The Fantastic, Fading Retro Diners of Hong Kong

I traveled the breadth of Hong Kong Island not for sweet, Cantonese-style roast pork but rather for a slab of French toast. Specifically, one smeared with peanut butter before being deep-fried and drizzled with sweetened condensed milk. If this sounds distinctly un-Chinese, well it is—kind of. I was crossing Hong Kong to eat at cha chaan tengs, a genre of restaurant that plucks elements from both West and East, blending them into something uniquely local, often in a nostalgia-inducing package. “In the past, ice was difficult to get,” says Veronica Mak, a professor at Hong Kong Shue Yan University who has written about the history of Hong Kong’s cha chaan tengs. Over a cup of tea and toast drizzled with condensed milk, she traces the restaurants' origins back to bing sutts, or “ice shops,” that emerged in early 20th-century Hong Kong. These venues were known for serving cold drinks—at the time, a new and exciting luxury item. Mak says that bing sutts didn’t have a full kitchen, “just light food—tea, coffee, ice cream.” She explains that Hong Kong’s dual status as a port and a British colony meant that these meals often revolved around imported items such as black tea, coffee, tinned milk, wheat flour, dried pasta, and butter. After World War II, bing sutts began to serve more substantial meals, often incorporating Western cooking techniques and dishes such as baked items, breads, breakfast-style egg dishes, and sandwiches, ultimately morphing into what today are known as cha chaan tengs. “There’s certain non-negotiable menu items a cha chaan teng must have, such as lai cha, milk tea.” explains Janice Leung-Hayes, a food writer from Hong Kong. We’re chatting in her local cha chaan teng, an aged, lived-in space that blurs the line between residence and restaurant, and where orders, such as our eggy French toast with condensed milk, are still scratched out by hand. The Cantonese word for tea—cha—is right there in the genre’s name (Leung-Hayes explains that the phrase chaan teng denotes a Western-style restaurant). But in this case, it refers to black tea drunk with milk, a distinctly Western concept in China. Early cha chaan tengs boasted that their tea was filtered through silk stockings, and today the milk is still almost always poured from tins. Coffee is also common, as is yuenyeung or yin-yang, a drink that combines coffee and tea. Both Mak and Leung-Hayes argue that baked goods are another intrinsic element of the cha chaan teng. Baking is an imported cooking technique, but it didn’t take long for locals to develop their own repertoire of baked goods, the most celebrated example of which is the pineapple bun. “My dad, he cared about two things: baked goods, and coffee and tea,” says Donald Chan, the second-generation owner of Kam Wah Cafe, a cha chaan teng in Kowloon that is arguably Hong Kong’s most famous destination for pineapple buns. Named not for any fruity ingredient but rather for their caramelized, scored surface, pineapple buns have emerged as a cha chaan teng staple. The buns at Kam Wah are the size of a boxer’s fist with a barely sweet crumb and that distinctive topping, and are served with a thick pat of lemon-infused butter. Chan claims that Kam Wah bakes 5,000 per day, yet in-house bakeries such as his are now increasingly rare as industrial bakeries provide cha chaan tengs with baked goods. If cha chaan tengs have another staple ingredient, it’s the egg. Eggs are not unusual in Cantonese cuisine. But their Western preparations at cha chaan tengs—scrambled or fried and served as a centerpiece dish, or in the form of a sandwich—were a novelty to Hong Kongers. And perhaps nobody in Hong Kong does eggs better than Australia Dairy Company. I squeezed into a tight, 1970s-era booth illuminated by bright fluorescent lights and ordered the restaurant’s Breakfast Set, which included a small plate of scrambled eggs and toast, a bowl of macaroni soup, and a cup of milk tea. I’ve encountered my fair share of scrambled eggs, but these were revelatory: somehow existing in a state precisely between slightly undercooked and just-barely-set, with a pleasantly salty flavor, a golden hue, and none of the seepage—for lack of a better word—that often befalls home-scrambled eggs. Australia Dairy Company, which is exceedingly popular, is also infamous for yet another element of the cha chaan teng experience: quick, brusque (some might say rude) service. Solo diners will inevitably be seated with others, and one is expected to order, eat, and pay in quick succession—cha chaan tengs aren’t for lingering. As early cha chaan tengs began to expand their menus, they added noodle (especially instant noodles) and rice (often oven-baked) dishes; white-bread sandwiches; sweet snacks such as French toast; and macaroni, perhaps the most ubiquitous (and divisive) cha chaan teng menu item. The pasta is served as a soup, which is typically topped with some form of protein—slices of ham or char siu, minced bee

