Batman Forever at 30: How the Val Kilmer Sequel Was as Much a Studio Recalibration as a Fresh New Take on the Dark Knight

Three decades after its release, Val Kilmer and Joel Schumacher's Batman Forever remains a stylistic detour that dared to show Gotham in a different light. Literally.

By the early 1990s, Gotham City was a place at a crossroads — not just on the comics page, but on the silver screen. The runaway success of 1989’s Batman had turned DC Comics’ brooding Dark Knight into a global pop-culture juggernaut. But 1992’s darker, more off-kilter follow-up, Batman Returns, presented a challenge the suits at Warner Bros. couldn’t ignore.

Director Tim Burton’s gothic stylings and psychological undertones gave the films a distinct flavor far removed from traditional superhero fare. But Returns’ darker, more adult themes and its sinister villains — Danny DeVito’s grotesque Penguin and Michelle Pfeiffer’s complex, troubled Catwoman — also alienated parents and retailers alike with its unapologetically weird, adult-oriented tone.

While the sequel did solid business, its earnings still marked a sizable drop from the earlier film, with Burton’s unfiltered approach proving especially divisive. Warner Bros. suddenly found itself wrestling with a dilemma: how to keep their new golden goose of a franchise afloat in a market hungry for spectacle, cross-quadrant appeal, and yes, merchandising galore.

That delicate balancing act would shape the creation of the third film, Batman Forever. As the film celebrates its 30th anniversary this week, let’s take a look at the fascinating cinematic time capsule it has come to be in the years since.

A Gotham City in Transition

With concerned parents threatening boycotts and Happy Meal tie-ins in peril, Warner Bros. decided a tonal course correction was in order. Burton, who had given the franchise its visual signature, was nudged into a producer role (his name still prominent in the opening credits, perhaps as a gesture of reassurance, albeit with minimal input and likely under duress). While Burton had been developing a third installment centered around the Scarecrow, the studio increasingly saw his idiosyncratic sensibilities as misaligned with their evolving goals.

In came Joel Schumacher, a director with a résumé as eclectic as it was stylish, who came in only after first getting assurance from Burton himself that he was okay with stepping aside. From The Lost Boys to Falling Down, Schumacher had proven he could deliver visual pop and thematic heft. His Gotham would be less shadow-drenched nightmare, more neon-drenched fever dream — a city of kinetic color and electric energy.

But this wasn’t just about lighting changes and brighter spandex. It signaled a broader pivot: Batman as brand. Theatrical, toyetic, and teed up for mass consumption. Schumacher, for all the neon and noise, did try to delve a bit deeper under Bruce Wayne’s cowl. However, his hiring marked the moment commerce began to drive the creative engine more visibly than ever before.

Initial scripting duties went to Lee and Janet Scott Batchler, who delivered a draft heavy on psychological texture. Too heavy, as far as the studio was concerned. Enter Akiva Goldsman, who reshaped the narrative into something faster and splashier, cutting down on introspection in favor of momentum. Not quite as campy as the 1960s TV show (that was still two years away), but certainly closer than the Burton films had been.

Even the score got a tonal revamp. Danny Elfman’s haunting, operatic themes (also utilized in the fan-fave Batman: The Animated Series) gave way to Elliot Goldenthal’s wild, brassy compositions — less brooding and more bombastic, in lockstep with Schumacher’s amplified aesthetic. (The theme does grow on you, it’s worth acknowledging.)

Val Kilmer Dons the Cape and Cowl

Casting choices further reflected this tonal recalibration. Michael Keaton, who overcame initial fan skepticism and quickly became beloved as Bruce Wayne and Batman, declined to return. Offered a hefty $15 million paycheck, he still walked away, citing discomfort with the new direction and loyalty to Burton’s vision.

