What I Found Driving Down Highway 61

This essay is part of The Great Escape, Atlas Obscura’s soon-to-launch guide to American road trips, featuring more custom itineraries, regional highlights, and practical tips for travelers hitting the road together. See where Aaron stopped. Highway 61 is known as “The Blues Highway” as it makes its way from New Orleans to Memphis, following the Mississippi River through lands forged over eons. From the coastal swamps of Louisiana to the alluvial plains of The Delta, the highway connects these landscapes to the human tales etched into the soil—telling the story of the Deep South through a journey of migration, transformation, and enduring spirit. In New Orleans, where I was born and raised, Highway 61 was the end of my known world. It was a road of short-stay motels, pawn shops, bingo parlors, and a pervading sense of danger. It was the boundary of my childhood, of all that was safe and familiar. Years later, as an adult, I would come to know the highway as a conduit to the past, an artery of profound historical and cultural significance, invention and reinvention, of human dreams pinned to its asphalt, ever following the river like an acolyte to the great hand that carved both into the mythos of the South. In Louisiana, the highway buckles and keeps time on car tires, skipping like scratches on old vinyl. Mississippi is its beating heart, where the blues was born, sung with lament and anger and hope in hollers, shouts, and chants. In Memphis, after the Great War and the Great Migration, the road brought blues music to the big stage, at home on Beale Street, where it dug in its heels and grew roots that couldn’t be plucked. To drive along this highway is to make a pilgrimage through the South, its history and its legends. And so, because the river runs south and because all journeys are eventual homeward journeys, I begin my road trip in Memphis, the Delta’s spiritual, northernmost terminus. After feasting on some of the region’s best soul food and barbecue, I leave Tennessee and cross the border into Mississippi, the land flat and low, all horizon, its cotton fields scorched under the midday sun and the tarred road shimmering with excess heat. Past Tunica, barely an hour south of Memphis, the highway passes through Clarksdale—the epicenter of Delta blues music. Here is where Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil, and where Roger Stolle opened Cat Head Delta Blues & Folk Art to help revive interest in a dying town, where Red’s juke joint remains one of the last of a fading breed of original blues venues. Onward the Delta stretches wide and thin between the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers. I stop in a famed family run pottery shop, and at Doe’s Eat Place I have some of the best steak I’ve ever eaten. I pass through Moorhead, a rundown town whose crossing of the Southern and Yazoo train lines was the subject of an early folk song heralding the birth of the blues. Further south, in Vicksburg, there’s Catfish Row, the southernmost end to the Mississippi Delta, where I find a famous tamale stand, and a quaint food stall that lifts the humble tomato to legendary status. Near the border, Natchez sits quiet and historic, with riverboats and casinos lining its shores and old Victorian homes overlooking the Mississippi River from its high bluffs, a few nice restaurants, and Smoot’s Grocery Blues Lounge offering respite and good tunes for the weary traveler. In Louisiana there are farmlands tended by a new generation at Bayou Sarah, keeping a different kind of history and legacy alive and bringing an age-old trade into the modern era. In Baton Rouge I find an intimate blues lounge and a restaurant specializing in sweet and savory pies, about as Southern as Southern gets. And finally in New Orleans, the city sweltering and swinging in its sultriness, Highway 61 comes to an end and the river makes one final bend and lends to the city one of its many aliases, The Crescent City. Here, an old club finds a new lease on life, cuisines once buried and white-washed re-emerge triumphantly, and one of the city’s oldest roads finds itself at the center of a thriving local community. At the end of my journey I return home and walk along the levee listening to the river, the air heavy and humid and ripe in this magical place, the mighty Mississippi still history’s trowel, those ancient mountains and forests borne on its currents to this land infinitely low and deep and sweet to decay and be reborn. This place I call home that now extends far beyond my childhood boundaries, out into the known and unknown worlds, all just a highway away.

This essay is part of The Great Escape, Atlas Obscura’s soon-to-launch guide to American road trips, featuring more custom itineraries, regional highlights, and practical tips for travelers hitting the road together. See where Aaron stopped.

