Schieks Cave Below Minneapolis Contains a Lake of Warm Sewage

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. Dylan Thuras: Hidden beneath the streets of Minneapolis lies a strange geologic anomaly. It’s called Schieks Cave. Above the cave, the city is alive, full of vitality and character. The glow from buildings casts shadows over the streets. The skyline blends old-world charm with modern design. Traffic hums, buildings tower, but deep below all of that, there’s a secret buried down there. Access to it lies deep below the street. What appears as a simple manhole cover leads to an entirely different world down below. Greg Brick: It’s a perfect maze underlying a full city block. Dylan: Greg Brick, an urban explorer and longtime Minneapolis resident, as was I once, had known about the cave for years. Greg: It was just the sense of remoteness. You got this cave 75 feet below street level, with a well-known history dating back to 1904, and nobody that I was aware of had been there. Dylan: The manhole cover was a gateway inside. However, as much as the city wanted to keep it secret, Greg Brick knew it was there and was desperate to get inside. I’m Dylan Thuras, and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Greg’s first attempt, it led to a dead end. Back in 2000, back, in fact, when I was a senior in high school in Minneapolis, Greg was also there finding his way inside this cave. And when he got in there, he made a shocking discovery. This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. Dylan: Greg Brick was obsessed. For years, he had sifted through old newspaper articles, exploring the history of this cave. He turned to old guidebooks, trying to find something, anything, about the history of this cave. Greg: They published a long historical section about the cave with historic photographs from the time it was discovered in 1904, its maps, and so it was a known entity. Dylan: The cave was originally discovered by a Minneapolis sewer engineer in 1904, but the city decided that they should keep the cave a secret. They did not want people thinking that the city was built on empty, unstable ground. And in 1929, the city reinforced the area with walls and piers and artificial drainage systems. That certainly didn’t make it any easier to get into this cave. So Greg had to think creatively. Greg: When I wanted to go in the cave, I couldn’t go in the city and ask them, I had to find my own way in. Dylan: It was not an easy project, and he had several failed attempts. Greg: I got pretty close in the ’90s. Dylan: But in 2000, Greg and his buddy made a major breakthrough. Greg: We were down there walking around in the storm drains, then we noticed that the floor of a sanitary sewer had collapsed. And that if you went through that break, then you had access to Schieks Cave after a little while. Dylan: And crawling through the gap, suddenly, he was in. As Greg moved deeper into the cave, he was hit with a unique smell, a smell of sandstone and water and earth. It didn’t smell bad, it just smelled like being deep underground. He reached for his flashlight, and when he turned it on, he was suddenly struck speechless. The walls were lined with decades of natural carvings, just little grooves and marks that had been made by the constant flow of water over time. But there was more down there. There were roaches scurrying all around. There was a pasta plate full of earthworms wriggling around across the cave floor. Weirdly, there were plastic straws scattered around the space too. It wasn’t necessarily a space you would call charming. But for an urban explorer like Greg, this was his bread and butter. Greg: Some of the things that turn people off about Schieks cave is actually what made it fascinating to me. Dylan: But among all the other sights, there was something down there that Greg was not expecting, and in fact, definitely did not want to find: raw sewage. The smell was no longer quite so nice. Greg: It formed a substantial lake about 100 feet across that we called the Black Sea. It was about this knee-deep black fluid that was actually raw sewage that was going in there to bubble and ferment. Dylan: Greg was not just your average urban explorer. He is a hydrogeologist as well, which means that he studies how groundwater moves through the soil and the rock. So instead of being just completely grossed out and running away, Greg decided to explore a little more deeply. And among the muck and the gunk, he spotted something else surprising, a little subterranean waterfall. Greg: What it actually was was what a hydrologist or hydrogeologist would call a ceiling spring. So this is groundwater pouring out of a crevice in the ceiling. And so it was about six feet high. Dylan: And in good hydrogeologist form, Greg decided he needed to kno

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Dylan Thuras: Hidden beneath the streets of Minneapolis lies a strange geologic anomaly. It’s called Schieks Cave. Above the cave, the city is alive, full of vitality and character. The glow from buildings casts shadows over the streets. The skyline blends old-world charm with modern design. Traffic hums, buildings tower, but deep below all of that, there’s a secret buried down there. Access to it lies deep below the street. What appears as a simple manhole cover leads to an entirely different world down below.

Greg Brick: It’s a perfect maze underlying a full city block.

