The TV fantasy gold rush is over. Now maybe Wheel of Time can finally be itself

When Prime Video’s The Wheel of Time debuted in late 2021, it was just one of many prestige TV shows flooding the market. Studios, networks, and tech companies alike were throwing a staggering amount of resources at their respective streaming platforms in an effort to stockpile glossy, must-see programming guaranteed to boost their subscriber numbers. […]

When Prime Video’s The Wheel of Time debuted in late 2021, it was just one of many prestige TV shows flooding the market. Studios, networks, and tech companies alike were throwing a staggering amount of resources at their respective streaming platforms in an effort to stockpile glossy, must-see programming guaranteed to boost their subscriber numbers. Within this mad dash for streaming supremacy, a separate race was run: the scramble to score the next Game of Thrones-level fantasy blockbuster. A series so irresistible that everyone would tune in.

As strategies go, it was pretty smart. The fantasy genre is full of popular preexisting IP that’s arguably a safer bet than an untested original idea, and often comes with a ton of built-in spinoff potential to boot. It’s also inherently splashy (lavish costumes, sets, and VFX scream “premium”) and — if packaged just right — can even lure in folks who wouldn’t otherwise fuck with snow zombies or dragons. In short? A fantasy show can do a lot for a platform’s performance and perception, which is why so many of them backed the genre. HBO leveraged its existing rights agreements and greenlit a Thrones spinoff, House of the Dragon (after another, famously expensive false start). Netflix put its chips on Shadow and Bone, The Witcher, and The Sandman. Disney — primarily focused on its fantasy-tinged Star Wars property — still managed to crank out Willow and Percy Jackson and the Olympians. And Amazon went all in on The Wheel of Time and The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power.

But fast-forward to 2025, and the gold rush is over. Streaming platforms are shifting away from subscriber growth as the ultimate metric for success. The days of the blank-check prestige production are over (if they ever even existed). Hell, shows are getting axed before they even enter production: Disney and Hulu recently confirmed they’re not moving forward with a Court of Thorns and Roses adaptation, despite those books being the fantasy IP right now.

Which begs the question: What does all this mean for the state of fantasy TV, and the shows still standing? What becomes of a series like The Wheel of Time — currently on its third season — now that it’s outlived the corporate game plan that helped get it greenlit?

[Ed. note: This article contains spoilers for The Wheel of Time season 3, episode 4, and touches on some events that happen later on in the book series.]

When Amazon executive chairman Jeff Bezos was still CEO, he supposedly ordered then-Amazon Studios boss Roy Price to find him a crossover hit in the same vein as HBO’s global phenomenon. This led to a lot of projects getting the thumbs up, including The Wheel of Time. But here’s the thing: The Wheel of Time is not — and will never be — Game of Thrones.

Sure, Robert Jordan’s fantasy novels superficially have a lot in common with George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire tomes (which served as the basis for Game of Thrones). Aside from their faux-medieval settings, both involve plenty of court intrigue and political wheeling and dealing. And unlike J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and its associated works, they both acknowledge the sexual appetites of their respective casts. Yet there are also incredibly pronounced differences between these two fantasy sagas — so much so that showrunner Rafe Judkins felt the need to manage Amazon execs’ expectations when they hired him.

“This show and the books are not like Game of Thrones. I said that to Amazon right up front,” Judkins recalled back in 2021. “I was like, If you are looking for the next Game of Thrones, this isn’t it. What I’m gonna pitch you is a series that is really different.”

He’s not wrong, either. Take the sex stuff I mentioned earlier: Yes, Jordan’s books reference characters getting it on — Jordan’s series also has a wild subplot that lands somewhere between BDSM and outright rape — but it’s all presented in relatively chaste, indirect terms. The word “sex” (much less “fuck”) is never used, and unlike in Martin’s works, the act itself typically happens between paragraphs. The Wheel of Time show follows suit — and, in some cases, actually tones down some of Jordan’s more “adult” content. Not only is there none of the sibling-on-sibling doggy style or foreground blowjobs that characterize HBO’s Westeros adaptations, even the non-sexualized nudity Jordan describes (for example, during Aes Sedai testing) is missing from the Prime Video version of The Wheel of Time.

