Vivienne Westwood Is the Original Riot Grrrl

With a new Manhattan store, a forthcoming feature-length film, and her storied fashion line, the British fashion icon still maintains an original punk attitude.

Vivienne Westwood practically invented the idea of the concept shop. In 1971, she opened her storefront on 430 Kings Road, London dubbed “Let It Rock.” The boutique was groundbreaking for its time: 1950s rock and roll music was not in fashion and the mainstream was more into hippie culture. In the years that followed, this iconic shop would change its title and aesthetic more than four times and become a landmark of London fashion, as well as a statement of intent from Westwood about rebellion against everything conventional. The most well-known of its iterations is probably “Sex,” which included everything from leather bondage and chains to ripped, provocative t-shirts and plenty of latex. When “Sex” opened, it cemented Westwood’s place in the punk hall of fame and added her to our modern-day directory of political activists in fashion.

Westwood was born in Glossop, Derbyshire in 1941. At the age of 17, she moved to London, where she spent time working as a teacher before beginning a legendary career in fashion. “I’ve always had a political agenda,” she tells me, from her home offices in London. “I’ve used fashion to challenge the status quo.” For Westwood, it’s not a matter of why she’s an inherently political designer, but how she expresses this. “Because of their opposition to the Vietnam War, the hippies politicized my generation,” she says. “I was horrified at the corruption that ran the world. We saw it as a question of youth against age. Who needs leaders who are a total rip-off, who create war and torture?”

This way of thinking inspired Westwood’s interest in the 1950’s and was the genesis of the first generation of her aforementioned shop, which she originally opened with her partner (and the manager of the punk band Sex Pistols), Malcolm McLaren.

But it’s not just that her original boutique, or even her clothing, is political; politics are in the DNA of her runway shows, public statements, and even the way she addresses media—like the time she impersonated Margaret Thatcher on the 1989 cover of Tatler, reportedly wearing an Aquascutum suit Thatcher had ordered and then canceled. Or, for another example, see the bold statement she made when she sent model (and future French First Lady) Carla Bruni down the runway wearing real fur underwear with a matching coat for Fall 1994. Not to mention the moment a waif-like, bare-breasted Kate Moss paraded, her face painted white and her head topped with an aristocratic blue hat, across the Spring 1994 catwalk eating a Magnum ice cream.

Though not innately political, these are the brash concepts and ideas Westwood designed to create the perfect kind of spectacle that would both challenge fashion and encourage conversations. To add a more modern reference, in 2013, the designer wore a Chelsea Manning badge to the Met’s annual ball (she also dedicated a collection to her that year). And just a few months ago, for the label’s menswear show, Westwood presented a two-minute and 45-second film in lieu of the traditional show in which she and her models talk about clothing as a form of empowerment. The theme? War and “Don’t Get Killed,” which also served as the hashtag and title of the video across the social media platforms it was posted on. Moments like these are also the subject of Westwood: Punk, Icon, Activist, a feature-length film by Lorna Tucker to be distributed by Dogwoof (responsible for other famous fashion documentaries like Dior and I and Bill Cunningham New York) in the U.K. and Ireland in March 2018.

"I tried to prove by example that the past is as relevant today as when it was invented, ideas are as relevant today as when they were invented."

“[Malcolm McLaren and I] moved into the back of the shop,” says Westwood, thinking back to the historic location on King’s Road. “Our inspiration went through various stages: Hells Angels, sex and bondage, torn clothes. Every time we changed our collection, we changed the name of the shop. All these elements resolved in punk—where Malcolm’s slogan was ‘Sexual Autonomy for Kids’ and my contribution was a spiky haircut, tribal makeup, and anarchy. The total look was DIY and urban guerrilla.”

Those days of punk and rebellion were the very early moments of the brand. In 1981, Westwood presented her first full collection, with her partner McLaren. Fondly referred to as “The Pirate Collection,” this just might be the most clearly defined moment in which Westwood traded punk aesthetics for punk ideals—and by extension, became even more politically active in nature. “I lost interest in punk,” she says. “I realized subversion is in ideas and ideas come from culture.” That collection contained Westwood’s own takes on historical dress, from which she drew inspiration and then transformed into modern iterations (think baggy, pirate-like trousers and romantic Victorian corsets).

