The Grateful Dead’s Wall of Sound Changed Live Music Forever

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. Dylan Thuras: I work from home for the most part, and, you know, in my home office, as much as I have one, I kind of end up working all over my house. Anyway, you know, I have plants. I’ve got some souvenirs, stuff I’ve collected from trips. But in my friend Brian Anderson’s home office, he has what you could describe as a very, very large paperweight. It is a 65-pound speaker, the size of an oven, that does not work. And, actually, when I talked to Brian on Zoom, I could see this giant thing lurking in the background just behind him. Yes! So big! Oh my god! Brian Anderson: Yeah, I could, like, crawl inside of it if I wanted to. Dylan: Is it wired up? Brian: No, it’s not. I kind of, at least like right now, I kind of like the idea of just, like, preserving its integrity as just this, like, road-borne hunk of junk kind of, you know? Dylan: Yeah. Brian: It just hangs out. It’s just a little slice of audio history here. Dylan: This is a special speaker. It is very much secondhand, very well used. But the thing that makes it special is that it used to belong to the band The Grateful Dead. Brian: I won it at a 2021 Sotheby’s auction of decommissioned gear from The Grateful Dead’s Northern California warehouse. The final hour, it was me and just someone out there just going, like, tit for tat and quickly escalated. And at a certain point, I’m like, I’m locked into this now. Dylan: I’ve gone too far. Brian: I’ve gone too far, yeah. Dylan: There’s no coming back. Brian: It’s the point of no return. Dylan: Brian is a Grateful Dead superfan. And, in part, it’s because he was kind of born into it. Both his parents are serious Deadheads. Brian went to his first Grateful Dead show when he was three years old. But this is actually not why Brian wanted to own this speaker. Brian wanted this speaker because he had a hunch that this speaker was an artifact of a groundbreaking piece of technology, something called the Wall of Sound. Brian: The Wall was a singular public address or PA system that really revolutionized and, in many ways, kind of set the blueprint for the modern entertainment industry as we know it today. Dylan: From the very beginning, the Dead wanted to do something pretty radically different with their concerts. They started out in the ’60s during the acid tests in San Francisco. This was where people would get together and trip and sort of attempt to have a kind of unified mystical experience together. Even when the acid had dried up, the Dead wanted to keep this experience going. They wanted to use the music and their technology to create a kind of space where fans could transcend the everyday. They wanted to do this everywhere they went, everywhere they played. And this is where the Wall of Sound came in. This movable, 60-foot-tall, 75-ton PA system that included over 600 speakers. Brian was pretty sure that his speaker was a part of it. Brian: This thing arrives looking like something out of Indiana Jones or something, like it’s packed up in like a wooden crate. You know, I had my dad do the honors of like drilling this thing open and we open it up and I stick my head inside of it and, you know, thinking about the sound waves that were flowing out of it and the, you know, hundreds of thousands of people who received those sound waves, you know, including my parents. It has a story, right? This much bigger story about obsession and titanic human achievement. I’m Dylan Thuras and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. If I am really honest, I have never particularly liked the Grateful Dead. I’ve frankly never taken that much of an interest in them. At least I didn’t before talking to Brian Anderson, author of a new book on the Grateful Dead’s Wall of Sound, this monstrous tower of speakers. And the thing is, this wall is a lot bigger than the man. It is this story of an obsessive quest to bring crystal clear sound from the nosebleeds to the front row and back again. It is this quest that would eat up 10 years, millions of dollars, and very nearly broke up the band. This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. Dylan: Let’s start at the beginning. The Grateful Dead started in the 1960s in the Bay Area and they get involved with this legendary scene, the acid test. What was an acid test and what was it like to attend one? Brian: It really does all go back to the acid tests, which were mind-expanding, psychedelic-fueled, audiovisual happenings that went down on the West Coast from Portland to Los Angeles. And the tests were organized by the author Ken Kesey, who was enjoying the success of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, his breakout novel. So participants at these events would gain entry by paying a

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Dylan Thuras: I work from home for the most part, and, you know, in my home office, as much as I have one, I kind of end up working all over my house. Anyway, you know, I have plants. I’ve got some souvenirs, stuff I’ve collected from trips. But in my friend Brian Anderson’s home office, he has what you could describe as a very, very large paperweight. It is a 65-pound speaker, the size of an oven, that does not work. And, actually, when I talked to Brian on Zoom, I could see this giant thing lurking in the background just behind him. Yes! So big! Oh my god!

Brian Anderson: Yeah, I could, like, crawl inside of it if I wanted to.

Dylan: Is it wired up?

