How to see lucha libre – Mexican wrestling – in Mexico City

Get to know lucha libre – the much-loved spectacle of Mexican wrestling – with this guide to seeing it in Mexico City.

"Ladies and gentlemen, this match will be contested under best two out of three falls, with no time limit!" is the rallying cry that fires up the crowd in their green and orange plastic seats at Arena México in Mexico City’s gritty, working-class Doctores neighborhood. Children fidget eagerly in anticipation as their parents take a big gulp of a spicy michelada (beer and tomato juice or beer with chili and lime) and whistle wildly. Most die-hard fans have been attending lucha libre (wrestling) shows since childhood, excitedly tagging along with their parents.

On stage, a masked wrestler in dark clothes – likely a Rudo or villain – steps through the ropes and is announced over the loudspeaker as the crowd starts to heckle. Minutes later, a second luchador (wrestler) appears – this time, kids perk up and the crowd starts cheering. This is a Técnico – the hero – and usually the crowd favorite.

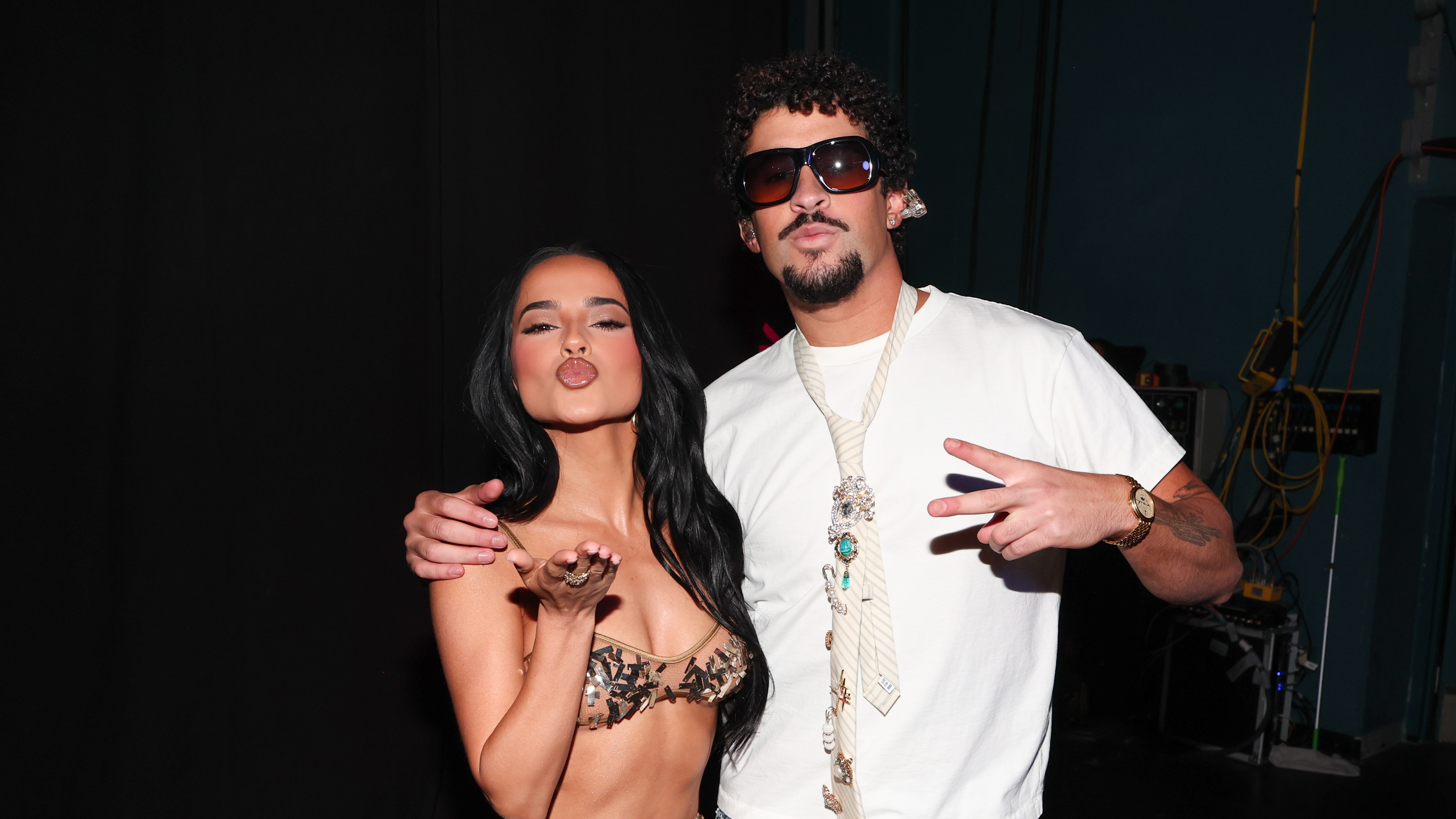

The night advances and luchadores of all stripes take their turn in the ring, sometimes in groups of three against three, and often involving skilled female bodybuilder-types who have yet to headline a show. Little people, known as Minis, and luchadores in drag, nicknamed Exóticos, also make an appearance, blowing kisses as the crowd erupts in laughter and cheers – a stark reminder that lucha libre is not exactly politically correct.

