For Nova Scotians, Local Maple Syrup Is a Disappearing Pleasure

Around Valentine’s Day, my parents start watching the weather. They’re waiting for a stretch when the temperatures are above freezing during the day but fall below 32 degrees Fahrenheit at night. This shift in the weather signals the start of maple sugaring season. My family’s home in Northeast Ohio is squarely in the center of North America’s maple sugaring region. Sugar maples grow in a region that stretches from Québec in the North to Tennessee in the South; West to Missouri and Minnesota; and East to the New England Coast, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick. When the sap of these trees is collected and boiled, the water evaporates and leaves a thick, sweet syrup—or, if boiled longer, crystallized maple sugar. The sap, syrup, and sugar of sugar maples have been a traditional food for humans for thousands of years. I’m not talking about Log Cabin or Mrs. Butterworth’s “maple-flavored syrup”; that’s corn syrup and food coloring. Real maple syrup is seasonal, regional, and handmade. The flavor is highly local, affected not only by climate and soil, but processing techniques and bacteria. Tasting the real thing for the first time becomes a core food memory, a turning point in one’s life. But due to a variety of issues, ranging from climate change to waning interest in running small farms, both these plants and processes are dying out in some areas. Which makes maple syrup an ideal candidate for preservation on the Ark of Taste, Slow Food International’s online catalogue of distinctive foods at risk of disappearing. And yet, there is currently only one regional syrup recorded on the Ark: Nova Scotia maple syrup, added by husband and wife Scott Whitelaw and Quita Gray, the proprietors of Sugar Moon Farm in Earltown, NS. I first met Quita as she was working the register at the front of Sugar Moon’s shop and restaurant. Our meeting wasn’t planned: I had just finished breakfast in their dining room, nearly drinking my weight in their exceptional syrup. I’d ordered a meal of biscuits spread with whipped maple butter, waffles made with heirloom Red Fife wheat that I had drowned in syrup, a maple latte, and a bracing, hot maple tonic, made with lemon juice and cayenne pepper. And I planned to take more of the full-bodied, vanilla-forward syrup from their shop home with me. As I browsed the store, Quita had asked me where I was from and what brought me in. I admitted that I was there because I wanted to try the Ark’s only maple syrup. It was purely coincidence that it was Quita and her husband that had been the ones to add Nova Scotia syrup to the Ark of Taste. Quita is humble about the syrup’s inclusion on the Ark. “Any region could submit the same thing. It's a really regional, hyperlocal food. It’s different everywhere,” she told me. “I believe in protecting unique flavors. Is Nova Scotia particularly unique? Probably. But so is Wisconsin syrup. All of them have to be protected because they reflect the terroir of where they are.” But beyond its flavor, she nominated Nova Scotian syrup because of the distinct challenges the local delicacy faces. ”At the time [of the nomination], Nova Scotians were looking into why our yield is so much less and our trees grow so slowly,” she said. “So we had a science committee and they were taking a deep dive into the qualities of our syrup and trying to find out. ’Cause we know it’s exceptional syrup.” The multiple studies that came out of that committee’s research concluded that “syrup from Nova Scotia had higher amounts of minerals, especially magnesium and manganese” as well as higher concentrations of phenolic compounds, such as coniferyl alcohol (a sweet-tasting flavor enhancer), sinapyl aldehyde (offering floral and fruity flavors), and vanillic acid (vanillin: the main flavor component of vanilla), than any other maple syrup samples from Canada or the United States. Not only do these minerals and phenols contribute to the complex flavor of maple syrup, they increase in concentration throughout the season. It’s not known why Nova Scotian syrup has this unique composition, but Quita thinks it’s because they are a maritime sugaring region. Every part of Nova Scotia is less than 50 miles from the ocean, and Quita believes that the weather and the salty sea air have an impact on the soil and trees. Compared to syrup from inland provinces, like Québec, the syrup at Sugar Moon has a unique taste of pine and ocean. And something about the climate makes the trees grow extraordinarily slowly. Whereas in other maple regions, a tree is usually a good size for tapping when it’s 30 or 40 years old, in Nova Scotia, it takes 80 or 100 years. Even when the trees are mature and ready to tap, producers are faced with another challenge: “Our yield is half to a third of what everyone else makes,” Quita added, although it’s unclear why it takes so much more sap to make syrup from Nova Scotian sugar maples. “So we can’t compete as a commodity,” Quita told me. “Then it becomes: ‘How

Around Valentine’s Day, my parents start watching the weather. They’re waiting for a stretch when the temperatures are above freezing during the day but fall below 32 degrees Fahrenheit at night. This shift in the weather signals the start of maple sugaring season.