Westwood’s debut collection also took inspiration from Native American aesthetics, in the form of sashes, stiffened felt hats trimmed with leather braiding, and square-toed, flat boots. “I was really attacking the status quo more than ever by this stance,” she says of the collection, which was considered quite a political statement at the time. “The 20th Century was a mistake. It was the age of the iconoclast: ‘History is rubbish, the past is rubbish, all we had to do was follow the latest thing!’ Smash culture and what fills the gap is consumption. I tried to prove by example that the past is as relevant today as when it was invented, ideas are as relevant today as when they were invented—and I proved it by copying historical clothes. No designer had ever done this before, they’d been inspired by historical clothes, but I actually copied them.”

As one of the most important and most referenced British designers in the world, Westwood began to realize that culture—and fashion as something beyond the things we wear—was the missing link. Her Fall 2005 collection, called “Propaganda,” is also one of the collections she considers to be among her most political. “The worst evil of propaganda is non-stop distraction,” she says, speaking on the concept. “This comes in the form of consumption, which includes bombardment by news—lies—and media opinion.

My T-shirts have always had a political message, and I began to put graphics on everything: clothes, bags, shoes, hats.” The collection also included some of the very same historical influences that have made her into a household name, known for making a statement as well as creating divine, beautifully crafted clothing: dresses with constructed bodices and boning, recalling the label’s subtle obsession with the craftsmanship and style of the mid-century. Around this same time, Westwood collaborated with the British civil rights group Liberty on a line of limited edition T-shirts defending habeas corpus, which featured a baby and the slogan, “I am not a terrorist, please don’t arrest me.”

Just over two years ago, Westwood announced she’d be changing the name of her main line from Vivienne Westwood Gold Label to Andreas Kronthaler for Vivienne Westwood. It’s not without reason either: The two—partners in life and fashion despite the 25-year age gap—were married in 1993, the same year she received her OBE and was photographed at the ceremony without underwear. They met while Westwood was teaching a class in Austria.

“I was teaching in Vienna, Andreas had been my pupil and I recognized that as a designer, he was a world-beater,” she recalls. “He came to work with me and tapping into my design helped to pin him down. At this point, Andreas knew so much more about couture than I did.”

Since then, the two have been taking the brand in an even more political direction—but with efforts that focus more than ever on climate change. “We need to reduce and clarify the collections,” she notes of the decision to rename the brand, “so that the amount of clothes we produce can tally with the cheapest possible price. This is what I’m working towards. In order to clarify the collections, Andreas and I divided our work into two distinct lines: ‘Vivienne Westwood’ and ‘Andreas Kronthaler for Vivienne Westwood.’ Clarifying the lines is better for the environment, better for people—it means people can choose, beautifully, what suits them best.”

The duo has also focused on expanding in new ways, in the form of a newly opened three-story flagship store in New York City as well as a colorfully shot New York City campaign by the duo’s friend and frequent collaborator over the years Juergen Teller. “We cast transgender and club kids to wear and model our clothes,” says Kronthaler. The campaign also includes Chloë Sevigny and was photographed at the top of the New York City store, in its exhibition space.

