Søren Skarby’s "Scaled Up" project: The stunning, ultra-detailed world of fish

A Longspined Bullhead. Click here to experience the full-size image. Image: Søren Skarby Combining work with hobbies can be a risky endeavor. Søren Skarby, a photojournalist and passionate fly fisherman, endeavored for years to keep photography – his profession – and fishing – his hobby – separate. But inevitably, the two worlds collided. The result was a long-term, ongoing project named Scaled Up, which aims to document fish with a level of detail we don't usually see. Skarby took the time to chat with me about his series, providing insight into what led to the project and the complicated process behind it. "We think of fish in this part of the world as something dull. But fish are very colorful" Skarby often has the experience of catching a fish and thinking how beautiful it is. Other people didn't quite get it when he would tell them, though. "We think of fish in this part of the world as something dull. But fish are very colorful as you can see, even in Scandinavia," he explained. Plus, most people only come across fish after it's processed and in the supermarket, which is always colorless. Seeing the fish alive is a totally different experience, and he wanted to figure out a way to show others the beauty he saw while fishing. A Common Dragonet. Click here to experience the full-size image. Photo: Søren Skarby When he saw the Microsculpture series of insect photographs by Levon Biss, it was a turning point. Skarby decided he wanted to do something similar with fish by combining hundreds of images taken with a high-resolution camera to create uber-high-resolution photos. From the start, he knew he would need funding. "If I'm going to do this right, I've got to get paid while I'm thinking because I'll only be focusing on that," he said. So he reached out to a museum to collaborate, and they were eager to participate. Obtaining funding took time, but it did eventually come. While the idea of photographing fish is simple at face value, it's actually quite complicated. "I came up with one idea after the other and ditched it because it didn't work," Skarby explained. While most fish are colorful while alive, they lose that color very quickly when they die. So you have a very short window to work. Skarby says that cod is the worst, as it will turn very dark in less than 10 minutes. He started working with a taxidermist, and together they figured out that baby oil would prolong the time they had to photograph the specimen before the color drained. A female trout. Click here to experience the full-size image. Photo: Søren Skarby Next, Skarby said he had to figure out how to manage the camera setup. His process involves a combination of focus stacking and panoramic stitching to maximize the level of detail. But that presented its own set of problems. "It's really, really hard to set up a camera vertically and then move it and keep the same distance to the subject all the way. There's no gear made for it," he said. He was venting his frustrations to a friend, who said, "Can't you move the fish?" It was a lightbulb moment, and they drew the idea on the drywall of his mid-renovation kitchen, eventually having a movable table made for the project. Lighting was the next hurdle. Skarby tried using constant light but said the exposure time gets way too long. He explained that the image he created of the male Three-Spined Stickleback took 40 minutes total, with each exposure lasting 15 seconds. Every time a loud motorcycle or large truck drove past their studio, they got nervous, because they were sure it would shake the camera or table with the fish and ruin the image. Flash, then, is a must, but it has to be precise flash that fires consistently each time. A male Three-spined Stickleback. Click here to experience the full-size image. Photo: Søren Skarby His lighting setup is relatively simple, with a light under the glass on which the fish rests and a light above at a 45-degree angle. However, the highly reflective surface of the baby oil-covered fish introduces challenges with lighting. So, Skarby adds polarizing filters to everything, including both lights and the camera lens. Finding an ideal polarizer for the lights was yet another moment of creative problem-solving. Eventually, Skarby realized that TFT displays used in TVs have polarizing filters inside, and that he could buy packs of the filters meant for large TVs directly from China for cheap. Those filters then go in front of the softbox, and when one needs to be replaced, it isn't a big cost to replace it. A Garfish. Click here to experience the full-size image. Photo: Søren Skarby The studio setup isn't the end of challenges, either. Skarby ends up with between 120 and 440 individual images for each fish. He goes through each Raw file before starting the stitching process, and then spends an extensive amount of time retouching at 200% or even 300% once the files are stitched together. For example, the im

|

|

A Longspined Bullhead. Click here to experience the full-size image. Image: Søren Skarby |