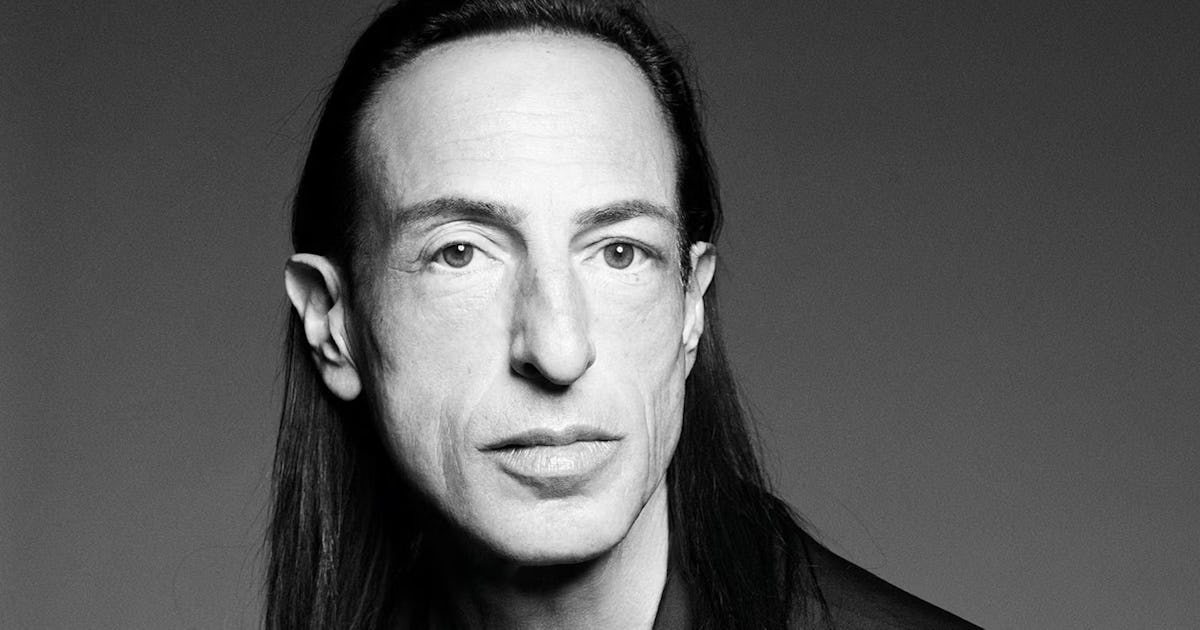

Dylan: Greg Brick, an urban explorer and longtime Minneapolis resident, as was I once, had known about the cave for years.

Greg: It was just the sense of remoteness. You got this cave 75 feet below street level, with a well-known history dating back to 1904, and nobody that I was aware of had been there.

Dylan: The manhole cover was a gateway inside. However, as much as the city wanted to keep it secret, Greg Brick knew it was there and was desperate to get inside. I’m Dylan Thuras, and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Greg’s first attempt, it led to a dead end. Back in 2000, back, in fact, when I was a senior in high school in Minneapolis, Greg was also there finding his way inside this cave. And when he got in there, he made a shocking discovery.

This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Dylan: Greg Brick was obsessed. For years, he had sifted through old newspaper articles, exploring the history of this cave. He turned to old guidebooks, trying to find something, anything, about the history of this cave.

Greg: They published a long historical section about the cave with historic photographs from the time it was discovered in 1904, its maps, and so it was a known entity.

Dylan: The cave was originally discovered by a Minneapolis sewer engineer in 1904, but the city decided that they should keep the cave a secret. They did not want people thinking that the city was built on empty, unstable ground. And in 1929, the city reinforced the area with walls and piers and artificial drainage systems. That certainly didn’t make it any easier to get into this cave. So Greg had to think creatively.

Greg: When I wanted to go in the cave, I couldn’t go in the city and ask them, I had to find my own way in.

Dylan: It was not an easy project, and he had several failed attempts.

Greg: I got pretty close in the ’90s.

Dylan: But in 2000, Greg and his buddy made a major breakthrough.

Greg: We were down there walking around in the storm drains, then we noticed that the floor of a sanitary sewer had collapsed. And that if you went through that break, then you had access to Schieks Cave after a little while.

Dylan: And crawling through the gap, suddenly, he was in. As Greg moved deeper into the cave, he was hit with a unique smell, a smell of sandstone and water and earth. It didn’t smell bad, it just smelled like being deep underground. He reached for his flashlight, and when he turned it on, he was suddenly struck speechless. The walls were lined with decades of natural carvings, just little grooves and marks that had been made by the constant flow of water over time. But there was more down there. There were roaches scurrying all around. There was a pasta plate full of earthworms wriggling around across the cave floor. Weirdly, there were plastic straws scattered around the space too. It wasn’t necessarily a space you would call charming. But for an urban explorer like Greg, this was his bread and butter.

Greg: Some of the things that turn people off about Schieks cave is actually what made it fascinating to me.

Dylan: But among all the other sights, there was something down there that Greg was not expecting, and in fact, definitely did not want to find: raw sewage. The smell was no longer quite so nice.

