These Fantastic Spanish Sculptures Were Built to Burn

From the outside, Estudio Chuky looks like any of the unassuming warehouses that dot Carrer Camp Rodat, a street in Valencia’s Benaguasil industrial district. But step inside its tall steel doors, and you won’t find containers or trucks. Instead, there’s a 10-foot tall octopus hanging from the ceiling. Beneath it, a team of five artists is busy sanding, sculpting, and painting paper-mâché statues commissioned for Las Fallas, Valencia’s largest festival. During Las Fallas, a ritual inscribed by UNESCO as part of humanity’s intangible cultural heritage, more than 700 effigies, called fallas, are installed around the city and burned in a giant bonfire on the evening of March 19. Making a falla takes months of work and coordination between commissioners and falla artists, local craftsmen who typically learn how to make these ephemeral sculptures from their elders. Raúl “Chuky” Martínez, the creative director of Estudio Chuky, learned to make fallas from his father and grandfather. To make sure this craft gets passed down to the next generation, he is now running a digital portal to promote falla artistry and artists beyond Valencia. During the first two weeks of March, the streets of Valencia are filled with fiery performances, from daily firecracker exhibitions to evening firework shows. Everything culminates with the cremà, the burning of the fallas on March 19. Some sources trace its origin back to pagan spring rituals, while others believe it to be a spin-off of a local tradition whereby carpenters used to burn old furniture to celebrate their patron saint, Saint Joseph. According to Tono Herrero, head of exhibition design at the Valencia Museum of Ethnology and member of the Fallas Studies Association, the first written evidence of fallas burned in the streets dates back to 1777. During the second half of the 19th century, Herrero says, Las Fallas turned from a subversive street festival to an official celebration embraced by religious and political authorities. Today, Las Fallas is Valencia's biggest celebration, overshadowing both Christmas and Easter. “Las Fallas is deeply ingrained in local society,” says Christian García Almenar, a native Valencian currently living in the United States. Each neighborhood in Valencia has a group called an association fallera, tasked with commissioning its own original effigy. Neighborhoods compete with each other to build the most impressive falla. Of the more than 700 sculptures built each year, the one that gets the most votes is spared by the final bonfire and preserved inside Valencia’s Fallas Museum. Friendly competition and a desire to showcase local creativity make Las Fallas a very heart-felt festival, García Almenar says. “Pretty much year-round you can find people in cafes discussing which falla they are going to build.” Once members of a fallas association decide on a theme, they commission an artist to realize their vision. It takes eleven months to go from initial sketch to finalized falla, says Martínez, who works alongside five team members at Estudio Chuky. “First, we model the foam into a skeleton sculpture,” Martínez explains. “On top of this we create a sort of paper-mâché layer that is covered with plumber’s putty, sanded, and then colored.” Each element of a falla makes up a scene that tells a story. Part of falla-making is helping viewers decode these scenes by providing leaflets, called librets, that use poetry to add context. Up until a generation ago, fallas were made of wood, paper and wax, but in recent decades craftsmen have included modern tools like polystyrene foam and 3-D printers. Fallas can range from grotesque caricatures of politicians—the past few festivals featured giant effigies of Trump and Putin—to moving depictions of natural beauty or playful cartoon characters. As explained by Gil-Manuel Hernández Martí, a professor of history and sociology at the University of Valencia, these ephemeral sculptures serve as tools for social critique. “People create fallas to criticize power,” he says, “and they are burned in an act of collective exorcism.” Martínez believes that the best fallas are born out of collaboration with people who have lived experience of a chosen theme. Two years ago, he worked with a woman who had a mastectomy in order to create a falla on the subject of breast cancer. This year, he worked with Marina Salazar, a designer from Barcelona’s College of Arts and Design, to make an effigy of a girl going to space for a falla on the theme of women’s empowerment. Once the effigies are completed, members of the fallas associations help transport the artworks to their neighborhoods, where they need to be fully installed before March 16. It can take up to ten days to install the most elaborate sculptures, with craftsmen working day and night to assemble each piece using cranes and mechanical arms. Between March 16 and March 19, anyone in Valencia can view and vote for their favorite effigy. The climax of the fes

From the outside, Estudio Chuky looks like any of the unassuming warehouses that dot Carrer Camp Rodat, a street in Valencia’s Benaguasil industrial district. But step inside its tall steel doors, and you won’t find containers or trucks. Instead, there’s a 10-foot tall octopus hanging from the ceiling. Beneath it, a team of five artists is busy sanding, sculpting, and painting paper-mâché statues commissioned for Las Fallas, Valencia’s largest festival.