Both an over-the-top theatrical display teetering on kitsch and an iconic part of Mexican culture, lucha libre is a cathartic, must-do experience for any visitor looking to soak up the energy of the Mexican capital. Here’s everything you need to know before diving in.

History of lucha libre

Lucha libre isn’t just one of Mexico’s biggest sports, it’s a full-blown spectacle. Second only to soccer in popularity, it’s been a staple of Mexican culture for nearly a century. In fact, in 2018 it was even declared an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Mexico City and, shortly after, the Senate made September 21 National Lucha Libre and Mexican Professional Wrestler Day.

Its origins can be traced back to the French Intervention (1863–1867), when exhibitions of Olympic and Greco-Roman wrestling were held in the country. But lucha libre as we know it today didn’t arrive until 1933, when a local tax official named Salvador Lutteroth González brought the sport home after watching exhibitions in El Paso, Texas. With the goal of training Mexican wrestlers, he founded the world's oldest active professional wrestling promotion – the Empresa Mexicana de Lucha Libre (EMLL), now known as the Consejo Mundial de Lucha Libre (CMLL) – and repurposed a boxing arena, Arena Modelo, for lucha libre.

As the sport grew in popularity, so did the need for bigger venues. In 1943, Lutteroth helped bring Arena Coliseo to life – a larger, circular-shaped arena designed specifically for wrestling events. His most ambitious project came in 1956, when he replaced Arena Modelo with a brand-new venue: Arena México. Dubbed "the Cathedral of lucha libre", it remains the sport’s most important stage. Safe to say, he earned his title as the father of Mexican wrestling.

The 1950s were the golden age of lucha libre, with some of the sport’s most famous figures suddenly becoming TV and movie stars. Overnight, fans could watch their favorites – legends like El Santo and Blue Demon – battling it out right in their living rooms.

What to know about lucha libre

Rudos vs Técnicos: Epic battles between villains and heroes are waged at every lucha libre match. In one corner of the ring, Técnicos represent virtue. They fight fair and with honor. Usually clad in bright colors, they’ve historically been fan favorites and are enthusiastically greeted by roaring crowds. Rudos, on the other hand, are villains who have no qualms about fighting dirty – going as far as attempting to rip Técnicos’ masks off even if it means instant disqualification. Dressed in darker colors, they’re constantly booed by the audience – although some particularly charming Rudos have been known to gain the crowd’s favor by becoming beloved antiheroes, as is the case with Perro Aguayo Jr.

High-flying vs grappling styles: Olympic wrestling, Greco-Roman wrestling, judo and jiu-jitsu were some of the disciplines that influenced lucha libre. Wrestlers tend to fall into two main wrestling styles: high-flying (aéreo) and grappling (a ras de lona). The contrast between these styles makes matches more dynamic, with Técnicos often favoring aerial maneuvers and Rudos relying more on grappling and brute force.

High-flyers dazzle the crowd with gravity-defying moves like the Tope Suicida, a headfirst dive through the ropes, or the Moonsault, a breathtaking backflip off the top turnbuckle. Grapplers, on the other hand, use technique and power to wear down opponents with moves like La Campana, a painful submission hold, or the Suplex, a powerful slam that sends opponents crashing to the mat.

Storylines and rivalries: Some feuds last for years, creating legendary rivalries between characters. The biggest one in lucha libre history centers on pop culture icons Rodolfo Guzmán Huerta, better known as El Santo, and Alejandro Muñoz Moreno, aka Blue Demon. El Santo was the first Técnico legend – a true superhero. He took his fights beyond the ring, battling vampires, werewolves and criminals on the silver screen.

While Blue Demon was initially the underdog, he proved himself a worthy rival after defeating El Santo multiple times in the early 1950s, cementing his reputation as a legend in his own right. Despite their rivalry in wrestling, they sometimes teamed up in movies, though their dynamic was always tense. Films like Santo y Blue Demon vs los Monstruos showed them as reluctant allies, sometimes bickering but ultimately working together.

El Santo remained the most beloved luchador and never lost his mask. He retired in 1982 and passed away in 1984, revealing his face only once before he died. Blue Demon retired in 1989 and passed away in 2000, respected as one of the few luchadores to defeat El Santo multiple times.

What do the masks mean?

