle school named after him.

Amanda: This is Jason Amos. He’s head of the Edward Bellamy Memorial Association. So no, Bellamy, not exactly a household name today. But back in the 1890s, it was a totally different story. In America, there were only two books in the entire 19th century that sold more copies than Edward Bellamy’s most famous book.

One of those was Ben-Hur, and the other one was Uncle Tom’s Cabin. But before we get to Bellamy’s book, I just want to say a couple words about his backstory. He was born and raised in Chicopee, but when he was young, he did some studying and traveling around Europe.

Amos: When he came back, he said that it wasn’t the cathedrals or the palaces that he saw that stuck with him, but it was the poverty from industrialization that he saw. And when he came back to Chicopee, he could see the same sort of thing happening in his own city.

Amanda: Chicopee at the time was changing from a farming town to a factory town. And actually, if Bellamy looked out his window from this house back then, he would literally see factories. And just a little bit further downhill, he would see tenement houses for factory workers. Bellamy himself kind of jumped around from job to job.

He worked in law for a little bit, then he was in newspapers, but he suffered from bad health all of his life. And at one point, he ended up kind of dropping out of the news business and moved back to his parents’ house to try to write novels. So here’s where we can picture him sitting in Chicopee, looking out the window at the factories and the tenement homes and writing his most popular book, which is called Looking Backward.

Okay, so Looking Backward, it’s about this guy named Julian West.

He is a wealthy businessman in Boston, but he has trouble sleeping. So he hires a hypnotist to help him go to sleep. But the hypnotist is too good at his job. Julian West goes to sleep and when he wakes up, it is a year in the distant, distant future: the year 2000.

And things look extremely different.

Amos: He wakes up to find that the social order that he was accustomed to, that’s been entirely replaced by a new social order where everybody is working towards the common good for each other.

Amanda: Julian West does not even recognize the place. He’s walking around Boston. There’s these gigantic, beautiful parks everywhere. There’s these big, beautiful public buildings that are like communal dining halls and all this stuff. And he’s like, who’s paying for this? But as it turns out, in the distant year 2000, America is a utopia, a socialist utopia, which I know is a little bit of a loaded term these days.

But in Bellamy’s vision, it’s kind of like the whole country was run like your local grocery co-op. Basically, the country is so technologically advanced and so productive that people only need to work 12 hours a week. Everybody retires at age 45 and the profits and goods produced are equally shared by everyone.

Education is free. No one is at risk of suffering or starving if they can’t work.

Like, for example, if they suffer from bad health. It’s kind of a crazy scene. There’s even some funky sci-fi futuristic gadgets in the book, or at least they would have seemed that way in 1888. Like this magical card that you can use to buy things, which today we might know as a credit card.

The other key thing is that Bellamy’s utopia is achieved nonviolently. There is no revolution. It comes about as more of a gradual, peaceful evolution.

Amos: He wrote it specifically with the idea that better days are ahead of us and not behind us, and that the natural evolution of things will actually lead to something good for everybody. And it didn’t need to be a win-lose situation for everyone. Everybody could win.

Amanda: Looking Backward was published in 1888, and over the next few years, it really took off, selling hundreds of thousands of copies. Americans seemed to really like what Bellamy was saying and the vision that he had for the future. And to understand why, it helps to know a little bit about what was going on in the country at the time.

Amos: It’s the Gilded Age, so there’s a large accumulation of wealth and capital amongst very few people. Immediately before he starts writing the book is the Haymarket Affair in Chicago, where people were protesting for eight-hour work days. So he’s really writing this in response to everything that is going on in terms of social issues and labor issues.

Amanda: And here’s what I found pretty amazing and also surprising. A lot of people took Bellamy’s ideas from this novel about a guy who gets hypnotized and travels to the future, and they actually went about trying to find ways to bring these ideas to life.

So let’s zoom in on just a couple of them.

Amos: The year after it was published, there were actually two clubs that were formed in Boston to sort of bring about his ideas called Nationalist Clubs or Bellamyite Clubs. And in a very short period of time, those sorts of clubs expanded to everywhere in the country. And eventually, it grew international to the point where even after Bellamy died and into the 1950s, the family was receiving mail from people who fully supported and believed in his ideas.

Amanda: Some of these clubs got into some very interesting activities.

If I say the word commune, probably you think of the 1960s and the hippie movement, but there were Bellamyites running with this all the way back in 1890. There was a Bellamyite commune in Washington State, one in Northern California, and they actually seemed to thrive for a few years, some of them even decades before fizzling out or dissolving because of commune drama.

