David Cronenberg’s movie conspiracies never lead anywhere — and that’s the point

The Shrouds, the latest movie from horror legend David Cronenberg, certainly asks more questions than it answers. At the heart of it, funerary-tech entrepreneur Karsh (Vincent Cassel) is dealing with some sort of conspiracy — he’s just not sure what. See, Karsh is a widower who’s not quite ready to let his dearly departed wife go […]

The Shrouds, the latest movie from horror legend David Cronenberg, certainly asks more questions than it answers. At the heart of it, funerary-tech entrepreneur Karsh (Vincent Cassel) is dealing with some sort of conspiracy — he’s just not sure what.

See, Karsh is a widower who’s not quite ready to let his dearly departed wife go — in that she’s buried in his futuristic cemetery right next to where he’s dining with his blind date. Karsh owns GraveTech, a company that allows mourners to monitor dead loved ones in their graves, watching over them as they go quietly into that gentle decay. But thanks to the high-resolution 4K cameras his state-of-the-art burial shrouds provide, he’s noticed strange, microscopic growths on his wife’s bones.

Their appearance prompts him to hunt down exactly what is happening with his wife’s body — are the growths a byproduct of the device she’s buried in? A latent effect of her experimental cancer treatments? A secret third thing? And does it have anything to do with why his graveyard got vandalized in the middle of the night?

The answer to all these questions is far more byzantine and mysterious than he might expect. And in true Cronenbergian fashion, the answer is far squishier than it should be, winding through nearly every obsession Cronenberg has had in his long, illustrious career, including microscopic abnormalities in bones and bodies, technology that pulls at the fabric of early adoption, and conspiracies so vast that they seem to transcend humanity and understanding.

[Ed. note: This post discusses the events in The Shrouds in full detail, along with glancing end spoilers for other Cronenberg movies. Read on only if you’re comfortable confronting the unknown (in the form of spoilers).]

