While Fortnite flourished, one team member spent nights building his dream miniatures game

Best Hobby founder Daniel Block has, well… been around the block a few times. At 51, he’s already had an incredible career in tabletop gaming, first in the 1990s working on card games like Rage, Legend of the Five Rings, and Dune: Collectible Card Game. He then pivoted to video games, first joining up with […]

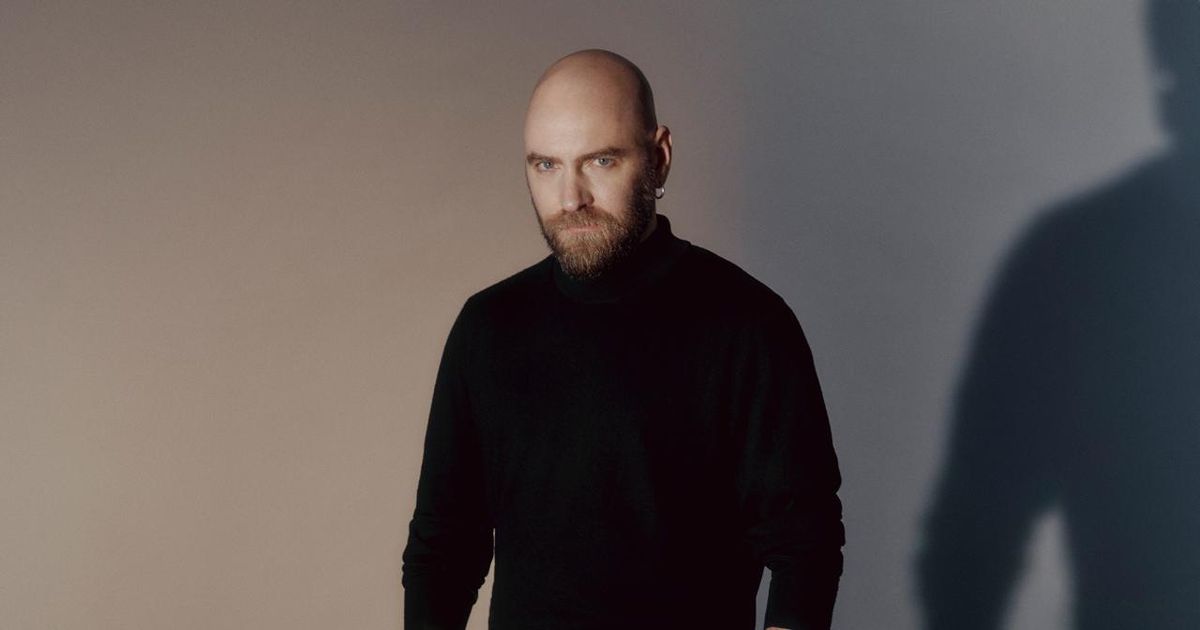

Best Hobby founder Daniel Block has, well… been around the block a few times.

At 51, he’s already had an incredible career in tabletop gaming, first in the 1990s working on card games like Rage, Legend of the Five Rings, and Dune: Collectible Card Game. He then pivoted to video games, first joining up with Eve Online publisher CCP Games, and then moved on to Riot, where he had a hand in League of Legends as well. But that may as well have been the prelude to the role that would enable his early retirement — setting up the publishing team that helped launch Fortnite and other titles on the Epic Games Store.

Rather than put aside his nest egg for a proper retirement, he’s opted instead to go all in on something even more ambitious through a new company, the innocuously named Best Hobby. From a tiny warehouse space that he rented out just before the COVID-19 pandemic, he’s concocted a plan to rediscover the art and craft of making plastic miniatures right here in the United States. His first project is for a game called Zeo Genesis, and it launches on Gamefound April 29.

“Miniatures are a cruel mistress and they will break your heart if you’re not careful,” Block says. “But [the desire to make a game like this has] always been there, for 25 years now. It’s been the burning thing. I’ve always said, ‘If I ever reach the point that I get to choose what I do and go out on a limb, go out on a plank, take the risk, make the leap, I’m going to make the miniatures game.’”

With so much at risk, he’s certainly found some great partners to help in the work — veteran Warhammer 40,000 game designers and authors Andy Chambers and Gav Thorpe. Polygon recently spoke with all three.

