Why the Maître d' Is Still the Ultimate Power Player in Fine Dining

Five of the world's best restaurant gurus—from Polo Bar and Sunset Tower to Contramar and Scott’s—reveal the tricks of the trade.

From 1941 to 1972, Le Pavillon was the Manhattan restaurant for families like the Kennedys and the Astors. While the famed French hot spot cycled through many head chefs, the maître d’, Henri Soulé, was a constant. Hailing from the French coastal city of Bayonne, Soulé was tiny (five feet five), well-groomed, and impeccably dressed. As the gatekeeper of New York’s scene-iest restaurant, he accrued great power. He found Harry Cohn, the cofounder and then president of Columbia Pictures, vulgar. Soulé sat him at terrible tables, way in the back of the dining room, even though Cohn owned the building. When Cohn raised the rent as revenge, Soulé simply relocated to the Ritz Tower, on 57th Street—the ultimate chess move. Diners followed Soulé without hesitation.

Maître d’s are the maestros of a nightly concert that takes place in the best dining rooms. The name is short for “maître d’hôtel,” a title that dates back to the 16th century, when it referred to men who ran mansions. Today it’s technically defined as someone who oversees the reception and seating of guests in a restaurant, but the job is much more than that. It requires charisma, charm, and the ability to communicate with the chef and their team while supervising waiters and welcoming guests. The hours are long, and the outlandish requests from needy celebrities, foodie nerds, and customers with bad attitudes never stop.

Starting around the late 1950s, dining out became a sport and a form of entertainment. Getting a table—let alone a good one—at a buzzy restaurant became a way to telegraph one’s status. See: American Psycho, Bret Easton Ellis’s classic novel satirizing 1980s greed and vanity. The ultimate embarrassment for Patrick Bateman, the status-conscious protagonist, is his inability to secure a reservation at New York’s hottest restaurant. Getting laughed at by the maître d’ leaves him “stunned, feverish, feeling empty.” He heals his bruised ego by doing 150 push-ups and committing murder.

Sirio Maccioni, the enthusiastic ringmaster of Le Cirque, the now shuttered Upper East Side institution, turned the job into an art form. Because of him, the French restaurant—whose regulars included everyone from Roy Cohn and Frank Sinatra to Nancy Reagan and Betsy Bloomingdale—hummed day and night in Reagan-era Manhattan. Maccioni’s talent lay in his ability to be a “trusted adviser, fixer, and social gatekeeper,” as The New York Times put it. Or, as gossip columnist Liz Smith described him, “he doesn’t want to be one of his clients, yet he is the closest a lot of them have to a friend or shrink.”

Since the early 2000s, celebrity chefs have taken over as the faces and voices of restaurants. Even so, there are five eateries around the globe with maître d’s carrying on Maccioni’s legacy. Contramar, in Mexico City, is known for its long, casual lunches, where artists and locals linger for hours. Weekends see it packed with fans, including Salma Hayek Pinault and Gwyneth Paltrow, who snack on the famous tuna tostadas and drink mezcal. In London, Scott’s is old-school Mayfair: impeccably prepared seafood, white tablecloths, men in suits. Tower Bar, in West Hollywood’s Sunset Tower Hotel, is about seeing and being seen while rubbing elbows with Oscar winners and power agents. Manhattan’s Polo Bar epitomizes American glamour with its dark wood paneling, ice-cold martinis, and idling town cars out front. And Le Duc, the first restaurant to serve fish tartare in Paris, has been the go-to for fashion’s A-list and French high society since the 1960s. During Fashion Week, it’s where heavy hitters such as Miuccia Prada and Dior’s Maria Grazia Chiuri go for classics like the sole meunière. Celebrities, artists, royals, and future financial criminals are all desperate to get reservations at these places, in no small part because of the work done by maître d’s.

