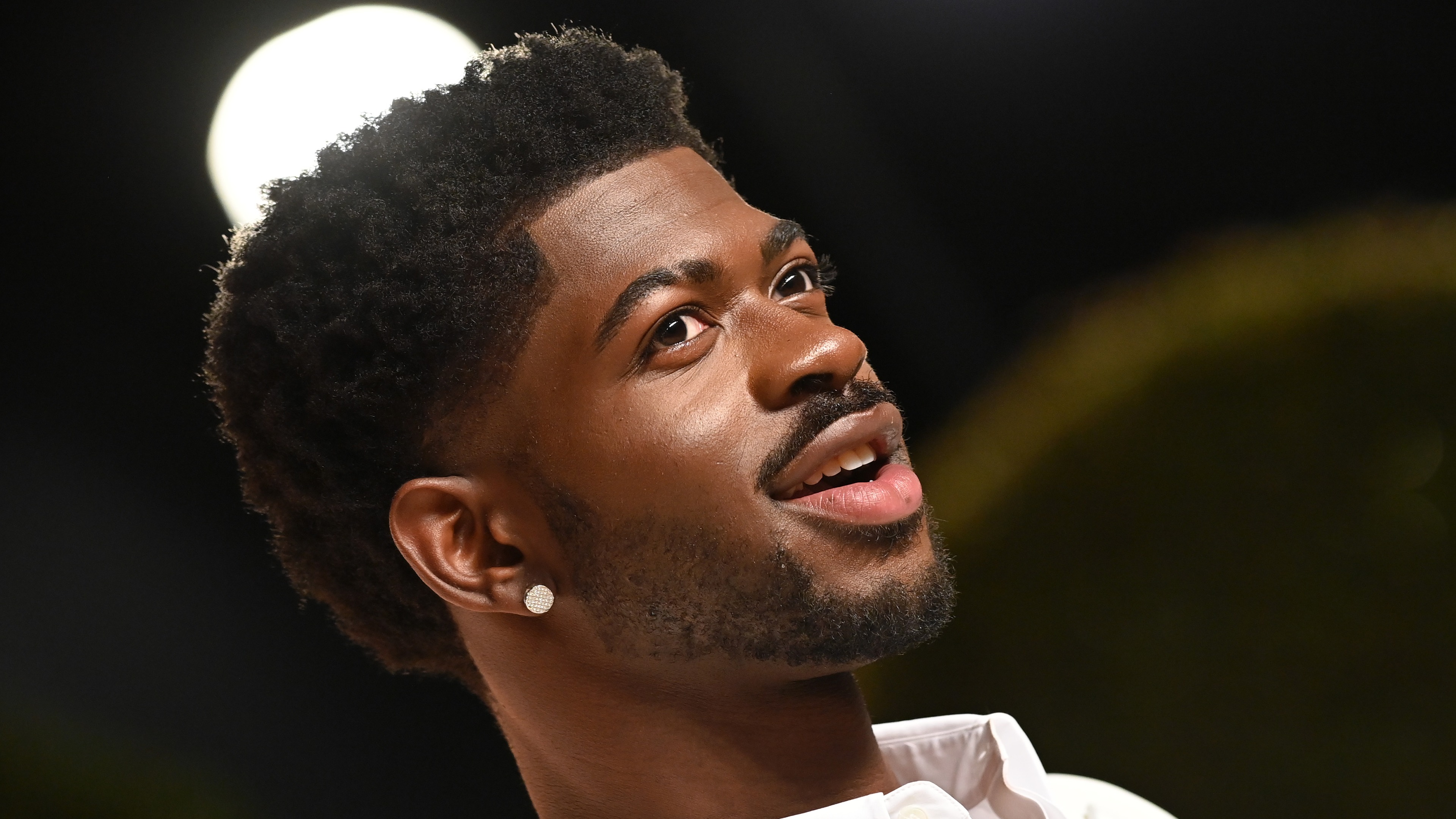

Oz Perkins explains The Monkey’s ‘sophisticated, joyful’ slaughterhouse vibe

Fans of Osgood Perkins’ movies have some idea of what to expect from him at this point — and none of it looks like The Monkey, his gleefully ghoulish new Stephen King adaptation. In the dark, heavily textured projects The Blackcoat’s Daughter, I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House, and Gretel & […]

Fans of Osgood Perkins’ movies have some idea of what to expect from him at this point — and none of it looks like The Monkey, his gleefully ghoulish new Stephen King adaptation. In the dark, heavily textured projects The Blackcoat’s Daughter, I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House, and Gretel & Hansel, Perkins put ghoulish spins on familiar horror creatures: demons, ghosts, and witches, respectively. His 2024 movie Longlegs arguably does the same with serial killers and psychic powers, albeit with a dark sense of humor.

But none of those movies will prepare people for The Monkey’s outright goofy comedy, which turns disemboweling and death by mass hornet ingestion into squirmy laugh moments. Adapting a Stephen King short story about a wind-up toy monkey that haunts a family with a series of deaths, Perkins leans hard into the fragility of human bodies, and how death by elaborate misadventure might be lurking around any corner.

