How Elise Wortley Climbed Mont Blanc in 1830s Women’s Attire

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. Dylan Thuras: Can you describe your favorite historical wardrobe that you have ever worn on one of your trips? Elise Wortley: Oh yeah, easily. It would be the Mont Blanc trip that I did, actually, last year. I wore this outfit that the same woman wore in 1838 when she climbed Mont Blanc. She was the first woman to climb the mountain. And outdoor clothes for women didn’t exist back then. So, she created this entire outfit herself. I mean, it was quite something. Massive wool dress with trousers underneath, all made of Scottish tweed with a huge bonnet. So, that’s probably my favorite outfit. Dylan: That must have weighed a ton. Like, all like wool heavy material, yeah? Elise: Yeah, it’s super heavy. Even in her book, she said hers weighed about 12 kilograms. That’s on top of everything else. So, yeah, it’s super heavy wool, really heavy. Dylan: Second question, also silly. What’s your most hated wardrobe piece that you’ve had to wear for one of these trips? Elise: Oh, the boots, probably. I’ve worn the same boots for a few of them now. And they’re hobnail boots that were quite the thing sort of in the 1800s and early 1900s. They’d nail nails, essentially, into the bottom of their boots for grip—which I say with inverted commas, they’re not that grippy. I’m Dylan Thuras, and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Today, we are talking with adventurer Elise Wortley. This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. Dylan: Elise recreates the journeys of legendary female explorers like Freya Stark or Alexandra David-Néel. She does it all with no modern gear, no shortcuts, no guarantees that it’s going to work out. She is wearing the same hobnail boots that they wore. And she recreates these journeys, not just to understand where they went, but what it felt like, what they endured, what she would need to endure to make it through these trips. And because of this, she has learned a lot about herself as well. Let’s go back before all of this begins. Let’s go back to your 20s. You’ve got, like, an art degree. If I understand correctly, you were working in PR. And things start to kind of maybe, like, unravel a little bit. Maybe you can just talk to me about this period in your life and what’s going on. Elise: Yeah, definitely. When I was about 20, I sort of started getting really bad panic attacks. It’s something I’m kind of really open about now. But mine was so bad that they turned into something that’s called general anxiety disorder. I basically felt like I was having a panic attack all day, every day. And this kind of went on for years and years. And obviously, it really took its toll. And I had to stop going to work and found it really hard to kind of do anything. And so that was a really kind of long process to try and get myself better. I had therapy, but I also went on medication, which I’m still on today and still kind of working through. So yeah, I just had this really unexpected, difficult time, which went on probably till I was about 26, 27, like quite badly. And yeah, that’s when I kind of started this project around that time when I started to feel a little bit better off the back of a little wild dream I had when I was younger. Dylan: Yeah, it sounds like you’re having this kind of intense anxiety, but it sounds like somewhere on this process, there’s something else going on too. You maybe find a book that you had had as a kid, or you sort of rediscover this thing that you had once loved? Elise: Yeah, that’s exactly it. I read this book by Alexandra David-Néel, and she has an incredible story. She left Europe in 1910, went off on this 14-year journey across Asia. She was the first Western woman to meet the Dalai Lama. She learnt Tibetan. She lived in a cave for two years in the freezing Himalayas, learning stomach breathing. She was just fascinated with Buddhism. And she went on this really long journey of trying to get into Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, to learn more about Buddhism. Because obviously, it’s not like now when you can just Google it. There’s like—they didn’t have anything. And I just read this story. And there were times in it where she spent the night on freezing mountain passes, like just in the snow. And I was just thinking like, how did she do this? And also, why don’t I know about her? Like, why was I ever taught about her at school? So, I just always had this little idea that I wanted to follow in her footsteps because nobody I spoke to had ever heard of her. I kind of wanted to raise her story, but also just find out how she did it back then, and how it might have felt for her. Because actually, in their writing, these women never really write about their feelings, because they were

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Dylan Thuras: Can you describe your favorite historical wardrobe that you have ever worn on one of your trips?

