How Many Other Oceans Exist in Our Solar System?

Think of the last time you had your feet in the ocean. While you were there, did you ever imagine what an ocean on another world might be like? Would it be a different color, a different temperature? Would the waves be taller or the water populated with strange alien creatures? What sort of sky might that sit under? Whatever you were picturing, I’m willing to bet it was on a planet orbiting around a far-flung star. But it turns out that our very own solar system is populated with hidden oceans, trapped not under alien skies, but icy ceilings—and, according to new research, scientists have just uncovered another. One of the moons of Uranus, named Miranda, has only been visited up close (and very briefly) once, way back in 1986 by NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft. Like many nearby moons, it’s a ball of ice, one that scientists suspected was frozen throughout. But at the time, some planetary astronomers noted its intriguing features, including a weird mangle of grooves in its southern hemisphere. What might have made them? What sort of geologic activity is responsible? For a new study, published in October in the Planetary Science Journal, scientists mapped out all these grooves, then ran models to test what sort of turbulent activity could have forged them. Their best answer is that deep below a thick icy crust is a convulsing ocean. They suspect that the ocean is slowly freezing, but that it’s still there, today—giving scientists another place that may have, at some point, been amenable to life, and perhaps contained (or contains) life itself. The solar system is filled with invisible oceans trapped beneath frigid carapaces. That Miranda possibly contains an ocean is inherently remarkable, not least because, unlike Earth’s oceans, Miranda’s is hidden in darkness beneath an icy shell, and it’s never seen sunlight. Imagining the sort of life that may dwell, or might have dwelled, in that ocean—the sort that cannot rely on photosynthesis—is an entertaining thought experiment and recalls some of the weirder animals and microbes that exist on Earth’s own abyssal seafloors, which exist in a state of permanent night. But for planetary scientists, this new study and potential ocean fit in with a surprising recent trend: The solar system is filled with invisible oceans trapped beneath frigid carapaces. And that’s forcing scientists to reconsider what they refer to as a habitable world. Earth is a biological nirvana. But if these moons have (potentially) habitable—if not necessarily inhabited—oceans, then perhaps we shouldn’t consider Earth as the archetypical example of a life-supporting island in the cosmos. In fact, it may be a rarity, with these oceanic moons being the norm. Let’s step back for a moment. In the 1970s, most astronomers and planetary scientists suspected that the plentiful icy moons orbiting the planets of the outer solar system—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—were entirely frozen through. Today, thanks to a fleet of sleuthing spacecraft that have remotely probed the internal structure of some of these moons, scientists know that several of these natural satellites have liquid-water oceans. Saturn’s Enceladus definitely has one sloshing about below its ice shell, which constantly erupts into space via huge chasms on its southern polar region. Jupiter’s Europa almost certainly has one, and NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, which launched in October, is going to confirm this, while checking to see if that ocean is also amenable to life. Several other moons are also thought likely to contain internal oceans, including Saturn’s Mimas and Titan, but the evidence for these is more circumstantial at this stage. The evidence for Miranda’s ocean is also circumstantial, but convincing, not least because it’s easy to explain why it may have an ocean: because it has a weird, wobbly orbit, which at some point powered its inner furnace, turning some of that ice into water. Earth’s internal heat, which drives all its geological processes, comes from two sources: the primordial heat left over from its chaotic, collision-heavy creation, and the heat-producing decay of radioactive matter. An Earth-size planet can insulate the former while containing enough radioactive matter to power it well into the future. But smaller worlds, including tiny moons, don’t have primordial heat remaining from their formation—that’s all leaked out into space by now. And while they probably have some degree of radioactive heat-producing compounds in their rocky innards, it’s nowhere near as much as Earth possesses. Instead, these moons are (mostly) heated by something called tidal heating. Because of the gravitational influence of nearby moons, their orbits around their host planets are elliptical, not circular, which means they get closer to, then further away, from the planets. That alternating gravitational pull means their geologic viscera are being repeatedly kneaded, which creates a lot of friction, and heat—eno