Brian: No, it’s not. I kind of, at least like right now, I kind of like the idea of just, like, preserving its integrity as just this, like, road-borne hunk of junk kind of, you know?

Dylan: Yeah.

Brian: It just hangs out. It’s just a little slice of audio history here.

Dylan: This is a special speaker. It is very much secondhand, very well used. But the thing that makes it special is that it used to belong to the band The Grateful Dead.

Brian: I won it at a 2021 Sotheby’s auction of decommissioned gear from The Grateful Dead’s Northern California warehouse. The final hour, it was me and just someone out there just going, like, tit for tat and quickly escalated. And at a certain point, I’m like, I’m locked into this now.

Dylan: I’ve gone too far.

Brian: I’ve gone too far, yeah.

Dylan: There’s no coming back.

Brian: It’s the point of no return.

Dylan: Brian is a Grateful Dead superfan. And, in part, it’s because he was kind of born into it. Both his parents are serious Deadheads. Brian went to his first Grateful Dead show when he was three years old. But this is actually not why Brian wanted to own this speaker. Brian wanted this speaker because he had a hunch that this speaker was an artifact of a groundbreaking piece of technology, something called the Wall of Sound.

Brian: The Wall was a singular public address or PA system that really revolutionized and, in many ways, kind of set the blueprint for the modern entertainment industry as we know it today.

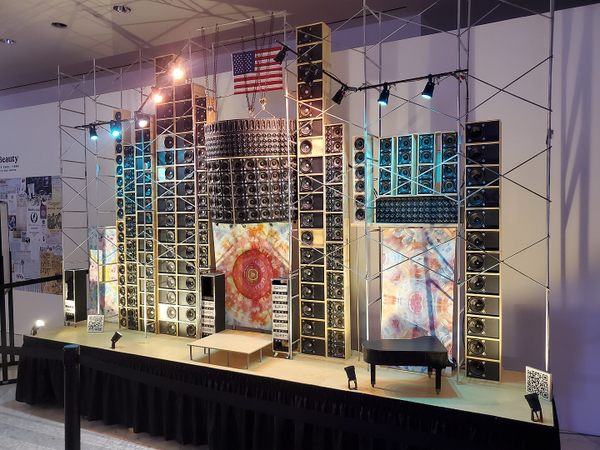

Dylan: From the very beginning, the Dead wanted to do something pretty radically different with their concerts. They started out in the ’60s during the acid tests in San Francisco. This was where people would get together and trip and sort of attempt to have a kind of unified mystical experience together. Even when the acid had dried up, the Dead wanted to keep this experience going. They wanted to use the music and their technology to create a kind of space where fans could transcend the everyday. They wanted to do this everywhere they went, everywhere they played. And this is where the Wall of Sound came in. This movable, 60-foot-tall, 75-ton PA system that included over 600 speakers. Brian was pretty sure that his speaker was a part of it.

Brian: This thing arrives looking like something out of Indiana Jones or something, like it’s packed up in like a wooden crate. You know, I had my dad do the honors of like drilling this thing open and we open it up and I stick my head inside of it and, you know, thinking about the sound waves that were flowing out of it and the, you know, hundreds of thousands of people who received those sound waves, you know, including my parents. It has a story, right? This much bigger story about obsession and titanic human achievement.

I’m Dylan Thuras and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. If I am really honest, I have never particularly liked the Grateful Dead. I’ve frankly never taken that much of an interest in them. At least I didn’t before talking to Brian Anderson, author of a new book on the Grateful Dead’s Wall of Sound, this monstrous tower of speakers. And the thing is, this wall is a lot bigger than the man. It is this story of an obsessive quest to bring crystal clear sound from the nosebleeds to the front row and back again. It is this quest that would eat up 10 years, millions of dollars, and very nearly broke up the band.

This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Dylan: Let’s start at the beginning. The Grateful Dead started in the 1960s in the Bay Area and they get involved with this legendary scene, the acid test. What was an acid test and what was it like to attend one?

Brian: It really does all go back to the acid tests, which were mind-expanding, psychedelic-fueled, audiovisual happenings that went down on the West Coast from Portland to Los Angeles. And the tests were organized by the author Ken Kesey, who was enjoying the success of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, his breakout novel. So participants at these events would gain entry by paying a dollar, drinking some LSD-spiked fruit punch, and then tripping out with fellow travelers. And they sort of, you know, quote-unquote, passed the test if they made it through the end of the night. And the idea was to summon a hive mind, a gestalt, if you will, through psychedelic drugs and sound and light and improvised music. And the Dead were really the de facto acid test house band. Kesey later said of one of these early acid tests, when the Dead were playing, that sound was washing around the hall. And nobody had ever heard anything like this, where they were part of the ambience of the sound.

