The Lingering Mystery of the 'Lost Colony' of Roanoke

In late summer of 1937, a man named Louis E. Hammond emerged from the tupelo gums and cypresses of the North Carolina wilderness with a 21-pound piece of quartz, onto which had been inscribed a nearly indecipherable, enigmatic message. The Californian had been traveling through on vacation when he’d stopped at Edenton, on the northern shore of Albemarle Sound, near the mouth of the Chowan River. It was in the forest along the Chowan’s banks, he would later explain, that he’d found the strange rock, which he took to Emory University that fall. A group of researchers at Emory, including historian Haywood Pearce, Jr., set to deciphering it, and soon realized that this stone might hold a clue to one of the great unsolved mysteries of American history. More than three centuries earlier, Sir Walter Raleigh had attempted to found a colony off the North Carolina coast, in the swamplands cradled by the Outer Banks. A colony under the command of Ralph Lane was founded on Roanoke Island in 1585, but they immediately ran into trouble, lacking supplies and clashing with the largely Algonquin-speaking Indigenous community. When a resupply ship failed to arrive on time, the colonists fled back to England; the ship, arriving some time later to a deserted colony, left behind a garrison of 15 soldiers to defend the territory, and then returned home. Those men were never heard from again, but Raleigh, undeterred, launched a second attempt, this time under the command of John White. Landing on Roanoke in 1587, White founded the “Cittie of Raleigh,” which would hopefully secure Raleigh’s colonial claim in the New World. White returned to England shortly thereafter, leaving behind just over a hundred colonists (the exact number varies, but they included White’s pregnant daughter, Eleanor White Dare), promising to come back with supplies in a year. But his return was thwarted by the outbreak of the Anglo-Spanish War, when every seaworthy British vessel was mustered into a massive fleet to face the Spanish Armada. White and Raleigh ultimately could not get a ship back to North Carolina until 1590. When White finally arrived, he found the colony deserted. The only sign left behind was one word carved into a wooden palisade: CROATOAN. White assumed this meant the colonists had moved to nearby Croatoan Island, and set out to find them there, but rough weather prohibited a landing, and after the ship lost its anchor, White was left with no choice but to return to England. The fate of the Lost Colony, as it came to be known, had been a mystery ever since. But now, a stone scratched with an enigmatic message, found some 60 miles inland from Roanoke, appeared to have some answers. We normally view history as a stable, linear narrative: One thing follows another, cause leads to effect, and the decisions of the past pile up all around us, influencing our choices in the present and the possibilities of the future. But unsolved mysteries disturb this order. With no sense of what happened, we’re at a loss to understand how these mysterious events may (or may not) have determined the events that followed. The mystery exists outside of our cause-and-effect narratives, unable to explain anything that might have followed it. But it doesn’t disappear entirely: Like a ghost, it lingers, still somehow present but persistently ambiguous. The story of the Lost Colony lingers, precisely because it is a mystery, and, in all likelihood, will always be one. Everything about it augurs tragedy, but what kind of tragedy remains undefined. Even worse still, the absence here represents failure: a failure of a colonial enterprise, a failure of Europeans’ supposed technological and moral superiority over Indigenous people, a failure of the indomitable will of humanity to survive and thrive. Across a span of centuries, the remains of an inexplicable defeat leer at us, calling out from the realm of the unknown. Most eerie of all, perhaps, is that one word—CROATOAN. The fact that historians overwhelmingly agree that it was likely a note left behind for rescuers, indicating where the colony had departed to, has not stopped writers and filmmakers from conjuring ghost stories and hauntings based on that solitary, enigmatic word—from Harlan Ellison and Stephen King to American Horror Story: Roanoke (and the far less beloved Syfy original movie Wraiths of Roanoke). Across a span of centuries, the remains of an inexplicable defeat leer at us, calling out from the realm of the unknown. But it’s not just fiction writers; the Lost Colony’s unresolved nature has long made it a prime target for the imaginings of North America’s past. Writers have used fiction and history to hypothesize the fate of the Lost Colony—and their various attempts to explain what happened invariably reveal a great deal about their own attitudes toward the world at the time. Almost from the beginning, writers tried to rationalize events in a way that made them feel better about

