In the Lost Lands is getting trashed critically — but it shows off exactly what genre movies need

In the Lost Lands, the latest collaboration between Hollywood power couple Paul W.S. Anderson and Milla Jovovich, continues the collaboration trend they started back in 2002 with Resident Evil: With him directing and her in the lead role, they make kick-ass, highly stylized genre movies that critics reject. But genre movies deserve care and technical […]

In the Lost Lands, the latest collaboration between Hollywood power couple Paul W.S. Anderson and Milla Jovovich, continues the collaboration trend they started back in 2002 with Resident Evil: With him directing and her in the lead role, they make kick-ass, highly stylized genre movies that critics reject. But genre movies deserve care and technical acumen, too, and Anderson and Jovovich’s projects teem with it. In the Lost Lands is no different.

The only Anderson-directed movie with a score above 50 on Metacritic is 1995’s Mortal Kombat, his sophomore feature. It’s a shame: I would go to bat for almost all of his movies, especially the majority of his visually stunning Resident Evil films, his colorful and frothy Three Musketeers adaptation, his epic Monster Hunter adaptation, and the cult classic Event Horizon. I’m now happy to add In the Lost Lands to that list, even as other critics continue the Anderson bashing. And guess what? Audiences seem to agree with me: With the exception of 2008’s Death Race and Monster Hunter (which was released in December 2020, when COVID-19 quarantines had been lifted, but theater attendance was still unusually low), each of his seven other movies released this century have cleared $100 million at the international box office.

