Could New Border Restrictions Literally Tear the Haskell Free Library Apart?

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. Kevin Sexton: Alright, I’m standing in Stanstead, Quebec. I’m a few feet away from Vermont. I live in Canada, and I recently made a trip to the U.S. border. The first thing I was struck by is that this particular border is just open. No fence or anything. There’s a sidewalk in front of me, there are some cinder blocks, and surprisingly I don’t see any border guards, I don’t see any law enforcement. I drove here to see a community library. It’s nice, a two-story brick and stone building with an opera house upstairs. But there wouldn’t be much reason for me to come here at all if it wasn’t for the unique circumstances of where the library is built. It sits right on the border of two small towns in two different countries, Stanstead, Quebec and Derby Line, Vermont. And for over 120 years, it’s been serving both communities. As I stand a few feet from the invisible border, I read an old weathered plaque. “Thanks to an understanding with the border authorities, Canadian visitors are permitted to access the building on foot without having to first report to U.S. Customs. Please remain at all times on the sidewalk and return to Canadian soil immediately following your visit. Thank you for your collaboration.” That’s referring to the sidewalk right in front of me heading into Vermont, to the library’s front door. But there’s also a new sign, “Haskell Library Cardholders Only. All others will be arrested and face prosecution and/or removal from the United States.” And then there’s a big Do Not Enter sign. So I’m not going to cross over the border here. So instead, I follow a path around the back of the building, through the grass, along some carpets thrown down to form a makeshift path to a modified emergency exit. I walk through a room that looks like a fire escape until I find myself not at a reception desk, but deep in the stacks, face to face with a shelf of large print French language books. It wasn’t always this way. There was a time just months ago when I could have used the front door. But then this little library got caught in the crossfire of a much bigger struggle. I’m Kevin Sexton, and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Today, I’ll take you inside this little library that’s been a symbol of friendship between nations for over a century. What happened when the U.S. government decided maybe they don’t want to be friends? This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. Kevin: Inside the Haskell Free Library and Opera House looks like the type of quaint historic building you stop by in a small town on a road trip. There’s a big oak reception desk with a moose head mounted on the wall. There are stained glass windows, pressed steel ceilings, various cases of old knick-knacks, and paintings of men with impressive beards and an older woman dressed all in black with a book in her hand. You can tell they care about their history. In fact, it’s registered as a historic location in both the U.S. and Canada. But aside from all that, it’s just a small community library. Near the desk, there are new releases in both English and French. A few people are browsing around. I meet up with a retired school teacher from Vermont named Kathy Converse, who gives tours at the library. Kathy Converse: I’m a volunteer. I have been a volunteer here for longer than all of the employees put together. Kevin: Right away, I notice another man with a notepad, asking questions to a local. I’m not the only journalist here, I see. Kathy: No, this gentleman is from France. We have had visitors from all over the world. Yesterday was the Netherlands. Today, France. Literally all over the world. Kevin: Kathy shows me around for a bit, before we get to the main attraction: a big black line running diagonally across the floor where the border is. Kathy: So we go from Canada to the U.S. Kevin: Can you describe that? Kathy: It’s a piece of black duct tape, about two inches wide. And so this bathroom is in the U.S. Not that it makes any difference, but that—see the tape? So, the children’s room is half in the U.S. and half in Canada. Kevin: This comes with some complications. Later on in our tour, Kathy points out some flaking paint on the floor of the opera house. Kathy: You see there’s paint off on the floor. And to touch it up on this side, we would have to get permission from the Canadian Historical Society or the Quebec Historical Society. To touch up paint on this side of the line, we have to get permission from the Vermont Historical Society. Kevin: You can cross the border freely in here. I’m allowed to use the bathroom in the U.S. or cross to the American side of the children’s section. I can go anywhere the Americans can go. We just h

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Kevin Sexton: Alright, I’m standing in Stanstead, Quebec. I’m a few feet away from Vermont. I live in Canada, and I recently made a trip to the U.S. border. The first thing I was struck by is that this particular border is just open. No fence or anything. There’s a sidewalk in front of me, there are some cinder blocks, and surprisingly I don’t see any border guards, I don’t see any law enforcement. I drove here to see a community library. It’s nice, a two-story brick and stone building with an opera house upstairs. But there wouldn’t be much reason for me to come here at all if it wasn’t for the unique circumstances of where the library is built. It sits right on the border of two small towns in two different countries, Stanstead, Quebec and Derby Line, Vermont. And for over 120 years, it’s been serving both communities.