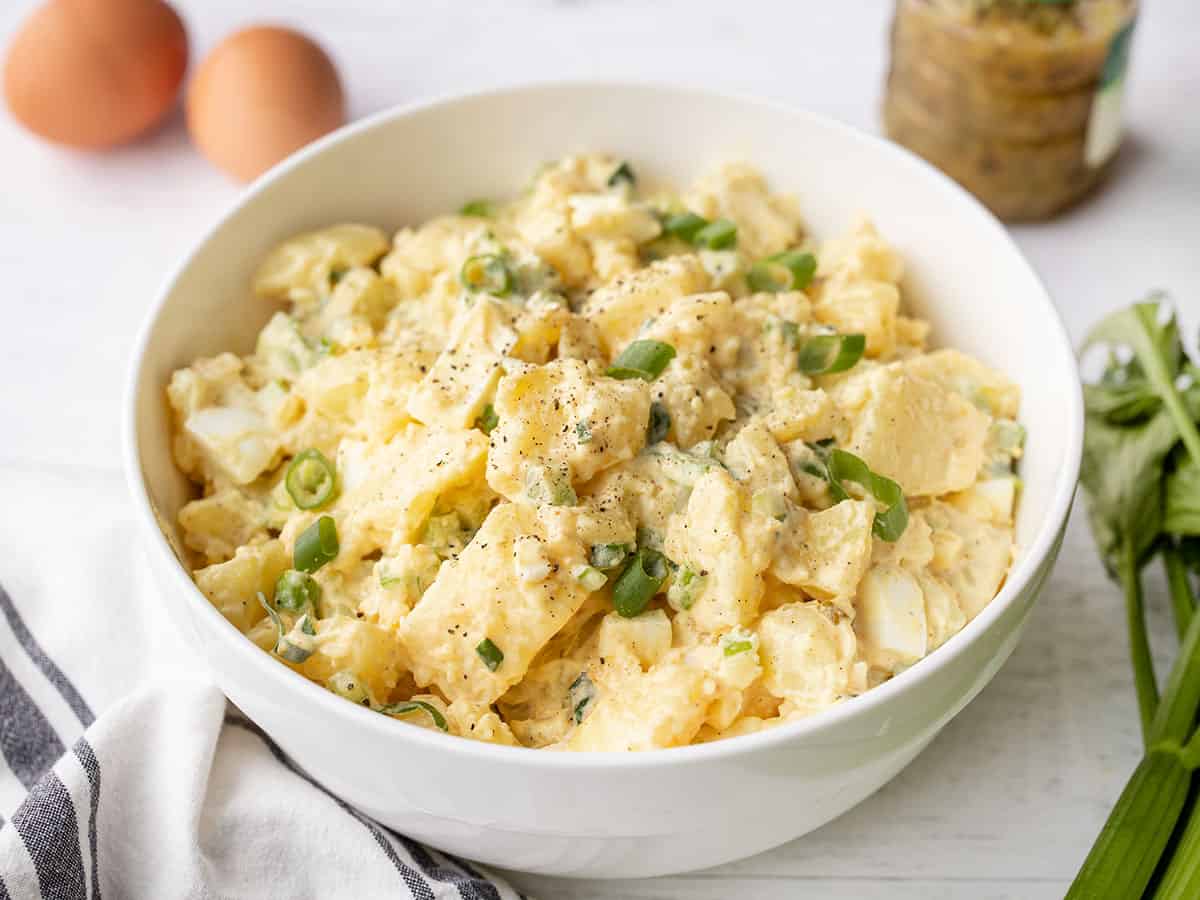

I traveled the breadth of Hong Kong Island not for sweet, Cantonese-style roast pork but rather for a slab of French toast. Specifically, one smeared with peanut butter before being deep-fried and drizzled with sweetened condensed milk.

If this sounds distinctly un-Chinese, well it is—kind of. I was crossing Hong Kong to eat at cha chaan tengs, a genre of restaurant that plucks elements from both West and East, blending them into something uniquely local, often in a nostalgia-inducing package.

“In the past, ice was difficult to get,” says Veronica Mak, a professor at Hong Kong Shue Yan University who has written about the history of Hong Kong’s cha chaan tengs. Over a cup of tea and toast drizzled with condensed milk, she traces the restaurants' origins back to bing sutts, or “ice shops,” that emerged in early 20th-century Hong Kong. These venues were known for serving cold drinks—at the time, a new and exciting luxury item.

