Meet the Volunteers Who Keep Thru-Hikers Moving

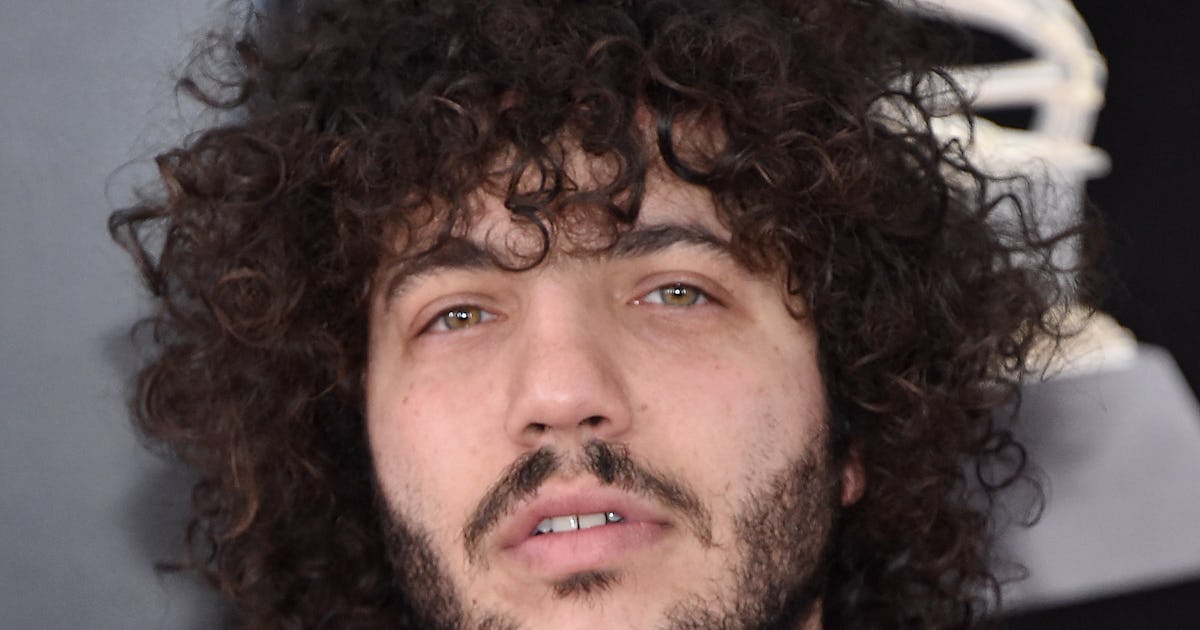

In 2023, Ashley Lynn Neville was hiking the Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail with her husband and their daughter, pushing big miles to reach Oregon’s Cascade Locks in time for Pacific Crest Trail Days: an annual outdoor festival that caters to thru-hikers. The trio was still a day or two out from the city and their spirits were high, but the fatigue was real. As they approached a road junction near Lolo Pass, just past the trail’s mile marker 2117, they noticed a propped-up piece of brown cardboard with the words “Trail Magic” written across it in bold, black Sharpie. And beside it: a canopy tent, a circle of camp chairs, and a low fire where a tall, bearded man was grilling hot dogs for any weary hikers who came his way. “Packs were dropped. Shoes came off,” Neville says. “It was a moment of grace.” The tall, bearded man was what’s known as a “trail angel.” These self-appointed volunteers offer unexpected acts of kindness and generosity to hikers along long-distance trails, including the 2,653-mile-long Pacific Crest Trail or “PCT,” which runs along the Pacific Coast from the U.S.–Mexico border to the U.S.–Canada border, traversing desert, forests, national parklands, and mountain passes along the way. Participants in the informal trail angel network are often motivated by personal aspirations, connecting with others, and even motherly instincts—similar to strangers cheering on marathon participants from the sidelines or travel enthusiasts offering their couches to young globetrotters coming through. Some offer hikers rides to and from town, while others will greet them at trailheads with everything from slices of fresh watermelon to pancake breakfasts and make-your-own taco bars. Paying a hiker’s tab at a local restaurant, providing a place for a hot shower, even performing trail maintenance are some of the many forms of trail magic that trail angels perform. Ani Benson, an office manager from Bellevue, Washington, first got interested in becoming a trail angel around her 50th birthday, when she was looking for a way to celebrate outdoors. “I’m a hiker,” she says, “but I’ve never done anything like the PCT. I’m just so fascinated by it.” She learned about trail angels through YouTube videos and various friends. “I thought that would be cool to do.” Benson got her first opportunity to work trail magic several years later, when Carolyn “Ravensong” Burkhart—who became the first woman to solo thru-hike the PCT in 1976 and is now the proprietor of the Lion’s Den, a hiker hostel in the tiny community of Mazama, Washington—put out a call for drivers over Labor Day weekend. “I wasn’t doing anything,” Benson says, “so I wrote back and said, ‘I can be there around lunchtime.’” She drove four hours north from Bellevue, picked up a group of hikers, and drove them another four or so hours south to Sea-Tac Airport while talking the whole time. Since then she’s continued to provide transport to hikers and help them gather their resupplies, including food, water, medication, and gear. “It satisfies the mom instinct in me, to want to take care of people,” she says. Benson describes one October afternoon after a heavy rain storm, when she’d been at the Lion’s Den helping to shut things down for the season. A hunter pulled up with two women hikers in his truck, both of them soaked to the bone. “They looked like drowned rats and were wearing garbage bags to try and stay dry,” she says. Benson immediately went into mom mode. “‘OK,’ I said, ‘get your butts in here.’” She handed them some extra clothes that the hostel keeps handy—flannel pajama pants and Hawaiian shirts—and urged them to take a hot shower before getting changed. In true trail angel fashion, she washed their wet clothes and made sure the hikers were properly cared for and ready before they returned to the trail. Former commercial fisherman Scott Maloy knew nothing about the PCT before his then 18-year-old daughter decided to thru-hike it several years ago. “I had a lot of apprehension about it,” he says, “but the more I learned about the trail the more psyched I got and wanted to help.” His first foray into trail magic came between Mount San Jacinto and Big Bear Lake in southern California’s San Bernardino National Forest. Maloy flew down from Washington, where he’s based, rented a four-wheel drive Jeep, and stopped at both Costco and Walmart to load an empty cooler with steak, lobster, strawberries, fresh whipped cream, ground beef, and bagels. He set it all up in a rented cabin equipped with a shower, washer, and dryer, then hiked in to meet his daughter and her “trail family.” Once back at the cabin, they feasted. “We had steak and lobster, strawberry shortcake, and even lobster bagels for breakfast one morning,” he says. Maloy’s magic also included condiment packets that can add a lot of flavor to bland camping food, replacement lids for reusable water bottles, and extra chargers that he set up in his Jeep for hikers to re-up their battery-p

