Microsoft touts generative AI model for recreating video game visuals and controller inputs

Microsoft debuted Muse, a generative AI model that can be trained to output video game visuals and predict controller inputs. The company describes the technology as the future of gameplay ideation, not as something to be used in place of human creativity during game development. Microsoft published its Muse findings in science journal Nature, and […]

Microsoft debuted Muse, a generative AI model that can be trained to output video game visuals and predict controller inputs. The company describes the technology as the future of gameplay ideation, not as something to be used in place of human creativity during game development.

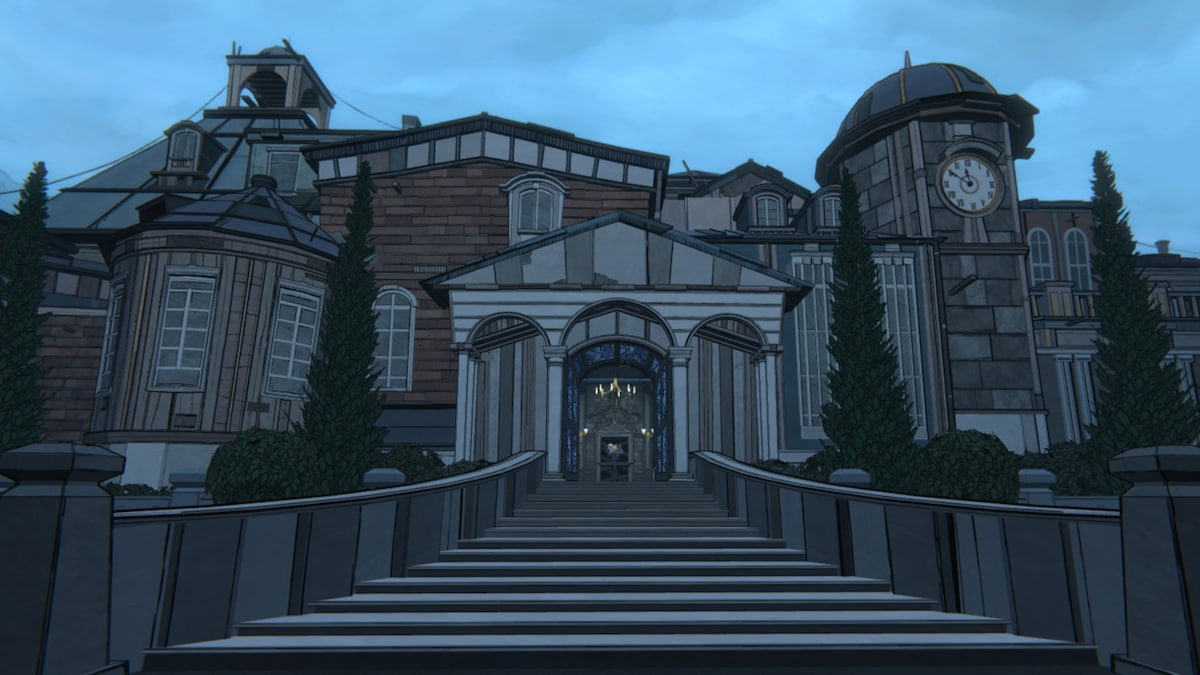

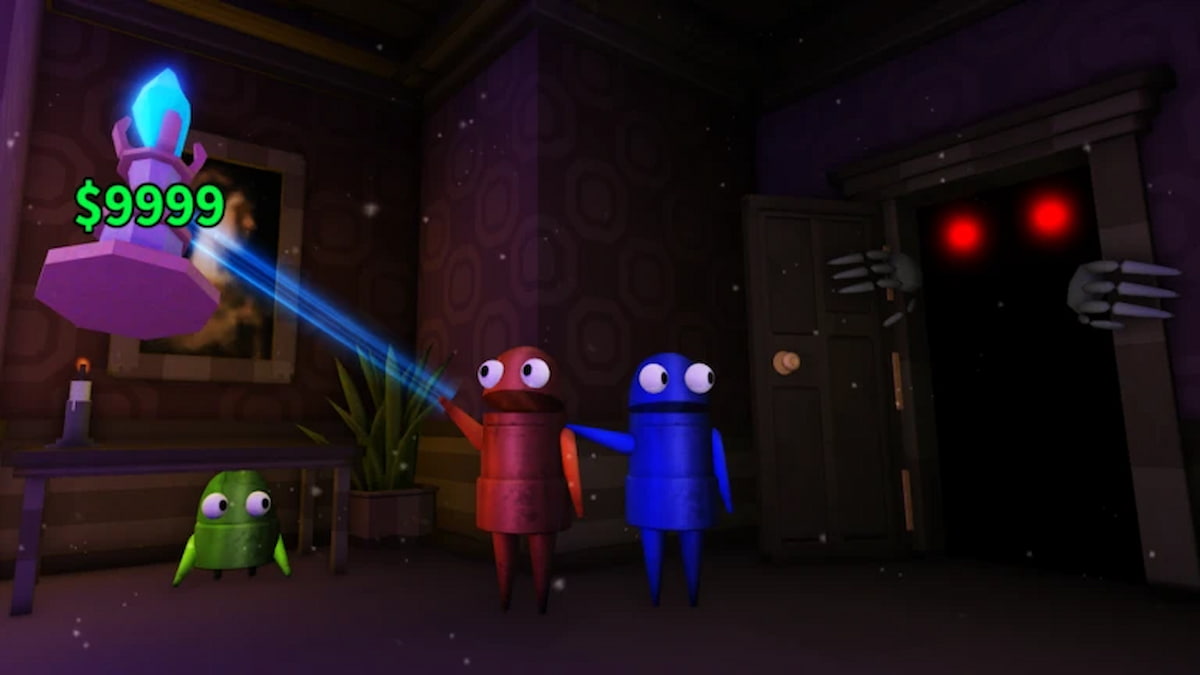

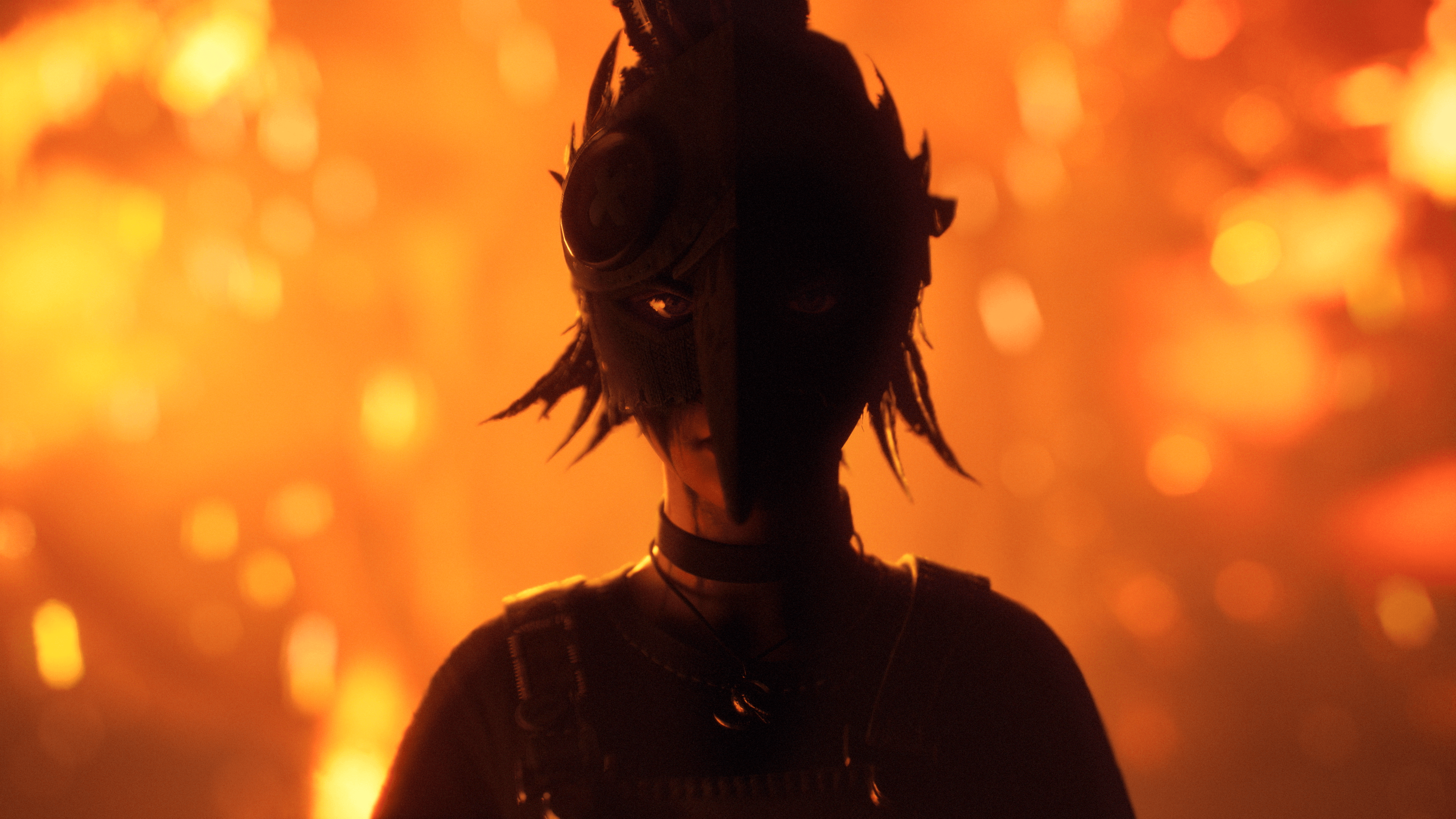

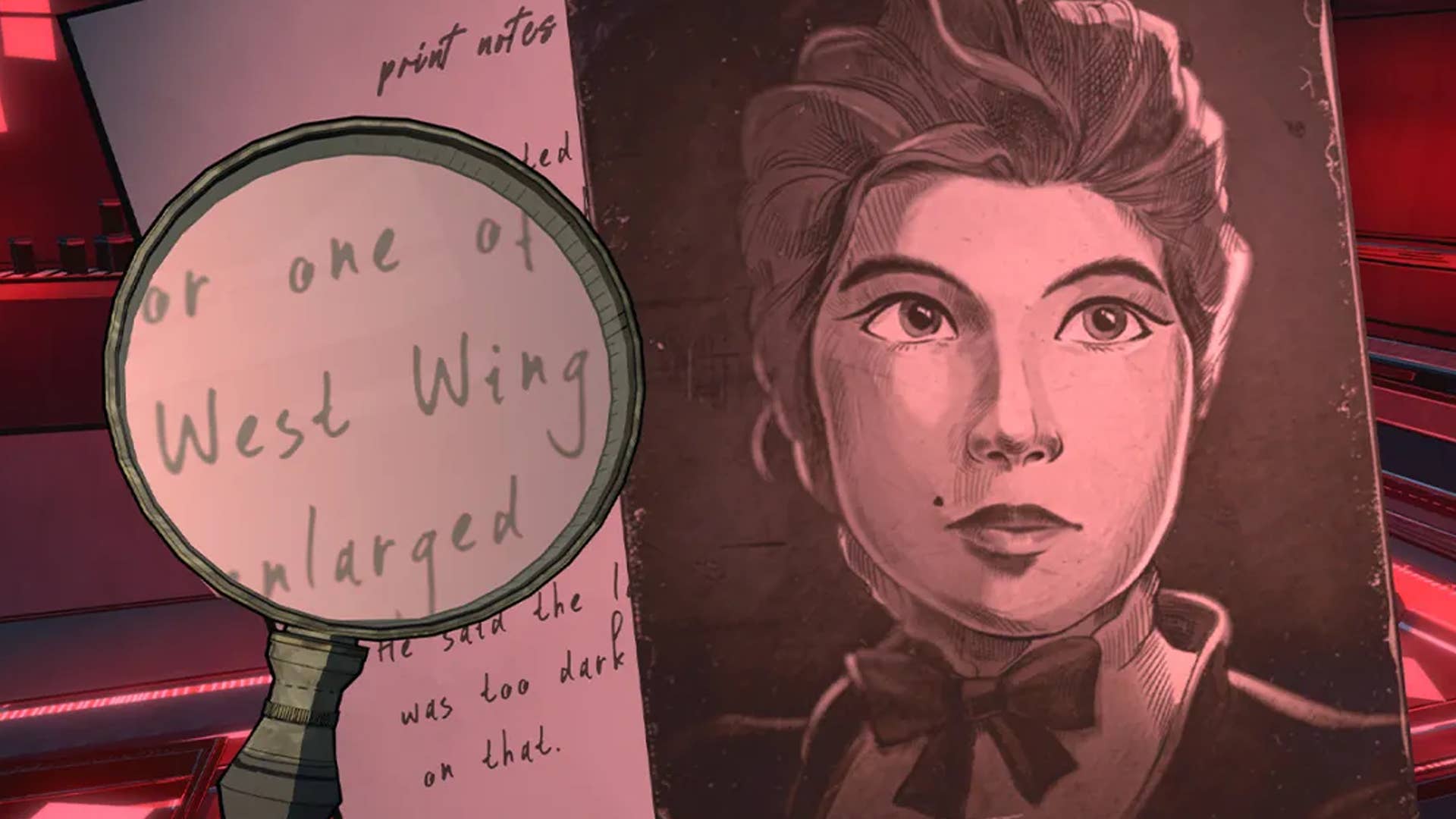

Microsoft published its Muse findings in science journal Nature, and posted two blogs and a video about it. Yet, it’s possible you may still have questions about what Muse actually does. Unlike the most popular generative AI models, which are infamous for stealing copyrighted work, Muse was built upon player data from Bleeding Edge, Ninja Theory’s lackluster arena shooter that came out in 2020, and was abandoned just 10 months later. The information collected from the game allowed Microsoft to train Muse on more than 1 billion images and controller actions, amounting to seven years of continuous gameplay.