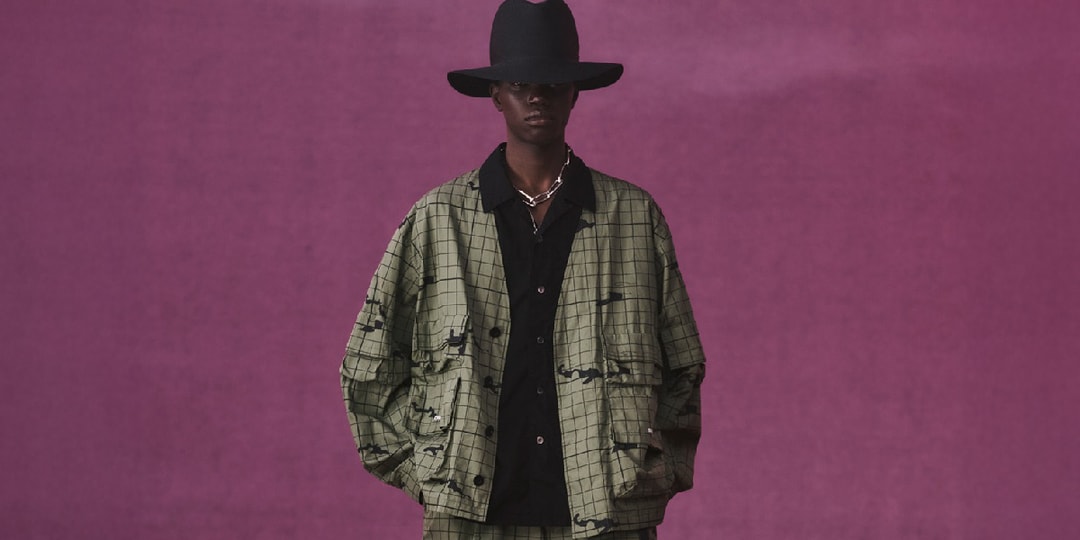

Although a roster of mid-’90s heartthrobs were considered, it was Val Kilmer, fresh off his iconic turn as Doc Holliday in Tombstone, who stepped up, signing on to wear the cape without even reading a script. His take on Bruce Wayne was cooler and more reserved — bordering on sleepy in some scenes — but there’s no doubt he cut a dashing figure in the sculpted rubber suit.

As for the villains, Warner Bros. leaned hard into marquee names, just as they had previously. Recent Academy Award winner Tommy Lee Jones, who had just worked with Schumacher on The Client, took over from Billy Dee Williams as District Attorney Harvey Dent/Two-Face. (Williams would eventually get his due — in LEGO form, no less — in 2017.)

The Riddler was a more contentious casting journey. Robin Williams passed, Michael Jackson lobbied, but Jim Carrey — riding high from his 1994 Triple Crown of Ace Ventura, The Mask, and Dumb & Dumber — won out. His manic energy matched the movie’s madcap carnival vibe, though not everyone was thrilled. His performance became the film’s tonal bellwether: delightfully unhinged to some, gratingly over-the-top to others (including, most notably, Tommy Lee Jones).

Meanwhile, Nicole Kidman was brought in as the female lead, psychologist Dr. Chase Meridian, after Rene Russo — considered for the part when Keaton was still in the mix — was infuriatingly deemed too old, at 41, to play the 36-year-old Kilmer’s love interest. Regardless, the smoldering Kidman no doubt brought sex appeal and star power to the project while aligning with the slicker, more commercial direction favored by the studio.

Robin finally made his long-awaited entrance to the franchise as well, with Scent of a Woman’s Chris O’Donnell beating out the likes of Leonardo DiCaprio and Matt Damon to play Dick Grayson — reimagined as a rebellious teen (played by a 25-year-old) with an affinity for earrings, motorcycles, and just enough edge to seem cool in the MTV ’90s.

Notably, Michael Gough and Pat Hingle returned as Alfred and Commissioner Gordon, essentially the “Q” and “M” of this series, offering a tenuous thread of continuity to the prior entries and giving Forever just enough connective tissue to avoid being thought of as a hard reboot. (That wouldn’t come until Batman Begins 10 years later.)

