Australia’s Dazzling Native Ingredients

This article is adapted from the February 8, 2025, edition of Gastro Obscura’s Favorite Things newsletter. You can sign up here. Seven to 10 percent of all species on Earth are native to Australia, and more than 80 percent of Australian plants and mammals are not found in nature anywhere else. Yet there’s only one native Australian species widely used for food outside the country: the macadamia nut. When I visited Australia for the first time last month, I was pleasantly surprised at the ease with which I could find food made with native ingredients. Shops in major cities like Sydney and Perth carry Kunzea chocolate bars, bush tomato chutney, and Davidson plum–infused gin. Midden, the restaurant inside the Sydney Opera House, features native ingredients in every dish on their menu (this ended up being one of my favorite meals of the trip). I even bought dried Australian spices to experiment with at home and share with friends. But I couldn’t help but wonder why, aside from the macadamia, the rest of the world hasn’t caught on to what Australians call “bushfood” or “bush tucker.” European colonization of the Americas in the 16th century sparked the Columbian Exchange, the global dispersal of American food plants and animals through trade. You might expect there to be a second round of this phenomenon after Europeans reached Australia, especially given the island continent’s incredible biodiversity. But this hypothetical Aussie Exchange just didn’t take place. One reason Australia’s native foods never spread far is that, before modern air travel, sheer distance made perishable goods difficult to exchange. In the late 18th century, sailing from England to North America took about one month, but the first fleet of permanent English settlers to Australia took eight months to arrive there in 1788. My 20 hours flying from Sydney to New York pales in comparison. There’s also the fact that many native Australian species are ill-suited for domesticity. Even in Australia, kangaroos are hunted, but not farmed. People do farm emus (I once scrambled a domestic emu egg mail-ordered from New Mexico), but the practice is relatively new and far from widespread. Another key factor is that, while Europeans encountered Indigenous agriculture in the Americas that was adaptable to their own methods, the cultivation practices of Aboriginal Australians were unfamiliar. The differences were so stark that Europeans mistakenly believed Aboriginal peoples did not cultivate food at all. But as far back as 6,600 years ago, people in Australia’s southeast established a sophisticated system of channels to farm eels. Others confined wild kangaroos or semi-wild cassowaries (a large flightless bird) for meat. And all Aboriginal Australians practiced sustainable land management, allowing wild resources time to replenish and setting controlled fires to beneficially shape the growth of forest and brushland. The encroachment of European settlers disrupted Aboriginal food systems. In the 1840s, sheep introduced from England almost grazed the radish-like murnong plant to extinction, leading to famine among Aboriginal people for whom it was a staple. Forced assimilation further disconnected Aboriginal people from their traditional foodways. But European-Australians gradually took interest in Australia’s native foods. In the 1890s, Mina Rawson, Australia’s first female cookbook writer, documented her exhaustive experimentation with native ingredients. While Rawson sampled everything from quandong fruit and warrigal greens to roast wombat and ibis, her cookbook makes no mention of the Aboriginal peoples who survived off these resources long before her. In the late 20th century, Australia’s search for a unique culinary identity spurred further enthusiasm for bushfood. A commercial native food plant industry emerged in the 1970s and ’80s, and continues to grow today. The next Aussie crop to become a global star just might be the finger lime, known for the caviar-like pearls inside its fruit, which is now cultivated on a small scale in the United States. But the erasure of Aboriginal Australians from the monetization of native Australian foods continues to be a concern. In 2019, Australian arts and culture magazine Kill Your Darlings reported that “only one percent of the native food dollar value is currently generated by Aboriginal people, whose vast, ancient ecological knowledge makes the industry viable in the first place.” Today, Indigenous Australian chefs and entrepreneurs are helping to reclaim native ingredients and present them in their original context, like Mindy Woods, who broke down a native ingredients starter pack for The Guardian in 2024, and Nornie Bero, author of Mabu Mabu: An Australian Kitchen Cookbook. Some of the native ingredients I purchased in Australia came from Bero’s line of packaged spices, also called Mabu Mabu, which means “Help yourself!” in the Meriam language of the Torres Strait Islands, and is said at

This article is adapted from the February 8, 2025, edition of Gastro Obscura’s Favorite Things newsletter. You can sign up here.

Seven to 10 percent of all species on Earth are native to Australia, and more than 80 percent of Australian plants and mammals are not found in nature anywhere else. Yet there’s only one native Australian species widely used for food outside the country: the macadamia nut.

When I visited Australia for the first time last month, I was pleasantly surprised at the ease with which I could find food made with native ingredients. Shops in major cities like Sydney and Perth carry Kunzea chocolate bars, bush tomato chutney, and Davidson plum–infused gin. Midden, the restaurant inside the Sydney Opera House, features native ingredients in every dish on their menu (this ended up being one of my favorite meals of the trip). I even bought dried Australian spices to experiment with at home and share with friends. But I couldn’t help but wonder why, aside from the macadamia, the rest of the world hasn’t caught on to what Australians call “bushfood” or “bush tucker.”

European colonization of the Americas in the 16th century sparked the Columbian Exchange, the global dispersal of American food plants and animals through trade. You might expect there to be a second round of this phenomenon after Europeans reached Australia, especially given the island continent’s incredible biodiversity. But this hypothetical Aussie Exchange just didn’t take place.

