'Brokeback Mountain' at 20: How Ang Lee’s Queer Cowboy Classic Changed Cinema

Ang Lee inspired a generation of filmmakers, but his queer cowboy classic remains a peerless masterpiece.

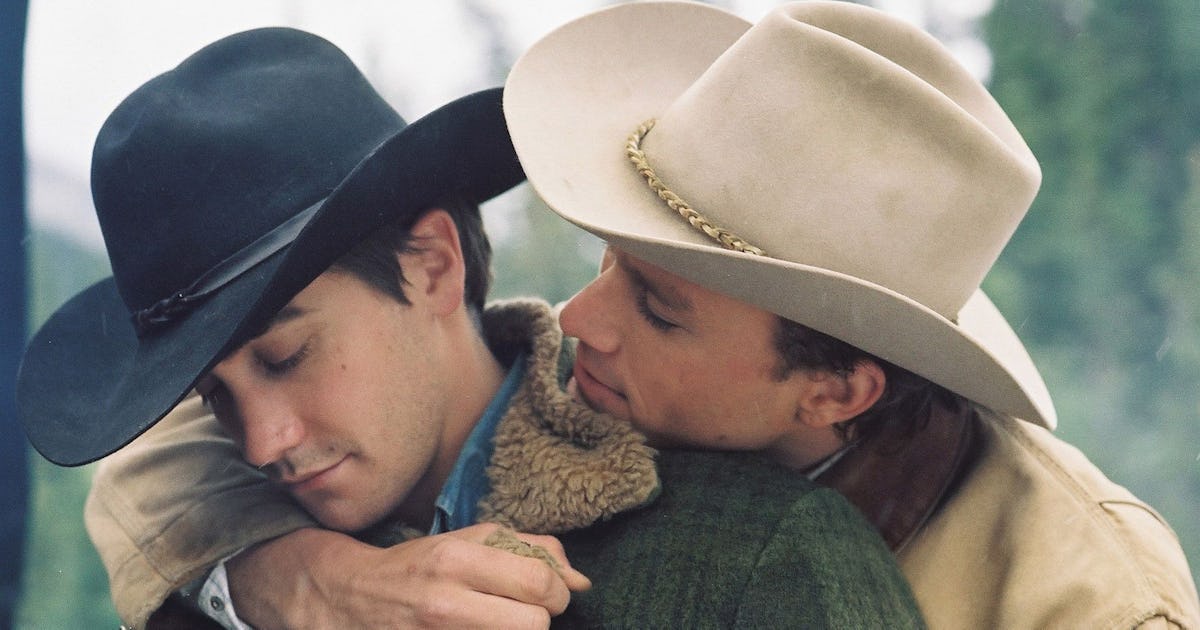

Whenever I see a checkered Western shirt, I immediately imagine it with a bloodied sleeve. Thanks to its role in Brokeback Mountain, Ang Lee’s seminal work of queer cinema, I can’t help it. It’s one of the first things we see in the film, worn by stoic Ennis Del Mar (the late Heath Ledger) while herding sheep with his fellow ranch hand and soon-to-be secret lover, Jack Twist (a never-better Jake Gyllenhaal). It’s also one of the last, in a scene that takes place two decades later, when Jack has died and Ennis finds the long-forgotten garment, pristine and untouched, hanging inside his former paramour’s childhood bedroom closet.

Slung atop the denim button-up Jack wore while with him on the titular hill, Ennis’s simple shirt, its cuff stained red from a violent altercation, becomes a symbol of his ill-fated union; like their tops, the pair are forever entwined—but only out of sight, forced to hide in the back of a closet. It’s a striking image, especially as Ennis, tears welling up in his eyes, gazes longingly at both pieces as the credits begin to roll. What was once his now feels like the last vestige of a man who swung into his life and completely shifted his worldview.

I’ve been thinking about that scene since Brokeback Mountain muscled its way into theaters 20 years ago, unexpectedly becoming a hit in a country still a decade removed from voting to legalize gay marriage. Based on the 1997 short story by Annie Proulx, Lee’s “gay cowboy movie” (as it was referred to by both admirers and adversaries alike) couched a homosexual romance into one of cinema’s most stereotypically masculine genres. It’s also a profound meditation on the hazards of repression, and a deep-felt exploration of the simultaneous danger and delight of recognizing a shameful part of yourself in another. (Watching it for the first time, it struck a chord at a young age when I, too, had resigned myself to staying in the closet forever.)