Dylan: This whole thing about going into the hive mind, I mean, was there something about the kind of music they were playing that was meant to go along with all of this experience? Was there something about what they were doing that, like, helped usher people into that hive mind?

Brian: Yeah, I think the music was a vehicle or, like, a catalyst to get there, to sort of travel together. And one of the principal characters in the book is the late Augustus Owsley Stanley III. He was an eccentric Kentucky-born amateur audiophile, chemist, kind of jack-of-all-trades, whose hairy chest earned him the nickname Bear. So between 1965 and 1967, Bear manufactured loads of highly potent LSD. So I’m talking millions of hits of acid. And the journalist Jay Stevens later wrote that without Bear, the acid test probably would never have taken place for the simple reason that LSD was too difficult to obtain. The large quantities of money that Bear was making from making LSD allowed him to bankroll the band. So Bear was their patron, and he was kidding them out with top flight gear at a very early stage of their career. And Bear was partially deaf in one ear, and he claimed to be able to see sound. And Bear saw, you know, putting saw in quotes here, he saw the sound emanating from these speakers while he sat around high on his own supply of acid, watching the band rehearse. And as Bear later recalled, the sound was completely three-dimensional. And ever since then, he said, that’s how I viewed sound, having real dimensionality that changes as you move around in a space.

Dylan: Yeah, which is right on.

Brian: Which is right on, yeah. And the Dead and the Wall were really a vehicle for Bear to conjure the physical manifestation of that feeling as the band and the audience sort of like traveled together at shows.

Dylan: Bear started to pull in serious audiophiles, engineers, and inventors into the Dead’s orbit. And they started this manufacturing company in the Bay Area to make instruments and other sorts of audio equipment. And that company still exists today. And the thing they wanted to do was make every link in the audio chain absolutely perfect. It became an obsession for Bear and for the band.

Brian: I think it goes back to the acid tests and how the barrier between the performers and the crowd sort of dissolved in those sorts of spaces. As the Dead scaled up, they wanted to sort of, you know, preserve that model. They wanted to project sound to someone sitting in the furthest reaches of a hall, like way in the nosebleeds. They wanted that person to have the same exact quality of experience as someone who was like right up front, you know, hanging like, you know, right on the stage, just like getting their minds blown. So that’s who they were playing for. And I think that obsession, like, it was kind of infectious. Like, they all just kind of started feeding on it, you know.

Dylan: It is worth mentioning just how bad live concert sound was in the 1960s. Back then, the sound systems at most venues were not designed for electric instruments at all. So the Dead’s team, led by Bear, had to do a lot of innovating and inventing as they went along. They created this whole system of monitors that sat behind the band so that the musicians could actually hear what the audience was hearing. And then, in order for that to work, they had to invent a bunch of feedback-canceling microphones. It was a surprisingly technically complex project.

Brian: The Wall of Sound, as we know, it was the culmination of essentially like a 10-year project. So to give a quick sense of really just how quickly their sound system manifest was scaling up in these crucial on-ramp years into the full Wall of Sound. In 1965, when it sort of all began, the Dead’s rig weighed 800 pounds and was transported in drummer Bill Kreutzman’s station wagon.

Dylan: You can picture him with like dollies or whatever, just like wheeling in these speakers. Takes a few people, but like a thing you can do as like a couple of guys.

Brian: Exactly. Exactly. Yes. But then, two years later, the Dead’s rig came in at 6,000 pounds. And by that point, it was being schlepped around in a big metro van. By 1970, their rig weighed 10,000 pounds and was being moved around in their own 18-foot box truck. By 1973, when the system had clearly taken the shape of a prototype Wall of Sound, and when the band played truly gigantic shows, the rig at that point weighed 30,000 pounds.

Dylan: Oh my, that’s a big jump.

Brian: Yeah, they really leveled it up. And then a year later, by 1974, sort of like the peak of the Wall of Sound proper as we know it, the Dead’s system, including all of the speaker cabinets like my artifact, the amplifiers, the custom staging, and the scaffolding, etc., clocked in at 75 tons. And by that point, the rig was being transported in a small fleet of, I think, three or four 40-foot trucks. They would send an advanced team to, you know, go get a lay of the land. You know, some of the technicians on the Dead crew even had, you know, one-tenth scale models of the Wall of Sound. They would, you know, get basically these little like Lego sets and just kind of work it out before the show started. So no other band was approaching anything even remotely on this scale.

Dylan: Okay, so 1974, we are at the kind of height of the Wall of Sound. The Grateful Dead is playing to gigantic shows.

Brian: Yeah.