One reason Australia’s native foods never spread far is that, before modern air travel, sheer distance made perishable goods difficult to exchange. In the late 18th century, sailing from England to North America took about one month, but the first fleet of permanent English settlers to Australia took eight months to arrive there in 1788. My 20 hours flying from Sydney to New York pales in comparison.

There’s also the fact that many native Australian species are ill-suited for domesticity. Even in Australia, kangaroos are hunted, but not farmed. People do farm emus (I once scrambled a domestic emu egg mail-ordered from New Mexico), but the practice is relatively new and far from widespread.

Another key factor is that, while Europeans encountered Indigenous agriculture in the Americas that was adaptable to their own methods, the cultivation practices of Aboriginal Australians were unfamiliar. The differences were so stark that Europeans mistakenly believed Aboriginal peoples did not cultivate food at all. But as far back as 6,600 years ago, people in Australia’s southeast established a sophisticated system of channels to farm eels. Others confined wild kangaroos or semi-wild cassowaries (a large flightless bird) for meat. And all Aboriginal Australians practiced sustainable land management, allowing wild resources time to replenish and setting controlled fires to beneficially shape the growth of forest and brushland.

The encroachment of European settlers disrupted Aboriginal food systems. In the 1840s, sheep introduced from England almost grazed the radish-like murnong plant to extinction, leading to famine among Aboriginal people for whom it was a staple. Forced assimilation further disconnected Aboriginal people from their traditional foodways. But European-Australians gradually took interest in Australia’s native foods. In the 1890s, Mina Rawson, Australia’s first female cookbook writer, documented her exhaustive experimentation with native ingredients. While Rawson sampled everything from quandong fruit and warrigal greens to roast wombat and ibis, her cookbook makes no mention of the Aboriginal peoples who survived off these resources long before her.

In the late 20th century, Australia’s search for a unique culinary identity spurred further enthusiasm for bushfood. A commercial native food plant industry emerged in the 1970s and ’80s, and continues to grow today. The next Aussie crop to become a global star just might be the finger lime, known for the caviar-like pearls inside its fruit, which is now cultivated on a small scale in the United States.

But the erasure of Aboriginal Australians from the monetization of native Australian foods continues to be a concern. In 2019, Australian arts and culture magazine Kill Your Darlings reported that “only one percent of the native food dollar value is currently generated by Aboriginal people, whose vast, ancient ecological knowledge makes the industry viable in the first place.”

Today, Indigenous Australian chefs and entrepreneurs are helping to reclaim native ingredients and present them in their original context, like Mindy Woods, who broke down a native ingredients starter pack for The Guardian in 2024, and Nornie Bero, author of Mabu Mabu: An Australian Kitchen Cookbook. Some of the native ingredients I purchased in Australia came from Bero’s line of packaged spices, also called Mabu Mabu, which means “Help yourself!” in the Meriam language of the Torres Strait Islands, and is said at the beginning of a meal.

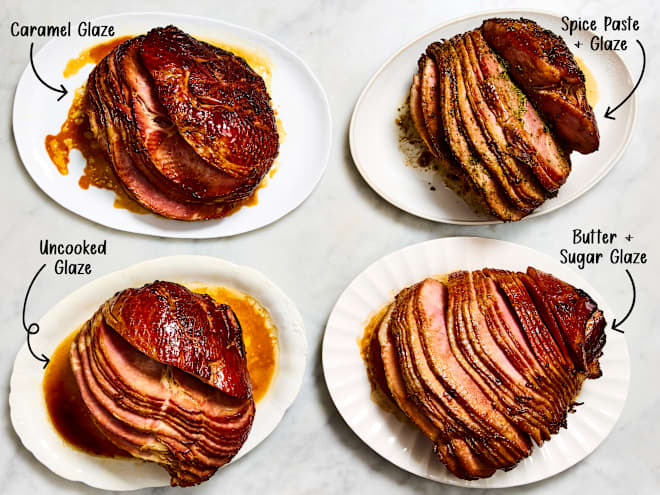

The packaging of my Mabu Mabu spices has suggestions for how to use them, as does an infographic I picked up at the Kalamunda History Village in Western Australia. My meal at Midden provided further inspiration for the elaborate dinner I decided to make using all of my Australian spices, plus whatever ingredients I happened to have on hand. The result was broiled shishito peppers with saltbush; a wattleseed scallion pancake with lemon myrtle dipping sauce; green salad with wattleseed in the dressing; a bean, carrot, and potato stew with native thyme; and anise myrtle bread. But out of all of the things I made, the clear winner was the dessert: strawberry gum panna cotta.

Describing Australia’s native ingredients can be a challenge. Wattleseed reminds me of both poppy seed and sesame; saltbush really is naturally salty, as well as bitter and herbaceous. Even when the ingredient is named in English after a non-native taste-alike, the resemblance to the namesake can be a distant one. Lemon myrtle is aromatic like lemongrass but not tart like lemon; native thyme is more woodsy and earthy than thyme. I find that strawberry gum tastes more like a strawberry candy or soft drink than the actual fruit (it’s also not the chewing type of gum, but the leaf of a eucalyptus or “gum tree”).

Not heading to Australia anytime soon? Strawberry gum can be ordered from online vendors, and a drop of artificial strawberry flavoring will give you a sense of its flavor and aroma: fruity, delicate, and totally unique.