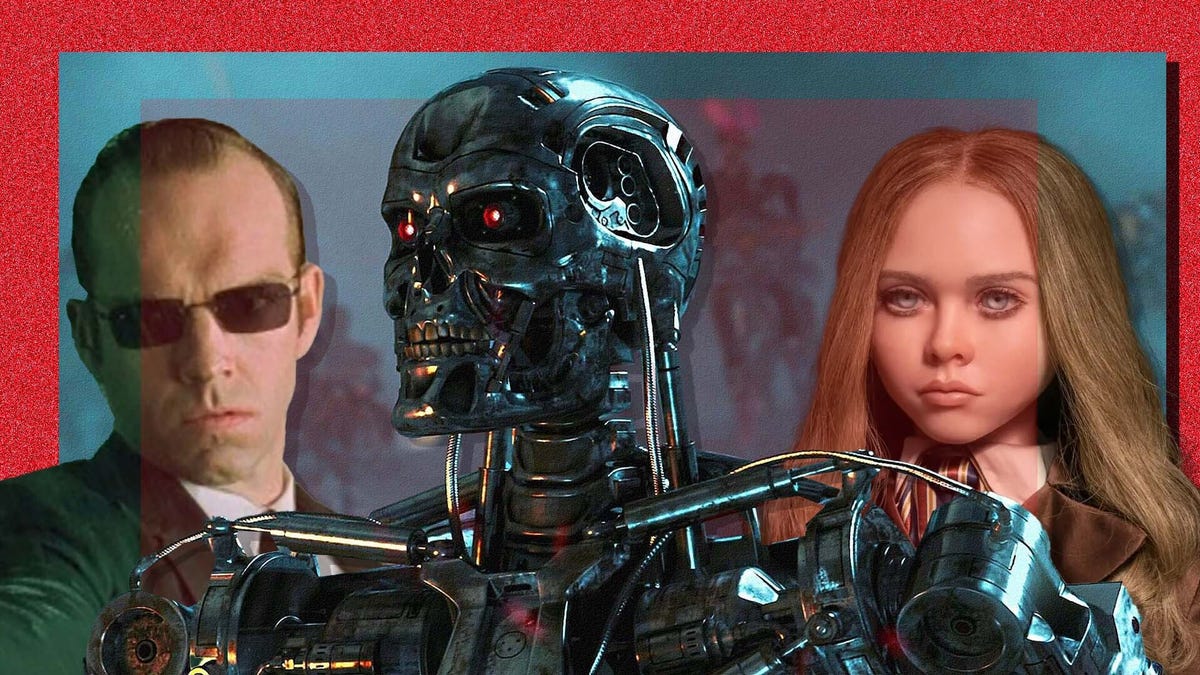

There’s so much to untangle in Sinners’ real ending

Even before the news broke about the unconventional rights-reversion deal Black Panther writer-director Ryan Coogler negotiated with Warner Bros. for his horror movie Sinners, the movie was already one of 2025’s most-discussed releases. Michael B. Jordan’s dual role as twin gangster brothers Smoke and Stack, the movie’s bold themes around racial identity and community, Coogler’s […]

Even before the news broke about the unconventional rights-reversion deal Black Panther writer-director Ryan Coogler negotiated with Warner Bros. for his horror movie Sinners, the movie was already one of 2025’s most-discussed releases. Michael B. Jordan’s dual role as twin gangster brothers Smoke and Stack, the movie’s bold themes around racial identity and community, Coogler’s intense approach to creature-feature violence, and a particularly ambitious, gorgeous scene connecting the past and present through music all opened up different avenues for conversation. And with so much to talk about, the word of mouth has kept the movie in theaters, even though it’s now also available for home viewing on digital platforms.

But there are still aspects of Sinners worth unpacking, especially as the digital release invites a whole new audience to catch up with the conversation. In particular, there’s a lot to draw from in the movie’s extensive, story-changing post-credits scene — but that sequence overshadows the movie’s actual ending, and what happens to one of the Smokestack twins. Sinners’ ending is satisfying on a surface level, but the more you look at it, the richer it gets. Let’s dig in.

[Ed. note: End spoilers ahead for Ryan Coogler’s Sinners.]

In Sinners, twin brothers Smoke and Stack return to their Mississippi Delta hometown after years spent working for the Chicago mob. It’s 1932, and the twins’ interaction with local white businessman Hogwood (David Maldonado) suggest an era where race relations are frosty and polite in public — at least, between white and Black people with money. But other elements in the movie make it clear that systemic bigotry lives on unabated, and that the supposedly disbanded Ku Klux Klan is still active and empowered. The Klan isn’t an active presence for most of the movie, but a passing glimpse of Klan robes in a farmhouse (a touch so telling in that particular moment that it could be the subject of a whole separate essay) is a reminder of what’s hiding behind genial, fixed smiles like Hogwood’s.

Most of Sinners deals with a different kind of secret predator. Smoke and Stack buy a defunct sawmill from Hogwood and convert it into a juke joint intended expressly for the Black community. When the twins’ cousin Sammie (R&B/gospel artist Miles Caton) plays his original blues music there, magical things happen, and a vampire, Remmick (Jack O’Connell), sets out to acquire Sammie. As Remmick lays siege to the juke joint, nearly everyone working or dancing there either dies, or gets turned into a vampire, then dies. Stack himself gets vamped, and repeatedly tempts Smoke to embrace vampirism, resume their old partnership, live forever, and become part of a new and more powerful community.

Smoke refuses, but lets Stack escape with his girlfriend Mary (Hailee Steinfeld), and flee Mississippi together. Only Smoke and Sammie survive the night, and Sammie leaves town. Smoke stays behind to meet Hogwood, who shows up in the morning with a small army of Klan members, all armed, smug, and geared up to kill the brothers and burn down the juke joint.