“Everybody dies,” a beleaguered mom (Tatiana Maslany) sighs early in the film, conveying a world-weary philosophy that comes up repeatedly as her now-grown son Hal (Theo James) battles the monkey. Polygon sat down with Perkins to talk about that message, why he veered into comedy for this movie, and why it was important to make the deaths in The Monkey as unbelievable as possible.

This interview has been edited for concision and clarity.

Polygon: The Monkey seems like such a departure from any other movie you’ve ever made. But does it feel that way to you?

Oz Perkins: It does, because the end result is so different from what I think people expect from me. And that’s the best news for me. I think given the opportunity to do my thing now in a more visible way, and having the ability to take a turn and surprise people, that’s really a great joy. And it seems to me that if you’re going to be doing this job, surprise is your friend.

It’s weird, I wrote The Monkey before I wrote Longlegs. It just took longer to come together. And I think that’s important to mention, because it just indicates that it’s just another facet of what I think, how I process, what I like, and what’s meaningful to me. This tonality — the playfulness of a piece of entertainment in the horror space that happens to be reverential to Stephen King, who I think really popularized the enjoyment of horror — it just felt like a good fit to me.

What’s your relationship with Stephen King’s work been like throughout your life?

It started like probably a lot of people’s did: Before I could read one of the books, I was kind of aware of the books. I was aware of my dad’s copy of Pet Sematary, this thick book with the kid’s scrawled handwriting on the cover, the misspelled title, the cat’s face. It was obviously scary, but it was playful-scary. It was like, You’re going to have a good time with this horror.

Horror can be a fun thing. There’s almost a healing quality to it. It’s an uplift. I remember feeling all of those things rushing into me as a kid before I even read any of it. Misery was probably the first Stephen King book I read as a new book, as it was coming out, and it felt like a bit of a challenge — again, funny, sly, and unexpectedly dirty in a way that was really pleasurable.

Did you have any particular connection to “The Monkey” as a story when you were discovering King’s work?

It’s not one that I remember specifically. When I was given the opportunity to adapt it and I read it, it certainly stirred some kind of jingle-jangle in my mind, like, Oh yeah, I kind of know this. But more than anything, I connected to the fact that everybody knows that the monkey’s face is — there’s something wrong with that. There’s something uncanny that creates this unease, this weird revulsion-slash-attraction. So when I knew that was going to be the lead image for this movie, it was exciting.

The Monkey‘s repeated tagline — “Everybody dies” — is presented as maybe a little cathartic, a little bit of a relief, because it’s so absolute and inarguable. But when the characters say it, the tone is cynical, sometimes a little scary, sometimes bitter. It’s a complicated message. How were you hoping people would take it?

It contains all of that. What the mom character has to offer is this sort of salve on existence. “Everybody dies” is a very scary notion, but it’s also fine. As the priest says, it is what it is. It’s not really something to struggle with, because you can’t struggle with it. There’s no struggle to be had. It’s not going to struggle with you. It’s never going to be like, Oh, you know what? We changed our mind. Not everybody dies. Some people are not going to die.

There’s this immovability to it, which demands acceptance. Couched in the language of a horror movie, you’re right — it feels ominous or threatening. But once removed from it, when you’re in the place of surrender and just letting it be the truth, you realize there’s no threat.

It’s really almost the opposite of a threat. It’s just what is. So when I hit on that real, sort of I dare say elegant, neat turn of phrase, and realized that was the tag for the movie — that’s what the movie has to offer. That’s what a horror movie is. That’s what Texas Chain Saw Massacre is, right? Everybody dies. It’s also true in an old-age home. Same fact.

That said, so much of horror is about particularly messy, painful, shocking ways of dying! I certainly hope dying of old age isn’t as awful as being carved up by a chainsaw. How do you get from an elegant statement about accepting inevitability to what happens to pretty much any of the characters in this movie? Certainly these aren’t ways you’d want to die, even if you do accept death as a given.

And none of them are ways in which you can die. So that was the rule of thumb for me. It was like, I had a license to make these deaths as gruesome and as shocking and as horrific and repellent as I wanted — really Itchy and Scratchy [on The Simpsons]. But the idea is that none of them are physically possible, so there’s no threat. There’s no actual palpable threat to any of these things.

Pool water and electricity do not interact that way. Hornets do not fly into your mouth. It doesn’t happen. So that kept it in this realm of playfulness, almost like a circus performance. “Everybody dies” is a somber truth, but The Monkey treats that fact with a cartoon sensibility, which felt like the most sophisticated, joyful way of doing it.

Does making a comedy movie feel like a one-off? Like an experiment? Like the start of a new phase in your career? Do you want to do more movies in this particular vein?

What’s been cool about it, especially juxtaposed with Longlegs, is that now everything I do is a one-off. Now everything I do is going to be one of one. I think if you look at the great directors who you want to emulate — if you look at Stanley Kubrick, for example, every picture is a one of one. And I think if there’s a dream, it’s probably to accomplish that. David Lynch’s movies are all one of one. If you’re looking at those kinds of artists and you’re trying to emulate that kind of impact, it’s a good place to land.

The Monkey is in theaters now.

-Baldur’s-Gate-3-The-Final-Patch---An-Animated-Short-00-03-43.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)