In late summer of 1937, a man named Louis E. Hammond emerged from the tupelo gums and cypresses of the North Carolina wilderness with a 21-pound piece of quartz, onto which had been inscribed a nearly indecipherable, enigmatic message. The Californian had been traveling through on vacation when he’d stopped at Edenton, on the northern shore of Albemarle Sound, near the mouth of the Chowan River. It was in the forest along the Chowan’s banks, he would later explain, that he’d found the strange rock, which he took to Emory University that fall. A group of researchers at Emory, including historian Haywood Pearce, Jr., set to deciphering it, and soon realized that this stone might hold a clue to one of the great unsolved mysteries of American history.

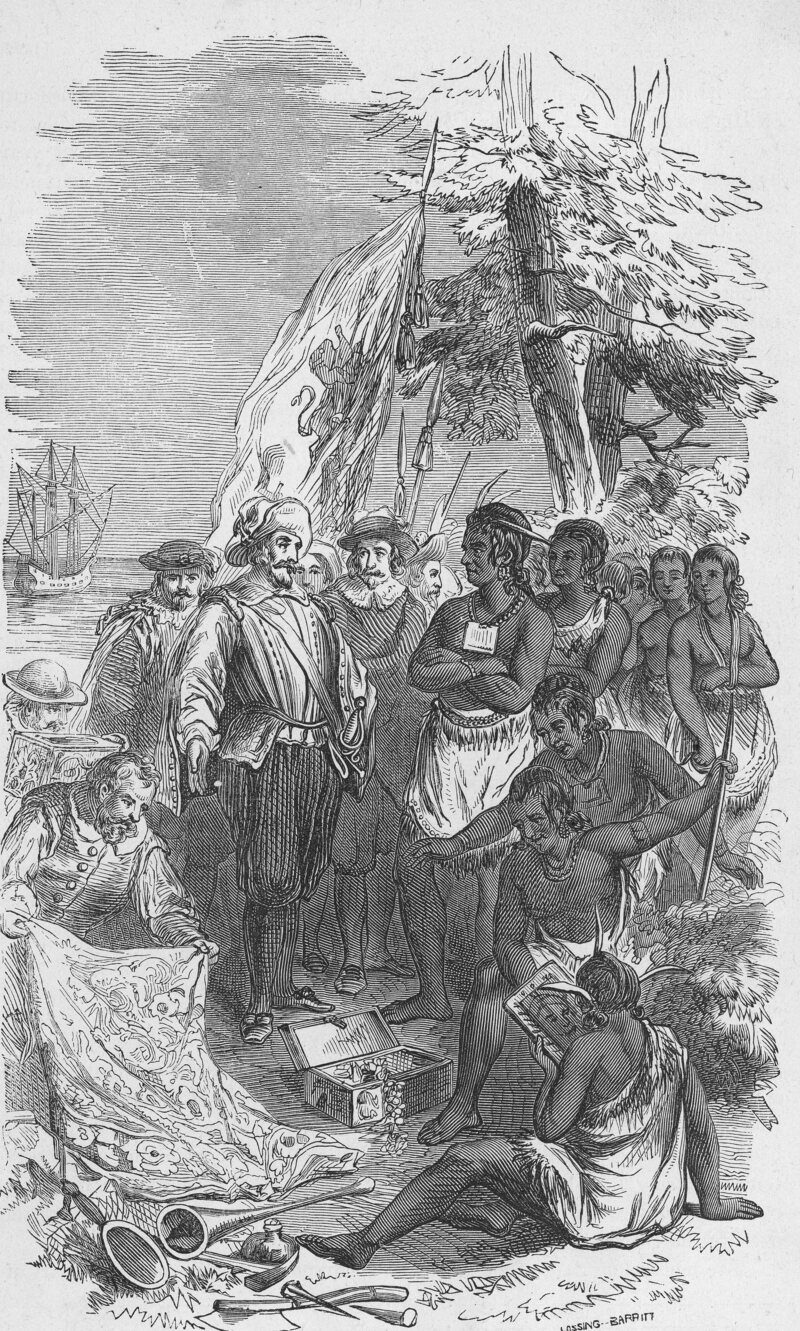

More than three centuries earlier, Sir Walter Raleigh had attempted to found a colony off the North Carolina coast, in the swamplands cradled by the Outer Banks. A colony under the command of Ralph Lane was founded on Roanoke Island in 1585, but they immediately ran into trouble, lacking supplies and clashing with the largely Algonquin-speaking Indigenous community. When a resupply ship failed to arrive on time, the colonists fled back to England; the ship, arriving some time later to a deserted colony, left behind a garrison of 15 soldiers to defend the territory, and then returned home.