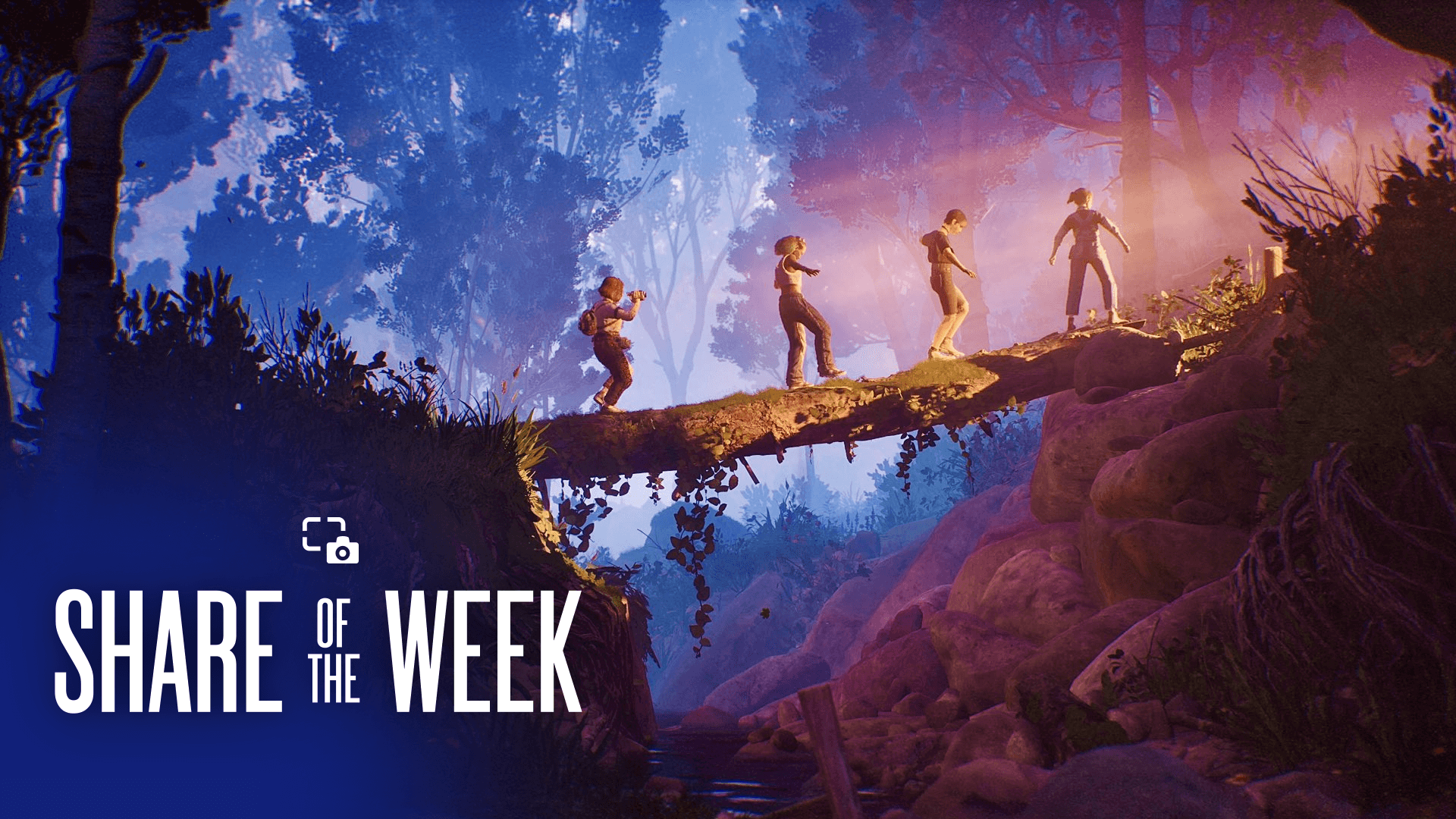

In the Lost Lands is an adaptation of George R.R. Martin’s 1982 short story of the same name. It’s the second feature-length adaptation of Martin’s work, following 1987’s sci-fi horror Nightflyers, based on a novella. The story follows a powerful witch, Gray Alys (Jovovich), who teams up with the fierce hunter Boyce (Dave Bautista) to hunt a werewolf located in the dangerous “Lost Lands,” on request of Queen Melange (Amara Okereke).

Gray Alys’ powerful illusion magic is a rich vein for the movie to explore visually, and Anderson makes the most of it. As she casts spells on people, Anderson immerses the audience in her powers, taking viewers inside the minds of her targets as she swaps places with them, or conjures illusory enemies to attack them. Jovovich is a great fit for the role — as a producer on the movie working with her spouse, she’s obviously on the same page as Anderson creatively. Gray Alys seems afflicted with a curse where she cannot refuse anyone’s request for help (to the movie’s benefit, this isn’t overly explained), and Jovovich imbues the character with an indecipherability and stoicism that works hand in hand with a character whose motivations are mostly unknown to the audience.

Anderson, Jovovich, and screenwriter Constantin Werner build on Martin’s existing post-apocalyptic setting and central conflict, adding details that flesh out the short story and give it a sense of history and mythology. The adaptation retains the original story’s effective mixture of dark fantasy and Western aesthetic elements, while adding a new antagonist in the form of a Christian cult.

Members of this cult dress like Crusaders: They adorn their bodies with cross-influenced makeup and tattoos, but also wear aviators and skulk around with modern pistols, while hanging heretics over crosses. It’s a strong, effective aesthetic choice that adds texture and political drama to the broken-world setting of In the Lost Lands, as a powerful group takes advantage of widespread misery by selling their own success and comfort as belonging to the people.

