Ne Zha 2 director launched his career with this wild animated short — and a much wilder backstory

The meteoric rise of the Chinese movie Ne Zha 2 has been stunning: The sequel has broken worldwide records for an animated movie, and as of this writing, has reportedly earned more than $2 billion at the international box office, putting it at No. 5 on the all-time highest-grossing-movie list, above Star Wars: The Force […]

The meteoric rise of the Chinese movie Ne Zha 2 has been stunning: The sequel has broken worldwide records for an animated movie, and as of this writing, has reportedly earned more than $2 billion at the international box office, putting it at No. 5 on the all-time highest-grossing-movie list, above Star Wars: The Force Awakens. The film’s success has prompted an industry wave of speculation about what this might mean for the future of Chinese animation, fantasy films, and imported entertainment. But it’s worth looking back as well, specifically to the surprising animated short that began the extremely unlikely career of Ne Zha and Ne Zha 2 writer-director Yang Yu, aka Jiao Zi.

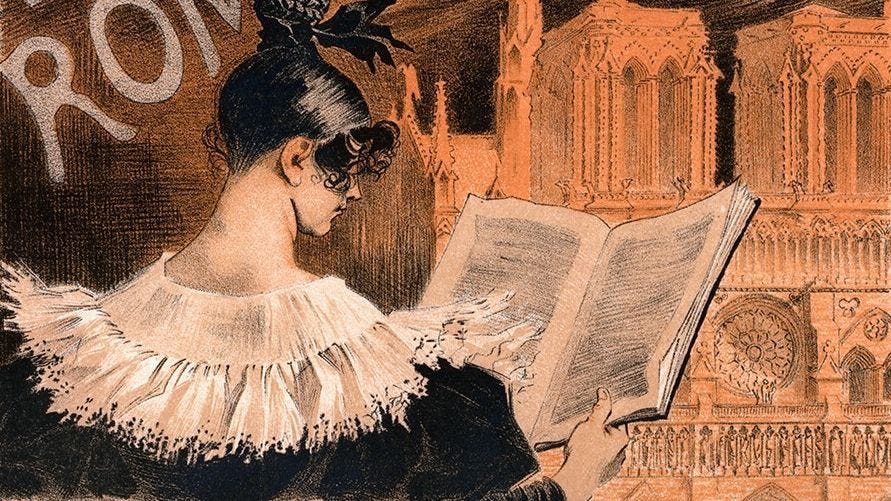

“Jiao Zi” is a pseudonym meaning “dumpling,” but it isn’t the first pseudonym the animator operated under. See Through, his 2008 debut short — available to stream free on YouTube — was made under the name “Jokelate” as a personal project. In a 2009 interview translated at Zona Europa, Jiao Zi says he went to medical school as a nod to a practical career. But after learning how to use 3D rendering software and seeing a fellow student leave to pursue creative work, he decided he wanted to pursue animation instead.

He graduated from medical school, but then went to work for a year at an ad agency that specialized in 3D graphics. With that experience under his belt, he quit to work on his own project. Living with his retired mother, he made the process of creating this short his central focus. From that 2009 interview:

My father passed away when I first started working. My mother is retired and receives 1,000 yuan in retirement benefits. She lived with me, and we spent as little as possible. I basically did not buy any clothes. My mother took care of the food by looking for special sales times at the supermarket. We were basically vegetarian, which is both economical and healthy. We lived in an apartment that my parents bought with their savings along with a bank mortgage. The monthly loan payments is more than 700 yuan, which is half of our monthly expenses. I don’t travel, because only rich people do that. I have not gone more than 40 kilometers away from my home over the past three and a half years.

He also says he didn’t have internet access during that era. “If I needed to get on the Internet, I go to a friend’s house.” Living in isolation, he taught himself how to use the software he used for See Through. “My life centered around three spots: the living room, the bedroom and the bathroom,” he said.