As I stand a few feet from the invisible border, I read an old weathered plaque. “Thanks to an understanding with the border authorities, Canadian visitors are permitted to access the building on foot without having to first report to U.S. Customs. Please remain at all times on the sidewalk and return to Canadian soil immediately following your visit. Thank you for your collaboration.” That’s referring to the sidewalk right in front of me heading into Vermont, to the library’s front door. But there’s also a new sign, “Haskell Library Cardholders Only. All others will be arrested and face prosecution and/or removal from the United States.” And then there’s a big Do Not Enter sign. So I’m not going to cross over the border here. So instead, I follow a path around the back of the building, through the grass, along some carpets thrown down to form a makeshift path to a modified emergency exit. I walk through a room that looks like a fire escape until I find myself not at a reception desk, but deep in the stacks, face to face with a shelf of large print French language books. It wasn’t always this way. There was a time just months ago when I could have used the front door. But then this little library got caught in the crossfire of a much bigger struggle.

I’m Kevin Sexton, and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Today, I’ll take you inside this little library that’s been a symbol of friendship between nations for over a century. What happened when the U.S. government decided maybe they don’t want to be friends?

This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Kevin: Inside the Haskell Free Library and Opera House looks like the type of quaint historic building you stop by in a small town on a road trip. There’s a big oak reception desk with a moose head mounted on the wall. There are stained glass windows, pressed steel ceilings, various cases of old knick-knacks, and paintings of men with impressive beards and an older woman dressed all in black with a book in her hand. You can tell they care about their history. In fact, it’s registered as a historic location in both the U.S. and Canada. But aside from all that, it’s just a small community library. Near the desk, there are new releases in both English and French. A few people are browsing around. I meet up with a retired school teacher from Vermont named Kathy Converse, who gives tours at the library.

Kathy Converse: I’m a volunteer. I have been a volunteer here for longer than all of the employees put together.

Kevin: Right away, I notice another man with a notepad, asking questions to a local. I’m not the only journalist here, I see.

Kathy: No, this gentleman is from France. We have had visitors from all over the world. Yesterday was the Netherlands. Today, France. Literally all over the world.

Kevin: Kathy shows me around for a bit, before we get to the main attraction: a big black line running diagonally across the floor where the border is.

Kathy: So we go from Canada to the U.S.

Kevin: Can you describe that?

Kathy: It’s a piece of black duct tape, about two inches wide. And so this bathroom is in the U.S. Not that it makes any difference, but that—see the tape? So, the children’s room is half in the U.S. and half in Canada.

Kevin: This comes with some complications. Later on in our tour, Kathy points out some flaking paint on the floor of the opera house.

Kathy: You see there’s paint off on the floor. And to touch it up on this side, we would have to get permission from the Canadian Historical Society or the Quebec Historical Society. To touch up paint on this side of the line, we have to get permission from the Vermont Historical Society.

Kevin: You can cross the border freely in here. I’m allowed to use the bathroom in the U.S. or cross to the American side of the children’s section. I can go anywhere the Americans can go. We just have to use different doors.

Kathy: So this is our Canadian door. Are you going out?

French Journalist: Oui, j’y vais.

Kevin: The French journalist is leaving. He came from Montreal, so he needs to use the back entrance like me.

French Journalist: Merci beaucoup et bon courage.

Kathy: So he can go out this door, but I cannot.

Kevin: Okay, and I have to.

Kathy: And you have to.

Kevin: And you know how I said I was surprised that no one was watching the border? Well, I was wrong.

Kathy: In the rocks, you can see the birdhouse. That is a camera, a Border Patrol camera, on us, on this door.

Kevin: There are signs throughout the building reminding you to leave the way you came, but the border agents are watching to make sure. So how exactly did this place end up here? It turns out it was no accident. It was built on the border on purpose. It was created by Martha Haskell, the widow of a rich businessman.

Kathy: Martha was a wealthy lady, and she would have musicales in her home. She had a library of her own, and she would share this with her friends. So at one point, she just had the money and had this built.

Kevin: Martha was born in Quebec, and her husband was from Vermont. In their time, the villages on both sides of the border functioned as a single community. Residents would freely shop on either side. Americans and Canadians went to the same churches. That was still the case when they started building the library in 1901.

Kathy: Martha wanted it to serve both communities, so it was intentionally built here. And then when the border was closed, we were grandfathered.