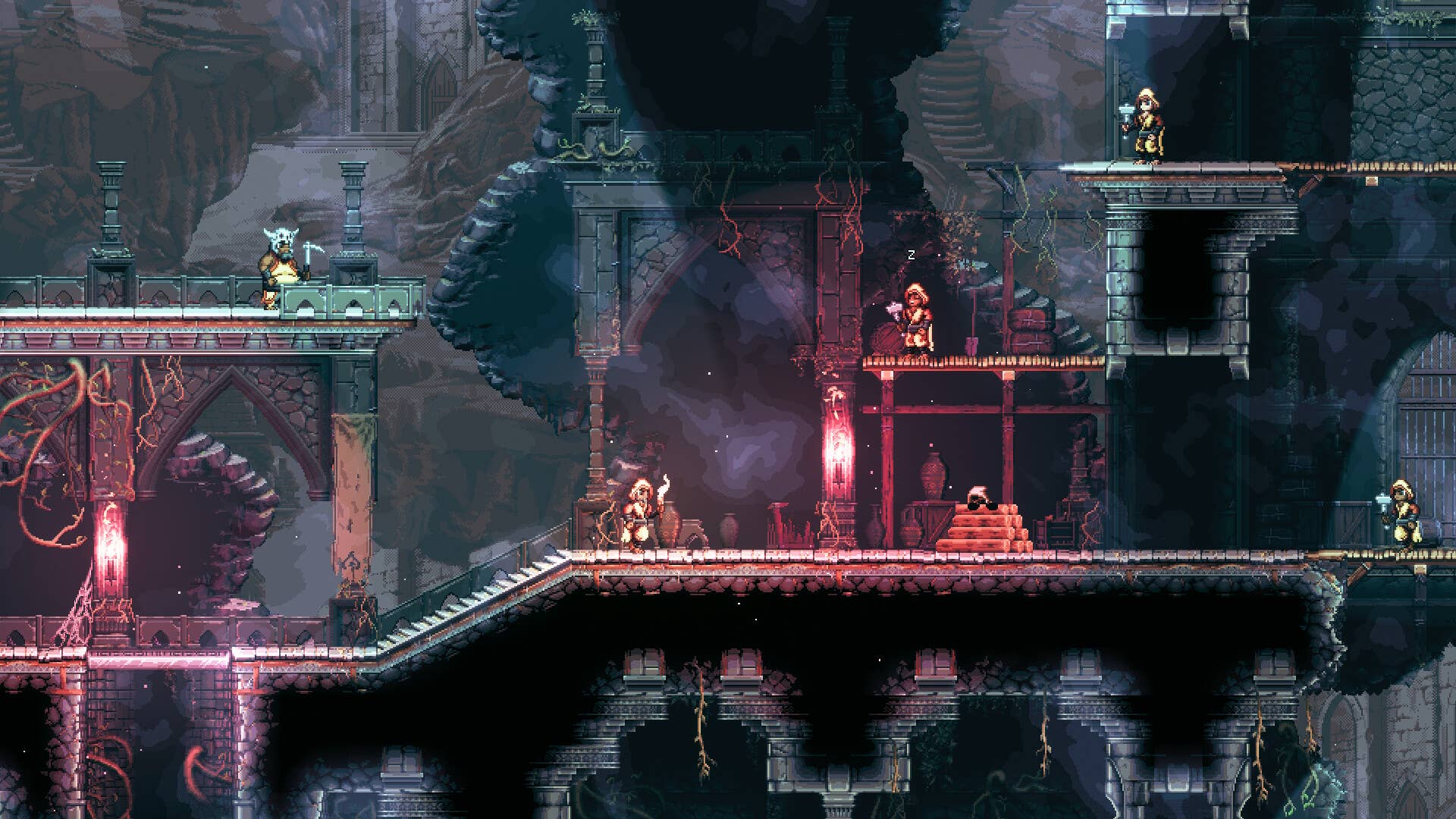

Cronenberg often moves through concepts the way other people might parse a family tree — tracing from one central point, then uncovering whole worlds and lived realities just a few steps away. His lead characters find new subcultures that aren’t hidden so much as they’re waiting just beyond the scope of everyday life — like in Crash, where a group of car-crash enthusiasts dare each other to find the purest sexual rush, or in Crimes of the Future, with an underground circuit of body modifiers pushing the limits of their organs in the name of art. Within these hidden worlds are lethal broadcast signals and psychics who can blow up other people’s heads — but often, there’s some sort of greater machination at play.

And yet, just as frequently, conspiracy in his filmography leads nowhere major. His movies aren’t triumphant action thrillers where heroes bring down corrupt systems, they’re labyrinths that spit victims out weathered from their experiences, if they aren’t simply swallowed whole. They have been changed, sometimes profoundly, but it’s sort of beside the point; the world goes on as it was.

The circuitous nature of these journeys Cronenberg’s protagonists go on are the point: In Crimes of the Future, a plastic-eating child represents the next stage of human evolution, the way to save us all from climate change. But by the end of Crimes, the child has been murdered, and his abilities covered up. That seems to point to a deeper conclusion for the film, on how those in power might encourage even the most transgressive art and entertainment, so long as it doesn’t upset the status quo. In Crash, James and his wife start the movie by seeking meaningful sex in a sort of alternate dispassionate Toronto. But after all their sexual adventures, they wind up once again coming together to find sex that makes them feel something real amid the cold highways around them. Cronenberg’s films use the self-containment of story as a means to stand the audience at the doorway of bigger concepts and let them peer in.

His willingness to engage with complex questions without feeling the need to answer them is what makes his movies so indelible and foresightful. As Cronenberg plumbs big ideas, he’s experimental and playful rather than cautionary and careful. And as a result, his films feel freer than their contemporaries, and more prescient in hindsight: It’s tempting to look at eXistenZ’s focus on video games and say it’s calling out a single industry and the overblown fears about what games do to players’ psyches. But (particularly a conspiracy almost totally in service of a final line, which makes it unclear whether anything in the movie up to that point even matters) Cronenberg sets the film’s scope more around bigger ideas of technology, and the way any outlet in life changes people’s relationship to the world around them. However you affect your body — games, sex, psychotherapy, late-night television — you are altering your reality.

You don’t have to hit The Shrouds with a tuning fork to see that it’s also singing in the same key of fruitless conspiracy. New cabals seem to sprout everywhere Karsh looks; each scene has a new character who might be secretly working against him, each with their own spin on the evidence he’s poring over.

It’s possible to chart out the possibilities by the end of The Shrouds: Karsh’s graveyard-based mesh network is viable, hackable tech. Several groups want in on the business for different reasons as GraveTech starts to expand globally; several key figures in his life have already had their hands on it, and they may or may not have ulterior motives. But that isn’t what all this conspiracy is for in the story. To understand what it is for, you have to understand the yearning.