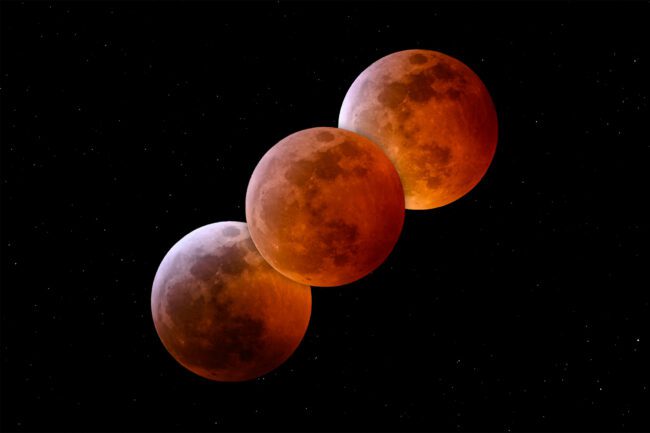

Think of the last time you had your feet in the ocean. While you were there, did you ever imagine what an ocean on another world might be like? Would it be a different color, a different temperature? Would the waves be taller or the water populated with strange alien creatures? What sort of sky might that sit under? Whatever you were picturing, I’m willing to bet it was on a planet orbiting around a far-flung star. But it turns out that our very own solar system is populated with hidden oceans, trapped not under alien skies, but icy ceilings—and, according to new research, scientists have just uncovered another.

One of the moons of Uranus, named Miranda, has only been visited up close (and very briefly) once, way back in 1986 by NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft. Like many nearby moons, it’s a ball of ice, one that scientists suspected was frozen throughout. But at the time, some planetary astronomers noted its intriguing features, including a weird mangle of grooves in its southern hemisphere. What might have made them? What sort of geologic activity is responsible?

For a new study, published in October in the Planetary Science Journal, scientists mapped out all these grooves, then ran models to test what sort of turbulent activity could have forged them. Their best answer is that deep below a thick icy crust is a convulsing ocean. They suspect that the ocean is slowly freezing, but that it’s still there, today—giving scientists another place that may have, at some point, been amenable to life, and perhaps contained (or contains) life itself.

That Miranda possibly contains an ocean is inherently remarkable, not least because, unlike Earth’s oceans, Miranda’s is hidden in darkness beneath an icy shell, and it’s never seen sunlight. Imagining the sort of life that may dwell, or might have dwelled, in that ocean—the sort that cannot rely on photosynthesis—is an entertaining thought experiment and recalls some of the weirder animals and microbes that exist on Earth’s own abyssal seafloors, which exist in a state of permanent night.

But for planetary scientists, this new study and potential ocean fit in with a surprising recent trend: The solar system is filled with invisible oceans trapped beneath frigid carapaces. And that’s forcing scientists to reconsider what they refer to as a habitable world. Earth is a biological nirvana. But if these moons have (potentially) habitable—if not necessarily inhabited—oceans, then perhaps we shouldn’t consider Earth as the archetypical example of a life-supporting island in the cosmos. In fact, it may be a rarity, with these oceanic moons being the norm.

Let’s step back for a moment. In the 1970s, most astronomers and planetary scientists suspected that the plentiful icy moons orbiting the planets of the outer solar system—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—were entirely frozen through. Today, thanks to a fleet of sleuthing spacecraft that have remotely probed the internal structure of some of these moons, scientists know that several of these natural satellites have liquid-water oceans. Saturn’s Enceladus definitely has one sloshing about below its ice shell, which constantly erupts into space via huge chasms on its southern polar region. Jupiter’s Europa almost certainly has one, and NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, which launched in October, is going to confirm this, while checking to see if that ocean is also amenable to life.

Several other moons are also thought likely to contain internal oceans, including Saturn’s Mimas and Titan, but the evidence for these is more circumstantial at this stage. The evidence for Miranda’s ocean is also circumstantial, but convincing, not least because it’s easy to explain why it may have an ocean: because it has a weird, wobbly orbit, which at some point powered its inner furnace, turning some of that ice into water.

Earth’s internal heat, which drives all its geological processes, comes from two sources: the primordial heat left over from its chaotic, collision-heavy creation, and the heat-producing decay of radioactive matter. An Earth-size planet can insulate the former while containing enough radioactive matter to power it well into the future. But smaller worlds, including tiny moons, don’t have primordial heat remaining from their formation—that’s all leaked out into space by now. And while they probably have some degree of radioactive heat-producing compounds in their rocky innards, it’s nowhere near as much as Earth possesses.

