Wolves Have a Bad Reputation. One Yellowstone Naturalist Is Trying to Fix It.

The wolves trot out of the morning fog and settle around a bison herd that had overnighted in the Lamar Valley of Yellowstone National Park. There are a couple hundred bison and only four wolves, but the herd immediately becomes agitated—they begin to move around, and the wolves follow. A human family of four, we watch them from a hill across the valley, sometimes through the scopes that our guide, Audra Conklin Taylor, has brought along, sometimes just squinting in the morning sun. “The adult bison are too big for them so they’re after the calves,” she explains. “Poor things,” we gasp, imagining one of the fluffy, light-brown creatures becoming breakfast. But as Taylor explains the complexity of the Yellowstone ecosystem, our perspective shifts. As apex predators, wolves are vital for Yellowstone ecology and health: They keep the herds in check, preventing overgrazing. After wolves had been killed off here in the 1920s, the elk, bison, and deer populations exploded, destroying trees, valleys, and riverbanks. “When wolves were reintroduced in 1995, scientists watched the entire park rebound,” Taylor says. It was a result of the “trophic cascade of ecological change”—a ripple effect of removing or introducing a top predator into a food web—which first brought back the trees, followed by beavers and birds, who rely on trees for their living environment. Culturally and historically, wolves have earned a bad rep because they preyed on farmers’ cows. Written records ascribe all kinds of evil qualities to them. The Bible refers to wolves as metaphors for greed and destructiveness. Fairy tales like “Little Red Riding Hood” portray them as preying on humans. Some stories even assign paranormal qualities to them, such as werewolves. And modern media still perpetuates wolves’ negative image in cartoons and movies. “They have been demonized to us since we were children,” Taylor points out. In reality, however, wolf attacks on humans are extremely rare, which differs drastically from, say, grizzlies. “If you were to walk up on a grizzly bear eating a carcass, that grizzly bear is going to come after you full force,” Taylor says. “If you walk up on a carcass and there are wolves, they are likely going to run away. They are afraid of us. They want nothing to do with us.” Part of Taylor’s job is restoring wolves’ reputation. She has spent her life caring for orphaned and injured wildlife, and describes herself as a naturalist. Originally from Massachusetts, Taylor fell in love with Yellowstone after she vacationed there in 2010 with her mother. Four years later, she sold her company and decided to come back to spend three months in nature. “And three months turned into 12 years,” she says. At first, she was volunteering, shadowing wildlife biologists and working with park guides. Then, she started to take groups to see the park’s spectacular wildlife and launched her own company, Lamar Valley Touring, based in Gardiner, Montana. We’re on one of her tours that morning at Yellowstone. As we watch, the hunting scene in front of us escalates. The wolves single out a parentless calf and give chase. The calf gallops, the wolves circle, the calf turns back, skids, careens, loses speed—but just as one wolf leaps for the kill, a huge bull cuts in between. The wolves miss. “Poor things, now they’ll go hungry,” we say as the foursome leaves the battlefield. After everything we’ve learned about their role in the ecosystem, we now see the importance of a successful hunt. “They are used to being hungry,” Taylor says, adding that wolves are resilient and adaptable. “Most hunts aren’t successful. These four look young. They’re juveniles, so it’s not surprising they missed.” Wolves occupy a special place in Taylor’s heart. “They’re so incredibly misunderstood and so incredibly parallel to us humans,” she says. A wolf pack is a family unit, sometimes with “friends” who join in for genetic diversity, “because wolves are too smart to interbreed,” she says. Packs usually have an alpha male and an alpha female, who sire pups, some of which may stay with the pack while others may leave. Sometimes, a pack is run by an old matriarch, a grandma who keeps pups in check. Sometimes more than one female in a pack gives birth, so they rear the pups together, taking turns babysitting. Young female or male wolves may babysit, too, just like older human cousins do. Although protected inside Yellowstone, wolves can be hunted once they leave the park. In 2022, NPR reported that a record number of wolves were shot outside the park—25, which amounted to 20 percent of the wolf population. In 2025 so far, about 10 wolves that ventured beyond Yellowstone’s borders have been killed. Although the park rangers and biologists aren’t yet sure of the exact numbers, they no longer see the pack members they used to see, says Rick McIntyre. McIntyre is a world-famous wolf expert and author of a book series about Yellowstone wolves, including Thinking Like a