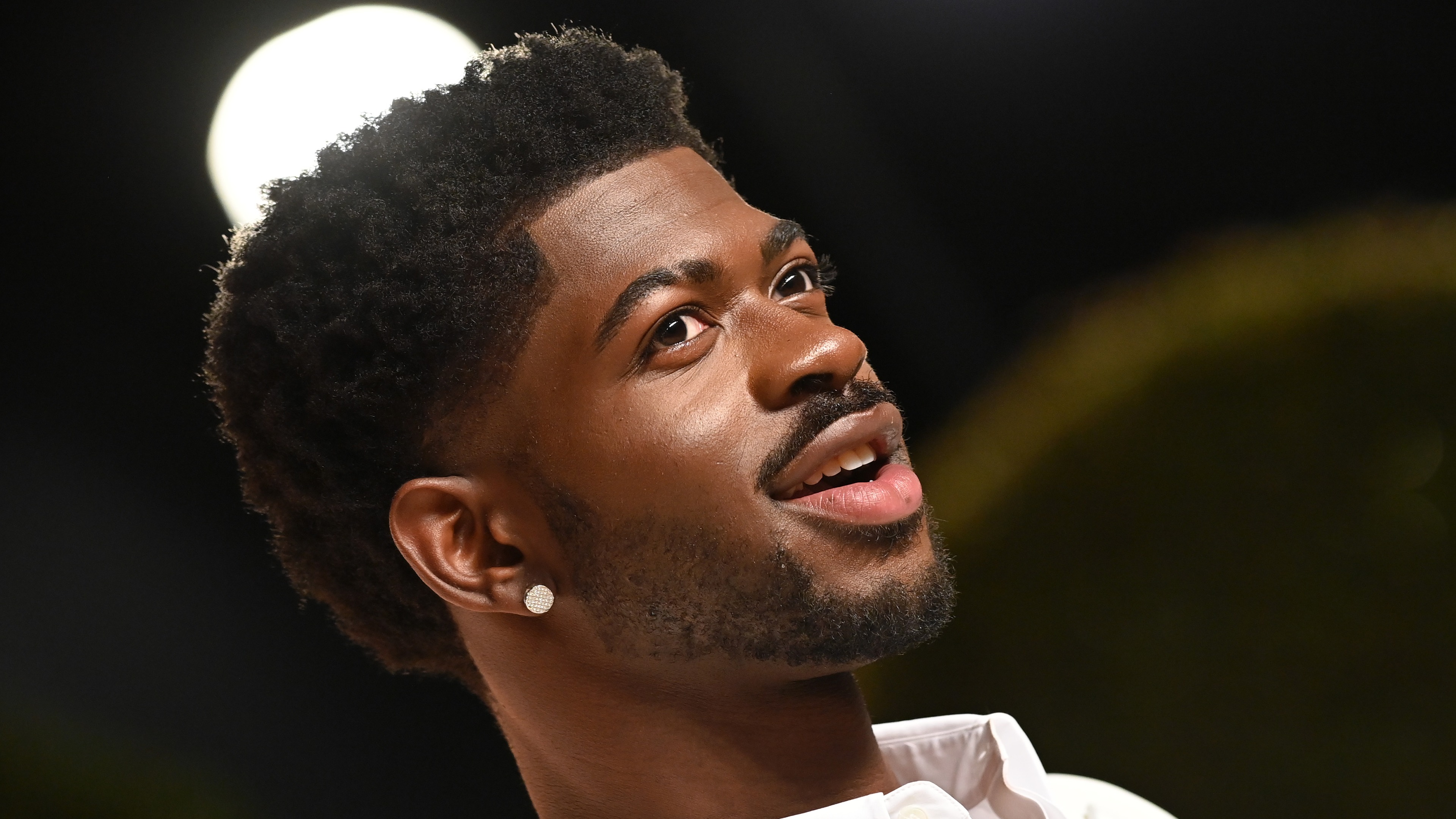

Discretion is of utmost importance—and it’s something in which Gordana Sherriff, the maître d’ at Scott’s for over a decade, is well versed. In the 1990s, Sherriff cut her teeth at the legendary members-only Groucho Club, where the Primrose Hill set let down their hair. Liam Gallagher was thrown out for allegedly smashing a window, and Lily Allen was banned for a month after she got caught doing drugs in the loo. “We were not allowed to speak about what happened in the club and who the members were,” says Sherriff. While some restaurants are full of TikTokers in baggy jeans, at Scott’s there are rules. “We don’t allow people to wander around with their cameras to film other people,” explains Sherriff. At Tower Bar, a favorite of celebrities from Sean Penn to John Mayer, the longtime maître d’, Dimitri Dimitrov, is adept at dealing with big names. “Brad Pitt comes in from the back,” he explains. “Nobody sees him, and I just whisk him toward his table.”