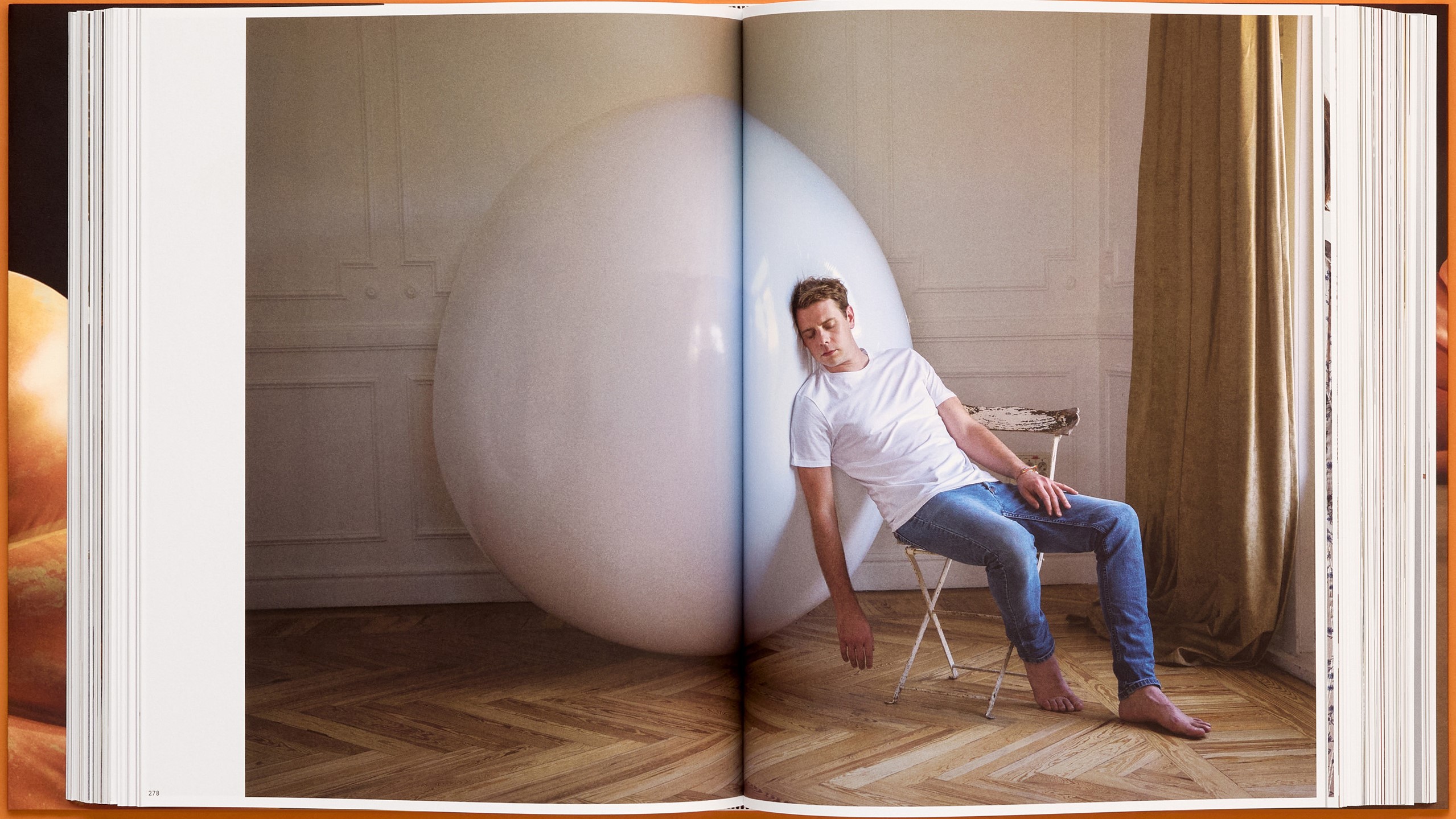

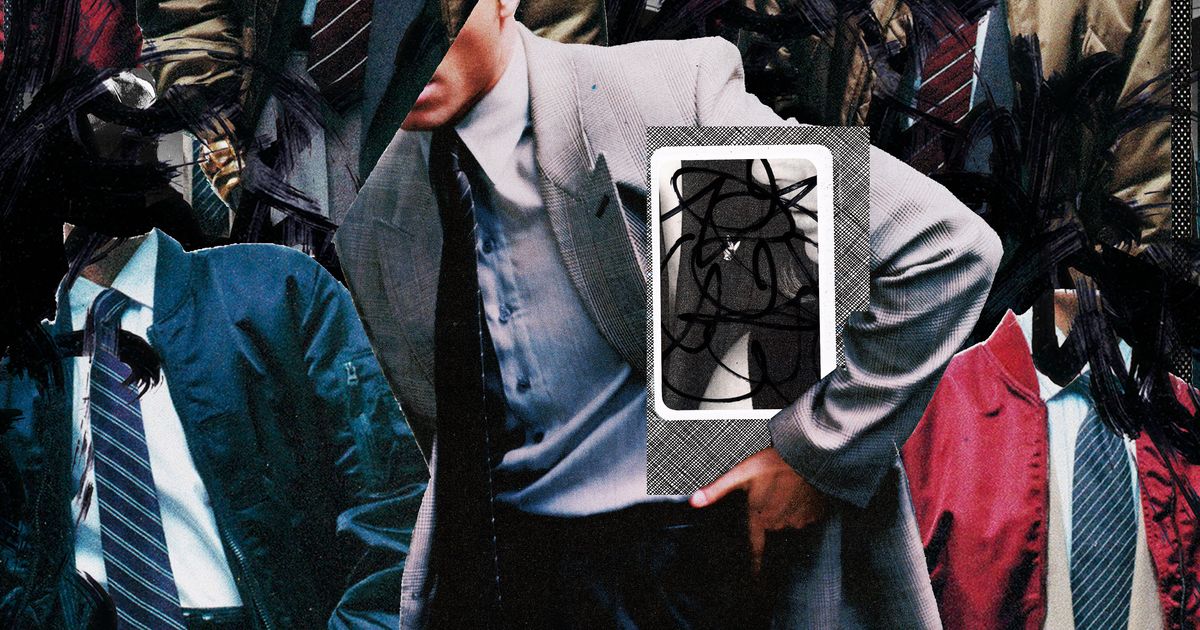

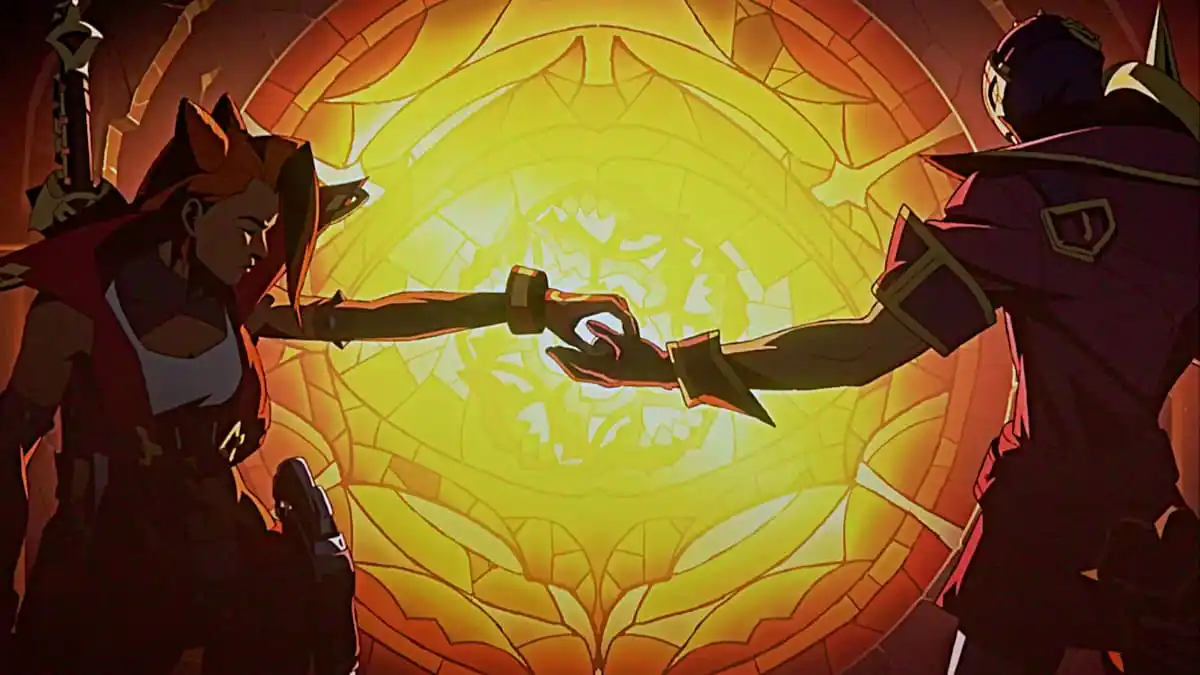

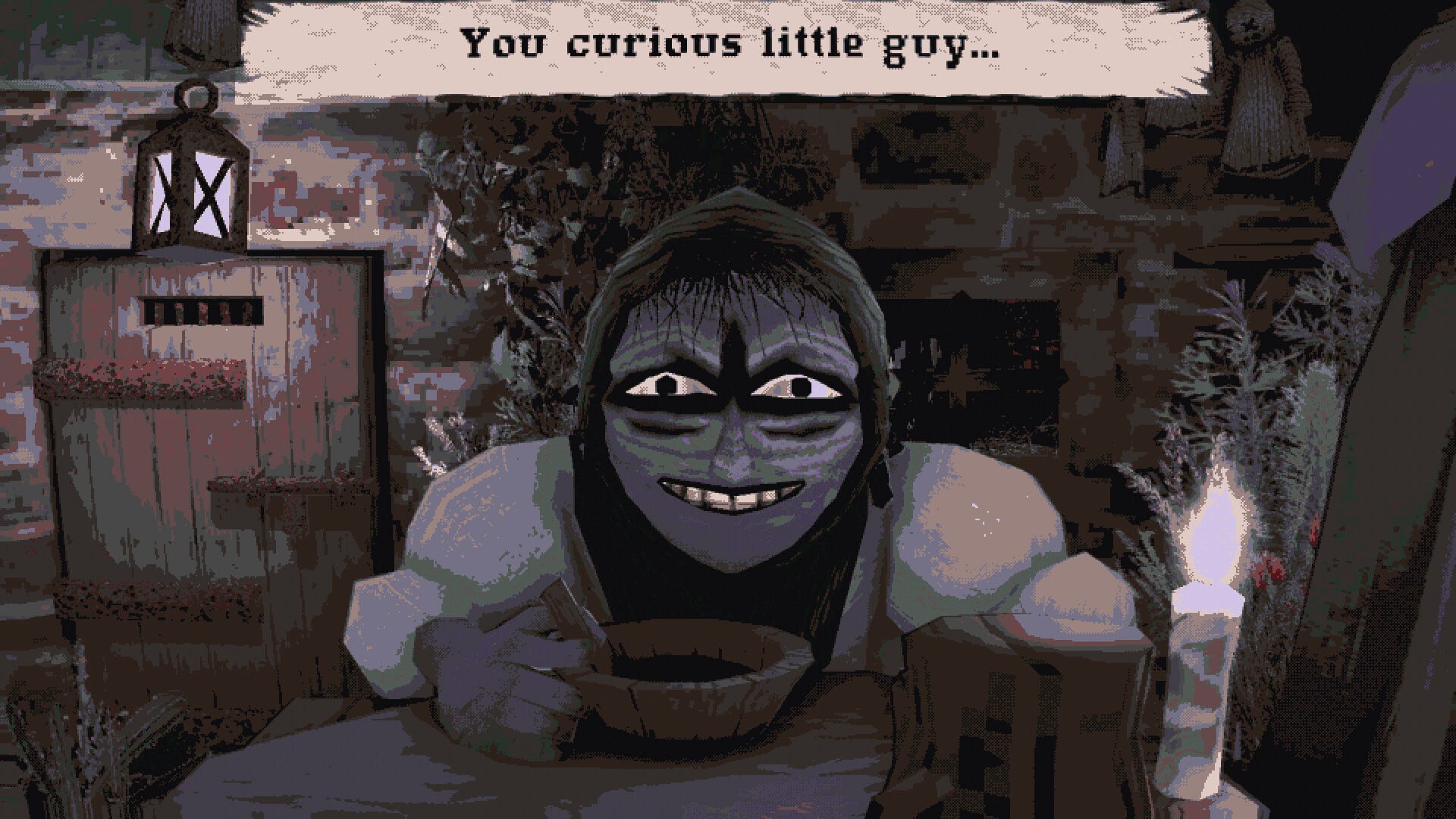

The long process of making the film explains See Through’s strange, rough cadence. It tells one continuous metaphorical story, but operates in a series of vignettes, animated in radically different styles. In black-and-white segments styled as a German expressionist drama, a pair of powerful symbolic figures treat each other collegiately while dividing the world up between them, but eventually go to war over an isolated island. (There’s a sly visual joke in the island being shaped like a bone these two jackals are tussling over.) More cartoony segments see fleets of ships and battalions of foot soldiers, stylized as decks of playing cards, into combat with each other. Eventually, two pilots from opposite sides are stranded on an island together, and learn they’re happier in isolation with each other than they were among their respective militaries.