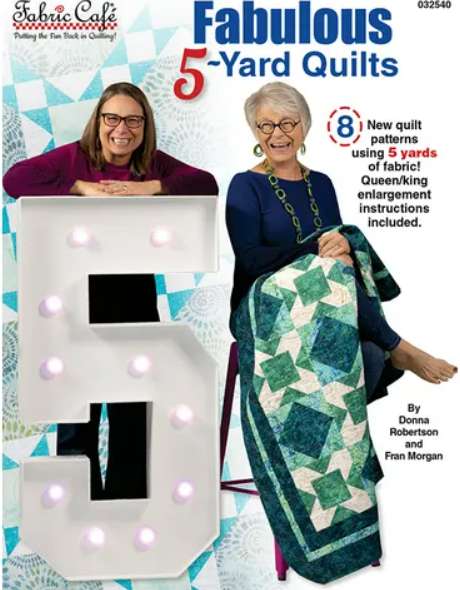

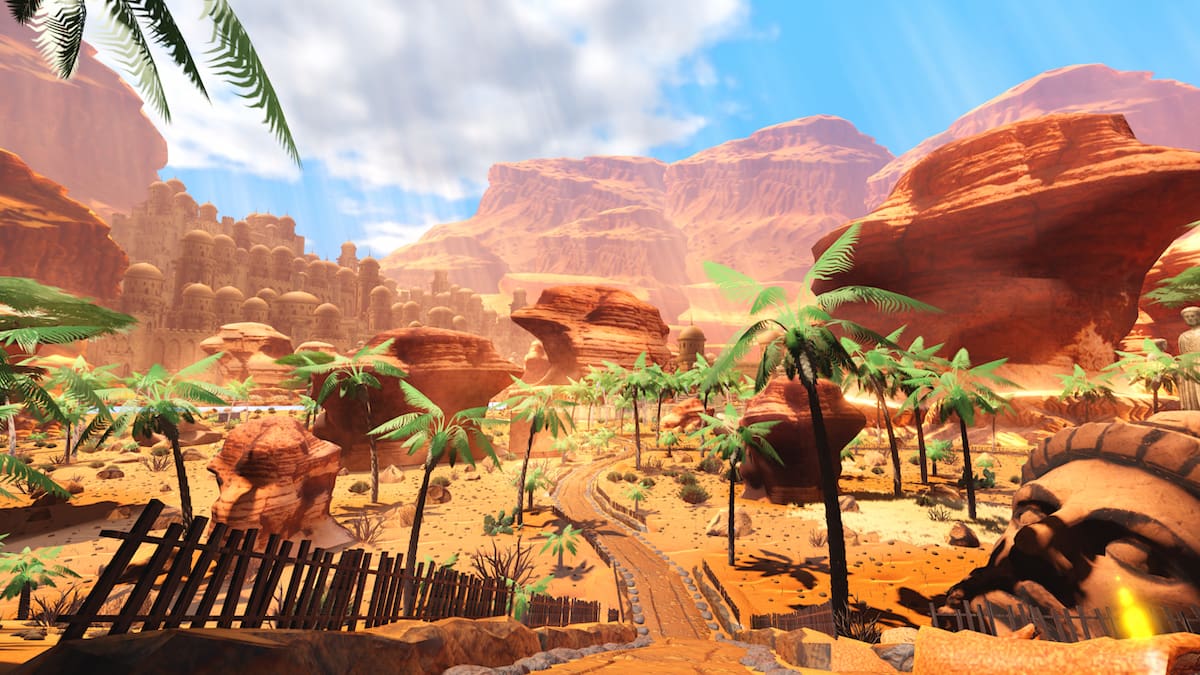

Combining work with hobbies can be a risky endeavor. Søren Skarby, a photojournalist and passionate fly fisherman, endeavored for years to keep photography – his profession – and fishing – his hobby – separate. But inevitably, the two worlds collided. The result was a long-term, ongoing project named Scaled Up, which aims to document fish with a level of detail we don't usually see. Skarby took the time to chat with me about his series, providing insight into what led to the project and the complicated process behind it.

