Wanderstop is so much more than just brewing tea — but that part’s good, too

A few years ago, a sound bite went viral on TikTok: “Darling, I’ve told you several times before, I have no dream job. I do not dream of labor.” As writer Caitlyn Clark put it in Jacobin at the time, it’s no surprise that the statement resonated with people: a “tighter labor market,” Clark wrote, […]

A few years ago, a sound bite went viral on TikTok: “Darling, I’ve told you several times before, I have no dream job. I do not dream of labor.” As writer Caitlyn Clark put it in Jacobin at the time, it’s no surprise that the statement resonated with people: a “tighter labor market,” Clark wrote, put increased pressure on workers over the past several years. It’s an increased strain that’s put more and more money in the pockets of the richest among us, yet it hasn’t created better workplaces or a better world for the rest of us. And I’ve been thinking about this phrase — “I do not dream of labor” — as I play developer Ivy Road’s Wanderstop. Though the foot on protagonist Alta’s neck is not one of a corporation, but of an individual drive to succeed at all costs — certainly influenced by culture at large — she is ultimately worn down so severely that she can no longer continue. She’s forced to rest, to engage in a less laborious life. But her new life does, indeed, involve labor.

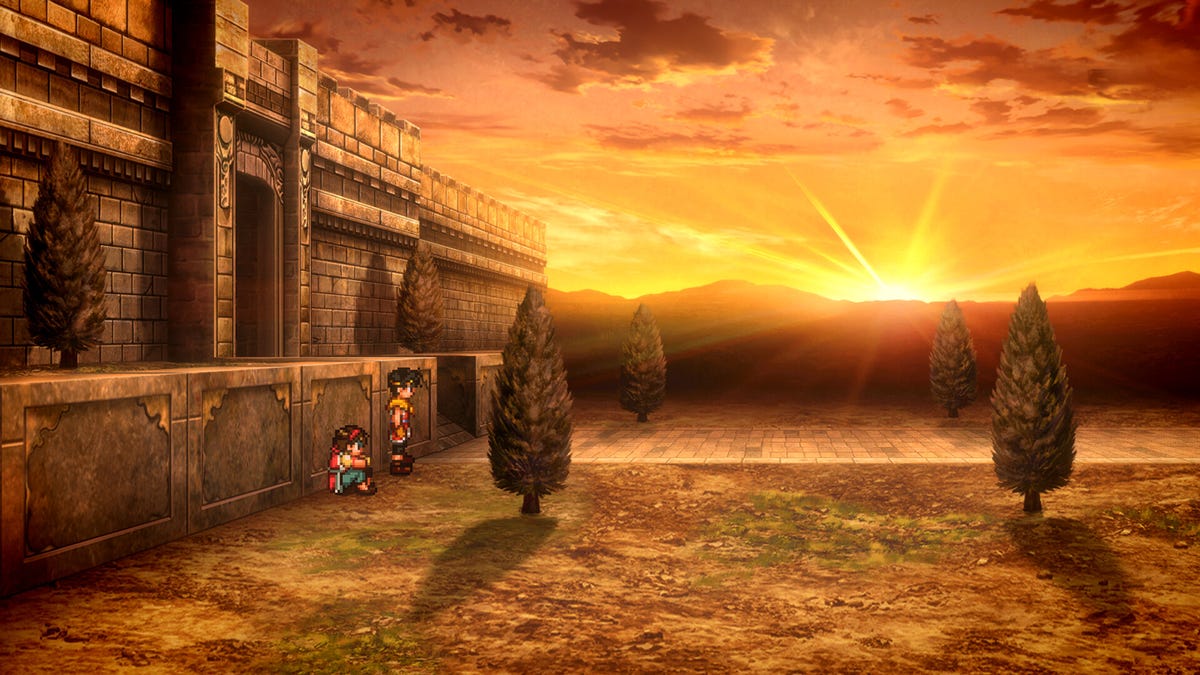

Wanderstop begins with prolific and successful fighter Alta failing. It’s her first major failure — something she vowed would never happen to her. She had gone to a forest in search of a woman who can train her up, bring her back to her peak form, but the journey didn’t go as planned. Where she lands, instead, is a tea shop. The affable tea shop owner, Boro, plucked her from the forest after she collapsed, no longer able to wield her sword. She doesn’t want to stay, but she also can’t leave: Every time she tries, she collapses. She can’t hold her sword. And so, she does stay. People start to trickle into the tea shop and its surrounding clearing, so she makes them tea.