Today, Brokeback Mountain maintains its prominent place in the public consciousness. 20 years post-release, it’s still invoked as a shorthand for any movie about two men falling in love. (Just ask Paul Mescal.) Though it wasn’t the first LGBTQ+ film to break through to the mainstream, it was certainly one of the earliest capital-D dramas to do so. This wasn’t a light farce in the style of Mike Nichols’s The Birdcage; this was a serious film for serious adults. It had real thematic heft. It was also defiantly gay. In direct contrast to, say, Tom Hanks’s 1993 AIDS drama Philadelphia, Lee’s opus made no appeals to straight audiences. Despite its portrayal of men stuck in the closet, nothing about Brokeback’s devastatingly stark realism felt pandering.

In a different world, these roadblocks would’ve been the death knell for a small indie film fighting for attention. In fact, many initially wrote it off as a niche release. Conservatives and (conservative) Christians even upheld it as proof of their ongoing belief that the hyper-liberal “Hollywood elite” was painfully out of touch with the good-natured ideals of America’s heartland.

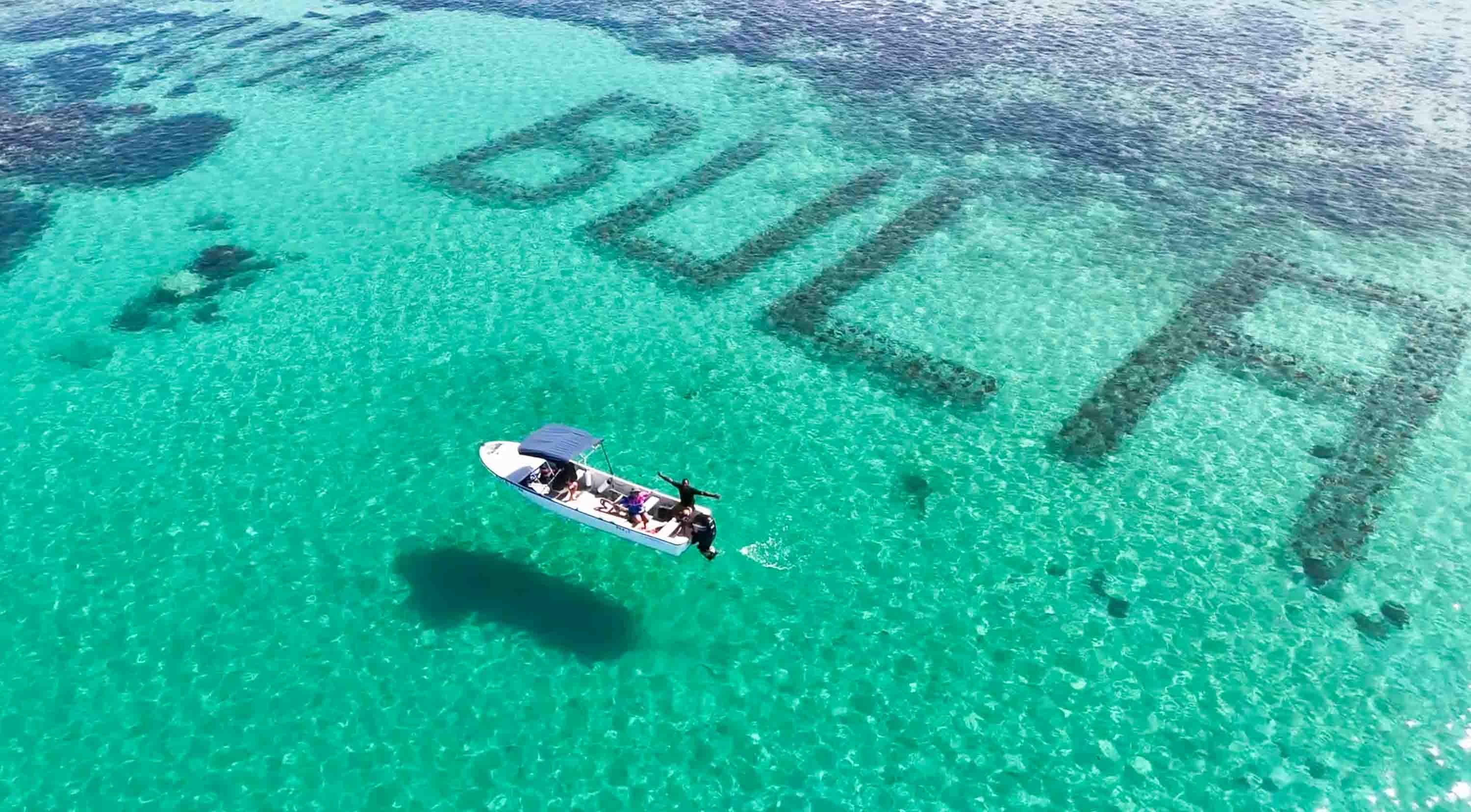

Unfortunately for them, Brokeback was a work of undeniable brilliance. No self-respecting cinephile could ignore Lee’s characteristically sensitive direction or the buffet of sweeping vistas captured through Rodrigo Prieto’s cinematography. Then, there were Gyllenhaal and Ledger, two proven stars who dared to play gay during an era when doing so could be career suicide (and not a fast track to awards consideration). Their participation elevated the film’s profile; their performances, achingly raw, rendered their characters’ suffocating pain visceral.

And so, against all odds, Brokeback, far from the sanitized and chaste depiction of gay culture one would expect to crossover, concluded its run as both a commercial and critical success. The love for it remains so strong that, despite winning three Oscars (for Director, Adapted Screenplay, and Score), many still cite its loss to the controversy-ridden Crash in Best Picture as one of the most egregious in Oscars history. (To date, it’s the only film to not win the top prize after sweeping through the triumvirate of DGA, PGA, and WGA.) Even Crash director Paul Haggis has admitted that he wouldn’t have voted for his own film to take home that trophy.