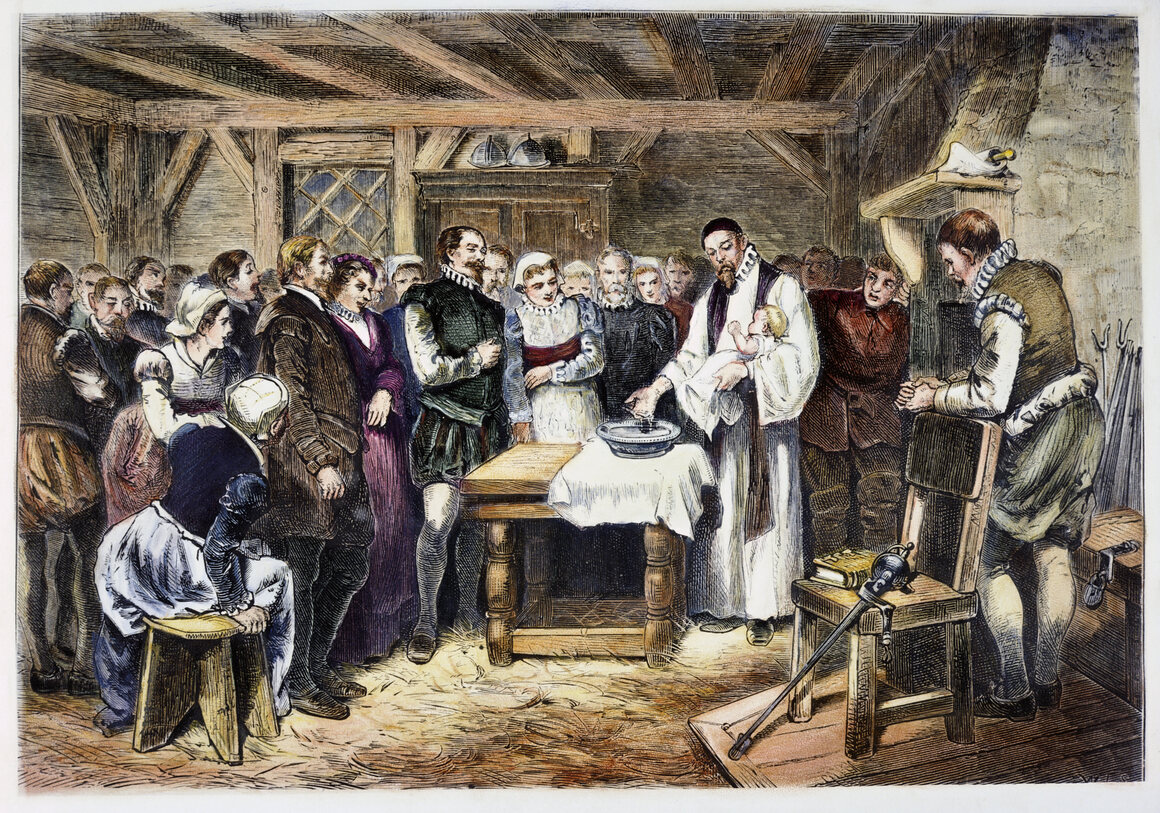

Those men were never heard from again, but Raleigh, undeterred, launched a second attempt, this time under the command of John White. Landing on Roanoke in 1587, White founded the “Cittie of Raleigh,” which would hopefully secure Raleigh’s colonial claim in the New World. White returned to England shortly thereafter, leaving behind just over a hundred colonists (the exact number varies, but they included White’s pregnant daughter, Eleanor White Dare), promising to come back with supplies in a year. But his return was thwarted by the outbreak of the Anglo-Spanish War, when every seaworthy British vessel was mustered into a massive fleet to face the Spanish Armada. White and Raleigh ultimately could not get a ship back to North Carolina until 1590.