During Las Fallas, a ritual inscribed by UNESCO as part of humanity’s intangible cultural heritage, more than 700 effigies, called fallas, are installed around the city and burned in a giant bonfire on the evening of March 19. Making a falla takes months of work and coordination between commissioners and falla artists, local craftsmen who typically learn how to make these ephemeral sculptures from their elders. Raúl “Chuky” Martínez, the creative director of Estudio Chuky, learned to make fallas from his father and grandfather. To make sure this craft gets passed down to the next generation, he is now running a digital portal to promote falla artistry and artists beyond Valencia.

During the first two weeks of March, the streets of Valencia are filled with fiery performances, from daily firecracker exhibitions to evening firework shows. Everything culminates with the cremà, the burning of the fallas on March 19. Some sources trace its origin back to pagan spring rituals, while others believe it to be a spin-off of a local tradition whereby carpenters used to burn old furniture to celebrate their patron saint, Saint Joseph.

According to Tono Herrero, head of exhibition design at the Valencia Museum of Ethnology and member of the Fallas Studies Association, the first written evidence of fallas burned in the streets dates back to 1777. During the second half of the 19th century, Herrero says, Las Fallas turned from a subversive street festival to an official celebration embraced by religious and political authorities. Today, Las Fallas is Valencia's biggest celebration, overshadowing both Christmas and Easter.

“Las Fallas is deeply ingrained in local society,” says Christian García Almenar, a native Valencian currently living in the United States. Each neighborhood in Valencia has a group called an association fallera, tasked with commissioning its own original effigy. Neighborhoods compete with each other to build the most impressive falla. Of the more than 700 sculptures built each year, the one that gets the most votes is spared by the final bonfire and preserved inside Valencia’s Fallas Museum. Friendly competition and a desire to showcase local creativity make Las Fallas a very heart-felt festival, García Almenar says. “Pretty much year-round you can find people in cafes discussing which falla they are going to build.”