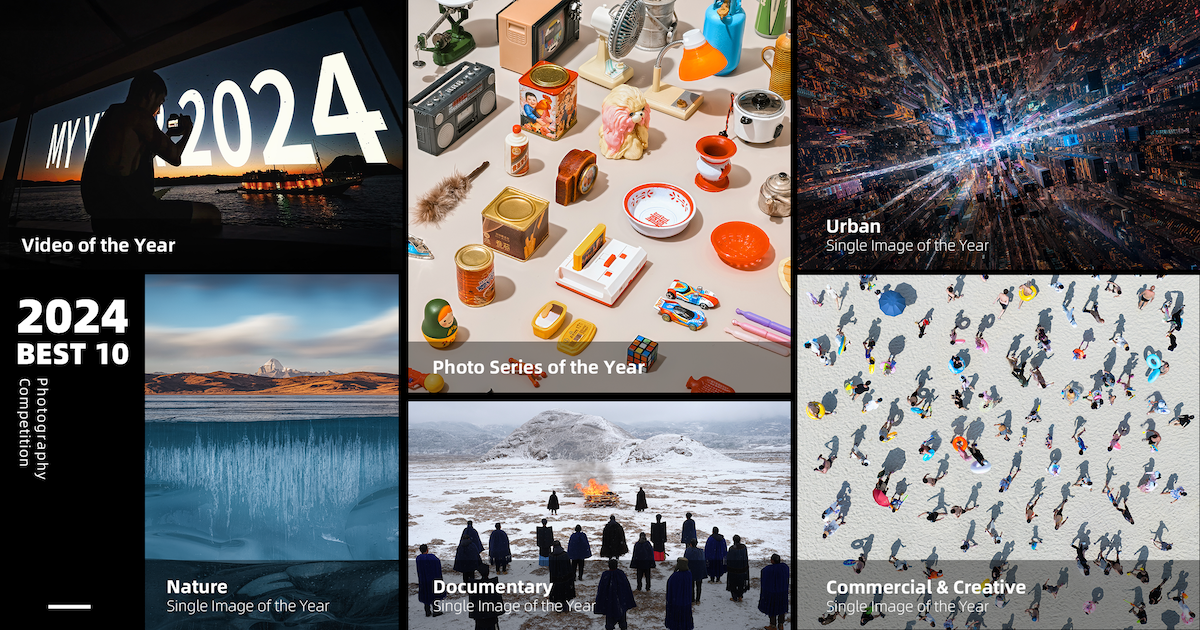

"The best graphic I've ever done is the map...It is based on the geothermal map of NASA."

The inspiration is mutual, too. “When I first met Vivienne, we spent all our time looking at the big couturiers from the beginning of the 20th century,” explains Kronthaler. “We spent a lot of time in the Victoria and Albert Museum and whenever we travelled to New York, Vivienne had a good friend that worked in the Metropolitan Museum of Art archives, so we would spend hours, days, in there studying the beauty of the clothes.”

“Andreas joined me at a time when I had just reworked the 18th century corset, the crinoline, the ultra-high platform shoes, and English tailoring,” Westwood comments. Corsets have since become a hallmark of the label and according to the brand’s website, “Westwood was the first 20th century designer to use the corset in its original form since Poiret had rejected it in 1909.”

“The corset was first invented for little boys to give them stature, and I called it the ‘Stature of Liberty (SoL),’ Westwood relates. “It looks great flat-chested or with your dumplings boiling over. Andreas seized the tailoring to create an ultra-feminine silhouette, an hourglass created with false bums and tits, a foundation of cushions and cages. I was really proud that we had invented a new silhouette for fashion that reiterates the point that ideas can only come from tradition.”

Ideas may come only from tradition, but for now, Westwood is working harder than ever to make her voice heard when it comes to climate change. She has her own website devoted to the cause, which is updated frequently (http://climaterevolution.co.uk/). “Politics and climate change are one and the same thing,” she explains. Her latest project is called “Vivienne’s Playing Cards.” Cards illustrated by Westwood herself—like the Ten of Clubs or Five of Hearts—each have their own page on her website, accompanied by a video explaining specific climate change issues narrated by Westwood. (Sometimes the illustration will end up on a T-shirt, too.)

Since 2015, the designer has also been a vocal supporter of the Green Party of England and Wales. In addition, in 2014, she became an ambassador and investor for Trillion Fund, which uses crowdfunding to finance solar and wind energy projects around the world. At about the same time, she launched a campaign backed by George Clooney and singers Chris Martin and Paloma Faith to promote Greenpeace’s work to save the Arctic.

So, what comes next for a designer so heavily steeped in political activism? “What I want now,” she says, “is a sustainable fashion business. The definition of that is not just a question of no plastic; what the designer wants is beautiful clothes at the right price. Buy less, choose well, make it last.”

CAPTION FOR MAP: “The best graphic I’ve ever done is this map,” says Westwood. “It is based on the geothermal map of NASA.”

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)