A breakthrough for photography might have just come from an unexpected place

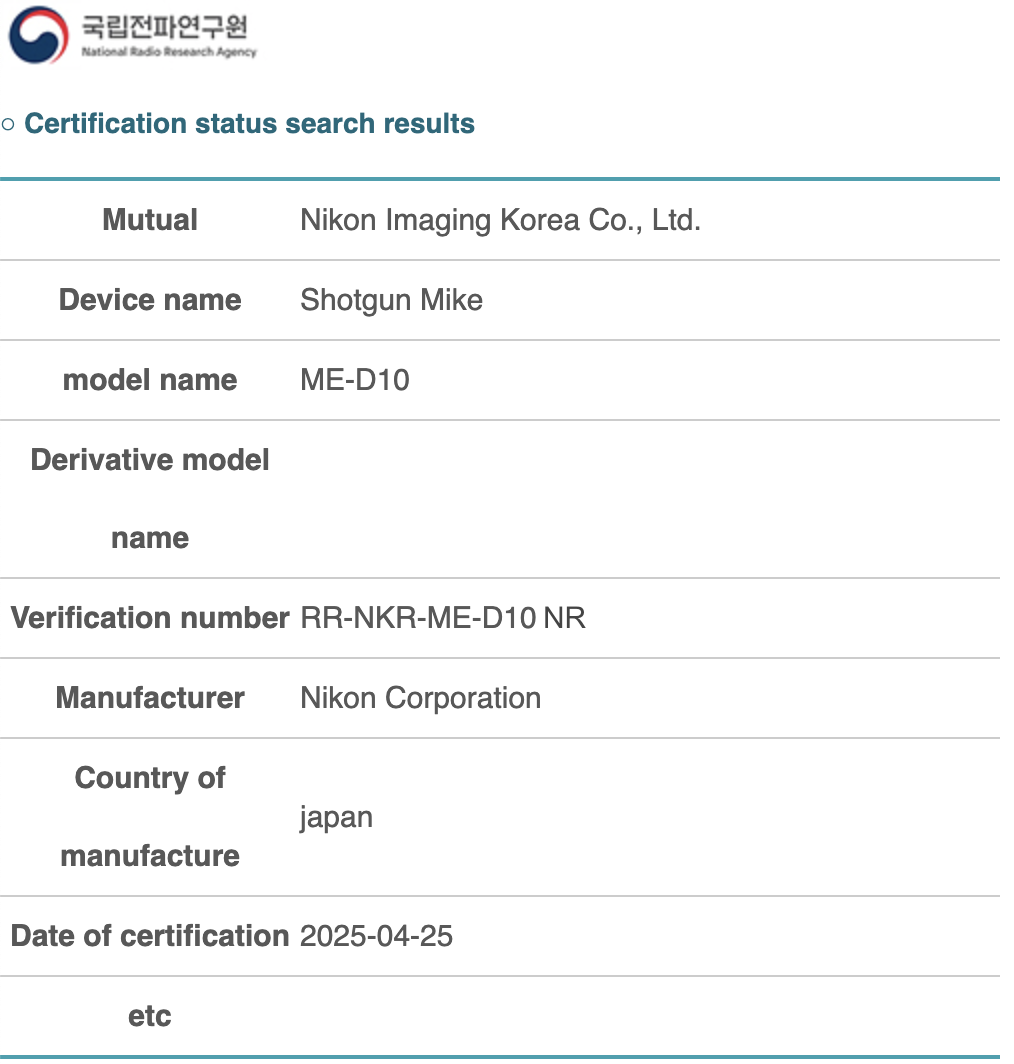

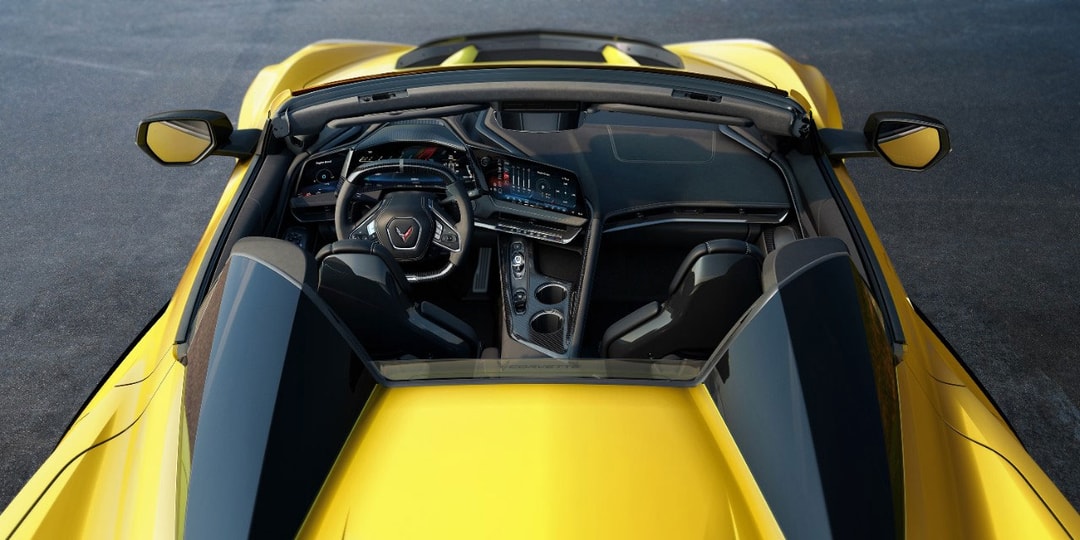

Download this image and open on a recent iPhone or in Preview in MacOS 15 (Sequoia) and the bright edges of the petals should glow. Sigma BF | Sigma 35mm F2 DN | F2.0 | 1/500sec | ISO 200 Photo: Richard Butler Modern displays in the latest phones, TVs and laptops can show a much wider brightness range and a broader array of colors than before, allowing more lifelike images in a way that could revolutionize photography. But a lack of movement toward a format with widespread support has stifled the progress of true HDR photography. Now, just as it looks like the industry might be closing in on a standard, Sigma has quietly delivered an intermediate step that gives more impressive images with full backward compatibility. True HDR The term 'HDR' has been undermined by its association with wide dynamic range captures crudely tone-mapped for standard DR (SDR) displays. The results were often overdone, frequently looking off-putting and gimmicky. True HDR is an attempt to convey more of what your camera captured (even in a single, conventional exposure), by taking full advantage of the greater brightness and color capabilities of modern displays. Instead of looking gimmicky, true HDR can present a more lifelike representation of the world that was possible in print or on SDR displays. It's becoming increasingly common in the video world and on devices such as iPhones to be able to share and view HDR content, but the photo world and camera industry have lagged behind. True HDR imagery really needs more space than the elderly, 8-bit JPEG format can cope with, but nothing else comes close to being as well supported. What's Sigma's middle ground? Embedded in the image at the top of the page is this image, a 1/4 resolution 'gain map' that tells HDR displays where to boost the brightness. The result isn't quite as impressive as full 10-bit images encoded with high dynamic range response curves, but they're an interesting stepping stone on the way and can be viewed as normal on SDR displays. As we were finalising our review of the Sigma BF, we noticed that the JPEGs produced by the Sigma BF look much more punchy and vibrant when viewed on Mitchell's laptop. A little digging revealed that