Two decades on, LGBTQ+ films have become increasingly commonplace. (Even the Academy has evolved, giving Best Picture to Moonlight in 2017.) And yet, Brokeback still feels like an outlier. Just think of Prieto’s camera zooming in as Ennis spits in his hand to lube Jack up before penetrating him from behind. After eons of gay sex being treated as a faux pas, Lee’s film set a new precedent by being about gay sex, about the ways unearthing a long-buried desire could be both eye-opening and soul-crushing. In Brokeback, it was a yearning like any other.

But its prescience extends beyond that. What has crystallized over time is how much Brokeback had always been in direct conversation with the very culture it was released into. Though it was set almost 40 years in the past, it seemingly anticipated the finger-wagging admonishment it would receive in the present. With his trademark humanism, Lee crafted an otherwise universal love story around the dispiriting premise that a clandestine affair was the best that two men enamored with each other could ever hope for. Then, by emphasizing the ever-present magnetized force that kept drawing Jack and Ennis back together, despite the dangers associated with such unions, Brokeback forced audiences to consider whether there was any real cultural (or moral) good in working to keep them—or, real-world people like them—apart.

The vicissitude of its tragic storytelling was by design. Ennis is increasingly tortured by the unavoidable desires he feels forced to keep hidden, and this inner battle manifests in alcohol abuse, spousal infidelity, and estrangement from his children. But what if he could follow his heart instead, the film asks its audience. If he could take Jack up on his offer to get “a little ranch somewhere” and be together, could Ennis’s fate be circumvented? If Jack wasn’t forced to hunt down-low trade when Ennis was unavailable to him, would he still be alive today?

In the ensuing years, there have certainly been attempts to capture that same intricate mix of human sensitivity and righteous anger. The agony of losing a first love is stamped all over the smooth sensuality of Luca Guadagnino’s Call Me By Your Name. Moonlight treads similar territory from a racialized perspective. The Power of the Dog, Jane Campion’s take on the “repressed gay cowboy film,” even repeated Brokeback’s unfortunate Oscar trajectory.

But Brokeback paved the way. At a time when queer narratives were still embarrassingly rare in the mainstream, Lee’s western melodrama awakened an appetite in audiences starving for real, raw representation—and today, in an age where “queerness” has itself become a mainstream identity marker, it still rings peerless. So, as the film crosses the two-decade threshold, I can only hope for two more. In the immortal words of Jack Twist, “I wish I knew how to quit you.”