That pointed anti-war message feels a little ironic from the writer and director of two movies that focus so heavily on lovingly animated, visually rich combats between huge powers. But the sensibility of the Ne Zha movies is intact in See Through, from the grand scale to the visual humor to the focus on bodily functions. (The sequence where one of the pilots tries to use his own nosebleed physics to kill the other one is a particular highlight.) There are early hints of Jiao Zi’s sentimentality and convictions as well — the central character of the Ne Zha movies suffers tremendous emotional losses because of other people’s wars in Ne Zha 2, and characters find over and over that their family connections mean more to them than the cosmic gods-and-monsters conflicts going on around them.

After See Through began to get him attention, Jiao Zi founded his own small animation house, Jokelate Studios, but struggled to find funding for animated projects. A 2015 partnership with Beijing-based Coloroom Pictures (Big Fish & Begonia) helped him get Ne Zha to the screen in 2019, and the sequel followed. With Ne Zha 2 making such an immense splash in the market, the company is likely to be able to ramp up production and find more investors for more epic-scale animated movies. But none of them are likely to feel as scrappy, handmade, and personal as the project the director made from his mother’s living room nearly 20 years ago.

![Everything Patrick Schwarzenegger Cooks in a Day [Exclusive]](https://cdn.apartmenttherapy.info/image/upload/f_auto,q_auto:eco,c_fill,g_auto,w_660/k/Design/2025/03-2025/k-cooking-diaries-patrick-schwarzenegger/cooking-diaries-patrick-schwarzenegger-lead)

.jpg)