A Man in 19th-Century Italy Preserved His Own Brain to Fight Eugenics

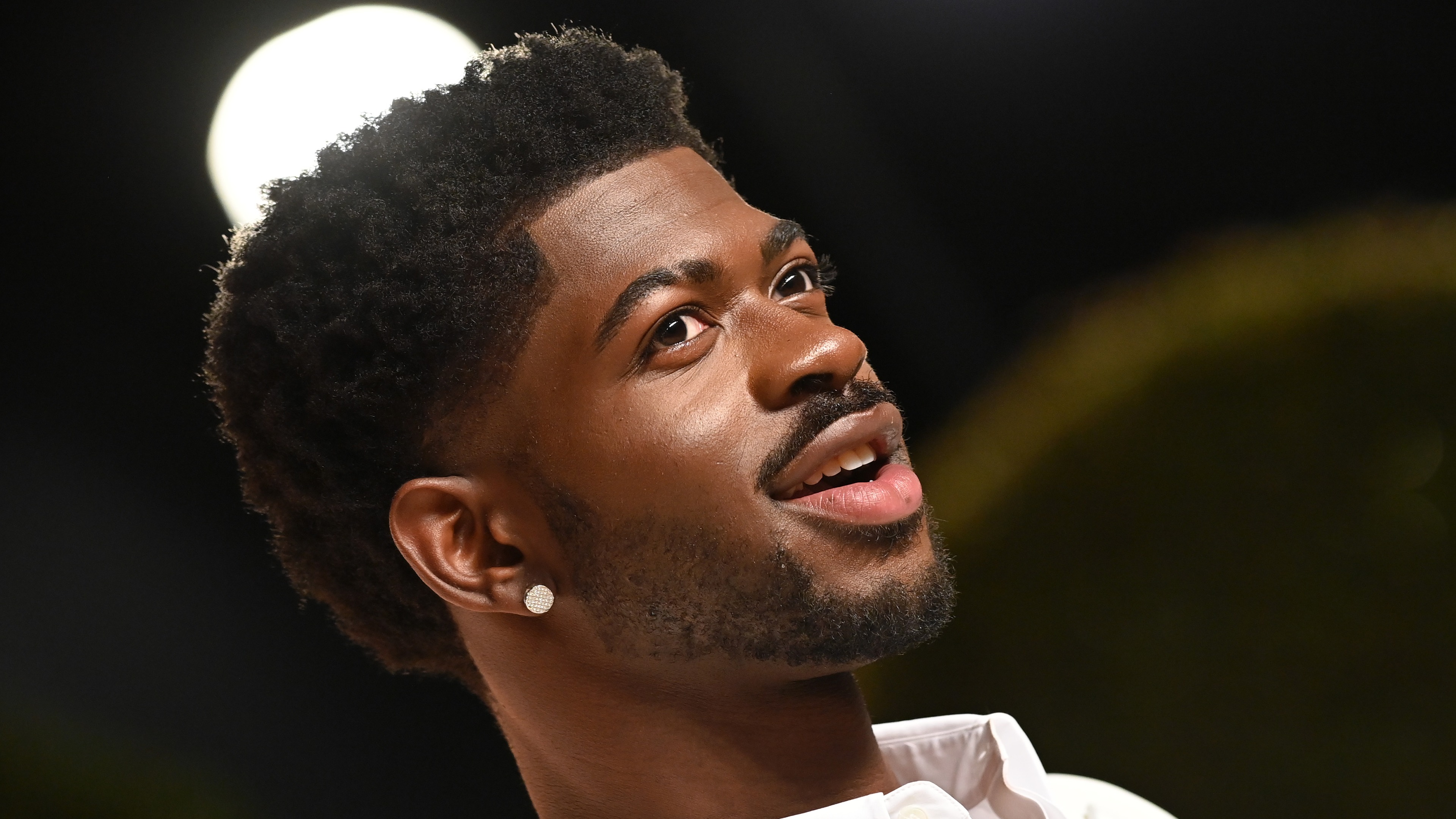

Tucked between the tibias of a standing skeleton in a museum in Turin, Italy, is a peculiar glass dome. The small container almost escapes notice, located in the last room of the Luigi Rolando Museum of Human Anatomy. Despite the wooden plaque below the item, the explanation just raises more questions. “Being neither an advocate of cremation nor cemeteries, I would like my bones to be laid to rest in the Anatomical Institute,” the inscription reads. “I would also like my brain to be preserved with my method and placed in the Museum together with the others.” The words are taken from the last will of Carlo Giacomini, and the item on display is his brain. Giacomini was an anatomist, neuroscientist, and museum director from the 1800s who proposed a new way to preserve brains. His recipe essentially dried the organ out, while maintaining all the significant features. Today, his own brain is slightly shrunken and has a dark brownish color. And it’s not the only one. Within the museum are five cases filled with 800 human brains, all prepared by the same man. Some of them are labeled Cervelli di criminali, or “Criminals’ brains.” Though he didn’t know it at the time, Giacomini’s work became part of a bigger conversation involving eugenics, Nazis, and a division of neurocriminology today. When Giacomini was in medical school, scientists of the day were hotly debating phrenology, a new school of thought that claimed physical characteristics could reveal internal aspects of an individual. Franz Joseph Gall first proposed the idea in the early 1800s that criminal behavior was determined by biology and was even apparent in the shape of a skull. But it was Cesare Lombroso who popularized the theory when he established the Positivist School of Criminology in Italy. Lombroso believed the brain’s morphology was responsible for violent, antisocial, or genius behavior. He claimed that criminal dispositions were biologically inherited, identified from a unique physiological signature, and therefore unchangeable—in other words, individuals were born criminals and were predetermined to commit violent crimes. Lombroso’s ideas were widely influential in criminal law in both Europe and the United States in the late 1800s, and were often used to support crude racial and class-based stereotypes of criminal behavior. “Such theories confirmed the superiority of the white male intelligence and the legitimization of colonial power,” says Cristiane Augusto, a researcher and expert in Penal Right at the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Lombroso wanted anatomical proof of his theories, so he enlisted Giacomini, who ran in the same scientific circles. Lombroso procured the brains from recently deceased individuals and gave them to Giacomini. Most of the specimens came from a hospital, but some were from individuals who died in prison. The only problem in studying brains was how quickly they fell apart, so something had to be done to preserve them. Scientists had previously attempted to preserve the brain with both liquids and dehydration, but Giacomini had deemed all known methods unsatisfactory. Liquids were expensive, needed to be changed every few years, and made observations more difficult, whereas current drying methods caused cracks and a marked reduction in volume. The organ is extremely delicate. “In certain seasons of the year,” Giacomini wrote in Guide to the Study of the Cerebral Convolutions, “the brain is so soft when it is extracted from its