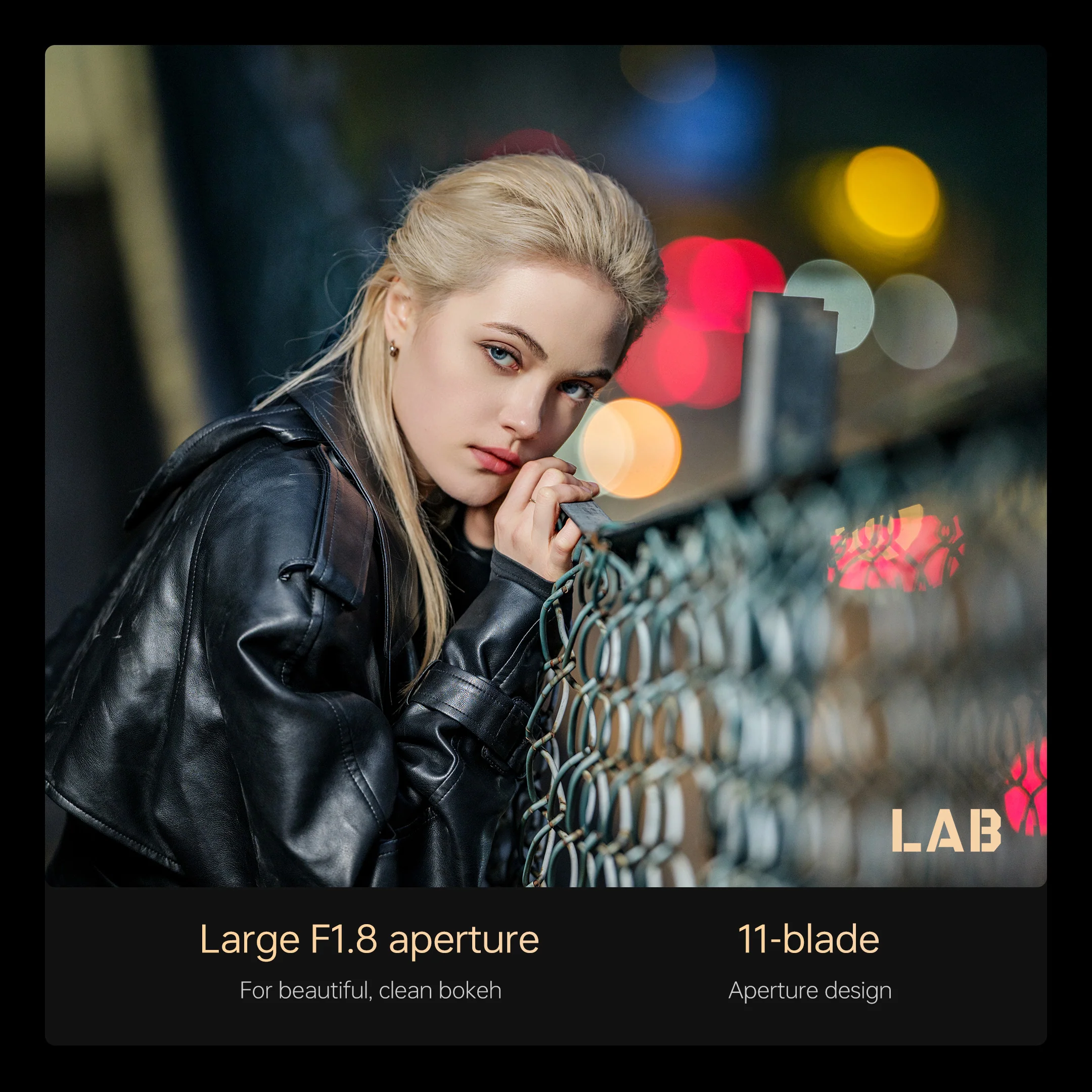

Once members of a fallas association decide on a theme, they commission an artist to realize their vision. It takes eleven months to go from initial sketch to finalized falla, says Martínez, who works alongside five team members at Estudio Chuky. “First, we model the foam into a skeleton sculpture,” Martínez explains. “On top of this we create a sort of paper-mâché layer that is covered with plumber’s putty, sanded, and then colored.” Each element of a falla makes up a scene that tells a story. Part of falla-making is helping viewers decode these scenes by providing leaflets, called librets, that use poetry to add context.