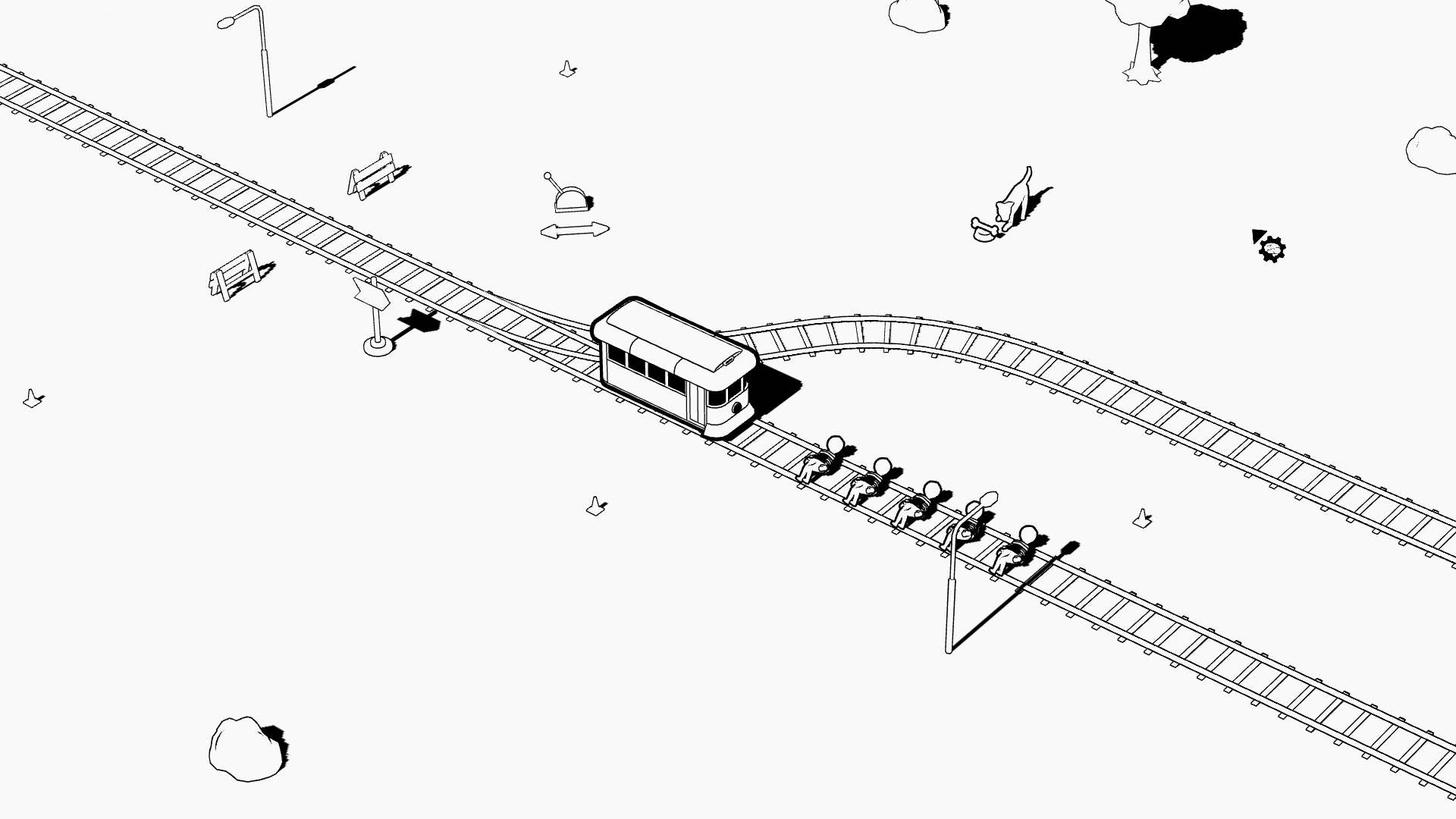

Kevin: The building opened in 1904, just two years before Martha died. Shortly after that, border restrictions tightened, and by 1910, no new construction was allowed on the borderline. The library made some changes over the years. What used to be a men’s reading room is now the children’s area. The women’s room became office space. While books used to be only in English, they started stocking French books as more French speakers moved to the region. But throughout, they kept up their fundamental principles of serving both communities and being a symbol of friendship across the border. They embraced their in-between-ness. Staff come from both countries. They take both dollars at par. They advertise movie nights, where the movie is projected from one country into another. It even became known as a place for Americans and Canadians to get together if they’re having visa issues, which they stress is not permitted. That thick, black piece of duct tape is a symbol of how arbitrary the border is. You could step over it, nothing will happen. And until recently, any Canadians who were visiting could walk along the sidewalk into Vermont and go through the library’s front door. But things started changing in recent years.

Kathy: We’ve always had our Canadian clientele just coming, walking across, and going back. That’s never been an issue. After 9/11, there were, you know, a lot of changes. And then it only got worse with COVID. And then it got even worse after there was an incident on I-91, where a border patrol agent was killed.

Kevin: That happened nearby, about 20 miles south of the Stanstead border crossing. An American border patrol agent pulled over a car to do a visa check on a German national. The people in the car were armed and connected to a violent group in the U.S. There was a shootout, and the agent, as well as one of the passengers, were killed. This was January, the day after Donald Trump’s second inauguration.

Kathy: And it’s gotten even more challenging. And the U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security, Kristi Noem, came to visit us.