When White finally arrived, he found the colony deserted. The only sign left behind was one word carved into a wooden palisade: CROATOAN.

White assumed this meant the colonists had moved to nearby Croatoan Island, and set out to find them there, but rough weather prohibited a landing, and after the ship lost its anchor, White was left with no choice but to return to England. The fate of the Lost Colony, as it came to be known, had been a mystery ever since.

But now, a stone scratched with an enigmatic message, found some 60 miles inland from Roanoke, appeared to have some answers.

We normally view history as a stable, linear narrative: One thing follows another, cause leads to effect, and the decisions of the past pile up all around us, influencing our choices in the present and the possibilities of the future. But unsolved mysteries disturb this order. With no sense of what happened, we’re at a loss to understand how these mysterious events may (or may not) have determined the events that followed. The mystery exists outside of our cause-and-effect narratives, unable to explain anything that might have followed it. But it doesn’t disappear entirely: Like a ghost, it lingers, still somehow present but persistently ambiguous.

The story of the Lost Colony lingers, precisely because it is a mystery, and, in all likelihood, will always be one. Everything about it augurs tragedy, but what kind of tragedy remains undefined. Even worse still, the absence here represents failure: a failure of a colonial enterprise, a failure of Europeans’ supposed technological and moral superiority over Indigenous people, a failure of the indomitable will of humanity to survive and thrive. Across a span of centuries, the remains of an inexplicable defeat leer at us, calling out from the realm of the unknown.

Most eerie of all, perhaps, is that one word—CROATOAN. The fact that historians overwhelmingly agree that it was likely a note left behind for rescuers, indicating where the colony had departed to, has not stopped writers and filmmakers from conjuring ghost stories and hauntings based on that solitary, enigmatic word—from Harlan Ellison and Stephen King to American Horror Story: Roanoke (and the far less beloved Syfy original movie Wraiths of Roanoke).

But it’s not just fiction writers; the Lost Colony’s unresolved nature has long made it a prime target for the imaginings of North America’s past. Writers have used fiction and history to hypothesize the fate of the Lost Colony—and their various attempts to explain what happened invariably reveal a great deal about their own attitudes toward the world at the time. Almost from the beginning, writers tried to rationalize events in a way that made them feel better about themselves. John Marston and George Chapman’s 1605 play, Eastward Hoe, features a character who claims that the remnants of the Lost Colony ended up intermarrying with the Algonquin population, who were “so in love with ’hem, that all treasure they have they lay at their feet.”

A hundred years later, however, the surveyor and naturalist John Lawson (who’d himself explored the Carolinas) was writing of the “Treachery of the Natives,” and how we “may reasonably suppose that the English were forced to cohabit with them...and that in the process of Time, they conform’d themselves to the Manners of their Indian Relations. And thus we see how apt Humane Nature is to degenerate.” Both versions hypothesize intermarriage as the ultimate answer to the mystery, but with widely divergent interpretations of such an outcome: Either the white settlers, with their overwhelming beauty and purity, so over-awed the Algonquin that this race mingling must be seen as a victory for Europeans, or they did so only under threat, their pure white blood being corrupted by “savages.”

While British authors in the 17th and 18th centuries had their ideas about the Lost Colony, it wasn’t until George Bancroft’s 1834 History of the United States that the myth and importance of Roanoke was fully established for the United States itself. Bancroft’s history of the country begins not in 1776, but with its earliest colonial past, dwelling on these initial attempts of the Europeans to establish a foothold here. Bancroft was the first to call attention specifically to Eleanor White Dare’s daughter, Virginia, and the importance of the child’s place as “the first offspring of English parents on the soil of the United States.” Not “the New World” or “North America,” but “the soil of the United States,” a subtle but important turn of phrase that hints at both the nation to come and that new country’s innate connection to Europe.