The Wheel of Time books are also a damn sight less “TV ready” than A Song of Ice and Fire. Don’t get me wrong: Game of Thrones showrunners David Benioff and D.B. Weiss had their work cut out for them wrangling Martin’s sprawling source material into a coherent, easy-to-digest series. The fact they completely overhauled the show’s original, unaired pilot is a testament to just how tough it is to make sense of A Song of Ice and Fire’s sheer volume of characters, locations, and lore. But compared to the challenge Judkins and his team faced with The Wheel of Time, Benioff and Weiss got off easy. They were whittling down five novels (plus a napkin’s worth of bullet points), not 15 — and 15 subplot-heavy novels, at that.

It’s a similar situation to the one The Rings of Power showrunners J.D. Payne and Patrick McKay currently find themselves in: So. Much. Material. Their assignment is crafting a cogent multi-season epic out of back matter paragraphs (at best) lifted from Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy and its appendices. So, they’ve got a bunch of heroes and villains and a pile of massive plot beats to hit — most of them separated by both an unwieldy in-universe timeline and sweeping geography — and no pre-baked narrative to hang any of it on. Oh, and everybody (including, presumably, Amazon) is expecting Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings movies, which are (for reasons the above should make fairly obvious) an entirely different beast. Fortunately for Judkins, he doesn’t have to deal with those last two headaches; however, he’s surely sympathetic to Payne and McKay’s battle with the IP bulk.

Still, everyone’s got a different burden in the fantasy streaming revolution. And for Judkins, it’s how Jordan’s story requires so much establishment compared to other properties. You can communicate the setup for something as story-critical as Daenerys Targaryen’s quest for the Iron Throne with just a few lines of dialogue explaining her exile. There’s no need to get too deep in the weeds regarding Robert’s Rebellion and the Targaryen dynasty’s downfall. Equally, a super-brief prologue is all you need to get Galadriel, Halbrand Sauron, and the rest of the Middle-earth gang’s Second Age adventures up and running, because (thanks to Jackson’s trilogy) audiences are already familiar with their older, Third Age incarnations. But so many of The Wheel of Time’s biggest payoffs fall flat without the necessary preamble. That’s why season 2’s climactic Heroes of the Horn moment is so underwhelming: because the show never properly explains who these guys and gals are, or why they matter before they flank Mat. Similarly, the true motivations (and origins) of the second season’s Seanchan baddies are presumably frustratingly opaque to anyone who hasn’t read Jordan’s second Wheel of Time novel, The Great Hunt.

Yet most of all, what separates The Wheel of Time — and every other gold rush fantasy series apart from House of the Dragon — from Game of Thrones is their differing approach to genre tropes. With A Song of Ice and Fire, Martin very consciously zigs where escapist fiction in general, and Tolkien’s Middle-earth mythos in particular, would zag. By contrast, Jordan openly admitted to channeling (pardon the pun) The Lord of the Rings early on in The Wheel of Time, and it’s apparent in everything from the idyllic, Shire-like Two Rivers to uncrowned king Lan.

The upshot of this is that the moral polarity of Jordan’s universe (like many fantasy universes) skews positive. His heroes are unequivocally heroic; even protagonist Rand — who spends most of The Wheel of Time teetering on the brink of madness — ultimately wants to do the right thing. And such nobility is typically rewarded, even if the occasional supporting character gives their life along the way. Meanwhile, A Song of Ice and Fire gleefully subverts this moral status quo. Storybook heroism gets you killed in Westeros, and gets less done than well-intentioned pragmatism anyway.

Neither of these approaches is right or wrong, but there’s no denying that part of Game of Thrones’ popularity was thanks to emulating Martin’s anyone can die, everyone can lie credo. Yet this approach only works when wedded to the right IP. Indeed, some of The Wheel of Time’s biggest bum notes come from aping Game of Thrones’ borderline nihilism, resulting in an oddly gritty Two Rivers, a Mat Cauthon who murders an entire family, and a child-killing Queen Morgase. Were these incongruous elements Judkins’ way of trying to reach the Thrones-enamored audience he knew Amazon expected him to lure in? If so, it didn’t work, and was probably never going to work.

And that’s what it all boils down to, really: The Wheel of Time was never the right IP for Amazon. It’s maybe not even the right IP for TV more broadly. On paper, it’s a no-brainer: a bestselling saga with complex characters and a rich mythology. In practice, it’s ill suited to easy adaptation — and that’s without a subscriber-count arms race hanging over production. True, The Wheel of Time hasn’t been a total bust for Amazon. Reviews for all three seasons are solid, and viewership stats are very healthy. It’s not, however, the zeitgeist-shaping, Prime Video ubiquity-creating franchise Bezos supposedly demanded. But like I said at the top: That doesn’t matter so much anymore, now that the fantasy streaming gold rush is done.