In 2023, Ashley Lynn Neville was hiking the Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail with her husband and their daughter, pushing big miles to reach Oregon’s Cascade Locks in time for Pacific Crest Trail Days: an annual outdoor festival that caters to thru-hikers. The trio was still a day or two out from the city and their spirits were high, but the fatigue was real.

As they approached a road junction near Lolo Pass, just past the trail’s mile marker 2117, they noticed a propped-up piece of brown cardboard with the words “Trail Magic” written across it in bold, black Sharpie. And beside it: a canopy tent, a circle of camp chairs, and a low fire where a tall, bearded man was grilling hot dogs for any weary hikers who came his way.

“Packs were dropped. Shoes came off,” Neville says. “It was a moment of grace.”

The tall, bearded man was what’s known as a “trail angel.” These self-appointed volunteers offer unexpected acts of kindness and generosity to hikers along long-distance trails, including the 2,653-mile-long Pacific Crest Trail or “PCT,” which runs along the Pacific Coast from the U.S.–Mexico border to the U.S.–Canada border, traversing desert, forests, national parklands, and mountain passes along the way.

Participants in the informal trail angel network are often motivated by personal aspirations, connecting with others, and even motherly instincts—similar to strangers cheering on marathon participants from the sidelines or travel enthusiasts offering their couches to young globetrotters coming through. Some offer hikers rides to and from town, while others will greet them at trailheads with everything from slices of fresh watermelon to pancake breakfasts and make-your-own taco bars. Paying a hiker’s tab at a local restaurant, providing a place for a hot shower, even performing trail maintenance are some of the many forms of trail magic that trail angels perform.

Ani Benson, an office manager from Bellevue, Washington, first got interested in becoming a trail angel around her 50th birthday, when she was looking for a way to celebrate outdoors. “I’m a hiker,” she says, “but I’ve never done anything like the PCT. I’m just so fascinated by it.” She learned about trail angels through YouTube videos and various friends. “I thought that would be cool to do.”

Benson got her first opportunity to work trail magic several years later, when Carolyn “Ravensong” Burkhart—who became the first woman to solo thru-hike the PCT in 1976 and is now the proprietor of the Lion’s Den, a hiker hostel in the tiny community of Mazama, Washington—put out a call for drivers over Labor Day weekend. “I wasn’t doing anything,” Benson says, “so I wrote back and said, ‘I can be there around lunchtime.’” She drove four hours north from Bellevue, picked up a group of hikers, and drove them another four or so hours south to Sea-Tac Airport while talking the whole time. Since then she’s continued to provide transport to hikers and help them gather their resupplies, including food, water, medication, and gear.

“It satisfies the mom instinct in me, to want to take care of people,” she says.

Benson describes one October afternoon after a heavy rain storm, when she’d been at the Lion’s Den helping to shut things down for the season. A hunter pulled up with two women hikers in his truck, both of them soaked to the bone. “They looked like drowned rats and were wearing garbage bags to try and stay dry,” she says. Benson immediately went into mom mode. “‘OK,’ I said, ‘get your butts in here.’” She handed them some extra clothes that the hostel keeps handy—flannel pajama pants and Hawaiian shirts—and urged them to take a hot shower before getting changed. In true trail angel fashion, she washed their wet clothes and made sure the hikers were properly cared for and ready before they returned to the trail.