the files include a gain map, which the newer version of Mac OS he was running could interpret. It's an interesting intermediate step: capturing the main image data in the universally-supported JPEG format but embedding an additional version of the image telling HDR displays which parts of the image should be made brighter. The result isn't the best representation of HDR that we've seen, not maintaining the subtle and, crucially, saturated colors on the approach to clipping that can convey the bright 'glow' of evening sunshine or light passing through spring leaves that the best can. But it means that more people might be able to get a taste of what HDR photography can offer, while being certain that other people will be able to see at least an SDR version of their shots. What's the next step? For the full HDR experience, the industry will probably need to adopt a proper HDR response curve - with the Hybrid Log Gamma (HLG) curve developed by broadcasters NHK and BBC looking most likely - along with a file format that can include the 10-bit data required to encode the additional tonal and chromatic range. As things stand, HDR broadcasting has been happening for more than a decade, iPhones are merrily creating HDR photos without their users necessarily knowing, YouTube is happy to support HDR video, but the camera industry is still pulling in different directions. Video and broadcast are a fair way ahead of the photo industry with increasingly widespread support for HDR display. At present, YouTube is the most reliable way of us sharing HDR content. Adobe has finally introduced HDR editing tools to Adobe Camera Raw, but its output formats (AVIF or JPEG XL) are not the ones camera makers appear to be settling on. Sony and Nikon have adopted the HLG curve and HEIF format for their cameras while Canon and Fujifilm can both output HEIF files and shoot video using HLG, but can't combine the two. Panasonic used to output HLG photos in a format that never took off, but there are hints that HEIF support is on the horizon. Being lucky enough to use modern Macbook Pros and having access to Adobe Camera Raw means we're constantly reminded of how much more attractive and compelling HDR could make some of our photos, and frustrated at not having a reliable means of sharing them. While the rest of the industry dithers, Sigma is forging its own path.