"We think of fish in this part of the world as something dull. But fish are very colorful"

Skarby often has the experience of catching a fish and thinking how beautiful it is. Other people didn't quite get it when he would tell them, though. "We think of fish in this part of the world as something dull. But fish are very colorful as you can see, even in Scandinavia," he explained. Plus, most people only come across fish after it's processed and in the supermarket, which is always colorless. Seeing the fish alive is a totally different experience, and he wanted to figure out a way to show others the beauty he saw while fishing.

|

|

A Common Dragonet. Click here to experience the full-size image. Photo: Søren Skarby |

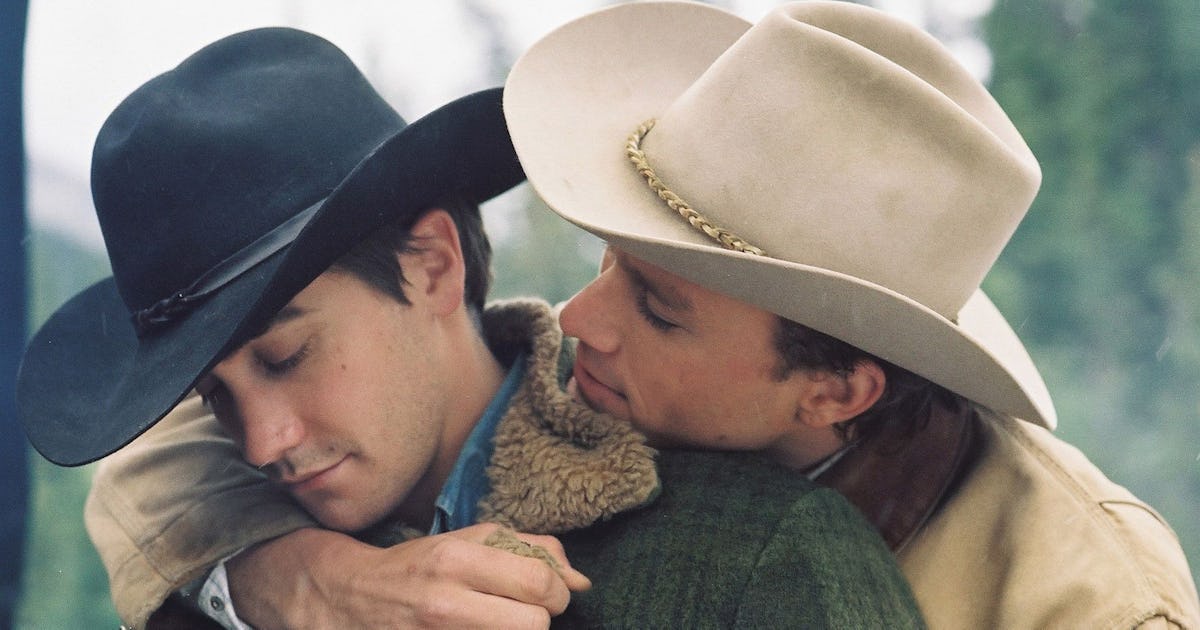

When he saw the Microsculpture series of insect photographs by Levon Biss, it was a turning point. Skarby decided he wanted to do something similar with fish by combining hundreds of images taken with a high-resolution camera to create uber-high-resolution photos. From the start, he knew he would need funding. "If I'm going to do this right, I've got to get paid while I'm thinking because I'll only be focusing on that," he said. So he reached out to a museum to collaborate, and they were eager to participate. Obtaining funding took time, but it did eventually come.