The sense of longing in The Shrouds is palpable from the very beginning. Karsh is not subtle about his lingering love for his dead wife, Becca (Diane Kruger). Nor is Cronenberg subtle about his own connections to Karsh: In 2017, Carolyn, his wife of more than four decades, died of cancer. In the ensuing years, he’s repeatedly expressed what that loss was like for him. During the release for Crimes of the Future, he said that at one point, he felt he might never make films again, and that The Shrouds was born out of his processing.

This is both a big admission and a somewhat expected one. Autobiography is not new ground for Cronenberg, though he’s been resistant to any one-to-one readings of his work. Which tracks — Cronenberg wrote 1979’s The Brood following his own acrimonious divorce from his first wife, but one certainly couldn’t say that his ex-wife started growing homicidal children in her external wombs thanks to the healing power of psychoplasmics.

Instead, he makes his flair for autobiographical inspiration more dynamic by introducing his protagonists to schemes and realities, then pulling them through those underworlds. The archetypal Cronenbergian hero doesn’t get called to the journey so much as they trip into it. The worlds they wind up in find a logical fiction that flows from issues of the moment in kaleidoscopic ways.

The echoes of Cronenberg’s personal experiences are just as important as the way real-life news and technological developments reverberate through those same halls of possibility: His 1983 cult classic Videodrome feels in line with Marshall McLuhan’s ideas around the dangers of television, particularly as cable TV was peaking. But Cronenberg based the story on his own childhood experiences of worrying he might see something disturbing when his TV picked up late-night American broadcast signals. Like Karsh mentions in The Shrouds, Cronenberg felt a visceral urge to join his wife in her casket when he saw it being lowered into the ground. But here, as in Videodrome, public events and the director’s private impulses merge to create something twisted and new.

And as ever, Cronenberg is happy to twist our recognition of either. As The Shrouds opens, Karsh dreams of watching his wife’s body underground, and he screams in agony at their separation. He wakes up mid-dental exam, with his dentist warning him that grief is rotting his teeth, and offering Becca’s dental records to help Karsh through his grieving process.

That’s a perverse, strange offer — and it’s funny, in the offbeat, deadpan sort of way that’s Cronenberg’s specialty. But it’s also the perfect lens for considering The Shrouds: His melancholy is reshaping his world. Becca is long gone, but he longs for her physical form all the same. In her absence, the question looms over everything in his life: What is worth conserving?

We see Karsh’s grief take many forms throughout The Shrouds as he tries to gain some distance and control over his life and work. In the three years since Becca died, he’s moved, leaned on an AI program called Hunny to organize his life, and gone all in on the Japanese aesthetic, complete with an in-apartment koi pond.

And it’s not hard to see how GraveTech and his monitoring of Becca’s final resting spot is an extension of his attempts at control. When mysterious vandals sabotage GraveTech’s cemetery, including Becca’s grave, Karsh’s brother-in-law Maury (Guy Pearce) likens it to Becca being taken away from her husband. Karsh brags that his shroud feed allows him to be “involved with her body the way I was in life, only even more.” He doesn’t care that his energy alarms and turns other people off; he even takes a date to the cemetery to see Becca. His need to preserve her is the focal point of his life.

But that desire keeps getting complicated by outside events: sabotage to her GraveTech headstone, the bone growths, the nagging questions about what her doctor/ex-boyfriend was really doing to Becca in her final days — anything, really, that suggests that for all Karsh’s love and devotion, he didn’t know Becca as fully as he wanted to, and he’ll never have the chance to improve that, as much as he wishes to.

A theme that runs through much of Cronenberg’s work is a warped version of seeking connection — think one scanner psychically calling out to another in Scanners to bloody ends, or Seth Brundle in The Fly wanting to use his teleporter to merge with his lover Veronica so they can evolve together as a single fly-person. The Shrouds doesn’t share the same stomach-churning body-horror tendencies as these two films, but it gets at the same thoughts all the same, through Karsh’s casting about for meaning. It’s not enough to have lived and loved with Becca; he wants to share everything with her, even her decay.

And the film often evokes these twisted forms of connection with the same preternatural Cronenbergian cool that laces through all his films. In real life, from the outside, grief advances through your life like a benign cancer, sometimes presenting to others as stoicism as it advances. But in truth, grief — like paranoia — is built on heightened emotion that gets sublimated and settled into something calm and organized. It operates at a depth: It’s hard to communicate how much it imposes on your everyday life. There’s a human reality buried beneath the grammar and translation.

Conspiracy thrillers are usually built on the same lifeblood of deceptive calm. As a genre, they bring a coherence to the utter madness of paranoia and subterfuge, as forces greater than someone press down on them, totally altering their worldviews.

