What I Found Driving Through Appalachia

This essay is part of The Great Escape, Atlas Obscura’s soon-to-launch guide to American road trips, featuring more custom itineraries, regional highlights, and practical tips for travelers hitting the road together. See where Mason stopped. The world still doesn’t quite know what to make of Appalachia. The mountainous, multi-state region has long been defined both by mystery and misconceptions. In many ways, it’s been America’s shadow since the nation’s birth. Early settlers fretted about Native-American tribes, dark hollows, and looming wilderness in the 1600s and 1700s, while modern folks tend to worry more about environmental degradation and concentrations of Trump voters. Yet, Appalachia is much like America as a whole—it sprawls from south to north across several states, spawning local cultures marked as much by their diversity and differences as what they have in common. And these mountains are old. Rocks formed during the Precambrian era have been found in some places. Parts of the Appalachian Mountains are thought to be even older than Saturn’s rings, and millennia of erosion have given rise to one of the richest temperate ecosystems in the world. This diverse bioregion has become home to a melting pot of culture. Archaeological findings indicate that Native-American tribes inhabited the region 20,000 years ago. The first Europeans arrived in the 1500s, when Spanish conquistadors ventured up from what is now Florida. English and French settlers followed, establishing a general pattern that continues into the present: Newcomers bring their cultural traditions into the region, where they are absorbed into the greater whole. That’s why any portrait of Appalachia as a white monoculture is false. Mountain communities are surprisingly diverse, incorporating individuals from a wide variety of ethnic, racial, and sociocultural backgrounds. The coal boom that gripped Appalachia beginning in the 1800s attracted people to the mountains in search of jobs. Coal companies famously recruited Black Americans and Italian and Eastern European immigrants along with white workers to keep them divided by race and language. The attempt backfired when labor organizers began making inroads—perhaps most famously depicted in John Sayles’ 1987 film Matewan in a scene in which white guitar and fiddle players jam in a coal camp with an Italian mandolin player and a Black blues harp player. That mix of influences distinguishes Appalachian culture, making it a particularly appealing destination for travelers in search of memorable places and experiences. Yet Appalachia can be intimidating for visitors. Its densely packed mountains, preponderance of deep hollows and steep, twisty roads can seem impenetrable. Plus, few regions have been more deeply mythologized, mischaracterized, and maligned in the popular imagination. After the Civil War, local-color writers visited the mountains and wrote stories for Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s Magazine, and other publications that depicted the region as an isolated place out of time, populated by backwards people with exaggerated accents. These writers established the hillbilly stereotype that clings to Appalachia still today. The local-color writers whitewashed the people of the Appalachian Mountains as a racially monolithic populace that preserved an otherwise lost Scots-Irish culture. English, Irish, and Scottish influences are indeed present in Appalachian culture, but they mingle with elements from Africa, southern and eastern Europe, the Middle East, the Indian sub-continent, and many others. Take bluegrass and old-time music. String-band music is considered a central component of Appalachia’s culture, but it consists of bits and pieces taken from the rest of the world. Melodies and lyrics are drawn from English and Scottish ballads that are hundreds of years old, and blended with the banjo's African roots and syncopated rhythms. That blend of culture and Appalachia’s geography make it a microcosm of American history. Its location proximate to the East Coast made Appalachia the United States’ first frontier. These mountains were where George Washington first became a military leader. They were the site of broken treaties and the early American Republic’s first major removal of Native people, as well as early rebellions that prompted the Constitutional Convention. During the Civil War, West Virginia was violently severed from Virginia to become its own state, and the war’s guerrilla battles in the mountains left some communities divided for decades. The post-war African-American diaspora from the Deep South passed largely through Appalachia and established Black communities throughout the region, especially in job-heavy industrial hubs. Voracious capitalists also moved in, clearing the land of its timber and digging for coal. Unions moved in to organize the mines, leading to escalating violence that culminated in the Battle of Blair Mountain—the nation’s largest armed insurge

This essay is part of The Great Escape, Atlas Obscura’s soon-to-launch guide to American road trips, featuring more custom itineraries, regional highlights, and practical tips for travelers hitting the road together. See where Mason stopped.

The world still doesn’t quite know what to make of Appalachia. The mountainous, multi-state region has long been defined both by mystery and misconceptions. In many ways, it’s been America’s shadow since the nation’s birth. Early settlers fretted about Native-American tribes, dark hollows, and looming wilderness in the 1600s and 1700s, while modern folks tend to worry more about environmental degradation and concentrations of Trump voters.

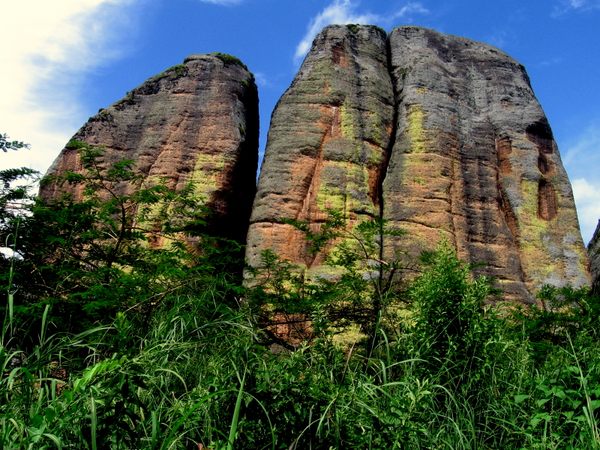

Yet, Appalachia is much like America as a whole—it sprawls from south to north across several states, spawning local cultures marked as much by their diversity and differences as what they have in common. And these mountains are old. Rocks formed during the Precambrian era have been found in some places. Parts of the Appalachian Mountains are thought to be even older than Saturn’s rings, and millennia of erosion have given rise to one of the richest temperate ecosystems in the world.