Mak says that bing sutts didn’t have a full kitchen, “just light food—tea, coffee, ice cream.” She explains that Hong Kong’s dual status as a port and a British colony meant that these meals often revolved around imported items such as black tea, coffee, tinned milk, wheat flour, dried pasta, and butter. After World War II, bing sutts began to serve more substantial meals, often incorporating Western cooking techniques and dishes such as baked items, breads, breakfast-style egg dishes, and sandwiches, ultimately morphing into what today are known as cha chaan tengs.

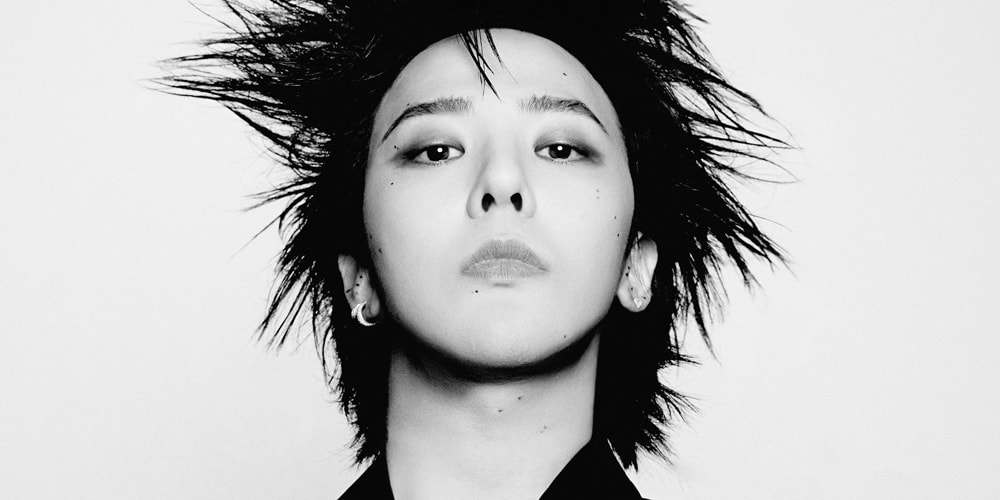

“There’s certain non-negotiable menu items a cha chaan teng must have, such as lai cha, milk tea.” explains Janice Leung-Hayes, a food writer from Hong Kong. We’re chatting in her local cha chaan teng, an aged, lived-in space that blurs the line between residence and restaurant, and where orders, such as our eggy French toast with condensed milk, are still scratched out by hand.