Wrestlers wear a mask to protect their identity, and losing one is a huge deal. In the early days, masks were much simpler – usually a single color to help identify the wrestler. These days, they’re far more elaborate, multi-hued and can represent anything from animals to gods and mythological creatures.

The mask has come to be the most recognizable symbol of lucha libre and is a luchador’s most-prized possession, allowing them to adopt an alternate persona – one that can even turn into legend.

But not all wrestlers wear a mask. In their absence, wrestlers often bet their hair, having to shave it off if they lose. When a wrestler bets their mask or hair, it means they’ve reached a defining moment in their career, putting their identity and everything that has made them iconic on the line.

Audience participation

Ask any Mexican and they’ll tell you one of the main reasons to attend a lucha libre match is to blow off steam. Cheering and chanting are encouraged, while booing – and even tossing drinks when things get heated – aren’t unheard of. Don’t be alarmed if you see audience members hurling insults at a luchador or the referee, or small children making rude gestures to signal their frustration – it’s all in good fun.

A spirited atmosphere is evidence of a fun night out, so pick a side and show your appreciation! That said, things can get heated sitting ringside, so choose a seat further back if you’d rather avoid the chaos up front.

Where to see a show

Arena México

Nicknamed the "Cathedral of lucha libre", Arena México is the largest and most famous venue to enjoy this iconic sports spectacle. With a seating capacity of 16,500, this legendary arena in Colonia Doctores has hosted Mexico’s biggest wrestling events since 1956. It’s not far from trendy Roma and Condesa, but the neighborhood is considered rough around the edges, so it’s best not to venture too far after the show – order a rideshare instead of walking.

Arena Coliseo

Located in the historic center near Tepito, Arena Coliseo has an old-school charm that die-hard fans love. Its compact, circular shape offers a more intimate but equally rowdy lucha libre experience. The atmosphere can get intense, and the surrounding streets aren’t the safest at night, so this one is best tackled by joining a tour.

How to score tickets

You can buy tickets at the door, but for popular events, it’s best to purchase in advance through official sellers like Ticketmaster or the CMLL website. Some hostels and tour operators offer lucha libre experiences with guides. Tours cost around US$80 and include a stop for beer and mezcal, pre-lucha tacos and your ticket to the show. Sometimes, they’ll throw in a mask and a luchador meet and greet for photo ops.

What to expect at the show

As you approach the arena, you’ll see rows of street vendors selling colorful masks for you to wear at the show. Once at the door, security will scan your ticket and wave you through, and you’ll find yourself surrounded by food stalls with everything from tacos and tortas (sandwiches) to popcorn, chips, beer and micheladas. Don’t fret if you’re short on time to grab a snack – vendors circulate constantly, so you’ll have another chance to fill up at your seat.

If you’re expecting the violence of boxing, that’s not what you’ll find at lucha libre. There’s a code between luchadores; they challenge each other but the goal isn’t to hurt – it’s to entertain. Lucha libre is a simulation of sorts, where visually arresting moves are more important than drawing blood from an opponent. And while there certainly was blood in the early days, you don’t see much of that anymore. But that’s not to say it’s all fake and fighters can’t get hurt – lucha libre moves have grown increasingly complex, and one wrong fall can cause a luchador their career, or their life.

Generally, families, die-hard fans and casual spectators all mix together in a wild but friendly environment.

Make a night of it

Kick off your night of extreme Mexican kitsch at a mezcalería (mezcal bar). El Palenquito is right around the corner in Roma, and serves a wide variety of mezcal, mezcal-based cocktails and snacks – including chapulines (crickets) – in a rustic setting with an exposed tile roof.

If you’ve had enough mezcal on your trip, go for a pulquería instead. Once considered the drink of the gods, this viscous drink made from fermented agave sap can be ordered plain or “cured” in a variety of fruit or nut flavors. La Nuclear in Roma Norte is one of the best places for pulque, but keep in mind it’s about a 25-minute walk from Arena México.

Those who want to remain on an earlier dinner schedule can grab tacos at Cariñito Tacos in Roma. Served on corn husks, tacos here made it into the Michelin guide and are unlike everything else in the city – think Southeast Asian influences like cochinita Thai and Cantonese pork.

Keep the party going

There are no late-night eats that Mexicans enjoy more than tacos. Taquería Orinoco has become famous for its tacos de chicharrón (pork rind), but the long lines at the Roma location can test anyone’s patience. In nearby Juárez, El Huequito serves up a hefty stack of al pastor (spit-cooked marinated meat) with a pile of tortillas on the side for a meal that won’t be easily forgotten.

If you filled up on snacks at the arena and are looking for a livelier plan than tacos, right across from Arena México, La Hija de los Apaches serves its pulque with a side of live music and the occasional drag queen show.