Modern displays in the latest phones, TVs and laptops can show a much wider brightness range and a broader array of colors than before, allowing more lifelike images in a way that could revolutionize photography. But a lack of movement toward a format with widespread support has stifled the progress of true HDR photography.

Now, just as it looks like the industry might be closing in on a standard, Sigma has quietly delivered an intermediate step that gives more impressive images with full backward compatibility.

True HDR

The term 'HDR' has been undermined by its association with wide dynamic range captures crudely tone-mapped for standard DR (SDR) displays. The results were often overdone, frequently looking off-putting and gimmicky.

True HDR is an attempt to convey more of what your camera captured (even in a single, conventional exposure), by taking full advantage of the greater brightness and color capabilities of modern displays. Instead of looking gimmicky, true HDR can present a more lifelike representation of the world that was possible in print or on SDR displays.

It's becoming increasingly common in the video world and on devices such as iPhones to be able to share and view HDR content, but the photo world and camera industry have lagged behind. True HDR imagery really needs more space than the elderly, 8-bit JPEG format can cope with, but nothing else comes close to being as well supported.

What's Sigma's middle ground?

As we were finalising our review of the Sigma BF, we noticed that the JPEGs produced by the Sigma BF look much more punchy and vibrant when viewed on Mitchell's laptop. A little digging revealed that the files include a gain map, which the newer version of Mac OS he was running could interpret.

It's an interesting intermediate step: capturing the main image data in the universally-supported JPEG format but embedding an additional version of the image telling HDR displays which parts of the image should be made brighter.

The result isn't the best representation of HDR that we've seen, not maintaining the subtle and, crucially, saturated colors on the approach to clipping that can convey the bright 'glow' of evening sunshine or light passing through spring leaves that the best can. But it means that more people might be able to get a taste of what HDR photography can offer, while being certain that other people will be able to see at least an SDR version of their shots.

What's the next step?

For the full HDR experience, the industry will probably need to adopt a proper HDR response curve - with the Hybrid Log Gamma (HLG) curve developed by broadcasters NHK and BBC looking most likely - along with a file format that can include the 10-bit data required to encode the additional tonal and chromatic range.

As things stand, HDR broadcasting has been happening for more than a decade, iPhones are merrily creating HDR photos without their users necessarily knowing, YouTube is happy to support HDR video, but the camera industry is still pulling in different directions.

Adobe has finally introduced HDR editing tools to Adobe Camera Raw, but its output formats (AVIF or JPEG XL) are not the ones camera makers appear to be settling on.

Sony and Nikon have adopted the HLG curve and HEIF format for their cameras while Canon and Fujifilm can both output HEIF files and shoot video using HLG, but can't combine the two. Panasonic used to output HLG photos in a format that never took off, but there are hints that HEIF support is on the horizon.

Being lucky enough to use modern Macbook Pros and having access to Adobe Camera Raw means we're constantly reminded of how much more attractive and compelling HDR could make some of our photos, and frustrated at not having a reliable means of sharing them. While the rest of the industry dithers, Sigma is forging its own path.