cavity 24 hours after death, that it would be almost impossible to remove its membranes to make the convolutions more visible.” The only solution, he thought, was to try to harden the brain. Giocomini injected the brains with or immersed them in zinc chloride, glycerine, nitric acid, or potassium bichromate. After a few days, the organs would dry out, becoming “more durable and less subject to deterioration,” he wrote. “Preparations made with the drying method not only gave the anatomical specimen greater consistency but, more importantly, eliminated deformations, making observations more reliable,” says Giacomo Giacobini, the current director of Turin’s anatomical museum. Giacomini prepared more than a thousand brains using his new methods. He then carefully studied the organs for years, measuring and comparing the cerebral matter of different specimens. And his conclusions did not make Lombroso and many of his colleagues very happy. He stated unequivocally: “We do not find that the brains of social misfits have a specific type of conformation, but rather the same variations, in the same proportions, as other brains, and we can in no way relate these variations to their malevolent actions.'’ However, his views were never acknowledged by a wider audience. Some of his opponents claimed Lombroso was improving upon Darwin’s theory of evolution by expanding the idea to social evolutionism. They therefore dubbed Giacomini as a “theologian and fearful individual” w

Tucked between the tibias of a standing skeleton in a museum in Turin, Italy, is a peculiar glass dome. The small container almost escapes notice, located in the last room of the Luigi Rolando Museum of Human Anatomy. Despite the wooden plaque below the item, the explanation just raises more questions. “Being neither an advocate of cremation nor cemeteries, I would like my bones to be laid to rest in the Anatomical Institute,” the inscription reads. “I would also like my brain to be preserved with my method and placed in the Museum together with the others.”

The words are taken from the last will of Carlo Giacomini, and the item on display is his brain.

Giacomini was an anatomist, neuroscientist, and museum director from the 1800s who proposed a new way to preserve brains. His recipe essentially dried the organ out, while maintaining all the significant features.

Today, his own brain is slightly shrunken and has a dark brownish color. And it’s not the only one. Within the museum are five cases filled with 800 human brains, all prepared by the same man. Some of them are labeled Cervelli di criminali, or “Criminals’ brains.”

Though he didn’t know it at the time, Giacomini’s work became part of a bigger conversation involving eugenics, Nazis, and a division of neurocriminology today.

When Giacomini was in medical school, scientists of the day were hotly debating phrenology, a new school of thought that claimed physical characteristics could reveal internal aspects of an individual. Franz Joseph Gall first proposed the idea in the early 1800s that criminal behavior was determined by biology and was even apparent in the shape of a skull. But it was Cesare Lombroso who popularized the theory when he established the Positivist School of Criminology in Italy. Lombroso believed the brain’s morphology was responsible for violent, antisocial, or genius behavior. He claimed that criminal dispositions were biologically inherited, identified from a unique physiological signature, and therefore unchangeable—in other words, individuals were born criminals and were predetermined to commit violent crimes.