A Rave in Comic Book Form

Gotham City itself got a makeover as well, courtesy of production designer Barbara Ling, who jettisoned the expressionist grime of Anton Furst’s earlier work in favor of towering statues, neon lighting, and architectural excess. It wasn’t just stylized, it was maximalist, looking less like a city and more like a rave rendered in comic book form.

The Batsuit was also redesigned with a high-gloss finish and sculpted nipples — a detail that became a lightning rod for criticism but perfectly captured the film’s unapologetic shift toward camp. Even the Batmobile was reimagined, glowing with bio-mechanical flourishes that recalled H.R. Giger. Every production element leaned into what toy marketers call “play value.” From costumes to set pieces, it was all designed with dual functions: cinematic storytelling and shelf appeal.

Behind the scenes, not all was harmonious. Kilmer repeatedly clashed with Schumacher, who got into a shoving match at one point with the actor, and Carrey later recounted Jones telling him, memorably: “I cannot sanction your buffoonery.”

Still, the real battleground emerged in post-production. Warner Bros. pushed for a faster, lighter cut, leading to the removal of numerous scenes, including Bruce’s encounter with a giant bat and more psychological explorations. What remained was a polished, popcorn-friendly version that smoothed out rougher edges in favor of commercial considerations.

Release and Reappraisal

When Batman Forever hit theaters on June 16, 1995, its arrival was trumpeted with all the subtlety of the Bat-Signal, blasting across every TV screen, cereal box, and fast-food wrapper in sight. The marketing machine was in full tilt, and audiences responded in kind. Opening to a then-record $53 million, the film eventually pulled in over $330 million worldwide — handily outpacing Batman Returns and validating Warner Bros.’ gamble (at least in the short term).

Critics were more mixed, however. Some praised its energy and visual dazzle; others bemoaned the tonal whiplash and cartoonish villains. Fans, too, were divided. Younger viewers embraced the spectacle, while longtime Bat-faithful mourned the departure from the character’s darker, more introspective roots.

Batman Forever has undergone something of a reputational rebalancing since it first hit theaters. Initially greeted with open arms by audiences riding high on Bat-mania, it eventually found itself unfairly tethered to the neon excesses of its successor, 1997’s Batman & Robin, and dismissed as part of the franchise’s descent into self-parody. But with time and distance, a reassessment has taken root.

Viewed through a more generous lens, Forever reveals itself as a sincere (if uneven) effort to thread the needle between Tim Burton’s gothic melancholy and the toyetic sensibilities of a blockbuster-hungry studio. It doesn’t always stick the landing, but there’s a genuine ambition beneath the spectacle that makes it more than just a prelude to disaster.

Schumacher’s passing in 2020 and Kilmer’s a few months ago have further softened views on the film. Kilmer, who decided against returning for the sequel in favor of Paramount’s The Saint, summed up his sole time wearing the scalloped cape with a mix of wistfulness and wariness in his 2020 autobiography: “You gotta hand it to Batman. He’s far greater than any actor attempting to play him.”

A Lasting Impact

What becomes clear with 30 years of perspective is that while Batman Forever may not be the definitive Batman entry, it nonetheless remains a unique chapter in the Dark Knight’s cinematic history — a stylistic detour that dared to show Gotham in a different light. Literally.

Compared to the later interpretations by Christopher Nolan and Matt Reeves, Schumacher’s vision for Forever stands apart. Where Nolan and Reeves gave us grit and gravitas, Schumacher delivered glowsticks and Grand Guignol. And in doing so, he reminded us that Batman isn’t one thing. He’s whatever the culture (and the market) needs him to be.

This was no mere sequel, it was a studio recalibration masquerading as a movie. A brighter Batman, a less tortured Bruce Wayne, and a Gotham City awash in strobe lights instead of shadows. Whether it’s a triumph or a misstep may depend on your Batman of choice, but one thing’s for sure: Forever wasn’t just a title. It was a promise.