My family’s home in Northeast Ohio is squarely in the center of North America’s maple sugaring region. Sugar maples grow in a region that stretches from Québec in the North to Tennessee in the South; West to Missouri and Minnesota; and East to the New England Coast, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick. When the sap of these trees is collected and boiled, the water evaporates and leaves a thick, sweet syrup—or, if boiled longer, crystallized maple sugar. The sap, syrup, and sugar of sugar maples have been a traditional food for humans for thousands of years.

I’m not talking about Log Cabin or Mrs. Butterworth’s “maple-flavored syrup”; that’s corn syrup and food coloring. Real maple syrup is seasonal, regional, and handmade. The flavor is highly local, affected not only by climate and soil, but processing techniques and bacteria. Tasting the real thing for the first time becomes a core food memory, a turning point in one’s life. But due to a variety of issues, ranging from climate change to waning interest in running small farms, both these plants and processes are dying out in some areas. Which makes maple syrup an ideal candidate for preservation on the Ark of Taste, Slow Food International’s online catalogue of distinctive foods at risk of disappearing.

And yet, there is currently only one regional syrup recorded on the Ark: Nova Scotia maple syrup, added by husband and wife Scott Whitelaw and Quita Gray, the proprietors of Sugar Moon Farm in Earltown, NS. I first met Quita as she was working the register at the front of Sugar Moon’s shop and restaurant. Our meeting wasn’t planned: I had just finished breakfast in their dining room, nearly drinking my weight in their exceptional syrup. I’d ordered a meal of biscuits spread with whipped maple butter, waffles made with heirloom Red Fife wheat that I had drowned in syrup, a maple latte, and a bracing, hot maple tonic, made with lemon juice and cayenne pepper. And I planned to take more of the full-bodied, vanilla-forward syrup from their shop home with me.

As I browsed the store, Quita had asked me where I was from and what brought me in. I admitted that I was there because I wanted to try the Ark’s only maple syrup. It was purely coincidence that it was Quita and her husband that had been the ones to add Nova Scotia syrup to the Ark of Taste.

Quita is humble about the syrup’s inclusion on the Ark. “Any region could submit the same thing. It's a really regional, hyperlocal food. It’s different everywhere,” she told me. “I believe in protecting unique flavors. Is Nova Scotia particularly unique? Probably. But so is Wisconsin syrup. All of them have to be protected because they reflect the terroir of where they are.”

But beyond its flavor, she nominated Nova Scotian syrup because of the distinct challenges the local delicacy faces. ”At the time [of the nomination], Nova Scotians were looking into why our yield is so much less and our trees grow so slowly,” she said. “So we had a science committee and they were taking a deep dive into the qualities of our syrup and trying to find out. ’Cause we know it’s exceptional syrup.”

The multiple studies that came out of that committee’s research concluded that “syrup from Nova Scotia had higher amounts of minerals, especially magnesium and manganese” as well as higher concentrations of phenolic compounds, such as coniferyl alcohol (a sweet-tasting flavor enhancer), sinapyl aldehyde (offering floral and fruity flavors), and vanillic acid (vanillin: the main flavor component of vanilla), than any other maple syrup samples from Canada or the United States. Not only do these minerals and phenols contribute to the complex flavor of maple syrup, they increase in concentration throughout the season.

It’s not known why Nova Scotian syrup has this unique composition, but Quita thinks it’s because they are a maritime sugaring region. Every part of Nova Scotia is less than 50 miles from the ocean, and Quita believes that the weather and the salty sea air have an impact on the soil and trees. Compared to syrup from inland provinces, like Québec, the syrup at Sugar Moon has a unique taste of pine and ocean.