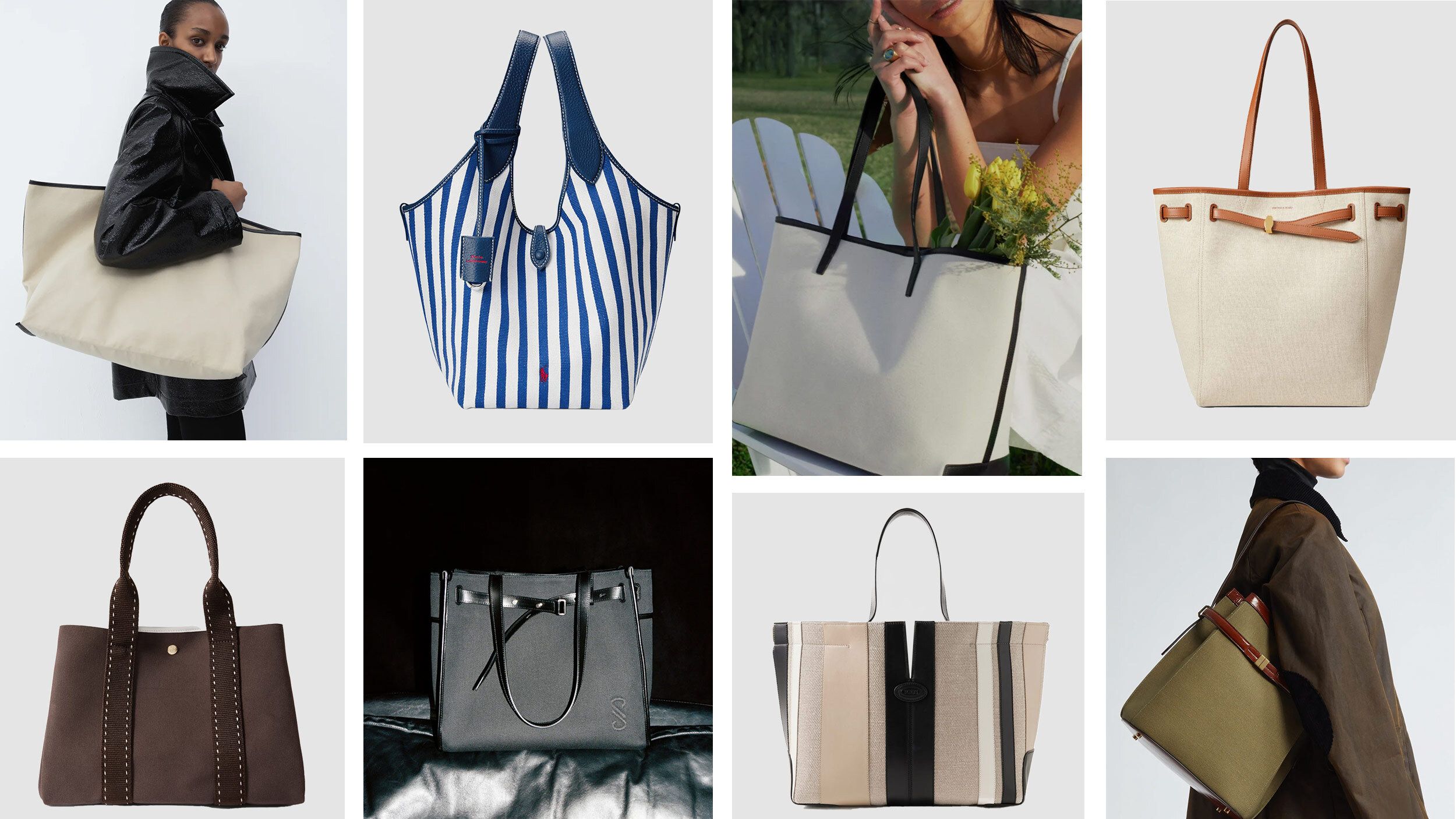

Take it home

Nothing says lucha libre like a mask. Expect to pay M$250–450 (US$12.50–22.50) on average at street stalls, while the official shop inside Arena México sells them for M$500 (US$500). Masks of luchadores like Místico and Atlantis are some of the most popular. Other souvenirs include posters, stickers and action figures.

![Definitive Ghoul://Re Skill Tree Guide [RELEASE]](https://www.destructoid.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/ghoul-re-skill-tree-guide.webp)

![huNter-: "We're playing much better in practice [than officials] because we don't have pressure"](https://img-cdn.hltv.org/gallerypicture/1fIN0ESmRAShnAGE8-AGsD.jpg?auto=compress&ixlib=java-2.1.0&m=/m.png&mw=107&mx=20&my=473&q=75&w=800&s=bed1184795448ccb785e62e470499ddd#)

.jpeg)