At this point, Alta probably does dream of labor — the labor of training and fighting for redemption. But over the course of roughly a dozen hours, she begins to let go of that compulsion. Alta trades one type of labor for another: one that’s more caring, slow, and, yes, healing. Wanderstop’s tea shop does not operate for profit. The land around the shop provides everything necessary to make a cup of tea, aside from the tea-making contraption itself. This is where Wanderstop pulls in its cozy gaming elements — the comforting repetition of a farming simulator, with a little twist, is the backbone of its gameplay. Working as Alta, I must plant seeds in specific formations to produce different sorts of plants to harvest both seeds and fruits; the seeds keep the farming running, and the fruits I use to brew tea. I explore the forest for tea leaves, sweep up piles of dead greenery, and snip invasive vines. The tea leaves get dried, and then I can make tea for the different people who pass by.

Each of these people stays briefly at the tea shop, their own stories playing out with every interaction. At first, Alta is desperate for labor — begging people to let her make them tea. But that attitude shifts with each cup of tea she makes as she grapples with her dark past, something she’s long blocked out. Her new form of labor, the act of foraging for ingredients, growing essential fruits, and brewing tea to serve to others, is what’s healing her; she’s engaging in her community in a useful, thoughtful way. Her labor makes a difference not only for herself, but for others, too. Separated from an exploitative system, her work means something more. Beyond the narrative, Wanderstop largely succeeds at engaging with this ideology through its gameplay. I’m not necessarily rewarded in any way for brewing tea for people in the clearing, other than learning their own stories and preferences. This doesn’t unlock tools to do the job better or faster; I brew tea the same, complicated way each time, using a big ol’ contraption that requires several steps of manual labor.

There’s no real time limit on appeasing these customers; they’ll stay for as long as necessary to get their cup of tea. If you wanted, instead, to brew a dozen cups for yourself or Boro, that’s quite all right. Maybe you’d rather play around with decorations, or test out new combinations of patterns to grow other plants. That’s OK, too. But Wanderstop is a game, and there are still plenty of game-y elements that do detract from its themes. It’s pretty aggressive with its notification icons, for one, so it’s always immediately clear that there’s a new customer to serve or something another wants to tell you. For instance, there’s an early character who’s an eager knight placed under a curse. After one interaction, he sets back out into the forest to complete some task — but in my playthrough, he returned not even a minute later ready to push his own story further, a big yellow exclamation mark over his head as he rushed back toward me. The urgency of these sorts of interactions is entirely at odds with everything else in the game. There’s a meaningful friction in the narrative that makes Wanderstop memorable, but that friction isn’t replicated in the slightest with the gameplay. I can understand why, because adding that friction, be it simply through more time spent waiting or removing notification icons, risks players becoming frustrated and quitting. But it’s a friction that the game could have benefited from to better serve Wanderstop’s unique framing.

This all comes back to the idea of dreaming about labor — or not. I don’t dream of labor within the system we live under now, but that doesn’t mean I don’t dream about labor at all. The future I dream of isn’t one without friction, but one that ensures a slower, happier life for my community, even if that means doing the work. Wanderstop feels the most meaningful when it focuses on that.

Wanderstop will be released March 11 on PlayStation 5, Windows PC, and Xbox Series X. The game was reviewed on Steam Deck using a pre-release download code provided by Annapurna Interactive. Vox Media has affiliate partnerships. These do not influence editorial content, though Vox Media may earn commissions for products purchased via affiliate links. You can find additional information about Polygon’s ethics policy here.