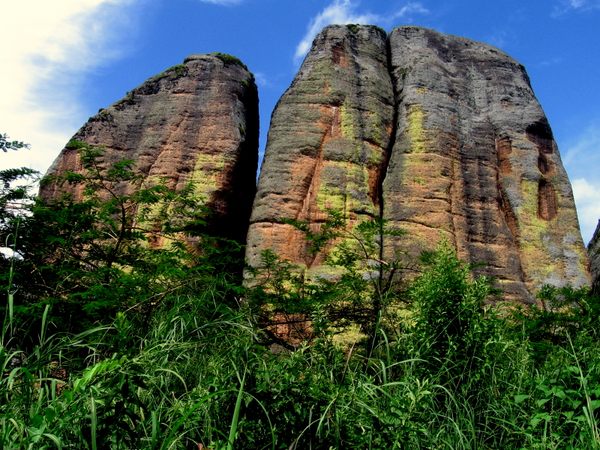

Highway 61 is known as “The Blues Highway” as it makes its way from New Orleans to Memphis, following the Mississippi River through lands forged over eons. From the coastal swamps of Louisiana to the alluvial plains of The Delta, the highway connects these landscapes to the human tales etched into the soil—telling the story of the Deep South through a journey of migration, transformation, and enduring spirit.

In New Orleans, where I was born and raised, Highway 61 was the end of my known world. It was a road of short-stay motels, pawn shops, bingo parlors, and a pervading sense of danger. It was the boundary of my childhood, of all that was safe and familiar. Years later, as an adult, I would come to know the highway as a conduit to the past, an artery of profound historical and cultural significance, invention and reinvention, of human dreams pinned to its asphalt, ever following the river like an acolyte to the great hand that carved both into the mythos of the South.

In Louisiana, the highway buckles and keeps time on car tires, skipping like scratches on old vinyl. Mississippi is its beating heart, where the blues was born, sung with lament and anger and hope in hollers, shouts, and chants. In Memphis, after the Great War and the Great Migration, the road brought blues music to the big stage, at home on Beale Street, where it dug in its heels and grew roots that couldn’t be plucked.

To drive along this highway is to make a pilgrimage through the South, its history and its legends. And so, because the river runs south and because all journeys are eventual homeward journeys, I begin my road trip in Memphis, the Delta’s spiritual, northernmost terminus.

After feasting on some of the region’s best soul food and barbecue, I leave Tennessee and cross the border into Mississippi, the land flat and low, all horizon, its cotton fields scorched under the midday sun and the tarred road shimmering with excess heat.

Past Tunica, barely an hour south of Memphis, the highway passes through Clarksdale—the epicenter of Delta blues music. Here is where Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil, and where Roger Stolle opened Cat Head Delta Blues & Folk Art to help revive interest in a dying town, where Red’s juke joint remains one of the last of a fading breed of original blues venues.

Onward the Delta stretches wide and thin between the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers. I stop in a famed family run pottery shop, and at Doe’s Eat Place I have some of the best steak I’ve ever eaten. I pass through Moorhead, a rundown town whose crossing of the Southern and Yazoo train lines was the subject of an early folk song heralding the birth of the blues.

Further south, in Vicksburg, there’s Catfish Row, the southernmost end to the Mississippi Delta, where I find a famous tamale stand, and a quaint food stall that lifts the humble tomato to legendary status.

Near the border, Natchez sits quiet and historic, with riverboats and casinos lining its shores and old Victorian homes overlooking the Mississippi River from its high bluffs, a few nice restaurants, and Smoot’s Grocery Blues Lounge offering respite and good tunes for the weary traveler.

In Louisiana there are farmlands tended by a new generation at Bayou Sarah, keeping a different kind of history and legacy alive and bringing an age-old trade into the modern era. In Baton Rouge I find an intimate blues lounge and a restaurant specializing in sweet and savory pies, about as Southern as Southern gets.

And finally in New Orleans, the city sweltering and swinging in its sultriness, Highway 61 comes to an end and the river makes one final bend and lends to the city one of its many aliases, The Crescent City. Here, an old club finds a new lease on life, cuisines once buried and white-washed re-emerge triumphantly, and one of the city’s oldest roads finds itself at the center of a thriving local community.

At the end of my journey I return home and walk along the levee listening to the river, the air heavy and humid and ripe in this magical place, the mighty Mississippi still history’s trowel, those ancient mountains and forests borne on its currents to this land infinitely low and deep and sweet to decay and be reborn. This place I call home that now extends far beyond my childhood boundaries, out into the known and unknown worlds, all just a highway away.

![nqz "I would be lying if I said I don't [feel pressure]. It was so different for me to see all those people and be in a Major playoffs"](https://img-cdn.hltv.org/gallerypicture/kAkShxXB96gCZmlpU-ivfH.jpg?auto=compress&ixlib=java-2.1.0&m=/m.png&mw=107&mx=20&my=474&q=75&w=800&s=935037b04cd96d3e70935ccfb24c348e#)