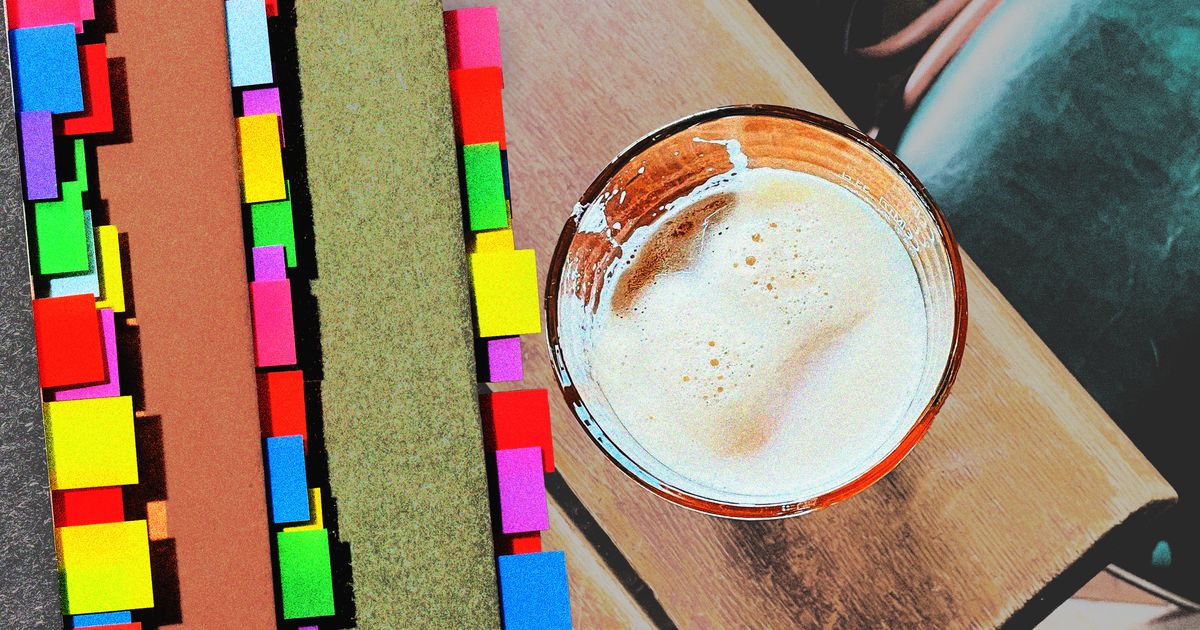

The Cantonese word for tea—cha—is right there in the genre’s name (Leung-Hayes explains that the phrase chaan teng denotes a Western-style restaurant). But in this case, it refers to black tea drunk with milk, a distinctly Western concept in China. Early cha chaan tengs boasted that their tea was filtered through silk stockings, and today the milk is still almost always poured from tins. Coffee is also common, as is yuenyeung or yin-yang, a drink that combines coffee and tea.

Both Mak and Leung-Hayes argue that baked goods are another intrinsic element of the cha chaan teng. Baking is an imported cooking technique, but it didn’t take long for locals to develop their own repertoire of baked goods, the most celebrated example of which is the pineapple bun.

“My dad, he cared about two things: baked goods, and coffee and tea,” says Donald Chan, the second-generation owner of Kam Wah Cafe, a cha chaan teng in Kowloon that is arguably Hong Kong’s most famous destination for pineapple buns. Named not for any fruity ingredient but rather for their caramelized, scored surface, pineapple buns have emerged as a cha chaan teng staple. The buns at Kam Wah are the size of a boxer’s fist with a barely sweet crumb and that distinctive topping, and are served with a thick pat of lemon-infused butter. Chan claims that Kam Wah bakes 5,000 per day, yet in-house bakeries such as his are now increasingly rare as industrial bakeries provide cha chaan tengs with baked goods.

If cha chaan tengs have another staple ingredient, it’s the egg. Eggs are not unusual in Cantonese cuisine. But their Western preparations at cha chaan tengs—scrambled or fried and served as a centerpiece dish, or in the form of a sandwich—were a novelty to Hong Kongers. And perhaps nobody in Hong Kong does eggs better than Australia Dairy Company.