Other clubs took a different approach. They decided they were going to get involved in local politics. And this is actually what Bellamy himself did in his home state of Massachusetts.

Amos: Bellamy was involved with the clubs in Boston. The clubs were the sponsors of a bill from the Massachusetts state legislature to allow cities and towns to have municipal electricity and utilities.

Amanda: Maybe that sounds a little bit unexciting, but campaigners saw this as a first step of moving toward Bellamy’s full grocery co-op-like society, where the public owned everything. Finally, looking backward influenced a whole generation of architects and city planners and inspired them to design these sort of grand parks and public places, just like the ones that Julian West saw when he was wandering around the Boston of the future.

In Milwaukee, planners used the book to develop ideas for connected greenways and parks. Then there were people like George Wyman, this architect in Southern California. Wyman had read Looking Backward and been inspired, it seems, by this particular passage when Julian West is looking around.

He says, “We turned in at the great portal of one of the magnificent public buildings I had observed in my morning walk. It was the first interior of a 20th century public building that I had ever beheld, and the spectacle naturally impressed me deeply. I was in a vast hall full of light, received not alone from the windows on all sides, but from the dome, the point of which was 100 feet above.”

Wyman went on to design an office building in downtown L.A. called the Bradbury Building, and this is the building we were talking about in the beginning of the episode.

If you visit the Bradbury Building, it’s almost like you can get a feel for the world of Looking Backward, almost like you are Julian West visiting the future.

But as you’ve probably noticed, we do not currently live in a utopia where the profits of everything are shared and everyone retires at age 45.

So what happened? It seems like as Bellamy’s ideas gained steam, they kept getting absorbed by bigger and bigger political movements. So in the 1890s, a few years after Looking Backward was published and the Bellamyite clubs got off the ground, there was this new political movement called the Populist Party, and it kind of adopted Bellamyist ideas and actually won elections in a number of states.

But then the populace got eaten by a bigger national political fish, and you’ve probably heard of them before.

Amos: So by 1896, the Populist Party is sort of absorbed into the Democratic Party.

Amanda: Bellamyist economic ideas definitely got watered down. It seemed like the focus shifted from the grocery co-op model to just focusing on regulating capitalism and industry. But his social ideas did take off.

I mean, some political scientists have drawn lines between Looking Backward and the New Deal of the 1930s, and actually FDR even had a copy of Looking Backward in the White House library while he was president. Sadly, Bellamy himself did not live to see much of this.

As I mentioned earlier, he was kind of sickly throughout his life. And in 1898, he died of tuberculosis just shortly after publishing a follow-up book to Looking Backward called Equality.

Now, I have to say that one of the things that drew me to this story in the first place was basically, I have dystopia fatigue. So much of our pop culture from TV, novels, movies, it’s all dystopian. And don’t get me wrong, I love Severance as much as the next person, but I have to wonder if we’re missing out on something by always imagining the worst possible scenarios in our art and not thinking of better ones.

So I posed this question to Jason. What if Looking Backward had been a dystopian novel instead of a utopian novel? Would it have had the same impact?

Amos: I think that Bellamy writing it with the hope that, you know, better days were ahead sort of made it more enjoyable to people rather than if something were, “Oh, well, doom and gloom,” and “Well, the future is bleak.” I think by writing it as “The future is brighter,” probably allowed it to become more popular than if he hadn’t.

Amanda: And what do we get from imagining better futures? Well, if we go back to Chicopee, Massachusetts, Edward Bellamy’s hometown, you’ll recall that the Bellamyite clubs there helped pass a law that allowed for municipal electric and gas—so, utility companies owned by the public and not for profit.

Amos: And Chicopee just so happens to be one of the cities that decided to run with municipal electricity. And now they have municipal internet as well.

Amanda: I mean, have you paid an electric or internet bill recently? That ain’t nothing.

The Bellamy House is a museum today. You can check it out. We will post information in the episode description. Put some info in there, too, about the Bradbury Building and other links about Edward Bellamy and his book.

And Looking Backward is in the public domain, which is something I imagine Edward Bellamy would be pretty pleased about. It’s on Project Gutenberg. We’ll link to that, too.

Listen and subscribe on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Our podcast is a co-production of Atlas Obscura and Stitcher Studios. The people who make our show include Dylan Thuras, Doug Baldinger, Chris Naka, Kameel Stanley, Johanna Mayer, Manolo Morales, Baudelaire, Alexa Lim, Casey Holford, and Luz Fleming.

Our theme and end credit music is by Sam Tindall. And if you like our show, give us a good review and rating wherever you get your podcasts.

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)