Dylan: Put us in some of those shows. What was it like to actually see and experience the Wall of Sound?

Brian: If you look at photos of the Wall of Sound, in the center of the rig is this sort of like, Death Star looking suspended cluster of hundreds of vocal speakers. And it’s curved, it’s not flat, so that it could throw or like sweep the sound across the audience so that no matter where you were seated or standing, you kind of got that, you got that full effect. And that’s, again, a direct line back to the acid test where no boundary existed between the band and the crowd. Certainly in terms of sheer volume, the onstage noise levels with the Wall of Sound were regularly clocked with a decibel meter at 120 decibels, you know, that’s about as loud as a jet engine at close range.

Dylan: Yeah.

Brian: It’s very loud, enough to do permanent hearing damage. And yet, the sound that it reproduced was so crystalline and so clear that you could hold a conversation with someone, you know, and the sound was so inoffensive that you would hardly know that it was, you know, pushing however many dBs, you know. So, it’s amazing. The late, great Steve Silberman, a devout Deadhead and acclaimed science writer, he said that the Wall of Sound was a concrete manifestation of the idea that the band and the crowd were the same. It was cosmic democracy, is what he called it. I just love that.

Dylan: So what, what happens to the Wall? They’ve reached like this pinnacle, a 10-year journey. What happens?

Brian: The Dead only performed 40 shows with the wall of sound in 1974, which is interesting because these shows ... hold such an outsized presence in dead lore. So by the end of 1974, everything was growing out of control. They referred to the whole operation as the Ouroboros, you know, the snake eating its tail. The—just the financial costs alone were clearly untenable at this point. You know, the costs of the equipment alone came in at around $350,000 back then, which comes out to around $2.3 million today.

Dylan: Yeah. Wow.

Brian: Their monthly overhead was $100,000. So it all just, it built to a head where there was a fateful meeting in the summer of 1974 where they’re like, we got to take a break.

Dylan: It’s grown too big. The monster has—

Brian: It’s grown. Yes. It’s grown way too big.

Dylan: It’s out of control. Yeah.

Brian: And that was it. They literally pulled the plug.

Dylan: Do you think part of it, though, is that they just achieved the thing? Like, in a certain way, they actually, like, they reached the maximum, like, there wasn’t maybe somewhere else to go, or they didn’t feel like there was somewhere else to go. And so once you’ve achieved the impossible, maybe it’s kind of like, oh, we did it, guys. Like, now we can just chill out a little bit and, like, go back to playing some more modest stuff.

Brian: Right. Yeah, I think they realized that they didn’t need to carry all this stuff around with them anymore. And that’s in large part due to the innovations that they achieved through working on the Wall of Sound. And they’re pushing the state of the art. When they came back after their hiatus, when they came back in 1976, they could use, like, much more compact, streamlined, like, rented sound systems that sounded just as good, if not even better than The Wall of Sound. But again, that’s sort of, you know, in no small part thanks to the work that they did on the Wall of Sound.

Dylan: So you’ve done a good job convincing me that there’s, like, a lot here to be interested in.

Brian: Yeah.

Dylan: That it is a much more radical, technical, weird kind of story than I think I’ve been holding in my head. What would you say is important about the Dead’s role in music, in the creation of kind of spectacle or sound?

Brian: I think although the Wall of Sound didn’t last too long, its impact on the entertainment industry, and really the Grateful Dead’s impact on the entertainment industry, is undeniable. And I think musicians, performers, fans, consumers, Deadheads, and people who don’t even really like the band all occupy a zone that was opened up through The Wall of Sound.

Dylan: I think what I’m hearing you say is that any time someone is, like, at a Skrillex concert and the entire 3,000 people feel like, whoa, they basically have to thank the Grateful Dead for this, at least in some part.

Brian: If you’re at the Skrillex show and you’re feeling the sound as much as you’re hearing the sound, right, and no matter where you are in the audience, right, like, you’re getting like that full, like, sensory effect, that really all goes back to the Dead. And as I like to say, it’s a Dead world. We’re just living in it.

Dylan: Brian Anderson is the author of Loud and Clear: The Grateful Dead’s Wall of Sound and the Quest for Audio Perfection. There is just a ton of interesting stuff in there. Whether you like the Dead or not, I found this just really fascinating. Check it out. I am off to listen to some sweet, crispy riffs.

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Our podcast is a co-production of Atlas Obscura and Stitcher Studios. This episode was produced by Amanda McGowan. The people who make our show include Doug Baldinger, Chris Naka, Kameel Stanley, Johanna Mayer, Manolo Morales, Amanda McGowan, Alexa Lim, Casey Holford, and Luz Fleming. Our theme music is by Sam Tindall.