And something about the climate makes the trees grow extraordinarily slowly. Whereas in other maple regions, a tree is usually a good size for tapping when it’s 30 or 40 years old, in Nova Scotia, it takes 80 or 100 years. Even when the trees are mature and ready to tap, producers are faced with another challenge: “Our yield is half to a third of what everyone else makes,” Quita added, although it’s unclear why it takes so much more sap to make syrup from Nova Scotian sugar maples.

“So we can’t compete as a commodity,” Quita told me. “Then it becomes: ‘How do we differentiate ourselves as something unique that needs to be protected?’”

Quita and her husband have been making syrup in Nova Scotia for 30 years. She grew up on the other side of the continent, in Vancouver, and met Scott while in forestry school. When they graduated, they started looking for land to buy to build a future together.

“And we met the guy that had this place,” Quita said, referring to the rough-wood sugarhouse and the dense, surrounding forest. “He built this place by hand using draft horses, Clydesdales. And when we met him, he was looking for the right people. We had no money. We apprenticed for two years. We learned maple sugaring and horse logging and took over in 1994.”

“We raised three daughters on the farm,” she continued. “The youngest is 19 and she was our sugar baby; she was born right at the peak of the maple season. She’s got a good maple name: Samara. A samara is a seed from a maple tree.”

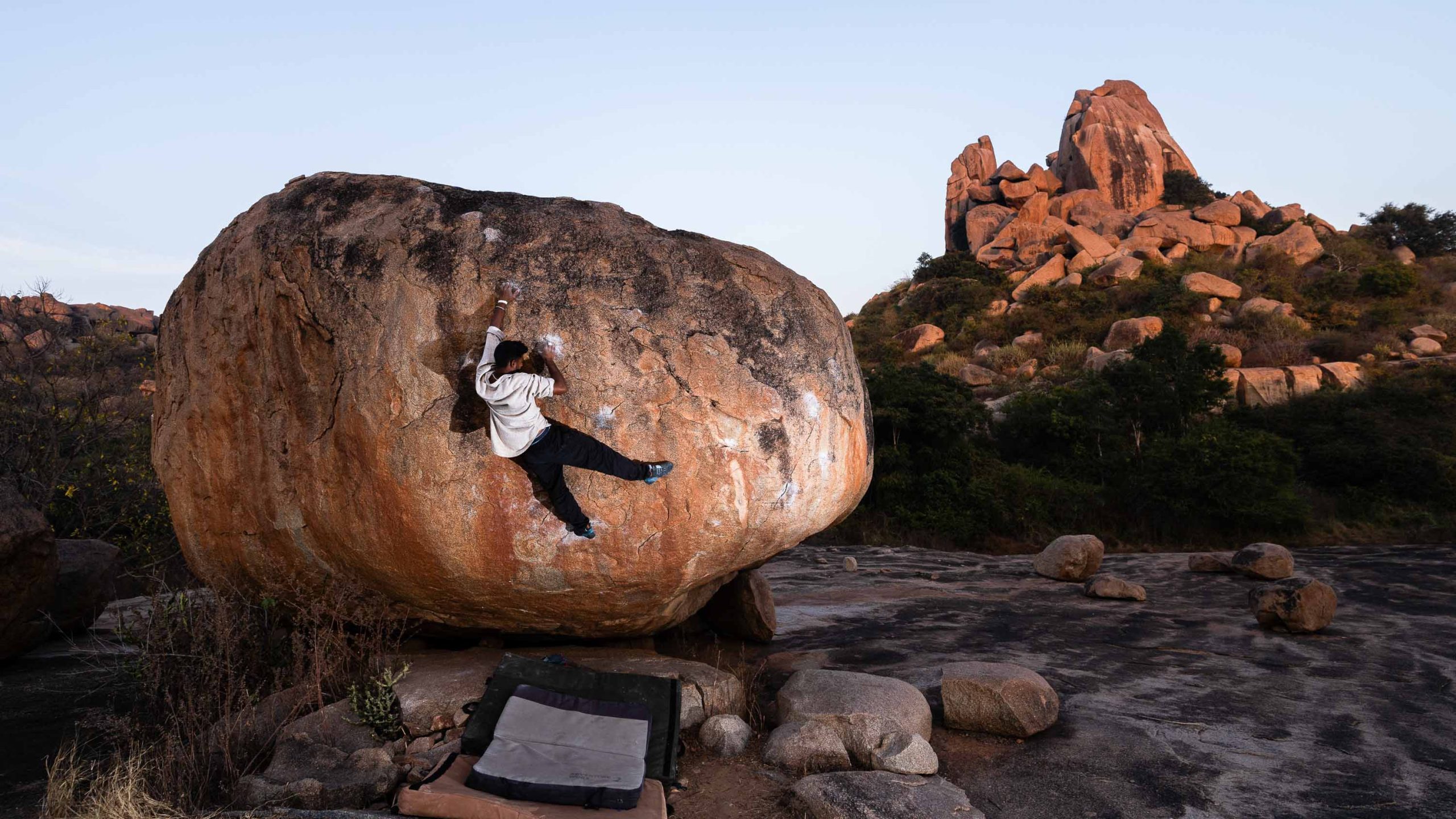

Their sugar bush is 200 acres, with 2,500 taps, spread over a hill. Modern commercial sugar bushes like Sugar Moon’s tend to be on a slope, because rather than spiles dripping into individual buckets, every spile is connected by tubing. “And the sap comes down the hill through the network of tubing by gravity to our camp,” Quita explained.

Quita and her team process the sap in the sugarhouse. Maple sap has a high sugar content, ranging from 1 to 5 percent; but it still takes at least 40 gallons of sap to make one gallon of syrup. The sap first enters a reverse osmosis machine—systems typically used to remove impurities from water, but in this case, it’s the water that maple syrup makers want to remove. Sap gets filtered at high pressure through a semi-permeable filter membrane that’s porous enough for water to flow through, but not the sap’s sugar or other compounds. This system can remove up to 90 percent of the water in sap; so a mid-sized operation that collects 100,000 gallons of sap will only have to boil 10,000 gallons of the concentrated result. That concentrated sap is then boiled off in a wood- or gas-fueled evaporator, until it is 66 to 68 percent sugar syrup.