During dinner service, Dimitrov, who is so well known in L.A. that he is the subject of a documentary currently in the works, glides around every banquette, hands steepled by his chest, to say hello in his thick Eastern European accent. “My position is to create the mood of the room,” he explains. He makes sure the lights stay low and keeps the two-piece band at the perfect volume. At Le Duc, “it has to be elegant and, at the same time, casual so people feel at home,” says Dominique Minchelli, who runs the restaurant his father, Jean, opened in 1967. He and the maître d’, Alexandre Yetto, take cues from the guests: “If people want to have fun and talk, we talk more. If some people are more traditional and want fine dining service, we try to do it.” Part of the reason guests feel comfortable at Le Duc—which former French president François Mitterrand frequented weekly—is that the diners are “all in the same league. They don’t bother someone famous next to them. We don’t show photos of them, and we don’t brag.”

The job is not only saying hi, says Contramar’s Armando Camacho, who has worked in the industry for 29 years. “It’s about being kind and humble.” Maître d’s constantly deal with people under the influence, whether they’re drunk on gin or drunk on power. At Polo Bar, the clubby Ralph Lauren–owned favorite of Jennifer Lopez and Tory Burch, Nelly Moudime—the maître d’ since the restaurant’s 2015 opening—knows how to handle fussy clients. “At the end of the day, I cannot carry your issues,” she says. “All I can do is reflect back a little love.” At Tower Bar, Dimitrov has “been called bad names, but I don’t like to make a scene,” he says. Rowdy guests are often quick to repent for their sins, offering him apologies and gifts the next day.

Regulars want what they want. To map out a night’s seating, “first we work with the regulars, who have special demands,” says Minchelli. “Then we fill in between.” If two regulars request the same table, Minchelli doesn’t overthink it. “We just take one at seven and ask the other one to come at nine.” At Scott’s, if a table request is impossible, “it’s better to tell people no before they come in, because you don’t want them feeling bad the minute they’ve arrived in the room,” explains Sherriff.

In Mexico City, “where you eat on Fridays is very important,” says Karla Martinez, the editor in chief of Vogue Mexico and Latin America. At Contramar, “there is always a mix of the standing reservations, from tables of financiers to the group of art gallery women.” Meanwhile, the Polo Bar refuses to give standing tables to VIPs, a rule that comes from Ralph Lauren himself. “People want that, but it’s a different type of restaurant,” says Moudime. If a regular can’t secure a reservation, Moudime never sends a lackey to address the issue. “I’d rather talk to the person,” she says. “You’ll hardly see me send messages that are nondescript.”

Modifications are “an obligation,” says Le Duc’s Yetto. If someone wants to alter a dish, he’ll always check in with the kitchen to see if it’s possible. “I want people to come back.” Famously, Tom Ford, who recommended Dimitrov for his job, asked that the overhead light at his regular Tower Bar table be turned off when he dined. The restaurant installed a special switch to accommodate the request. “It’s not about me,” says Dimitrov. “It’s all about a guest enjoying the moments.”

“You can teach someone how to filet a piece of fish, but you can’t teach people how to be with people,” says Sherriff. “You have to gauge who you need to be deferential to, who you need to be friendlier to. It’s something you simply can’t teach.”

Nelly Moudime: Hair by Mideyah Parker for ORIBE at Bryant Artists; Makeup by Laramie for Bobbi Brown at Day One; Hair Assistant: April Andreu; Makeup Assistant: Kaya Coleman.

Gordana Sherriff: Hair and Makeup by Aga Dobosz for VIEVE at Carol Hayes Management; Production Coordinator: Hattie O’Donell; Photo Assistant: George Eyres.

Minchelli and Yetto: Grooming by Sylvie Mainville for Anastasia Beverly Hills at Carol Hayes Management.

Camacho: Grooming by Fracazototal; Photo Assistant: Renata Montenegro.

-Baldur’s-Gate-3-The-Final-Patch---An-Animated-Short-00-03-43.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)