Kevin: She came to visit the grieving family of the border guard and dropped in on the library while she was in the area. Library staff only found out she was coming a few hours ahead of time. They say they don’t normally allow political events, but they let Noem come to show good faith. Kathy was here that day.

Kathy: There was an entourage of about 15. The black vehicles were parked up all the way down in the front on the U.S. side. There were two, I think they were state troopers, posted at the door. And they just came in, and they stayed on the U.S. side of the line at first. Sylvie, a chair of our board, spoke with Kristi Noem, and then I was asked to do the tour of the place.

Kevin: While she was there, Kristi Noem stood on the American side of the border and said, “USA number one.” Then she stepped over the line and said, “the 51st state,” the term Trump uses when he talks about annexing Canada. She did this a few times.

Kathy: It was intimidating, especially for our—I’m U.S., but a lot of our young people are Canadian. And I’m an old lady, and they’re in their 20s and stuff. So, I just sort of took it as it was, but I could see in their faces that it was very intimidating. And it was, I think, intended to be.

Kevin: A little while later, in March, American authorities announced they were closing Canadian access to the library. People coming from Canada would have to cross at the official border crossing, with a few exceptions. Canadian library card holders could keep using the sidewalk to the front door until October. Then it would close to them too. This was a period of high tension between the two countries, just weeks after President Trump imposed major tariffs on Canada, and Canada imposed tariffs back. In the community, pushback was loud. Stanstead’s mayor said the towns on either side of the border are friends forever, and that won’t be changed by one man. A Vermont senator called the move troubling. The Quebec member of parliament said the changes make no sense. But U.S. border officials disagree. They say they need to crack down. The Department of Homeland Security later pointed to a bunch of illicit activity surrounding the library. And there was an incident back in 2011 when a man used the building to smuggle handguns into Canada. Still, the president of the library’s board, herself a former Canadian border agent, says that type of thing is rare, and that they work closely with authorities in both countries to keep the border secure. The library was quick to come up with a solution to accommodate their Canadian visitors. They modified the emergency exit to create a temporary entrance for Canadians. That’s where I came in. And they launched a GoFundMe to raise money for a new, permanent Canadian entrance. On the page, they say, “We refuse to let a border divide what history has built together.” At the time I’m recording this, they’ve raised almost $200,000 in donations—double their initial goal. $50,000 of that came from the popular Canadian mystery author, Louise Penny, who cancelled some U.S. tour dates and will end her book tour at the library instead. But plenty of regular people pitched in too.

Kathy: Ninety percent of them are from people across the U.S. who are … almost some of them are angry, and others are just … want to support us because we’re a library. And they’re just sending what they can afford, and little notes of conflation and of support. It’s really special.

Kevin: So I asked Kathy, has there been a positive side to all of the attention?

Kathy: Absolutely not. I mean, we’re a library. We’re a community library. This brought notoriety, but that doesn’t bring anything positive to the communities. So it’s just something we’re going through, and it probably won’t get better.

Kevin: Before I go, Kathy pauses to read me a quote on the wall behind the desk. It comes from the inscription on Shakespeare’s tombstone.

Kathy: “Good friend, for Jesus’ sake, forbear to dig the dust enclosed here. Blessed be the man who spares these stones, and cursed be they who moves my bones.” How’s that for an ending?

Kevin: “Blessed be the man who spares these stones, and cursed be they who moves my bones.” I believe that’s librarian-speak for “Leave us the hell alone.” As I’m getting ready to leave, a French-Canadian man is checking out at the front desk. He grabs his books, takes a few steps toward the front door, then catches himself. He turns and walks toward the back. I follow.

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Our podcast is a co-production of Atlas Obscura and Stitcher Studios. The people who make our show include Dylan Thuris, Doug Baldinger, Chris Naka, Kameel Stanley, Johanna Mayer, Manolo Morales, Amanda McGowan, Alexa Lim, Casey Holford, and Luz Fleming.

Our theme music is by Sam Tindall. Please give us a good review and rating wherever you get your podcasts, and make sure to follow us so you don’t miss a thing. I’m Kevin Sexton, your friend in Canada.

The parking’s on the U.S. side, so I have to walk around through town, down to the municipal parking, down the block. Past small churches and houses. Near the bridge. I’m a little nervous, I’m a little worried. This is Quebec, okay.

.jpg)

![From Chandelier to Cube: The Versatile Forms of 6:AM’s “▢ [quadrato]” Collection](https://image-cdn.hypb.st/https%3A%2F%2Fhypebeast.com%2Fimage%2F2025%2F06%2F12%2F6am-quadrato-new-lighting-collection-two-fold-silence-exhibition-milano-design-week-2025-tw.jpg?w=1080&cbr=1&q=90&fit=max)