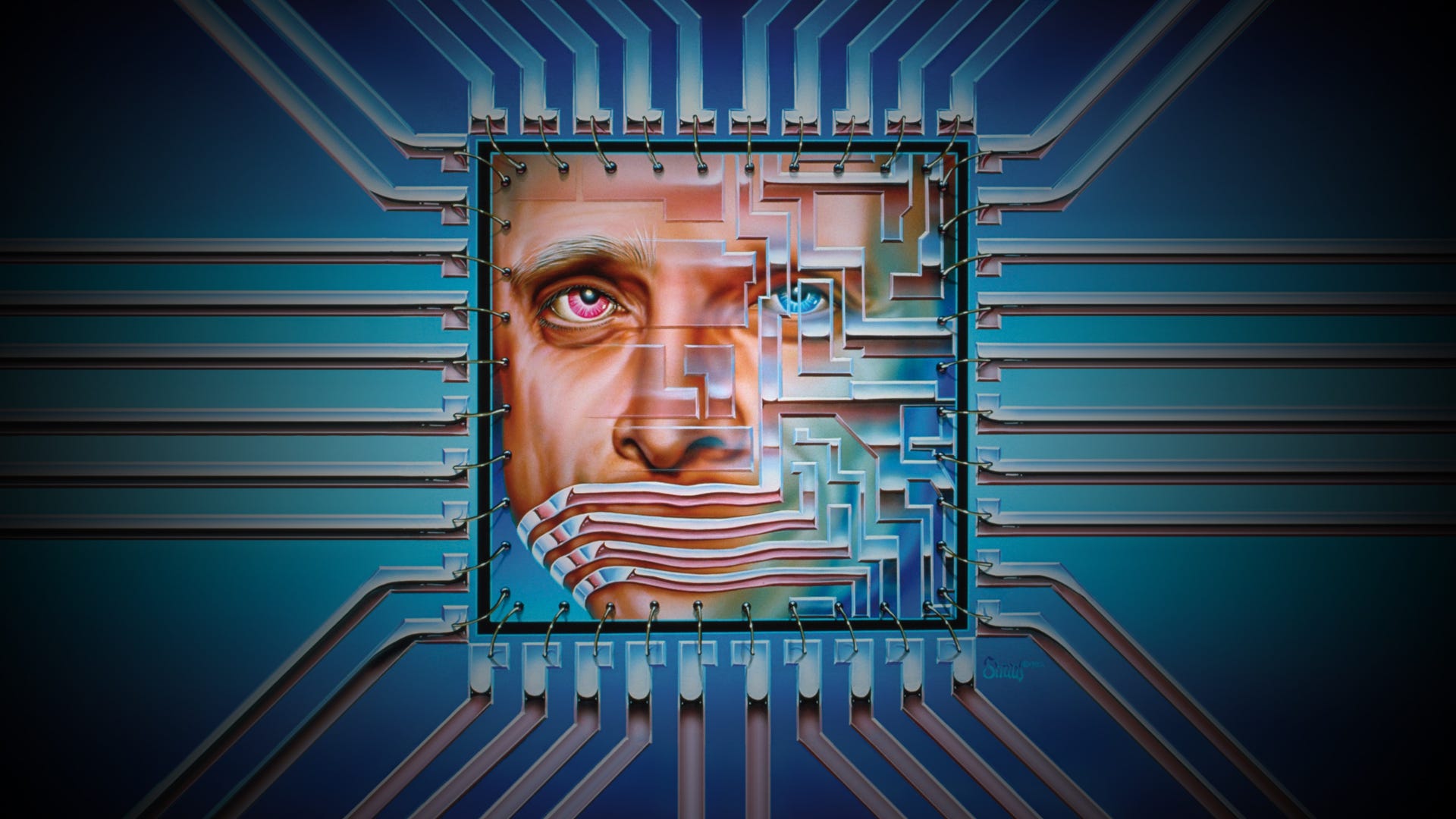

Up until a generation ago, fallas were made of wood, paper and wax, but in recent decades craftsmen have included modern tools like polystyrene foam and 3-D printers. Fallas can range from grotesque caricatures of politicians—the past few festivals featured giant effigies of Trump and Putin—to moving depictions of natural beauty or playful cartoon characters. As explained by Gil-Manuel Hernández Martí, a professor of history and sociology at the University of Valencia, these ephemeral sculptures serve as tools for social critique. “People create fallas to criticize power,” he says, “and they are burned in an act of collective exorcism.”

Martínez believes that the best fallas are born out of collaboration with people who have lived experience of a chosen theme. Two years ago, he worked with a woman who had a mastectomy in order to create a falla on the subject of breast cancer. This year, he worked with Marina Salazar, a designer from Barcelona’s College of Arts and Design, to make an effigy of a girl going to space for a falla on the theme of women’s empowerment.

Once the effigies are completed, members of the fallas associations help transport the artworks to their neighborhoods, where they need to be fully installed before March 16. It can take up to ten days to install the most elaborate sculptures, with craftsmen working day and night to assemble each piece using cranes and mechanical arms. Between March 16 and March 19, anyone in Valencia can view and vote for their favorite effigy.

The climax of the festival takes place on the evening of March 19, when trained firefighters carefully light up each work of art, save for the one spared by voting. The last falla burned is the one located in Valencia’s main square, the Plaza del Ayuntamiento, which usually represents a theme connected to current affairs like war or climate change. “Even after many years, that last big bonfire really gets at me,” Martínez says. “It is magical to watch the work you put together in twelve months disappear in front of your eyes.”

In 2006, UNESCO declared falla artists to be part of humanity’s intangible heritage due to their unique craftsmanship and the vital role they play for local social identity. Last October, when Valencia was hit by catastrophic floods that killed more than 200 people, many fallas associations became improvised disaster relief areas, with falleros helping to clean up the mud and coordinating the delivery of food and medicine. This kind of solidarity is a key trait of Las Fallas, a celebration that works as social glue, says Professor Hernández Martí. “Fallas associations act as connecting tissue between individual households and wider society,” he explains. “And falla artists are a key part of this connection.”

But in recent years, the rising cost of materials and pandemic lockdowns have put pressure on the works of these iconic craftsmen. In 2020, for the first time in decades, Las Fallas was canceled, due to the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic. “My family relied on my income as a falla artist,” Martínez explains. “I had to quickly find another way to get work.”

Together with three other artists, Xavi Serra, Damiá Castaño, and Lluís Alandete, Martínez launched a portal called Regala Un Ninot to connect falla artists with clients interested in ordering ad-hoc effigies. “At the beginning we were getting commissions from friends and family out of solidarity,” he says. “But after a few months, we started to get more orders and realized that there was a market for our artworks.”

By the end of 2020, the website facilitated the creation and delivery of more than 1,000 effigies across Spain and Europe. In 2021, the four founders were selected for a business accelerator program run by Valencia’s municipality and expanded their website into a portal offering different services that monetize the skills of falla artists, from Valua, which lets anyone order large effigies, to Artistas Falleros, a website allowing companies and schools to book team-building activities at fallas workshops.

With their startup, Martínez and his co-founders have channeled some of the Las Fallas spirit of collaboration into the digital realm. “It’s amazing to see how much traffic we got once we launched,” he says. Last year, collective revenues from the portals reached one million Euros. “For a large company that is peanuts,” Martínez says, “but for a startup born out of a crisis, it is more than we would ever have imagined.”

He now hopes that by connecting with clients from around the world, local artists can keep making fallas and pass their craftsmanship down to the next generation. “We know that we have a unique craft here in Valencia,” he says. “And now we can make it available to anyone around the world.”