Bancroft wrote his history during Andrew Jackson’s presidency, when repeated banking crises and a slew of domestic upheavals—including an influx of non-British, Catholic immigrants, uprisings from enslaved Americans (including Nat Turner’s rebellion), and Jackson’s weakening of the federal government’s power—all seemed, at times, like they might swamp the American project altogether. Seizing on the country’s earliest colonial past, and specifically the story of Virginia Dare, was an attempt to ground the nation in a transcendental story of resolve and divine favor. For Bancroft, whatever may have happened to her (he didn’t speculate) was less important than the very fact of her existence, as the promise of what was to come. As he makes clear in his introduction, he believed that the early colonial period “contains the germ of our institutions” and specifically that the “maturity of the nation is but a continuation of its youth.” Additionally, he argues that “the fortunes of a nation are not under the control of blind destiny,” but follow “a favoring Providence.”

He was not just chronicling history; as historian Robert H. Canary has pointed out, Bancroft was writing a narrative premised on the belief that “history was the progressive unfolding of the divine will: the significant events in the past were those which pointed to the future, and his object was to construct a narrative action leading to the present.” It worked; Bancroft’s narrative of American history, born of early colonial struggle that revealed both the innate heroism and morality of European settlers and their divine mission, influenced much of 19th- and 20th-century American historiography—as well as how people came to make sense of the Lost Colony. In Cornelia L. Tuthill’s fictional story “Virginia Dare; Or, the Colony of Roanoke,” published in 1840, Virginia Dare converts the Indigenous populations she encounters to Christianity, becoming something of a folk saint, “remembered among the tribe—who preserved the history of her eventful life, as the ‘White Angel of Mercy.’”

As Robert D. Arner would explain in his 1985 analysis of the various Lost Colony narratives, Tuthill “stumbled intuitively upon the real reason for telling the tale in the first place—our profound inability to believe that over one hundred civilized, Christianized Englishmen could possibly have been wiped out by illiterate pagans.” The Lost Colony has always threatened to be a story not just of individual tragedy, but of the peril and folly of colonialism altogether. By turning Virginia Dare into a mythical figure, what Arner identifies as both an “American Artemis, the virgin huntress Diana” as well as a hybrid blend of “Protestant Madonna and Virgin,” the story of Roanoke is less tragedy than divine prophecy of the success of colonialism and the power of its martyrs.

The history of the history of the Lost Colony becomes, in Arner’s words, “the process by which the mind transforms unacceptable facts into at least minimally acceptable fictions,” a process that can happen only because there is an absence in the historical record, an absolute emptiness of known fact that we can plug up with longing and self-soothing myth. It’s why, for example, the story of the Lost Colony became a powerful narrative in the Reconstruction South, where defeated white segregationists clung to another story of white people “unjustly” defeated by non-white forces.

By the dawn of the 20th century, when the country was once again adjusting to large waves of non-white, non-Protestant immigrants, racists and segregationists turned to Virginia Dare and tried to console themselves with fictive explanations of what happened. The Reverend Joseph Blount Cheshire, at an anniversary address given at Roanoke in 1910, proclaimed that the Lost Colony had not assimilated, nor were there descendants to be sought “in the mongrel remnants, part Indian, part white, and part negro, of a decaying tribe of American savages.” Rather, he argued, they suffered “a nobler fate”: martyrdom, leaving behind only “their spiritual descendants and kindred” in “worthy and patriotic son and daughter of Carolina, Virginia, and the United States.” This racist celebration of Dare has persisted to this day. One of the more prominent white nationalist websites is named VDARE, founded in 1999, and bigots seem to turn to her story whenever they feel threatened by social change. Which is the nice thing about mysteries: They can be eerie because they remain inexplicable, but they can also be soothing because you can dream up whatever explanation you need.