This diverse bioregion has become home to a melting pot of culture. Archaeological findings indicate that Native-American tribes inhabited the region 20,000 years ago. The first Europeans arrived in the 1500s, when Spanish conquistadors ventured up from what is now Florida. English and French settlers followed, establishing a general pattern that continues into the present: Newcomers bring their cultural traditions into the region, where they are absorbed into the greater whole. That’s why any portrait of Appalachia as a white monoculture is false. Mountain communities are surprisingly diverse, incorporating individuals from a wide variety of ethnic, racial, and sociocultural backgrounds.

The coal boom that gripped Appalachia beginning in the 1800s attracted people to the mountains in search of jobs. Coal companies famously recruited Black Americans and Italian and Eastern European immigrants along with white workers to keep them divided by race and language. The attempt backfired when labor organizers began making inroads—perhaps most famously depicted in John Sayles’ 1987 film Matewan in a scene in which white guitar and fiddle players jam in a coal camp with an Italian mandolin player and a Black blues harp player.

That mix of influences distinguishes Appalachian culture, making it a particularly appealing destination for travelers in search of memorable places and experiences. Yet Appalachia can be intimidating for visitors. Its densely packed mountains, preponderance of deep hollows and steep, twisty roads can seem impenetrable. Plus, few regions have been more deeply mythologized, mischaracterized, and maligned in the popular imagination.

After the Civil War, local-color writers visited the mountains and wrote stories for Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s Magazine, and other publications that depicted the region as an isolated place out of time, populated by backwards people with exaggerated accents. These writers established the hillbilly stereotype that clings to Appalachia still today.

The local-color writers whitewashed the people of the Appalachian Mountains as a racially monolithic populace that preserved an otherwise lost Scots-Irish culture. English, Irish, and Scottish influences are indeed present in Appalachian culture, but they mingle with elements from Africa, southern and eastern Europe, the Middle East, the Indian sub-continent, and many others.

Take bluegrass and old-time music. String-band music is considered a central component of Appalachia’s culture, but it consists of bits and pieces taken from the rest of the world. Melodies and lyrics are drawn from English and Scottish ballads that are hundreds of years old, and blended with the banjo's African roots and syncopated rhythms.

That blend of culture and Appalachia’s geography make it a microcosm of American history. Its location proximate to the East Coast made Appalachia the United States’ first frontier. These mountains were where George Washington first became a military leader. They were the site of broken treaties and the early American Republic’s first major removal of Native people, as well as early rebellions that prompted the Constitutional Convention.

During the Civil War, West Virginia was violently severed from Virginia to become its own state, and the war’s guerrilla battles in the mountains left some communities divided for decades. The post-war African-American diaspora from the Deep South passed largely through Appalachia and established Black communities throughout the region, especially in job-heavy industrial hubs. Voracious capitalists also moved in, clearing the land of its timber and digging for coal. Unions moved in to organize the mines, leading to escalating violence that culminated in the Battle of Blair Mountain—the nation’s largest armed insurgency since the Civil War.

In the 1960s, Appalachia was stereotyped in national media again, this time in stark, black-and-white photos that were published in the years after President Lyndon Johnson declared a “war on poverty.” Added to the pre-existing “hillbilly” stereotype, these images entrenched a national image of Appalachia as a misbegotten part of the country. That's the frame many people still bring to the mountains. But if that's your image of Appalachia, prepare yourself for a Wizard of Oz moment when the mountains explode into living color.

Appalachia isn’t just a microcosm of American history. It offers a glimpse into its future too. In his forward to Appalachia: A History, historian John Alexander Williams lays out his case for why the region illustrates a model for surviving global market capitalism.

“For much of the century, official attention turned on the question of why and how the region failed to keep pace with the material growth of an urbanized consumer society, but at the beginning of the 21st century it is reasonable to ask whether Appalachia may have led the nation, not lagged behind, into a future whose outline is only just now coming into view,” Williams writes. The “combination of exploitation and per-/re-sistance, of crisis and renewal, that Appalachian history manifests may turn out to be instructive to every dweller in the postmodern world.”

The Appalachia of today encompasses all that history and its wide-ranging influences, in an ever-changing cultural landscape that never stops evolving. To truly understand, one must live here. But despite that and centuries of industrial extraction, a winding road trip will give you a taste of the riches Appalachia still holds.

![nqz "I would be lying if I said I don't [feel pressure]. It was so different for me to see all those people and be in a Major playoffs"](https://img-cdn.hltv.org/gallerypicture/kAkShxXB96gCZmlpU-ivfH.jpg?auto=compress&ixlib=java-2.1.0&m=/m.png&mw=107&mx=20&my=474&q=75&w=800&s=935037b04cd96d3e70935ccfb24c348e#)