“At the end of the season we pull taps, clean out the lines, plug them up, push them up the tree,” Quita told me. They are pushed high to avoid the snow, which can be three or four feet high at the start of the season. “Next year when we go back, we will drill a new hole.” And the process starts again.

Quita and Scott organize the syrup at their gift shop by when it was harvested and processed in the season: light, early-season syrup is on one end; dark, pungent late-season syrup on the far side. They don’t blend their syrups for a consistently flavored product; they embrace the differences that come throughout the season, and consumers can hunt for their preferred flavor profile.

Everywhere maple syrup is produced, the first syrup of the season—or “sugarmaker’s syrup” as it's sometimes called—has a light, delicate flavor. It was preferred by early European colonists because of its similarity to processed white cane sugar. But the syrup still has its own unique flavor notes: butter, marshmallow, and vanilla. A mid-season syrup has an amber color; it can taste caramelized, woody, and tannic. End-of-season syrup can be as richly colored as molasses. It often has the most intense “maple” flavor, tasting deeply caramelized, with notes of burnt sugar and rum.

The difference in flavor and color over a single maple season is caused not only by minerals and phenols, but mainly by bacteria—which also happens to be the reason that maple syrup from a small producer tastes better than a large-scale production.

Maple sap naturally contains at least 22 different bacteria, which also live in the tubing and equipment that it’s processed in. These bacteria convert sucrose in maple sap into glucose, which caramelizes more richly, and the presence of three sugars—sucrose, fructose, and glucose—present a more varied flavor than the presence of two. Warming weather throughout the season, along with agitation during the sap-collection process, creates more bacteria, which increases fermentation. Large commercial maple sugar producers clean their lines and equipment more frequently, process more sap faster in a temperature-controlled environment, and seldom expose the maple sap to air or agitation. The result is a more consistent product, which is often blended with syrup from across the season. But small-batch syrup, with all its helpful bacteria, is far more flavorful.