Louis Hammond’s discovery in 1937 offered an end to all of this—a solution, finally, to what had happened to the Lost Colony, and a historical record that would either affirm or refute all of our metaphysical imaginings. The Dare Stone (as it came to be called) was a piece of quartz, its exterior weathered but its core still bright white, such that cutting into it created a durable and visible script. On one side was a cross, surrounded by the words

Ananias Dare and Virginia Went Hence Unto Heaven 1591

Any Englishman show John White Governor Virginia

On the other face, a longer message signed “EWD” appeared to be from Eleanor Dare herself. It was addressed to her father, and explained how, as soon as he left, misery and war befell the colony; a misunderstanding of some kind seemed to have terrified the local Indigenous population, who returned apparently believing the colonists were “angry spirits,” and slaughtered all but a few. Among the dead were Eleanor’s husband, Ananias, and her daughter, Virginia. They were buried, the stone explained, four miles east of the river, on a small hill, their graves marked with stones.

The Dare Stone offered both a series of answers, and yet posed more questions. What had happened to Eleanor and the remaining survivors after she’d carved this note? And where were the other stones, that supposedly marked the graves of the dead?

Hammond wanted Emory University to buy the stone from him, but the university declined to purchase it; instead, one of their professors who’d been tasked to analyze it, historian Haywood Pearce, Jr., bought it along with his father, who was president of nearby Brenau College. Pearce, Jr., presented his findings in The Journal of Southern History in 1938, detailing the forensic evidence that suggested the stone was genuine and what its story might mean for historians attempting to understand the Lost Colony. Additionally, both Pearces began making regular trips to Edenton to scour the nearby forest for more clues, and in February 1939 they announced a reward of $500 (over $11,000 in 2025) to anyone who could turn up another stone.

For locals, amateur historians, and treasure-seekers alike, the discovery of the stone, and the promise of others, changed the landscape around the Carolina wetlands. Suddenly every wilderness space was resonate, every inert rock or bit of landscape could—perhaps!—hold a clue, a piece of the story. Pleasure-seekers and treasure-hunters fanned out across the forests and swamps. If the story of the Lost Colony created a strange absence in the historical record, the promise of more stones made the North Carolina landscape come alive with a renewed vitality.

The Pearces would not have to wait long; that June, a man named Bill Eberhardt appeared, claiming to have found a second stone. This stone was different: The script and spelling didn’t match the first Dare Stone, and its location, in Greenville County, South Carolina, was far from where anyone had supposed the survivors might have traveled to. But Pearce took it as genuine, and soon Eberhardt appeared with more stones, ultimately more than three dozen. Like a serialized drama, Eberhardt’s stones doled out important plot points one by one, telling a story of how the colonists had migrated farther south, eventually dying out in the wilds of Georgia.

The mystery of this new group of stones was less about what had happened to the Lost Colony, and more about how a respectable historian like Pearce was taken in by such an obvious con. Eberhardt, it would later be revealed, had a long history of counterfeiting Native American relics for sale, and his supposed Dare Stones were quickly unveiled to be patent—and not very convincing—fakes. When Pearce sent the Saturday Evening Post a feature about the stones, the magazine hired journalist Boyden Sparkes to fact-check the piece and look into the stones’ provenance; based on what he found, the Post ended up hiring Sparkes to write a very different piece altogether, disclaiming the entire lot of rocks (even Hammond’s original find) as forgeries.

Currently, the entire collection is housed at Brenau College in Gainesville, Georgia, where the stones are still accessible to researchers, even though they clearly identify the Eberhardt stones as fakes and cast doubt on Hammond’s (their website notes that “there is no conclusive scientific evidence that the chiseled text is authentic and not an elaborate forgery”). But there are some who believe that the original Dare Stone may be legitimate: The language aligns with Elizabethan English (in a way Eberhardt’s patently did not), and its narrative matches what little we now do know about the colony, including information that may not have been available to scholars in 1938, let alone an amateur forger (indeed, most attempts to discredit rely mainly on Hammond’s own motivations rather than the properties of the stone itself). And so it has become a mystery unto itself. Rather than resolve the mystery of the Lost Colony, the original Dare Stone—like that eerily carved word CROATOAN—has only deepened it, and at this point your belief of its provenance, perhaps, says more about you than it does about the stone or the missing Roanoke colonists.

Which is to say, as we peer deeper into history, sometimes in lieu of clarity what we find is even more ambiguity. Often, of course, the work of history and archaeology produce new and startling answers that help further fill in gaps in the historical record. But every so often, attempts to solve mysteries only beget further mysteries.