I squeezed into a tight, 1970s-era booth illuminated by bright fluorescent lights and ordered the restaurant’s Breakfast Set, which included a small plate of scrambled eggs and toast, a bowl of macaroni soup, and a cup of milk tea. I’ve encountered my fair share of scrambled eggs, but these were revelatory: somehow existing in a state precisely between slightly undercooked and just-barely-set, with a pleasantly salty flavor, a golden hue, and none of the seepage—for lack of a better word—that often befalls home-scrambled eggs.

Australia Dairy Company, which is exceedingly popular, is also infamous for yet another element of the cha chaan teng experience: quick, brusque (some might say rude) service. Solo diners will inevitably be seated with others, and one is expected to order, eat, and pay in quick succession—cha chaan tengs aren’t for lingering.

As early cha chaan tengs began to expand their menus, they added noodle (especially instant noodles) and rice (often oven-baked) dishes; white-bread sandwiches; sweet snacks such as French toast; and macaroni, perhaps the most ubiquitous (and divisive) cha chaan teng menu item. The pasta is served as a soup, which is typically topped with some form of protein—slices of ham or char siu, minced beef, a fried egg. “That’s a hallmark of all cha chaan teng food,” says Leung-Hayes, the food writer. “It’s very processed and very carby.”

Today, cha chaan tengs can still be found across Hong Kong, but they face intense competition from contemporary coffee shops and international fast-food concepts also offering a cheap, quick meal. “For younger, university-age kids, there’s so much choice now,” Leung-Hayes explains. “They don’t need to go to cha chaan tengs. When I was in uni or high school, it was the default.”

In particular, the independently owned cha chaan teng is a dying breed, hit especially hard by the pandemic and skyrocketing rents. They’re also being pushed out by brands with more contemporary interiors and longer, more progressive menus. Yet even these have suffered in recent years, with Tsui Wah, the territory’s largest chain, having contracted from 30 branches in 2018 to eight at press time.

But cha chaan tengs continue to roll with the times and blur the lines between cuisines. At Ngan Lung, a nearly 60-year-old cha chaa teng in the fishing village of Lei Yue Mun, the menu includes upscale items such as abalone and a dish best translated as “egg-white bean curd French toast.” At Hoi Chiu Canteen, in Kowloon, the forward-thinking chef has tweaked the otherwise beige and bland macaroni soup into a spicy dry-fry drizzled with chili and scallion oil. Also in Kowloon, the ambitious young couple behind Tai On Coffee & Tea Shop took over a legacy cha chaan teng and introduced items such as milk tea-flavored egg tarts. And at Sleepyhead, on Hong Kong Island, the milk tea is poured not through silk stockings but rather from a nitro tap.

And although they didn’t necessarily grow up with them, in recent years, Hong Kong’s youth have increasingly been drawn to cha chaan tengs. “Young people don’t have a personal collective memory of cha chaan tengs in the ’80s and ’90s,” says the academic, Veronica Mak. Yet, she explains, disillusioned by increased surveillance, arrests, and harsh security measures imposed by China after a series of pro-democracy protests in 2019—the most extensive in the territory’s history—some young Hongkongers have expressed nostalgia for the era of colonial rule. This, she claims, has led to a resurgence of interest in the territory’s classic cha chaan tengs, as well as a spate of new Instagram-friendly cha chaan teng openings, complete with faux-retro interior design elements.

“Cha chaan tengs are found only in Hong Kong, not even in Guangdong,” says the food writer Leung-Hayes, referencing Hong Kong’s mainland neighbor. “It’s ours—it’s become our culture—it’s our thing.”

Explore more of the world’s culinary wonders with Gastro Obscura’s second annual Feast, a series of guides, stories, and recipes from our top six dining destinations of the year.

.jpg)