The Shrouds constantly plays with the ways grief and paranoid thrillers are at once at odds with and deeply wedded to each other. In the world of this movie, passion and disconnection go hand in hand, and nonchalance belies a more frenzied inner state. And even in its funniest or uncanniest moments, it still feels like a better mirror of modern, online life than anything Black Mirror or Missing have to offer. Karsh sees the bone growths for himself — or maybe he doesn’t. He works with a team he can trust, but his trust quickly erodes depending on who he’s talking to, and whether he should be factoring in their nationality and allegiances. Everything he experiences is at once the gospel truth and also a total myth.

My guess is this, as with so many of Cronenberg’s other works, will give the conversation around The Shrouds and its meaning a longer tail than it might seem to have on first blush. And a big part of that is because in the end, all the conspiracy goes absolutely nowhere.

Catharsis in Cronenberg’s work is never neat, and his endings are the best reflection of that dynamic. Even the most straightforward finales come with an intense echo of irresolution. Veronica in The Fly kills Brundlefly, who even begs for death, and she’s left bereft with her ex, who has lost a hand and foot to acid. Videodrome’s Max Renn succumbs to the brain tumors transmitted by broadcast signal. Dead Ringers’ Mantle twins died as they lived: with only each other.

As Cronenberg told David Breskin in his 1992 book Inner Views: “If we are to have optimism we have to be very tough, we have to be very tough in our understanding of what reality is and what life’s possibilities are, and we have to create our optimism of that.” Within his stories, breaking through to the emotion at the end — however hard that becomes — helps cut “through the fog to the reality” of the situation.

In that way, what makes the autobiographical nature of The Shrouds so interesting isn’t the way Cassel is styled to look like Cronenberg himself. It’s the way Karsh feels so unclear on what to do with himself with his wife gone. In interviews, the younger Cronenberg of the ’90s was brash and optimistic, talking openly about how he wanted to someday die on set or routinely pondering his own mortality. Ahead of The Shrouds, Cronenberg’s familiar opinionated voice is still there, but tempered by age and experience. There’s a sense that the younger Cronenberg only thought about confronting his own death; maybe he always thought he’d go first.

Thus The Shrouds splashes around in the deep end of a lonely pool, the frustration of loving, longing for, and feeling left behind by a partner who’s passed on. Karsh gets caught up in conspiracies because conspiracy theories are just another strategy to cope, a titillating way to intellectualize his pain and give meaning to the profound absence he’s facing.

For the first few decades he was making films, Cronenberg’s protagonists were forced through transformations in service of tracing the story out. They were often people already on the precipice of some great change — an emotional breakthrough, recognizing the evil around them, or acknowledging their true desires. And they give into the seductive quality of letting go of what they were and becoming something new. But for the last quarter-decade or so, the blueprint has been different. Cosmopolis’ central billionaire is frozen in the question of whether his would-be assassin will pull the trigger. Crimes of the Future’s Saul Tenser gets the movie’s whole plot explained to him, and simply retreats to see what he can do about it.

With The Shrouds, Cronenberg spends his time letting Karsh chase down the mystery of what really happened to his wife, and what prompted her strange growths. Was it the Chinese? The Russians? The shroud? The bone cancer? The doctor? He hopes to “solve” the mystery of her death and finally resolve the loss for himself. But then her body is effectively gone, and all he’s left with is all he had in the first place: his grief. And so the movie simply lets Karsh be “worn down.” In the face of his endless questioning for meaning, with theories flying everywhere, Karsh is left with no choice but to fly away.

Cronenberg is one of many legacy directors whose name has been turned into an adjective: “Cronenbergian,” used to describe things that feel of a spirit with his penchant for body horror. And yet his work has always been so much more meaningful than that, as The Shrouds demonstrates, and maybe the term derived from his name should be too. His horror is always in service of something greater, built not just from body mass, but from dream fog and news detritus — the “conceptual gloop,” as he referred to it in Cronenberg on Cronenberg.

The Shrouds’ final scene brings everything home as a short, bittersweet Cronenbergian reminder: Karsh will carry Becca wherever he goes, and see her in every woman he beds. He will never truly be without all she brought to his life. His new lady has all of Becca’s scars and missing limbs, and it’s not exactly clear which of them is speaking to him when they lean in for a kiss. The image is a bit freakish — but what about love and life isn’t?

The Shrouds is playing in theaters now.

/33901f8b-dab8-4ac5-8d01-7bf897aa6a96--2015-0122_chocolate-dump-it-cake_james-ransom_008.jpg?#)

.jpg)