The Hundred Suns

Zeo Genesis is a miniatures skirmish game, a style of game that’s exploding in popularity right now both online and at retail. It’s a genre of wargame that can easily be played on a kitchen table, using only a dozen miniatures or less and elaborate terrain, along with rulers and dice. There are established titles in the genre, of course — games like Necromunda, Warhammer 40,000: Kill Team, BattleTech, Marvel: Crisis Protocol, and Infinity, but also upstarts like Trench Crusade, Star Wars: Shatterpoint, Halo: Flashpoint, and Fallout: Factions. It’s easily one of the most dynamic spaces in all of tabletop gaming, but the competition for consumer attention is fierce.

Narrative lead Gav Thorpe’s mission, therefore, is to try and make Zeo Genesis the most interesting and engaging universe of all, with a fiction that feels just as compelling as the hobby itself. The setting that he’s helped create is a discrete set of human-occupied worlds known as the Hundred Suns.

“It consists of 100 star systems,” Thorpe says, “[that are] linked together by a special system of navigation called Slipways.”

Each of those Hundred Suns is bounded by a hard perimeter that simply can’t be passed through by terrestrial starships, a terminator known as “the limit” or “the barrier.” Over thousands of years, the humans in the Hundred Suns have created a model of how the Slipways all connect to one another, a complex orrery of thousands of celestial bodies that in no way respects traditional concepts like adjacency or linear space. The thing is that no one really knows why barriers were put there in the first place, or by whom.

“Nobody’s sure if the barrier’s there to keep them in, or to keep something else out,” Thorpe says. That’s resulted in all manner of conflicts between and among the civilizations of the Hundred Suns — especially now that one of those worlds has become disconnected from all the others, a story being told right now through a corresponding webcomic.

As tensions surrounding the disappearance of this missing world heat up, these pockets of humanity have organized themselves into two very different factions known as Hegemony and Pact. The Hegemony faction is, by and large, made up of the established capitalist entities that own the land on the surface of the Hundred Suns’ many worlds, and which profit from the trade between star systems. The Pact is a bit more like a powerful band of well-organized space communists, a star-spanning coalition of laborers, explorers, and scientists who make their living and their way of life traveling between the Hundred Suns.

“There’s the core worlds, the oldest and the first- and second-generation worlds, [that] are obviously a lot more settled, more civilized,” Thorpe says. “And as you get into some of the more newer ones, it’s much more frontier, Wild-y West, all those kinds of things — and the politics that goes with that.”

As these heliospheres, as each of the Hundred Suns star systems are called, go swirling about in their non-Euclidean fashion and the larger political entities bring their ideologies to bear, both the Hegemony and the Pact do battle using very similar technology — something called a Zeoform.

Zeoforms

Zeoforms are giant robots that human pilots can learn to control using underutilized portions of their existing brains, like grafting phantom mechanical limbs onto their fleshy bodies. Both the Pact and Hegemony use these machines for performing heavy or dangerous labor. But in the Hundred Suns, zeoforms are also used to wage limited warfare — you know, violent insurrections, police actions, assassinations, coup d’état… that sort of thing.

Thorpe is clear that this isn’t a world of endless war, but instead something more akin to our own modern-day Earth with long-simmering conflicts and proxy fights between superpowers, where regular folks are just trying to exist peacefully when the laser beams start to fly.

“It’s not a thousand zeos dropping out of the sky,” Thorpe says. “It’s three or four zeos trying to blow up an oil refinery, or take a gas harvesting dirigible, or whatever.

“This is a setting about humans,” Thorpe added, “[and] the most important thing [is] how technology affects them.”

When conflict does break out, says game lead Andy Chambers, those limited battles are invariably nasty, brutish, and short. The in-fiction reason is that zeoforms tend to run hot and can only sustain pitched combat for short periods of time. These aren’t skyscraper-sized mecha pounding city blocks flat with their massive feet, but something smaller and a little bit more intimate — and the rule system itself reflects that.

The game in motion

“Back in the ’90s — way back when — we kind of came to this conclusion that most games basically give you a two-action system when you activate a unit,” Chambers says. “You can move and you can shoot. […] Or you can double move. And that was the way it generally functioned. [But] what happens if we give you three actions in a row instead? How does that change things? And the answer is quite a lot.”