Instead, these moons are (mostly) heated by something called tidal heating. Because of the gravitational influence of nearby moons, their orbits around their host planets are elliptical, not circular, which means they get closer to, then further away, from the planets. That alternating gravitational pull means their geologic viscera are being repeatedly kneaded, which creates a lot of friction, and heat—enough to melt their ice and sustain an ocean, at least for as long as they stay in that peculiar orbit.

Miranda may or may not have an ocean. But if it does, which is looking likely, then a certain type of orbit is all that’s needed to explain it. The new study’s simulations show that Miranda used to have a wobbly orbit influenced by its neighboring moons, and although it doesn’t have it today—which is why its ocean is freezing and is a shadow of its former self—it’s plain to see that it once did.

That makes this latest discovery almost routine, because if Jupiter and Saturn can have oceanic moons, why can’t Uranus? And, ultimately, this means that ocean worlds are everywhere—not just in the solar system, but throughout the universe. All you need is ice, a strange orbit, and gravity’s embrace.

No two icy oceanic moons will be alike. Their chemical mélanges will differ, partly because water-ice isn’t the only sort you can get; travel far away from the local star, and stranger matter freezes into ices, including carbon dioxide, ammonia, nitrogen, and methane. Depending on how light interacts with those ices, and potentially breaks some of them down or changes their chemistry, the waterfall of compounds from the moons’ icy shells into the ocean may have consequences for the habitability of those oceans. Some of these oceanic seafloors may have hydrothermal vents, while others may not. Some of these oceans may contain life; maybe none of them do. We don’t know yet.

When it comes to our knowledge of what these watery orbs are actually like, we are just scratching the surface—almost literally with Europa Clipper, which won’t touch the surface of the eponymous moon but will directly sample matter that has been jettisoned off its icy shell by near-constant micrometeorite impacts. But already, planetary scientists are starting to realize that oceanic moons are all over the place in the outer solar system, and although an exomoon—a moon around a planet outside the solar system—has yet to be directly detected, they are certainly out there, waiting to be discovered.

Either way, this new research underscores a key point: our oceanic planet isn’t quite as unique as we once thought. In the sea of stars, Earth is a drop of water. But it is special, because when we wade into its waters, we do so under an atmospheric canopy, not an icy shell. Earth’s oceans sit on the skin of the world and would be exposed to the vacuum of space save for Earth’s substantial atmosphere—a blue mirror to an azure sky.

If there is life in any of these oceans, it will be spectacular, whatever form it comes in. But for now, Earth is the only place we know of that life can stand on the shores of an ocean, or meander through its seas, and see the stars above. Aside from being a rather comforting thought, this also means life on Earth will have evolved in a dramatically different manner compared to life trapped beneath a protective icy shell.

There are almost certainly distant planets that, like Earth, have liquid water oceans flowing underneath an atmospheric bubble. Some of them probably feature life, and perhaps it will more closely resemble Earth’s. But for liquid water to exist and persist on a planetary surface requires that planet to be at the exact right distance from its local star, the so-called Goldilocks Zone. All the icy ocean worlds in our solar system are far removed from that zone, and it seems easier to get a tidally heated icy moon than it does to forge an exposed oceanic world like Earth.

In other words, Earth’s oceanic architecture is increasingly looking like an oddity, rather than a feature, of the universe. That means we should consider ourselves fortunate: we get to splash about in an unusual, sun-soaked, maritime paradise—and as we do so, we can daydream about what sort of life may be out there, swimming in darkness inside their surprisingly ordinary snow globe-like moons.

Robin George Andrews is a doctor of volcanoes, an award-winning freelance science journalist, and the author of two books: Super Volcanoes: What They Reveal About Earth and the Worlds Beyond (2021) and How to Kill an Asteroid: The Absurd True Story of the Scientists Defending the Planet (2024).

![Definitive Ghoul://Re Skill Tree Guide [RELEASE]](https://www.destructoid.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/ghoul-re-skill-tree-guide.webp)

![huNter-: "We're playing much better in practice [than officials] because we don't have pressure"](https://img-cdn.hltv.org/gallerypicture/1fIN0ESmRAShnAGE8-AGsD.jpg?auto=compress&ixlib=java-2.1.0&m=/m.png&mw=107&mx=20&my=473&q=75&w=800&s=bed1184795448ccb785e62e470499ddd#)

.jpeg)