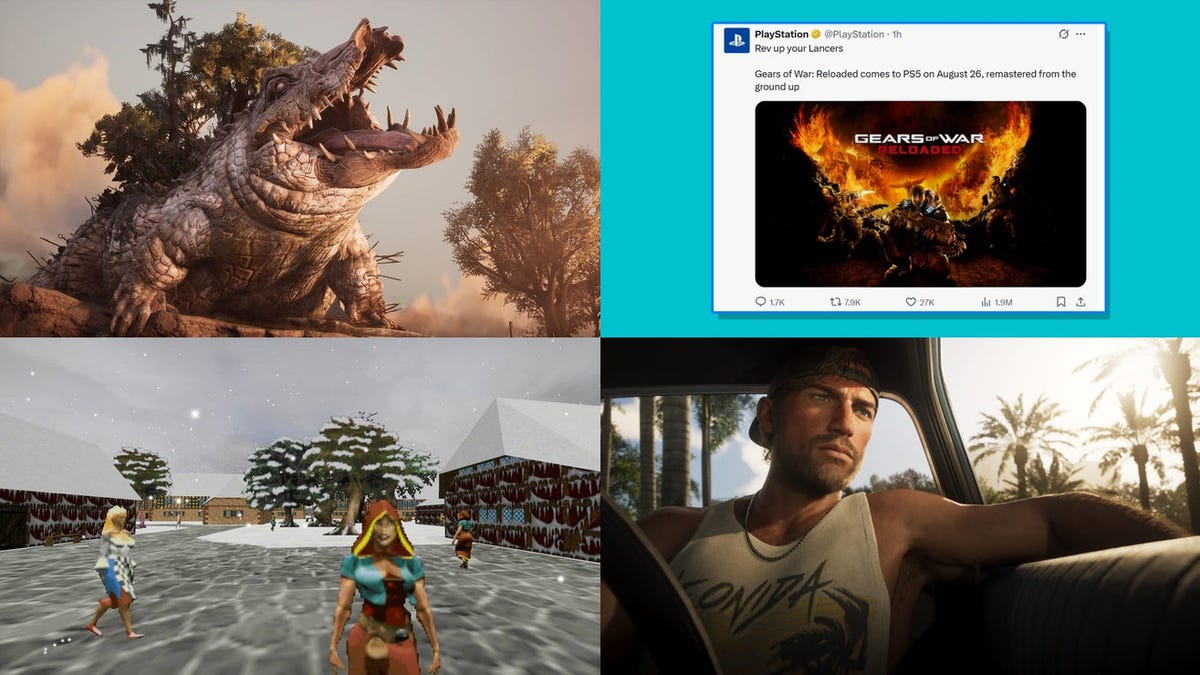

The wolves trot out of the morning fog and settle around a bison herd that had overnighted in the Lamar Valley of Yellowstone National Park. There are a couple hundred bison and only four wolves, but the herd immediately becomes agitated—they begin to move around, and the wolves follow. A human family of four, we watch them from a hill across the valley, sometimes through the scopes that our guide, Audra Conklin Taylor, has brought along, sometimes just squinting in the morning sun. “The adult bison are too big for them so they’re after the calves,” she explains.

“Poor things,” we gasp, imagining one of the fluffy, light-brown creatures becoming breakfast. But as Taylor explains the complexity of the Yellowstone ecosystem, our perspective shifts. As apex predators, wolves are vital for Yellowstone ecology and health: They keep the herds in check, preventing overgrazing. After wolves had been killed off here in the 1920s, the elk, bison, and deer populations exploded, destroying trees, valleys, and riverbanks.

“When wolves were reintroduced in 1995, scientists watched the entire park rebound,” Taylor says. It was a result of the “trophic cascade of ecological change”—a ripple effect of removing or introducing a top predator into a food web—which first brought back the trees, followed by beavers and birds, who rely on trees for their living environment.

Culturally and historically, wolves have earned a bad rep because they preyed on farmers’ cows. Written records ascribe all kinds of evil qualities to them. The Bible refers to wolves as metaphors for greed and destructiveness. Fairy tales like “Little Red Riding Hood” portray them as preying on humans. Some stories even assign paranormal qualities to them, such as werewolves. And modern media still perpetuates wolves’ negative image in cartoons and movies.

“They have been demonized to us since we were children,” Taylor points out. In reality, however, wolf attacks on humans are extremely rare, which differs drastically from, say, grizzlies. “If you were to walk up on a grizzly bear eating a carcass, that grizzly bear is going to come after you full force,” Taylor says. “If you walk up on a carcass and there are wolves, they are likely going to run away. They are afraid of us. They want nothing to do with us.”

Part of Taylor’s job is restoring wolves’ reputation. She has spent her life caring for orphaned and injured wildlife, and describes herself as a naturalist. Originally from Massachusetts, Taylor fell in love with Yellowstone after she vacationed there in 2010 with her mother. Four years later, she sold her company and decided to come back to spend three months in nature.