Former commercial fisherman Scott Maloy knew nothing about the PCT before his then 18-year-old daughter decided to thru-hike it several years ago. “I had a lot of apprehension about it,” he says, “but the more I learned about the trail the more psyched I got and wanted to help.” His first foray into trail magic came between Mount San Jacinto and Big Bear Lake in southern California’s San Bernardino National Forest. Maloy flew down from Washington, where he’s based, rented a four-wheel drive Jeep, and stopped at both Costco and Walmart to load an empty cooler with steak, lobster, strawberries, fresh whipped cream, ground beef, and bagels.

He set it all up in a rented cabin equipped with a shower, washer, and dryer, then hiked in to meet his daughter and her “trail family.” Once back at the cabin, they feasted. “We had steak and lobster, strawberry shortcake, and even lobster bagels for breakfast one morning,” he says. Maloy’s magic also included condiment packets that can add a lot of flavor to bland camping food, replacement lids for reusable water bottles, and extra chargers that he set up in his Jeep for hikers to re-up their battery-powered devices.

Some of the thru-hikers stayed overnight while others just paused their treks for an hour or two, but once Maloy’s daughter was back on her way, he realized he wasn’t yet ready to go. “I thought to myself, ‘I’ve got all this stuff and I’m already here,’” he says. “‘I might as well stay a little longer.’” He stuck around, treating some thru-hikers to his remaining food and taking others to pick up their resupplies. “I just admire what they’re doing and want to help them—it’s such a cool thing.”

In some cases TAs will take gas money or payment for food, though the purest form of being a trail angel is offering assistance without expecting anything in exchange.

“Obviously there’s a position of privilege to being able to have that flexibility and time and resources to be able to do that,” says a trail angel who goes by her initials, M.E.G.. “For me, I feel like I can.” M.E.G., who lives in central Washington and works from home, had been reading books on the PCT and found a few area Facebook groups that mentioned trail angels. It was the perfect fit. “I do a little bit of hiking,” she says, “but I prefer to help out more.”

Like many trail angels, M.E.G. likes to be a part of the action without becoming the main event. Around 2014, she signed up with the hospitality exchange service CouchSurfing to connect with strangers traveling through the Pacific Northwest. “At the time I wasn’t able to offer them a place to stay,” M.E.G. says, “but I would pick them up from the airport, take them around, and give them a tour of [the town] where I was living at the time.”

These days, M.E.G. and her husband sometimes offer thru-hikers a place to stay and a home-cooked meal, as well as an occasional ride or some baked goods. “Just something as simple as a muffin means so much to them,” she says. They once hosted a thru-hiking German couple for an entire week because one of them had sustained a leg injury. A year or two later, M.E.G. and her husband went over to Hamburg to visit them. “The trail has definitely led to a lot of great connections.”

But as welcoming as trail magic is for many PCT thru-hikers, it can be overdone. After all, solitude is what attracts many thru-hikers in the first place. The Pacific Crest Trail Association, a self-proclaimed “eclectic band of trail junkies” that’s been committed to protecting, maintaining, and advocating for the PCT since 1977, recommends keeping any sort of trail magic gathering small, and reminds trail angels to never leave food and drink (which can attract wild animals and create trash) unattended. Trail magic also makes the biggest impact where hikers need it most: away from major highways and in less traveled sections of the trail, such as central California’s Sierra mountain range.

Not every hiker sees the magic in trail angels (according to a August 30, 2016, Outside article, “The question of whether trail angels, posted in droves along the country’s most popular trails, degrade the wilderness experience is a legitimate one”), and there have undoubtedly been bad experiences when it comes to angels and hikers alike. But according to both M.E.G. and Neville (who’s since become a trail angel herself), those encounters are few and far between. Instead, the trail angels are a tight-knit community that finds joy and solace in what the hikers are doing, while satisfying some personal incentives of their own.

“In Western culture, independence and self-sufficiency are often seen as the ultimate goals, but the trail shows you that being self-sufficient doesn’t mean going it alone,” Neville says. “Being at the mercy of the weather, terrain, and your body ... the kindness of others becomes not just helpful, but sacred. Trail angels are such a profound part of that.”

Plan your next adventure with our Explorer’s Guide to the National Parks, packed with overlooked wonders, expert tips, and all the best spots to visit.

![How to Tame Pets in Rune Slayer – Full Pet List [TUNDRA & BEACH EXPANSION]](https://www.destructoid.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/rune-slayer-how-to-tame-all-pets.png?quality=75)

.jpg)

![From Chandelier to Cube: The Versatile Forms of 6:AM’s “▢ [quadrato]” Collection](https://image-cdn.hypb.st/https%3A%2F%2Fhypebeast.com%2Fimage%2F2025%2F06%2F12%2F6am-quadrato-new-lighting-collection-two-fold-silence-exhibition-milano-design-week-2025-tw.jpg?w=1080&cbr=1&q=90&fit=max)