And if shows like The Wheel of Time don’t have to be something they’re not — namely, Game of Thrones 2.0 — maybe now they can fully, truly be their best selves. They can let their freak flags fly (as The Rings of Power has increasingly done) and focus solely on capturing the spirit of their own source material in a different medium, without filtering it through someone else’s. To date, that’s something The Wheel of Time has only fitfully accomplished, and in almost every instance, it’s done so by following its own playbook, not the post-Game of Thrones fantasy TV template.

Consider season 1’s most striking sequence: the final moments of Rand’s pregnant mom, Tigraine, on a snowy battlefield in episode 7. This isn’t a direct pull from Jordan’s first Wheel of Time book, The Eye of the World, which only covers some of this information via dialogue, leaving the rest for later volumes. Yet presenting this as a flashback was absolutely the right call for the Wheel of Time show, as it communicates the truth about Rand’s parentage (and identity as the Dragon Reborn) far more viscerally than slavishly following Jordan’s prose — or Game of Thrones’ flashback-skeptic sensibility — ever could have. Without spoiling things, there’s another “invented” flashback in season 3’s finale that does a similarly impressive job of fleshing out the festering rivalry at the heart of Tar Valon’s strife. It’s something else Jordan didn’t need to cover firsthand on the page that viewers do need to see on the screen.