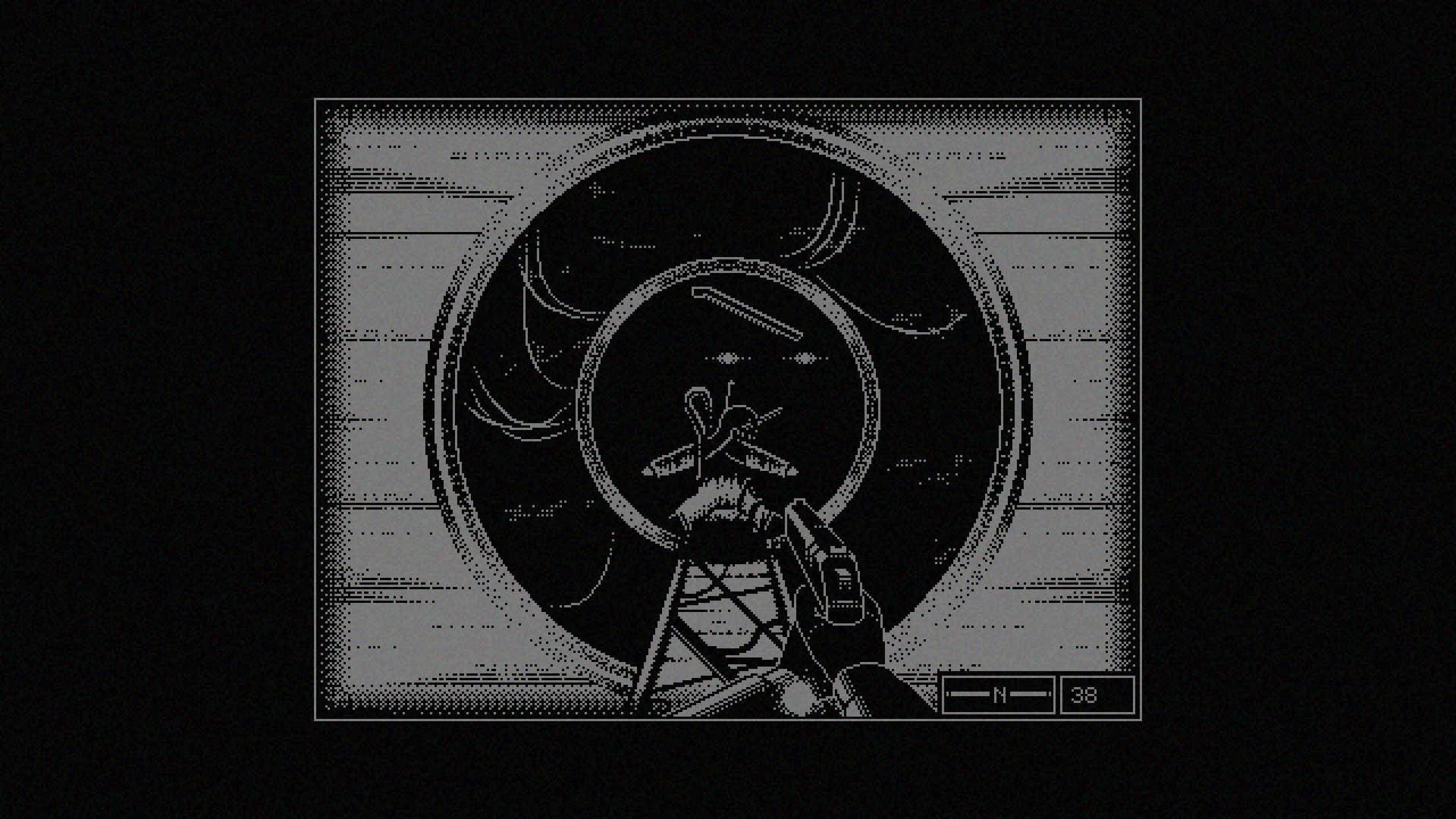

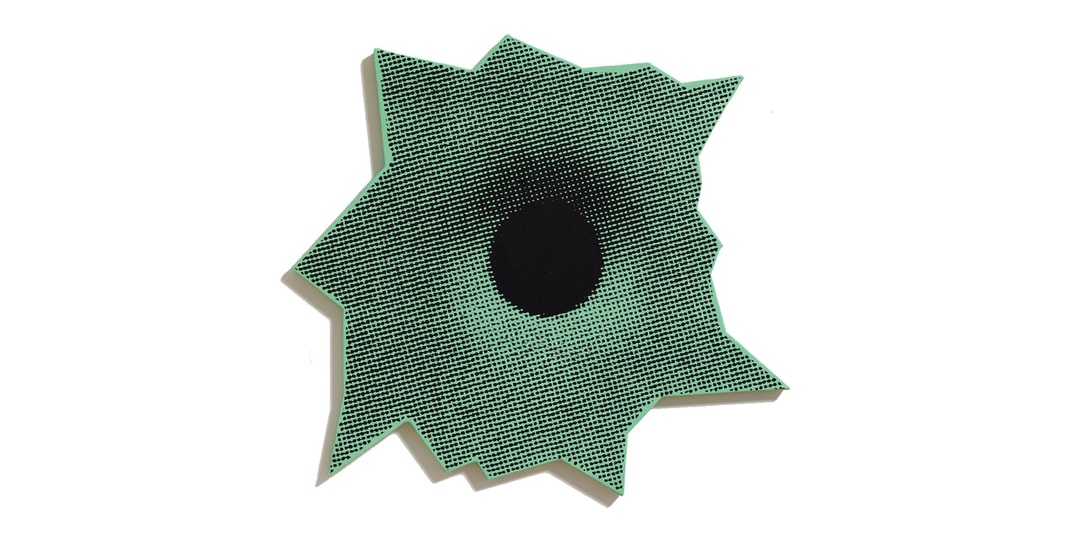

The resulting AI model is able to produce facsimiles (albeit, ugly ones) of Bleeding Edge gameplay, which Microsoft claims are proof Muse has a “detailed understanding of the 3D game world” and can “create consistent and diverse gameplay.” Microsoft chairman and CEO Satya Nadella shared a video on X teasing the eventual addition of Muse functionality to Copilot, the company’s GPT-4-based chatbot baked into Windows 11. Microsoft Gaming CEO Phil Spencer even painted a future where Muse might facilitate video game preservation.

“You could imagine a world where, from gameplay data and video, that a model could learn old games and really make them portable to any platform where these models could run,” Spencer said. “I think that’s really exciting. We’ve talked about game preservation as an activity for us, and these models and their ability to learn completely how a game plays without the necessity of the original engine running on the original hardware I think opens up a ton of opportunity.”

Ninja Theory studio head Dom Matthews was also quick to allay serious and obvious fears of Muse pushing the video game industry’s already-beleaguered workforce out of the picture.

“Technology like this is not about using AI to generate content but is actually about creating workflows and approaches that allow our team here of 100 creative experts to do more, to go further, to iterate quicker, to bring the ideas in their heads to life in a tangible form. I think the interesting aspect for us that is exciting is how can we use technology like this to make the process of making games quicker and easier for our talented team, so that they can really focus on the thing that I think is really special about games, which is that human creativity,” Matthews said.

Speaking with New Scientist, however, AI researcher and game designer Mike Cook said Muse is “a long, long way away from the idea that AI systems can design games on their own” due to the inherent limitations of its training on a single game.

“If you build a tool that is actually testing your game, running the game code itself, you don’t need to worry about persistency or consistency, because it’s running the actual game,” Cook explained. “So these are solving problems that generative AI has itself introduced.”

Even if human creativity isn’t at risk with Muse, as Microsoft says, it’s tough to balance hearing about this emerging technology knowing that many people are still reeling from Microsoft’s multiple mass layoffs. Presenting technology like Muse as experimental or somehow wholly conducive to creativity is safe and easy when its output looks like crap, which it unequivocally does at this point (not to mention, it’s trained on a single game). We just hope that Microsoft keeps it word when generative AI models improve to the point of challenging developer output.