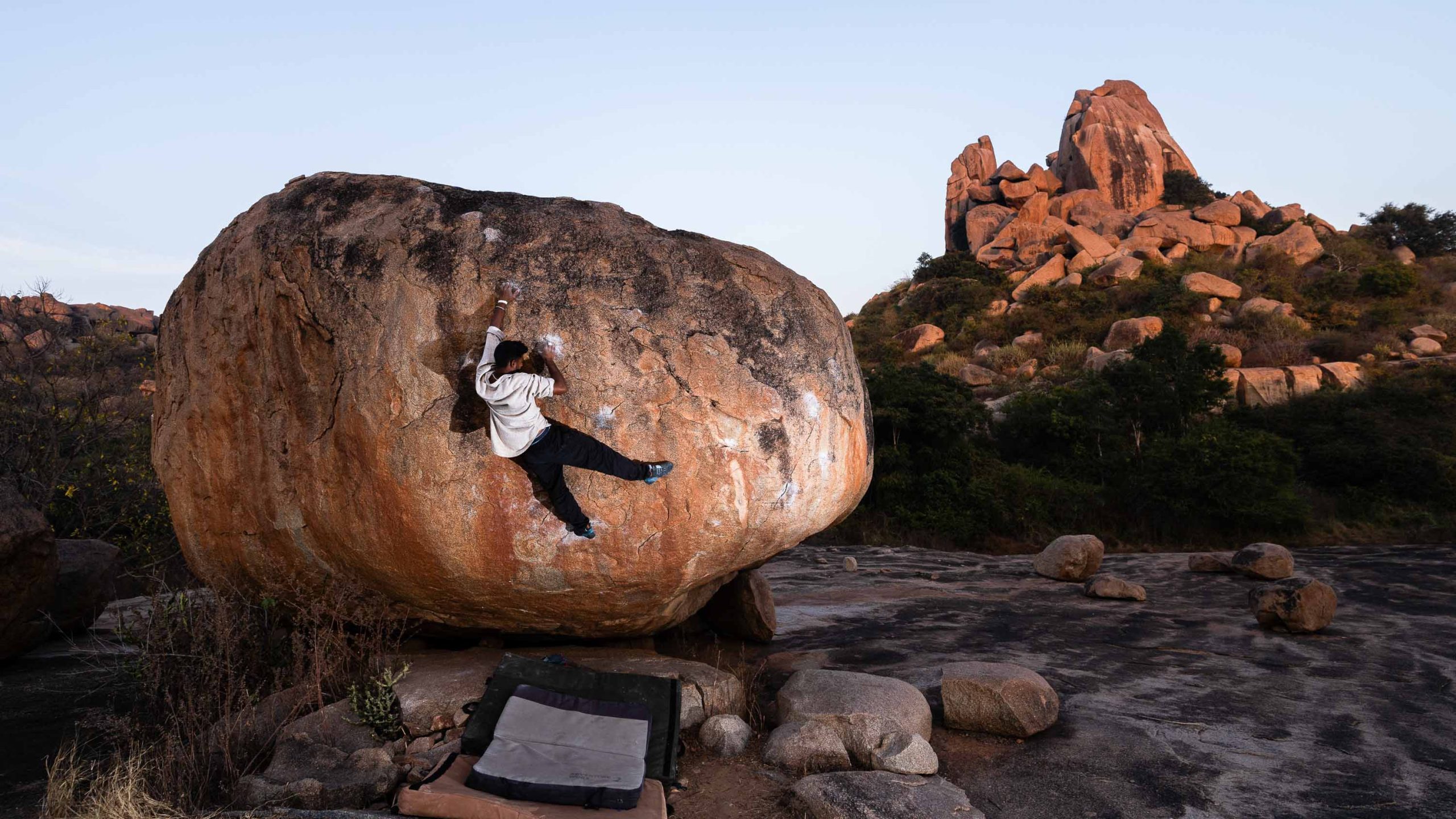

Those little details add up, and Anderson is able to make an aesthetic I don’t usually go for (muted gray and brown tones) work very well because of his skill at lighting and the pops of color he adds to draw your focus. When we first meet Boyce, he’s walking into an ambush under an abandoned freeway overpass. As he realizes what he’s walking into, the camera zooms in on a very tight shot on his face, and Anderson lights it so that you can only see a sliver of Bautista’s eyes under the brim of his hat.

It’s a very Sergio Leone shot — an inspiration Anderson told Polygon via video interview was very much on his mind during production — and it perfectly sets up the destruction Boyce brings upon his would-be ambushers moments after. In other moments, Anderson contrasts his muted colors with bright red blood or sharp firelight, giving brief glimmers of clarity and hope in a chaotic environment.

Anderson’s world-building and eye for compelling visuals throws you right into the sheer scale of In the Lost Lands, evoking massive castles and other huge structures in this desolate land with the unnatural sheen of digital photography and his strong eye for light and shadow. Martin’s typically evocative location names also help out: The protagonists visit Fire Fields, Shadow’s Bane, and my personal favorite, Skull River (which is, it turns out, a more literal name than you might expect).

In the Lost Lands’ clever visual transitions also add life and color to the movie: One repeated interstitial tracks the days until the full moon (for werewolf reasons), with slivers of the moon slotting into a satisfyingly mechanical lunar phase tracker as the story progresses. In classic Martin fashion, Anderson also relies on a fantasy-style map, showing the protagonists’ journey at various points, then zooming in on an area of the map as a scene transition, with the image of the new locale drawn on the map, then shown in live action.

And that live action eventually leads to some live action. The fight sequences in In the Lost Lands also excel, because of their creativity, sense of space, and use of the dark fantasy setting. It helps to have action stars with Jovovich’s and Bautista’s physical skills in play, and Anderson’s vision shines through them. Bautista’s Boyce character has a trick long-barrelled gun that he leaves on his horse as bait for people trying to steal from him, though when they try, they discover a very loyal two-headed snake wrapped around the barrel, ready to protect its master. Our first introduction to the movie’s werewolf is a scintillating point-of-view sequence that shows the lycanthrope decimating a handful of enemies at terrifyingly high speeds. And there’s a positively electrifying cable car sequence late in the movie, where our heroes have to fight dozens of bad guys while traversing across a giant chasm.

These big action scenes are melodramatic as well as exciting, filled with high-stakes combat and outlandish set-pieces. They could be read as over the top, but that’s an essential trait of epic dark fantasy. And the high level of skill necessary to pull these sequences off shouldn’t be dismissed as shallow fun.

I’ve spent quite a bit of time thinking about why critics reject Anderson’s movies and other genre cinema like them. I think a few factors contribute: a general cultural attitude that art that isn’t a certain type of serious drama can’t truly be good, a lack of respect for the technical work that goes into these projects because the aesthetic comes off as frivolous or fun, and an overemphasis on the admittedly weaker dialogue in these projects. (A lot of critics, naturally, are drawn first to words.) But genre cinema isn’t frivolous, and it deserves the same level of care and skill that goes into more “serious” projects. Through In the Lost Lands and the rest of his work, Anderson has shown an incredible eye for detail, and an ambition to push the cinematic language of action forward with new ideas and the new technology afforded by cinema’s digital age. Maybe one day, critics will notice it, too.

In the Lost Lands is in theaters now.