Building on a dice-based combat model first developed by designer Ryan Miller before he joined Ravensburger to build Disney Lorcana, Chambers and Thorpe have devised what they believe is a highly flexible and reactive system of play. Each player performs a singular three-action activation of a unit on their turn, and play proceeds back and forth until one side has activated all of their units. That’s when one side of the table must regroup, taking a tactical pause before gathering their wits and proceeding on to the next stage of the fight.

“You’re busy getting your activation points back,” Chambers says, “so your opponent will get a free go, in effect. They’ll get to do two [rounds] back to back because you have to regroup, which is a bit of a watershed moment — [and] it can tip things quite nastily.”

Players can reserve action points, using them to interrupt enemy actions on the other player’s turn. But part of the metagame in Zeo Genesis is building a force that can easily overcome the need to take a pause and regroup, one able to press the enemy while also giving themselves enough room to breathe. The game’s human-sized and smaller units aren’t merely there just to show the scale of the hulking zeos, but to help give a locus of power to unique and potent abilities that can impact things like the flow of battle and unit morale.

“You can have troopers, or you can have a zeo, […] that’s a squad leader,” says Thorpe, whose narrative chops have clearly impacted the game design here as well. “You get to basically chain-activate several models. So those [models] suddenly become really valuable things. Or sometimes it’s a pain because, Well, actually, I don’t want to use three of my models up yet.”

The pair tell me that it all adds up to a game with lots of theory-crafting as well as delicious hobby prep work, one that resolves through a blisteringly fast 45-minute-to-one-hour game.

“There’s not lots of turns,” Thorpe says. “Generally [only] one or two regroups [per game], and some scenarios deliberately limit you [to] one — or none. So you have to get stuck in [right from the jump]. It’s forcing you to act, forcing you to do stuff, not just sit at the back and trade shots.”

“We put a really, really strong bent on the dynamic action side of things,” Chambers adds, citing a cinematic feel inspired by ’90s anime.

Building for the future

Best Hobby owner Daniel Block has clearly done his homework. Not just with the product pipeline, which he says is more or less finalized with the rollout of new rules, models, and factions laid out for months and years to come following the initial Gamefound campaign. He’s also got his arms around the technical side of things as well. That’s because while the rest of us spent the pandemic making sourdough bread and farting around in Animal Crossing: New Horizons, he was heading home from his day job at Epic to teach himself how to make plastic miniatures using high-tech software and industrial machinery.

Turns out that manufacturers here in the United States are woefully behind when it comes to crafting the detailed metal molds required to make plastic miniatures at scale. Block thinks he’s cracked the code, and if he’s right it could unlock plenty of opportunity for Best Hobby — and maybe even for other domestic publishers as well.

“The secret of everything about making injection-molded miniatures,” Block says, “is […] the mold. If you can make the mold, and you can make it in a sustainable, repeatable way, that is what unlocks [the] business.”

Only now, Block says, after years of tinkering more or less in secret, does Best Hobby have what it takes to even consider matching the quality of Games Workshop, a company that he calls the “the most disruptive of all tabletop companies.”

“For 25, 30 years they’ve been doing it better than anybody,” Block said. “Instead of making modern weapons, or flight frames, or milling the inside of micrometer[-sized] widgets, they were making toy soldiers.” Now, he says, that same level of technology is available for a price on the open market. All it takes is the time, dedication, and resources to master it.

The only question is if fans will show up once the polystyrene forges get lit here on the other side of the Atlantic.

“There are people who are going to do more onshore plastics,” Block said, referring to other domestic competitors he expects will likewise soon break cover with their own manufacturing solutions. “What I hope is we have the creative and the industrial capacity, because what I see with some of the other folks who are coming along the same path we are, I haven’t seen their creative iteration yet.”

Now it only remains to be seen if he can press his advantage for one more turn, or if he and his collaborators will be forced to pause and regroup.

“Creative endeavors are expensive because they’re all risk,” Block said. “We think the world wants it. We’re going to do our damnedest to make sure the world actually knows what it is and has a chance to get into it. But it’s all risk.”

The Gamefound campaign for Zeo Genesis begins April 29. Expect a two-player starter set, complete with miniatures and terrain, to run about $150, while a single-player option will be priced around $60, a selection of which will begin shipping this December. The rules, currently available as part of an open playtest, will always be available for free online.

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)