While the idea of photographing fish is simple at face value, it's actually quite complicated. "I came up with one idea after the other and ditched it because it didn't work," Skarby explained. While most fish are colorful while alive, they lose that color very quickly when they die. So you have a very short window to work. Skarby says that cod is the worst, as it will turn very dark in less than 10 minutes. He started working with a taxidermist, and together they figured out that baby oil would prolong the time they had to photograph the specimen before the color drained.

|

|

A female trout. Click here to experience the full-size image. Photo: Søren Skarby |

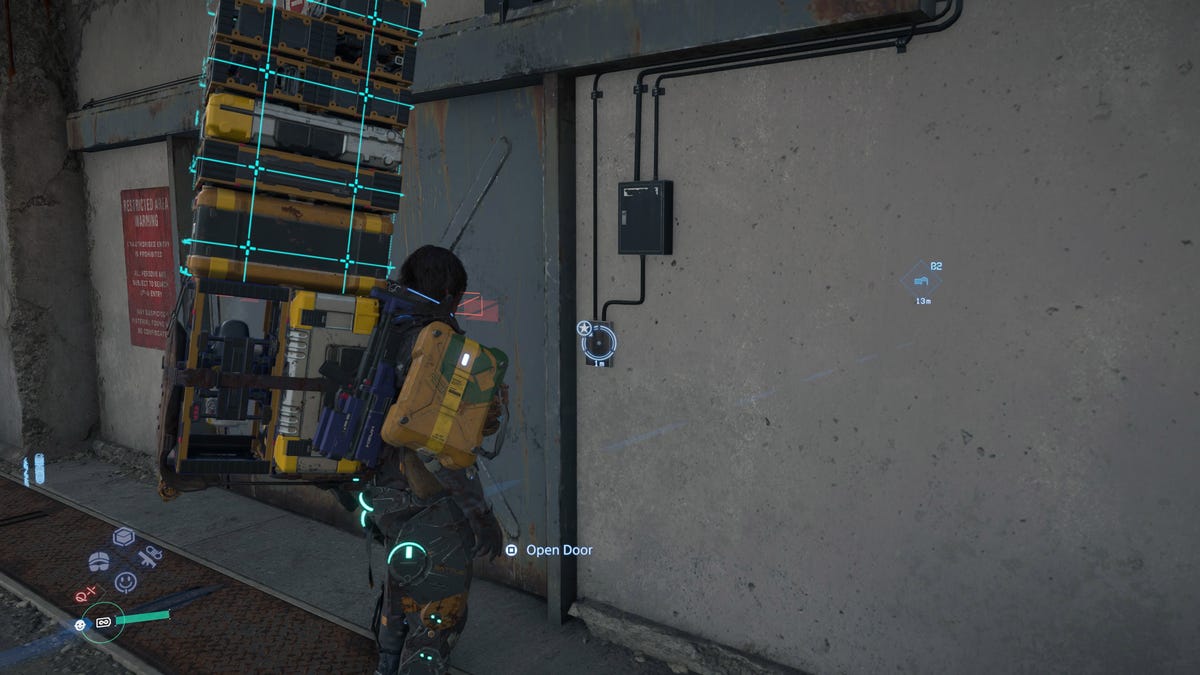

Next, Skarby said he had to figure out how to manage the camera setup. His process involves a combination of focus stacking and panoramic stitching to maximize the level of detail. But that presented its own set of problems. "It's really, really hard to set up a camera vertically and then move it and keep the same distance to the subject all the way. There's no gear made for it," he said. He was venting his frustrations to a friend, who said, "Can't you move the fish?" It was a lightbulb moment, and they drew the idea on the drywall of his mid-renovation kitchen, eventually having a movable table made for the project.

Lighting was the next hurdle. Skarby tried using constant light but said the exposure time gets way too long. He explained that the image he created of the male Three-Spined Stickleback took 40 minutes total, with each exposure lasting 15 seconds. Every time a loud motorcycle or large truck drove past their studio, they got nervous, because they were sure it would shake the camera or table with the fish and ruin the image. Flash, then, is a must, but it has to be precise flash that fires consistently each time.

|

|

A male Three-spined Stickleback. Click here to experience the full-size image. Photo: Søren Skarby |

His lighting setup is relatively simple, with a light under the glass on which the fish rests and a light above at a 45-degree angle. However, the highly reflective surface of the baby oil-covered fish introduces challenges with lighting. So, Skarby adds polarizing filters to everything, including both lights and the camera lens.