The vampires told Smoke this attack was coming — the warning is part of Remmick’s “come join us and escape all this racist nonsense” pitch. So Smoke is prepared, and he guns down Hogwood and his buddies, but he’s fatally shot in the process. He does not seem surprised, or even particularly regretful about his fatal wound, especially since, as his consciousness fades, he sees his lover Annie (Loki’s Wunmi Mosaku) waiting for him, nursing their infant who died years ago.

There are a lot of ways to read Smoke’s choice to stay behind and fight Hogwood and the Klan. We’ve seen that he’s a proud man who’s determined to protect the fierce reputation he and his brother have built together, and he’s willing to use casual violence in that cause. It’s worth wondering what the two of them might have done if they’d learned about the coming attack some other way, in a version of this story with no vampires: It’s hard to imagine them backing down from this fight and letting the Klan burn their business, even if the alternative was a pyrrhic face-off.

But Smoke clearly isn’t defending the juke joint because he thinks he has a future there. Even if he does believe it’s possible he’ll survive the fight with the Klan, his brother is gone, his clients and community are gone, his staff is gone. He’s fighting back on principle, unwilling to let the racists have even the token victory of burning the empty venue and his abandoned dream. And it seems far more likely that he goes into that fight expecting to die, and just hoping to take down as many murderous, destructive local assholes as he can.

There’s certainly a “nothing left to lose” quality to Smoke’s last stand. In a society as stacked against Black citizens as 1932 small-town Mississippi is, it’s easy to imagine a history for the Smokestack twins where they left for Chicago and joined the Mob not just to join the big time and make serious money, but to find a place where their pride and ambition wouldn’t constantly run up against small-minded, violent despots like Hogwood. Part of that thinking would have been the understanding that any time they stood up to white oppression in Mississippi, they risked getting lynched.

So we can see Smoke indiscriminately gunning down Klan members as a final big cathartic blowout, a way of finally letting loose against the people who’ve been belittling and oppressing him since he was born, now that there isn’t anything left for them to take except his life. It also seems pretty likely that there’s an element of despair to this climactic gesture: Having lost his brother, Annie, his community, and his future, he’s certainly angry, hurt, and frustrated. He was likely planning on going out in a blaze of glory on behalf of all of the people he’s lost, who’ve also dealt with white oppression their entire lives. And if he joins them in the process, he seems willing to pay that price.

But there’s another wrinkle to all of this that feels hidden under his other motivations. What if Smoke goes into that fight in part because he knows he’s likely to die fighting the Klan, and he knows he needs to die or he’s going to end up joining his brother as a vampire?

From everything we see throughout Sinners, Smoke and Stack are inseparable. They’ve shared all their biggest traumas, their secrets, and their plans. One of the cruelest parts of Sinners is the way, once Remmick turns Stack into a vampire and draws him into their weird psychic collective, Stack immediately tries to leverage their past to lure Smoke into willingly accepting death. He uses the language of their shared connection and history, and claims he just wants them to be together, but he’s also clearly serving his master’s agenda first and foremost, and trying to manipulate his brother.

Smoke certainly knows that if he survives and tries to make a life for himself, Stack will be back for him. Maybe he’ll keep trying to persuade Smoke to come willingly. Or maybe he’ll just take the first opportunity to grab his brother and convert him by force. And maybe, with Annie dead, Sammie gone, the community shattered, and the juke joint out of business, Smoke knows he won’t be able to resist the temptation. Maybe on some level, dying taking down as many Klan members as possible is his way of protecting his own soul — making his suicide mean something by taking a stand against the Klan, and ensuring at the same time that Stack will never get him.

As a literal interpretation of Smoke’s private war and bittersweet death, that’s a lot to contend with on its own. The movie’s ending just gets more complicated when you factor in how Coogler uses vampirism throughout the movie as a metaphor for colonization and white assimilation of Black culture.

Coogler has made it clear that he does sympathize with Remmick, who has himself been the victim of majority oppression. And in Coogler’s interpretation, Remmick is being sincere when he paints a picture of his vampire band as a colorblind, prejudice-free community. Sinners doesn’t portray them as simple, black-and-white villains. But Remmick’s community forces everyone to move in lockstep, due to their shared mind: They all sing the same songs, experience the same feelings, see the world the exact same way, and even share their deaths, through their vampiric connection. There are no meaningful differences between them, which means their individuality is limited.

When Stack tells Sammie in the post-credits scene that he’s found complete freedom as a vampire, it’s only because Remmick is gone, and Stack and Mary aren’t part of his assimilation anymore. And when Smoke chooses to die fighting the Klan rather than joining his brother, he’s choosing an individual death over a collective one, and self-determination over being pulled into a kind of hive-mind where he won’t fully own himself anymore.

All of this is just speculation: We can only really guess at what Smoke is thinking, given everything we’ve seen of him throughout the movie. But finding a way to go out proud, loud, and absolutely on his own terms is consistent with the character Coogler shows us throughout the movie. It’s clear he sees Stack’s promises and lures as both a temptation, and anathema. It’s clear he doesn’t want anyone else defining his life for him, not even his precious brother. The end of Sinners plays like a dark victory for Smoke either way, because he gets to choose his death for himself. As much as he and Stack loved each other, his brother might not have been able to resist taking that option away from him.

Sinners is still playing in some theaters nationwide, and is available for online rental or purchase on Amazon, Fandango, Apple TV, and other digital platforms. The DVD, Blu-ray, and 4K release is coming July 8.

.jpg)