Lombroso’s ideas were widely influential in criminal law in both Europe and the United States in the late 1800s, and were often used to support crude racial and class-based stereotypes of criminal behavior. “Such theories confirmed the superiority of the white male intelligence and the legitimization of colonial power,” says Cristiane Augusto, a researcher and expert in Penal Right at the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.

Lombroso wanted anatomical proof of his theories, so he enlisted Giacomini, who ran in the same scientific circles. Lombroso procured the brains from recently deceased individuals and gave them to Giacomini. Most of the specimens came from a hospital, but some were from individuals who died in prison.

The only problem in studying brains was how quickly they fell apart, so something had to be done to preserve them.

Scientists had previously attempted to preserve the brain with both liquids and dehydration, but Giacomini had deemed all known methods unsatisfactory. Liquids were expensive, needed to be changed every few years, and made observations more difficult, whereas current drying methods caused cracks and a marked reduction in volume. The organ is extremely delicate. “In certain seasons of the year,” Giacomini wrote in Guide to the Study of the Cerebral Convolutions, “the brain is so soft when it is extracted from its cavity 24 hours after death, that it would be almost impossible to remove its membranes to make the convolutions more visible.” The only solution, he thought, was to try to harden the brain.

Giocomini injected the brains with or immersed them in zinc chloride, glycerine, nitric acid, or potassium bichromate. After a few days, the organs would dry out, becoming “more durable and less subject to deterioration,” he wrote.

“Preparations made with the drying method not only gave the anatomical specimen greater consistency but, more importantly, eliminated deformations, making observations more reliable,” says Giacomo Giacobini, the current director of Turin’s anatomical museum.

Giacomini prepared more than a thousand brains using his new methods. He then carefully studied the organs for years, measuring and comparing the cerebral matter of different specimens. And his conclusions did not make Lombroso and many of his colleagues very happy.

He stated unequivocally: “We do not find that the brains of social misfits have a specific type of conformation, but rather the same variations, in the same proportions, as other brains, and we can in no way relate these variations to their malevolent actions.'’

However, his views were never acknowledged by a wider audience. Some of his opponents claimed Lombroso was improving upon Darwin’s theory of evolution by expanding the idea to social evolutionism. They therefore dubbed Giacomini as a “theologian and fearful individual” who stood against Darwin (which was false), and discarded his conclusions altogether.

Though Giacomini’s method was used extensively by some Italian scientists, it became obsolete as new technologies, such as digital angiography, allowed a more sophisticated mapping of the human brain. His conclusions, though, became prevalent in the aftermath of World War II. In the wake of Nazism, Lombroso’s views were widely dismissed, considering their problematic relationship with scientific racism and eugenics.

But the idea of linking positive or negative attributes to the cerebral cortex didn’t disappear. Today, the scientific community at large assumes that all mental activities produce electrical, magnetic, or metabolic signals that new technologies are able to read. Highly technological tomographies perform exams in which it is possible to see the brain in action. Neurocriminology defends the idea that alterations in the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hypothalamus can lead to reduction of self control and anger management, predisposing a person to violence.

“Of course we emphasize that brain mechanisms underlying aggression do not stand in isolation, but represent a component of the larger biopsychosocial framework from which we view crime,” remarks Adrian Raine, author of The Anatomy of Violence and one of the most notable proponents of neurocriminology. “But as we begin to see the evidence for biomarkers as incontrovertible, then what should we do about them?”

Some legal defense teams, particularly in the U.S., have started using brain scans and neuroscience as mitigating evidence in the trials of violent criminals and sex offenders. Yet sociologists and bioethicists express concerns about the dangers of such an approach. “While it is certainly possible to observe a correlation between biological mechanisms and behavioral patterns, this does not directly imply causality,” explains Giorgio Gristina, a researcher at the Systems Neuroscience Laboratory in the Champalimaud Center for the Unknown.

In the debate of nature versus nurture, it’s difficult to disregard someone’s surroundings, since, as neurocriminology affirms, the brain is a malleable organ. “Environmental factors can change the physical structure of the brain,” adds Jaime Arlandis, a researcher also at the Champalimaud Center. Gristina and Arlandis believe one’s actions are not predetermined by the brain they were born with, but that the brain can change over the course of one’s life.

Who knows if Carlo Giacomini would have realized this debate would continue well beyond his own death. His work in preserving and studying brains was a precursor to neuroscience today, but the answers are still as mysterious as the brain itself, which modern scientists are only beginning to understand.

Did Giacomini realize more work was needed? Is that why he preserved his own brain and left it for all to see? Those answers may be locked in the hardened cerebral mass sitting on display in Turin. All we can do is quietly look at his physical mind and wonder.

-Baldur’s-Gate-3-The-Final-Patch---An-Animated-Short-00-03-43.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)