Greg: It formed a substantial lake about 100 feet across that we called the Black Sea. It was about this knee-deep black fluid that was actually raw sewage that was going in there to bubble and ferment.

Dylan: Greg was not just your average urban explorer. He is a hydrogeologist as well, which means that he studies how groundwater moves through the soil and the rock. So instead of being just completely grossed out and running away, Greg decided to explore a little more deeply. And among the muck and the gunk, he spotted something else surprising, a little subterranean waterfall.

Greg: What it actually was was what a hydrologist or hydrogeologist would call a ceiling spring. So this is groundwater pouring out of a crevice in the ceiling. And so it was about six feet high.

Dylan: And in good hydrogeologist form, Greg decided he needed to know a little more. He simply could not resist measuring the water temperature.

Greg: And I found out that it was elevated 20 degrees above the expected groundwater temperature for Minneapolis.

Dylan: This was a problem. The water was way, way too hot.

Greg: The groundwater in Minneapolis is actually at the temperature of Jackson, Mississippi.

Dylan: Something was warming the water below Minneapolis, making it as warm as the water you would find in the sweltering South. But this was way up in the cold Midwest. Water like that was not supposed to be happening.

Greg: I mean, this is like the most unusual groundwater phenomenon that I’ve come across in the state of Minnesota. And it has public health implications.

Dylan: Greg returned to the cave again to retest his findings, and the results were the same. The closer he measured to the surface, the warmer the water got. It turns out back in 2008, a team of researchers from the University of Minnesota had predicted that heat from the urban surface, the streets and buildings themselves, was seeping deep underground, essentially heating the groundwater up in a giant metropolitan microwave. And when Greg journeyed down into the cave and discovered this weirdly warm groundwater, he ended up confirming this team’s suspicions. Greg’s exploration had been sparked out of mere curiosity, but he was starting to think that this whole thing could have consequences. Here is what he thought was going on: In many cities, including my hometown of Minneapolis, the pipes, the infrastructure is all getting pretty old. And so sewage occasionally starts to leak out of them, which means that all of that bacteria starts to get into the ground. And then there is warm groundwater in the surrounding area. And in all of that warm water, the bacteria multiplies, increases quickly. And then you’ve got this warm water full of bacteria, and it can be sucked back into the pipes, back into your house, out of the faucet. So this was not a major crisis or a looming catastrophe, but more like a low, unsettling hum. You know, little increases in gastrointestinal issues, maybe not a life-threatening problem, but not ideal. So Greg reached out to local Minneapolis authorities and energy companies to talk to them about the problem, but the response was not what he hoped for.

Greg: When I talk about the warm groundwater, it’s like, oh, okay, yeah, I accept that. But they don’t get it because they’re not experts in that exact field.

Dylan: So Minneapolis has this problem. It’s got a cave beneath its streets. The cave is filled with warm water, and that warm water is full of sewage. It may be cold comfort, but Minneapolis is not alone. It’s a problem that other cities around the world have encountered. Across Europe, across Canada, researchers have even explored recycling some of that underground heat, using it as an energy source, like a heat pump using the heat of the underground water to create heat in your homes.

Greg: What they’ve done is turned it into a geothermal opportunity.

Dylan: But even so, Greg has said it has been pretty hard to get anyone to pay attention. Warming groundwater, maybe not the sexiest issue out there.

Greg: I went to a TV news channel who wanted to do the story, but she said, well, you don’t have any visuals, so we can’t. And well, what do I do? I mean, what are you supposed to photograph for warming groundwater? Maybe someone throwing up in a toilet? Does that do it for you?

Dylan: In 2008, Minneapolis shut down any access to Schieks Cave. They passed a law making it illegal to enter critical infrastructure, which now includes this cave. It was not Greg’s research particularly that led to the shutdown. These things travel, and once word got out, it became something of a hotspot for urban explorers. To be fair, I probably would have been one of those urban explorers if I had been in town when this was all happening.

Greg: As for urban explorationists with many fields and hobbies and so on, you know, the internet has just drastically increased the traffic in these places.

Dylan: Today the cave is off limits, hidden behind a manhole, and also politics. It blocks potential explorers. And most of the people who walk on the city’s busy streets, including myself when I go home to visit my parents, we are all oblivious to this world just 75 feet below us. But Greg Brick remains hopeful. He may have started out as a curious explorer, but he believes that his research and passion for exploring this forgotten world underneath the city, one day he hopes will bring attention to both the cave’s rich historical lore and its potential impact on science.

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

This episode was produced by Jala Everett. Our podcast is a co-production of Atlas Obscura and Stitcher Studios. The people who make our show include Doug Baldinger, Chris Naka, Kameel Stanley, Johanna Mayer, Manolo Morales, Baudelaire, Amanda McGowan, Alexa Lim, Casey Holford, and Luz Fleming. Our theme music is by Sam Tindall.