While warm weather during the sugaring season can increase the presence of tasty bacteria, the warming climate can be a detriment to the syrup.

“We had a hurricane two years ago,” Quita told me. “We haven’t made syrup in two years.” She still doesn’t know when they’ll resume operations.

Not only did the hurricane tear out their carefully set gravity lines, but it ripped hundreds of trees out of the ground, destroying their mature crop of slow-growing maples and making the path into their sugar bush virtually impassable. Quita and Scott have always sold syrup from a neighbor who makes an outstanding product but is uninterested in marketing it. They’ve been relying on that neighbor’s supply while they slowly drag downed trees out of the woods.

Nova Scotia is at the far northern edge of the Atlantic Hurricane System, but hurricanes that would historically dissipate before reaching the province are now making landfall. Ocean temperatures are rising as a result of climate change, which increases the frequency and intensity of storms. In the 21st century, a storm is almost three times as likely to strengthen to a Category 3, compared to dates from 1970 to 1999. The increase in destructive weather events have put some sugarmakers out of business. “It finished some operations along the North Shore,” Quita told me. “They will not make syrup again.”

I hiked up the hill to see the decimated sugar bush; hundreds of maple tree trunks were stacked along the rutted path, old taps still visible in some. Climate change is obvious when you look at maple tapping; for centuries, sugarmakers have documented the first day the sap begins flowing. In the past century, the maple sugaring season has shrunk and shifted earlier in the year. According to Timothy D. Perkins, a research professor at University of Vermont Proctor Maple Research Center, Vermont’s maple sugaring season begins at least a full month earlier now compared to the late 1800s. In Nova Scotia, an in-depth study from Dalhousie University found the maple season now starts 10 days earlier than in the 1980s and there has been a 40 percent drop in sap yield in this time, as well.

The biggest fear is that mild winters will affect the temperature and barometric changes that sugar maples need to produce their spring sap surge. If there’s no freeze, there will be no syrup. Multiple studies have noted that warming weather has both shortened the sugaring season and reduced the sugar content in maple sap by about half on average across maples’ entire region. Only advances in technology that have made syrup-making more efficient—such as the reverse osmosis machines—have saved the industry.

But while there is worry that rapid climate change could destroy the industry, preserving maple forests actually helps ward off climate change. Sugar bush forests pull more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than they put out. On average, a temperate sugar maple forest holds 100 tons of carbon. According to the Federation of Québec Maple Syrup Producers, “Québec’s sugar bushes store 744,000 metric tons of carbon per year, eleven times more than maple syrup production creates. This is equivalent to the emissions of 220,000 vehicles or 440 million litres of gas in the same period.”

The entire province of Nova Scotia could be making more maple syrup. The provincial government wants to increase sugaring revenue, but is having difficulty finding younger farmers to take over when older generations retire or get pushed out by the uncertainties of a changing climate. So if you, dear reader, dream of moving to a beautiful region and spending your years tending to a sugar bush, there are resources to support you. The Maple Producers Association of Nova Scotia offers mentorships, funding, and a four-day Maple Sugaring Bootcamp.

And if you live elsewhere in the sugar maple’s magic region, you can start in your own backyard. My parents have been tapping their own trees since 2011. It’s become an important ritual for my family; the first sure sign of spring and one that connects us to traditions much older than written memory.

“Sugar Moon is an Indigenous term,” Quita told me. Their farm is named after Siwkewiku's, the Mi’kmaw term for the March Moon that shines during the sugaring season. The Mi’kmaw’s traditional lands are in Nova Scotia, but most of the Indigenous communities in North America’s entire sugar maple region have relied on maple sugar as a staple food for millennia. “The name acknowledges the roots of our business,” Quita added, between welcoming visitors to the shop. “We started inviting a Mi’kmaw friend to come and bless the season. It reminds us every year: this isn't just a commodity that we're sucking from a tree and selling. This is a gift.”