Finding an ideal polarizer for the lights was yet another moment of creative problem-solving. Eventually, Skarby realized that TFT displays used in TVs have polarizing filters inside, and that he could buy packs of the filters meant for large TVs directly from China for cheap. Those filters then go in front of the softbox, and when one needs to be replaced, it isn't a big cost to replace it.

|

|

A Garfish. Click here to experience the full-size image. Photo: Søren Skarby |

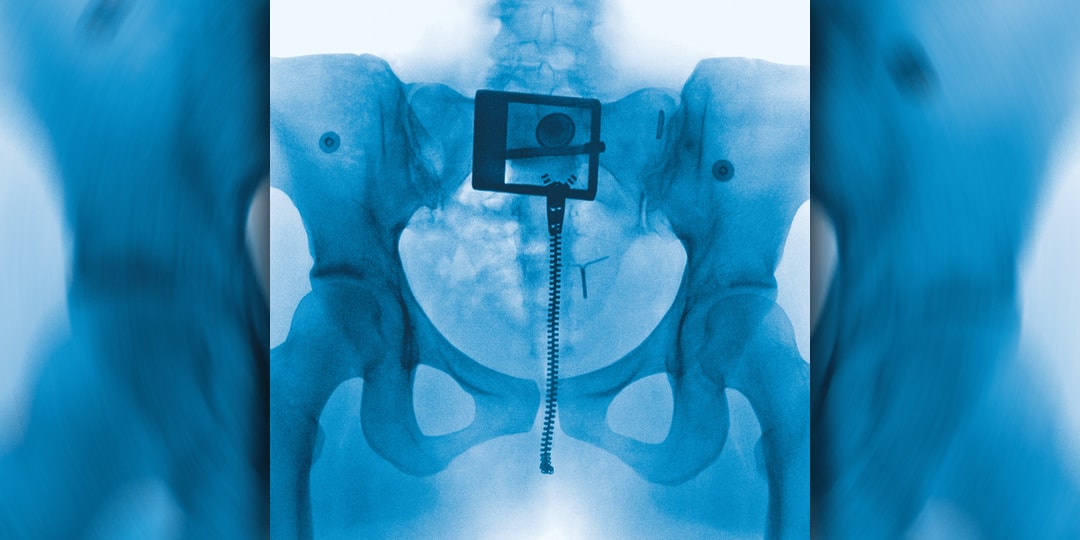

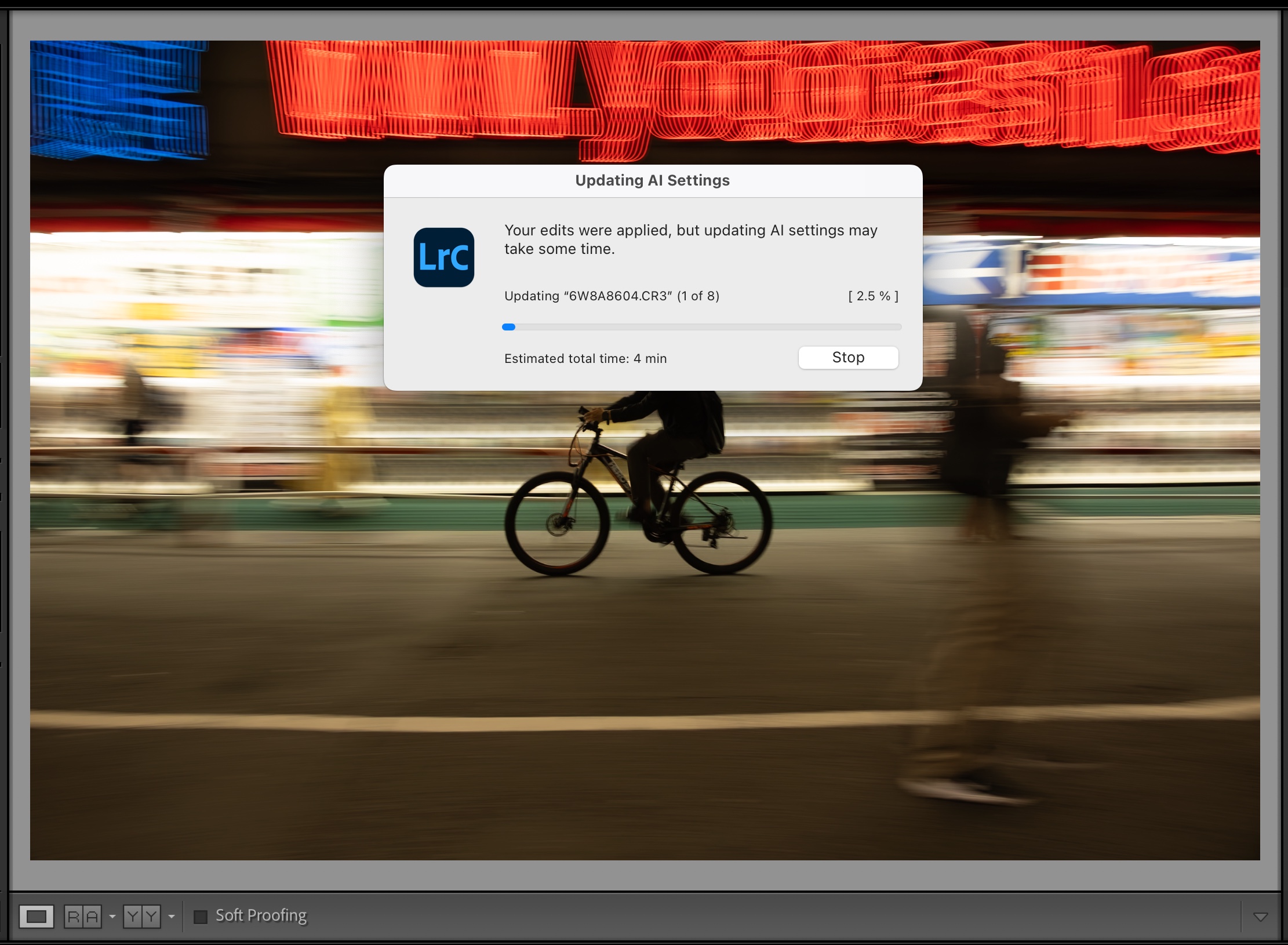

The studio setup isn't the end of challenges, either. Skarby ends up with between 120 and 440 individual images for each fish. He goes through each Raw file before starting the stitching process, and then spends an extensive amount of time retouching at 200% or even 300% once the files are stitched together. For example, the image he created of the Gar, which is 52,500 pixels long, took 80 hours to Photoshop. Each image has loads of dust to remove, along with the edges of the glass pieces used to spread out fins and keep the fish in position.

|

|

This unretouched image shows just how much work is involved in the retouching process. The final image can be seen here. Photo: Søren Skarby |

While the Scaled Up project has been running since 2019, Skarby is far from done. He's currently working on his largest round of grant funding and plans on building out a caravan to be a mobile studio. That includes a camera stand that is built into the vehicle instead of using a tripod.