“And three months turned into 12 years,” she says. At first, she was volunteering, shadowing wildlife biologists and working with park guides. Then, she started to take groups to see the park’s spectacular wildlife and launched her own company, Lamar Valley Touring, based in Gardiner, Montana.

We’re on one of her tours that morning at Yellowstone. As we watch, the hunting scene in front of us escalates. The wolves single out a parentless calf and give chase. The calf gallops, the wolves circle, the calf turns back, skids, careens, loses speed—but just as one wolf leaps for the kill, a huge bull cuts in between. The wolves miss. “Poor things, now they’ll go hungry,” we say as the foursome leaves the battlefield. After everything we’ve learned about their role in the ecosystem, we now see the importance of a successful hunt.

“They are used to being hungry,” Taylor says, adding that wolves are resilient and adaptable. “Most hunts aren’t successful. These four look young. They’re juveniles, so it’s not surprising they missed.”

Wolves occupy a special place in Taylor’s heart. “They’re so incredibly misunderstood and so incredibly parallel to us humans,” she says. A wolf pack is a family unit, sometimes with “friends” who join in for genetic diversity, “because wolves are too smart to interbreed,” she says. Packs usually have an alpha male and an alpha female, who sire pups, some of which may stay with the pack while others may leave. Sometimes, a pack is run by an old matriarch, a grandma who keeps pups in check. Sometimes more than one female in a pack gives birth, so they rear the pups together, taking turns babysitting. Young female or male wolves may babysit, too, just like older human cousins do.

Although protected inside Yellowstone, wolves can be hunted once they leave the park. In 2022, NPR reported that a record number of wolves were shot outside the park—25, which amounted to 20 percent of the wolf population. In 2025 so far, about 10 wolves that ventured beyond Yellowstone’s borders have been killed. Although the park rangers and biologists aren’t yet sure of the exact numbers, they no longer see the pack members they used to see, says Rick McIntyre. McIntyre is a world-famous wolf expert and author of a book series about Yellowstone wolves, including Thinking Like a Wolf, which features Taylor’s work. McIntyre started working for the U.S. National Park Service in 1975 and specifically at Yellowstone in 1994, where his responsibilities included explaining the wolf reintroduction program to visitors and studying the animals.

Over the years, McIntyre has had over 100,000 sightings of wolves—more than any other person in history. “I’m out with the wolves every day, and I have seen so much over the years,” he says. He’s watched wolves wage wars over territory, form lifelong partnerships, risk their lives by leading enemy packs away from their offspring, and die in battle to save their pups.

Taylor’s work advocating for wolves involves educating people about wolves’ importance to the ecosystem and their characters. But she feels that sometimes human animosity toward wolves runs too deep to mend, particularly with farmers and ranchers who believe that wolves threaten their cattle. “I’ve never had a rancher or a farmer on a tour with me,” she says. “They don’t want to talk to me. I’ve been advocating for 12 years now; they don’t care.”

McIntyre says he understands ranchers and farmers who retaliate when they believe wolves take or threaten their cattle. “I am sympathetic to their situation,” he says, because they put a lot of work into raising the animals, and losses affect their business. “So if it’s a rancher that feels, rightly or wrongly, that wolves have killed some sheep or calves, I can understand how they would feel that way.”

But Taylor says people sometimes kill wolves just for fun. She shares a story of the Lamar Canyon pack, whose matriarch was killed in 2018. “She used to keep watch on the pups and their older ‘teen’ siblings while their parents went hunting,” Taylor says. But a local hunter had been stalking her for months and finally caught her when she wandered about a mile outside the park. “I was burying her scat and covering her tracks, trying to keep the hunter from finding her,” Taylor says. But he was determined. “He wound up getting her when I wasn’t around.”

He brought her body back to his house, and her grandchildren followed the scent all the way to town, Taylor says. Upset and distraught, they were howling nearby. “They knew she was there, and they were howling and crying,” she says. Eventually they killed someone’s dog, which only brought more wrath to their pack, which eventually disbanded. “I think a couple of them wound up getting killed because they were out of the park,” Taylor says. “Basically, because he killed the matriarch, the entire pack fell apart.”

Notably, living wolves are worth a lot more than dead ones—to their packs, to ecosystems, and even to human livelihoods. “Having wolves in Yellowstone is contributing $82 million to our local economy, because people come to Yellowstone to see the wolves,” McIntyre says. “So that’s $82 million to the local businesses, which obviously creates a lot of jobs for people.”

For Taylor, it’s simply the joy of watching the animals form families, have pups, and raise their young year after year that makes it worthwhile. “I love watching wolves just being wolves,” she says. “And I love showing people how much humans and wolves have in common.”

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)