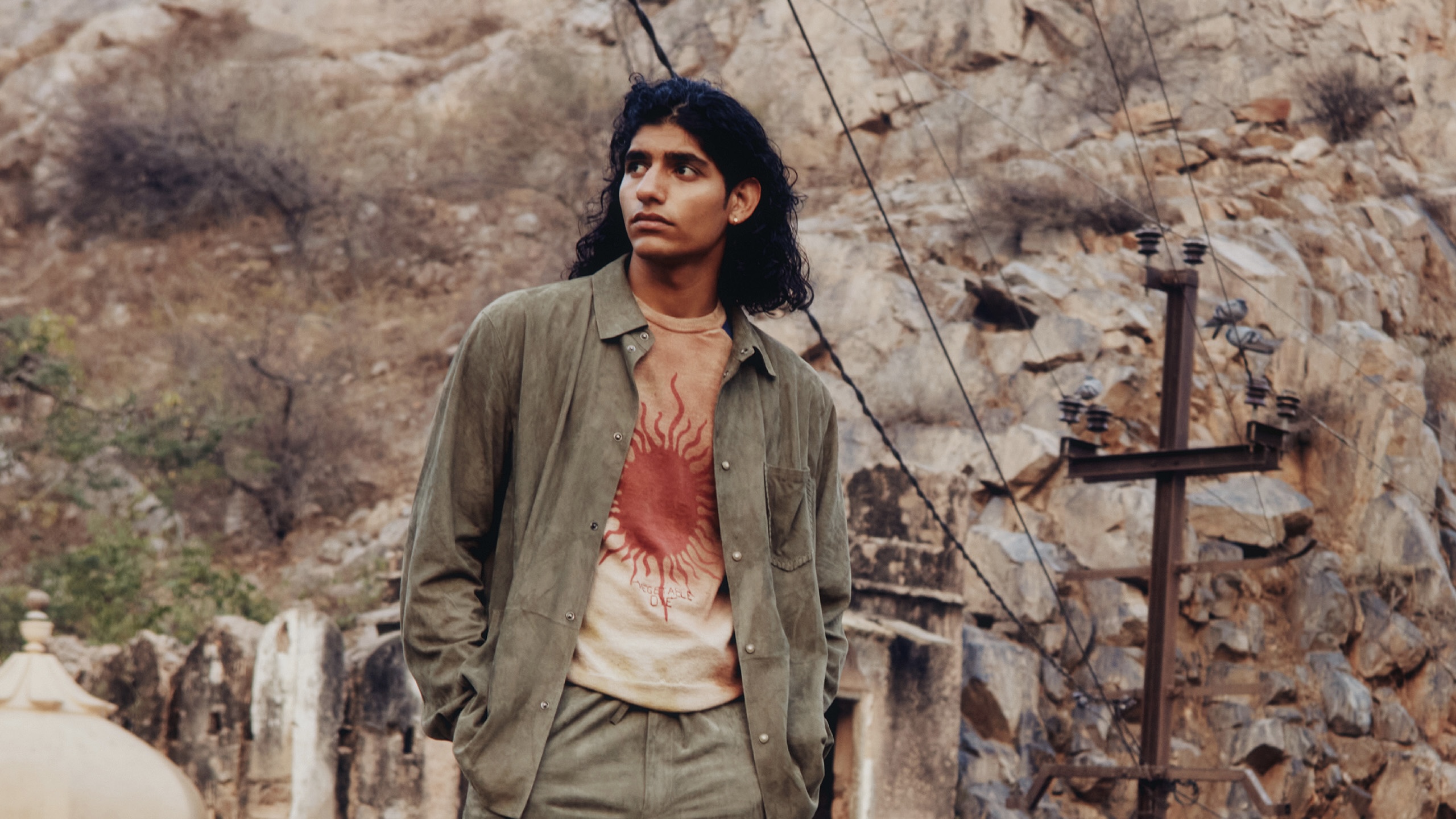

Rand’s revelatory Rhuidean vision quest in season 3, episode 4 is a similar proposition. This event is in Jordan’s books, but the way Judkins and director Thomas Napper stage it could only work on screen — and only in this specific story. They succinctly cover both the Aiel’s secret history and Lanfear’s origin story, while also adding (or emphasizing) visual and audio details — most notably, the Song of Growing ritual mentioned elsewhere in Jordan’s writings — that heighten its sensory impact. The combined effect of Lanfear’s sci-fi research lab floating in the sky, the chanting proto-Aiel in the fields below, and the existential, sky-crumbling horror that follows is genuinely haunting. More than that, it’s something you couldn’t manifest on the page, and is too flat-out strange to mimic in a show like Game of Thrones. Could more moments of undiluted Wheel of Time weirdness be on the horizon in future seasons? We can only hope.

The same goes for the dizzying supercut of Moiraine’s possible futures that runs in parallel with Rand’s journey into the past: It’s a major embellishment on the part of Judkins and Napper. Jordan left the alternate lives (and deaths) of Rosamund Pike’s Aes Sedai in the margins; in contrast to the protracted, granular depiction of what Rand saw, we only get the general gist of Moiraine’s ordeal in the books (and secondhand, at that). On the page, that plays — fostering a sense of mystery around a key supporting character’s fate. But in a screen adaptation, it’s practically a sin to leave something like this to viewers’ imaginations. Judkins and Napper clearly get that, and the swirling 360-degree montage they deliver is a powerful illustration of what can happen when an adaptation uses its source material as a starting point, not a final destination. Not for nothing, in its sheer bravura dynamism, it also puts the more pedestrian prophetic visions in House of the Dragon’s latest season to shame, too. More, please.

Let’s also keep our fingers crossed that there’s less impetus (self-imposed or otherwise) for Judkins and co. to imitate the R-rated romance of The Wheel of Time’s raunchier competitors. Admittedly, Judkins has maintained from the start that he wasn’t interested in chasing the same risque thrills as Game of Thrones, The Witcher, A Court of Thorns and Roses, or their ilk. But I have to imagine that not falling too far short of viewers’ expectations on this front is what resulted in The Wheel of Time’s couples (and throuples) content shooting for an awkward middle ground between Jordan’s sweet-natured suggestiveness and all-out orgies.

No, it hasn’t stopped the rise of an online thirst brigade — and if anything, it’s apparently the right amount of friction (pun fully intended this time) for more conservative viewers. But still: It’s one of the more glaringly clunky aspects of the show that’s easy to fix when matching other series’ heat is less of a going concern. More than that, it’d give the Wheel of Time team more room to elaborate further on something uniquely Jordanian: delightfully bonkers romantic dynamics. Yes, The Lord of the Rings’ interspecies hookups have a star-crossed charm and Game of Thrones’ and House of the Dragon’s incest is queasily fascinating, but they’re not a patch on the sublime unorthodoxy of many of The Wheel of Time’s canonical pairings.

We’re seeing some of this in season 3, with Rand and Lanfear’s dreamscape tryst. This naughty affair doesn’t just get decent mileage out of the “bad girl” trope — it also draws a substantial amount of juice from Lanfear being less in love with Rand than with his reincarnated soul. There’s so much more material like this that future seasons could get into, from Lan and Nynaeve switching up stereotypical gender roles via Sea Folk role-play to the vaguely Gone Girl-esque scenario Mat ends up in. Let’s also not forget the books’ infamous quad only hinted at in the show so far.

Why not lean hard into all of this stuff (and more besides)? After all, the time is ripe for it. The streaming gold rush is over. Now, shows like The Wheel of Time can truly begin.