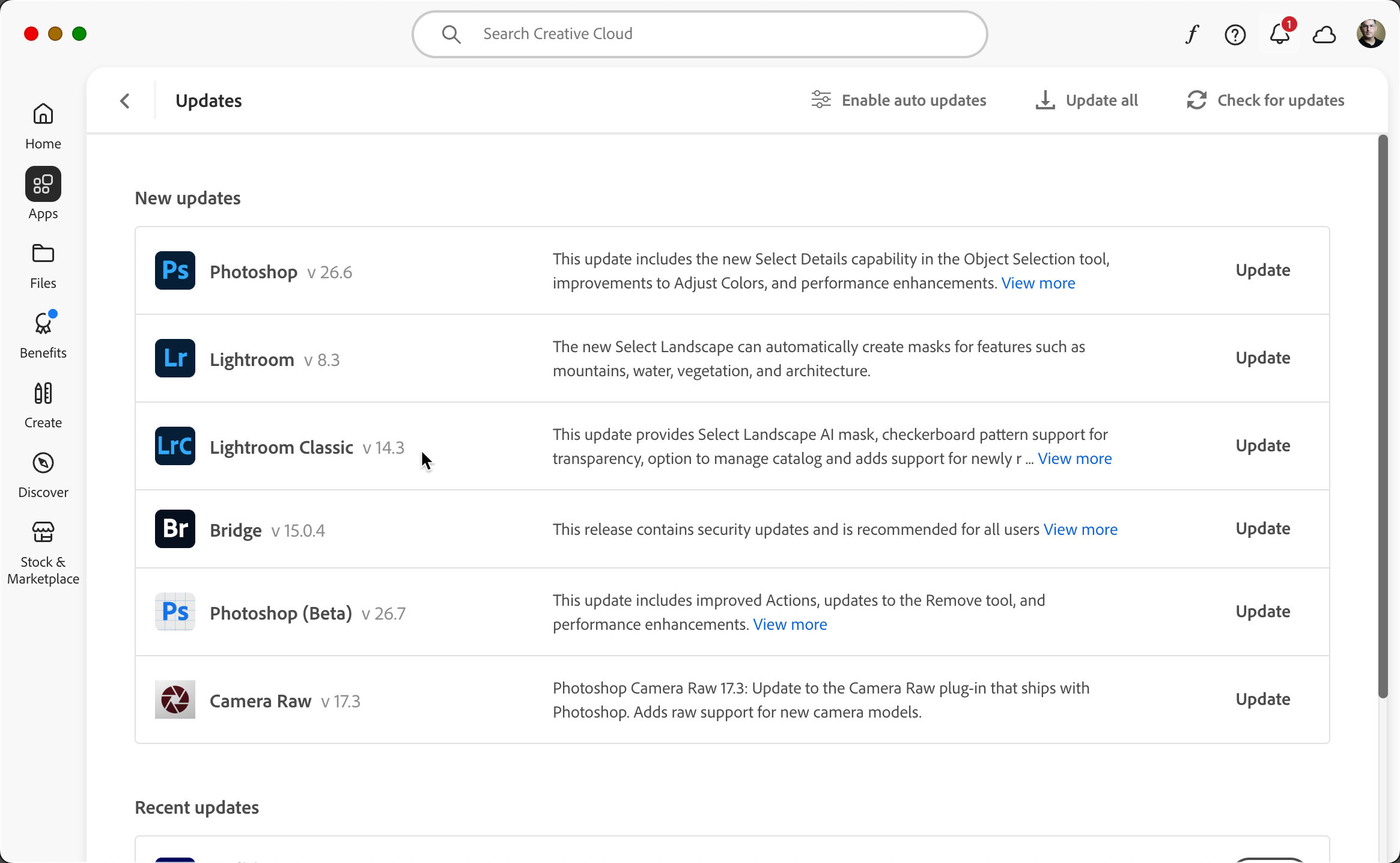

The caravan studio will enable him to go where the fish are, and connect with more people to curate stories with each individual fish. He's also going to be switching from the Fujifilm GFX 50S to a Phase One camera system, and using Helicon software for stacking the images instead of Photoshop. He says those changes should make the process somewhat easier and faster.

|

|

A Snake Pipefish. Click here to experience the full-size image. Photo: Søren Skarby |

Beyond the technical side of things, Skarby says there are also concerns related to conservation and ethics. After all, the fish aren't alive when he photographs them. He was recently offered the opportunity to photograph the European sprat, which is endemic to Denmark. While he was honored, that fish is incredibly rare, so he turned it down. "It would be crazy to say that 'we want you to be aware of the wild tiger and that’s why we’ve shot one to show to you,'" he said.

"What I'm trying to do with the pictures is showing people this is what you risk losing."

Skarby says that one of the reasons this project is so important is for conservation reasons. "I don't know what I am any more, if I'm a fly fisher, photographer or both or I'm actually an environmentalist," he says. No matter what he is, he's using the images to raise awareness and help bring attention to the unexpected beauty of certain fish. "What I'm trying to do with the pictures is showing people this is what you risk losing."

We aren't able to show off Skarby's images at full resolution, so if you want to see these fish in all their glory, be sure to head to his website. There, you'll be able to zoom in to remarkable levels, highlighting spectacular details on each fish.

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)