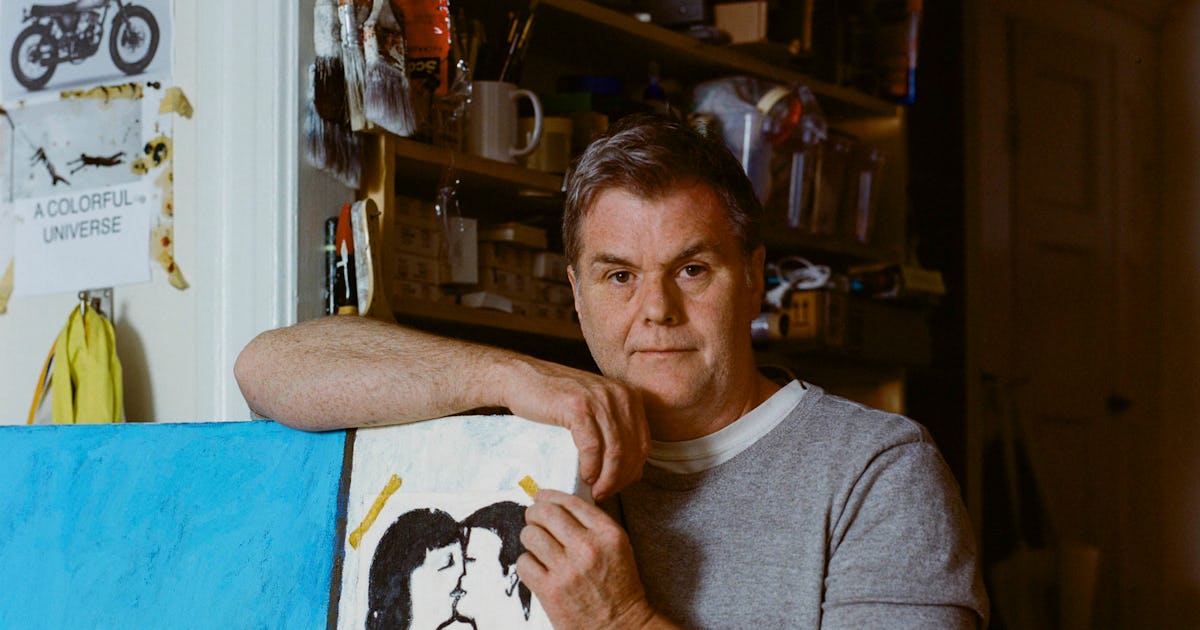

Artist Mark Milroy Is Playing the Long Game

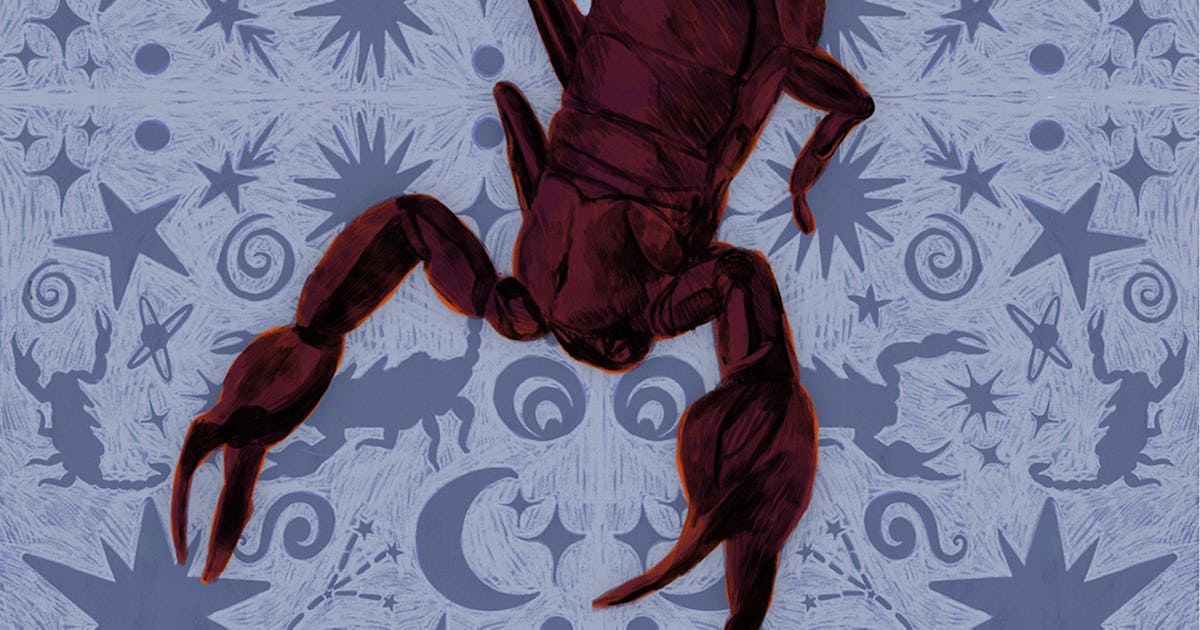

The painter’s new show at Pamela Salisbury Gallery, ‘A Colorful Universe,’ captures the slow, exacting nature of his work.

It took 20 years for the artist Mark Milroy to work up the gumption to attend the New York School of Art. At least, that’s the way the 57-year-old painter tells it, on a sunny spring morning visit to the Brooklyn shotgun apartment and studio he shares with his partner and muse, the arborist Lindsey Testolin. What Milroy leaves unsaid is that he’s been a lifelong student of art, and that his game is long. “A little bit every day can add up to a whole lot,” he says, in an accent that toggles between a Midwestern hush and Canadian idioms. His paintings are made in weeks, months, or years, and line the walls of his home.

Milroy grew up as an undiagnosed dyslexic in a house of six siblings. In school, he got little positive feedback, except on the basketball court; as a result, he channeled his energies there, running drills alone day after day. When his dad moved the family from Minnesota to Ohio to Canada, his sports prowess became the universal language out of which Milroy constructed new friend groups. It was, funnily enough, his pursuit of a degree in physical education that would lead Milroy to art, which he first encountered during his foundational courses at University of Western Ontario Canada. Ordinary schoolwork often just resembled “alphabet soup” to him, but art was a new venue for Milroy to show off his ability for disciplined, hands-on learning. His devotion to his work quickly gained him the attention that he craved at home and was repeatedly denied in the classroom early on; over time this passion evolved into a daily practice that Milroy still treats with the seriousness of a calling.

College was also the first place where Milroy came into contact with the artistic canon. His early paintings gained him comparisons from a professor to Oskar Kokoschka and Chaim Soutine; once Milroy discovered their names, he threw himself into the deep end, repeatedly recreating their paintings in study of their secrets. He kept this habit up for years, exploring different artistic voices until he consolidated his own wondrous, urgent, and athletic approach to mark-making.

“You have to learn their work inside and out in order to be able to move forward,” Milroy says of his artistic heroes. The sagging bookshelves of his library stand as a testament to Milroy’s commitment. I spy a bookmarked monograph of Pierre Bonnard, someone Milroy dismissed early on as a dabber and came back around to. He also has copies of the Met’s Siena show catalogue and a recently released Derek Jarman volume lying around.

After some catalyzing life events, including a heart-wrenching divorce and a more literal heart issue—one that required surgery—Milroy decided that it was now or never to make it as an artist in New York. After years of commuting from Northeastern Pennsylvania, he decided to commit to living in the city full time and attending The New York Studio for his MFA. Going back to school represented a shortcut to building the community of peers that Milroy craved. He also definitively claimed his point of view, notably with a series of paintings featuring the chalkboards and classroom exercises that had once humiliated him as a boy. “If I just paint my story and paint my life, then it’s mine,” Milroy says. “I can own it.”

During our visit, Milroy is putting the finishing touches on “A Colorful Universe,” an exhibition at Pamela Salisbury gallery in Hudson, New York, on view from May 17 to June 15. The show will feature 12 recent paintings; some of them started as memories, and others capture recent moments, both staged and candid. “I like vacillating between this idea of being an image maker and an image seeker,” Milroy says.

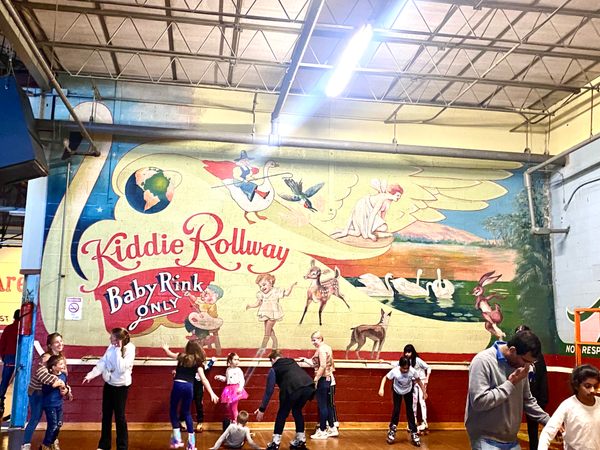

One of the pieces in the show is a new portrait of Milroy’s partner, Lindsay, staring at the viewer with a flock of ducks dive-bombing in the window behind her. Waterfowl are a recurring subject in the work, a nod to Milroy’s Canadian roots. There are other repeating forms: the chalkboards, stacked art books, rubber tree plants, taped-up magazine clippings. Many of these motifs could also function as an inventory of the objects in Milroy’s studio. I feel the slippage between the painted and the real world when I spy a pen knife depicted in several of the paintings sitting on a table’s edge nearby.

After all his decades of studying, I’m curious to know which artists Milroy appreciates today. David Hockney is at the top of his list. What Milroy admires most is the boldness with which Hockney returns to some of art’s most historical disciplines (landscape, portraiture, still-life) and still finds space for progress. To illustrate his point, Milroy holds out his paint-speckled fingers, almost pinching them, and says: “If you can just do something this much different, that’s going to look like a mountain at the end of the day.”

.jpg)