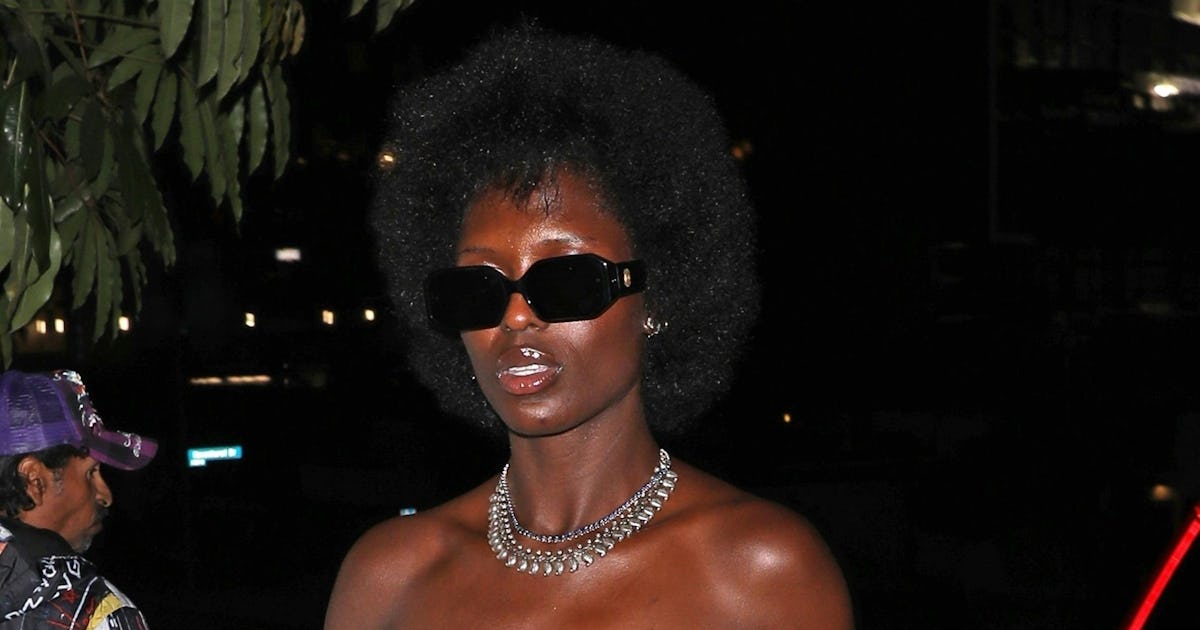

Elise Wortley: Oh yeah, easily. It would be the Mont Blanc trip that I did, actually, last year. I wore this outfit that the same woman wore in 1838 when she climbed Mont Blanc. She was the first woman to climb the mountain. And outdoor clothes for women didn’t exist back then. So, she created this entire outfit herself. I mean, it was quite something. Massive wool dress with trousers underneath, all made of Scottish tweed with a huge bonnet. So, that’s probably my favorite outfit.

Dylan: That must have weighed a ton. Like, all like wool heavy material, yeah?

Elise: Yeah, it’s super heavy. Even in her book, she said hers weighed about 12 kilograms. That’s on top of everything else. So, yeah, it’s super heavy wool, really heavy.

Dylan: Second question, also silly. What’s your most hated wardrobe piece that you’ve had to wear for one of these trips?

Elise: Oh, the boots, probably. I’ve worn the same boots for a few of them now. And they’re hobnail boots that were quite the thing sort of in the 1800s and early 1900s. They’d nail nails, essentially, into the bottom of their boots for grip—which I say with inverted commas, they’re not that grippy.

I’m Dylan Thuras, and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Today, we are talking with adventurer Elise Wortley.

This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Dylan: Elise recreates the journeys of legendary female explorers like Freya Stark or Alexandra David-Néel. She does it all with no modern gear, no shortcuts, no guarantees that it’s going to work out. She is wearing the same hobnail boots that they wore. And she recreates these journeys, not just to understand where they went, but what it felt like, what they endured, what she would need to endure to make it through these trips. And because of this, she has learned a lot about herself as well. Let’s go back before all of this begins. Let’s go back to your 20s. You’ve got, like, an art degree. If I understand correctly, you were working in PR. And things start to kind of maybe, like, unravel a little bit. Maybe you can just talk to me about this period in your life and what’s going on.

Elise: Yeah, definitely. When I was about 20, I sort of started getting really bad panic attacks. It’s something I’m kind of really open about now. But mine was so bad that they turned into something that’s called general anxiety disorder. I basically felt like I was having a panic attack all day, every day. And this kind of went on for years and years. And obviously, it really took its toll. And I had to stop going to work and found it really hard to kind of do anything. And so that was a really kind of long process to try and get myself better. I had therapy, but I also went on medication, which I’m still on today and still kind of working through. So yeah, I just had this really unexpected, difficult time, which went on probably till I was about 26, 27, like quite badly. And yeah, that’s when I kind of started this project around that time when I started to feel a little bit better off the back of a little wild dream I had when I was younger.

Dylan: Yeah, it sounds like you’re having this kind of intense anxiety, but it sounds like somewhere on this process, there’s something else going on too. You maybe find a book that you had had as a kid, or you sort of rediscover this thing that you had once loved?

Elise: Yeah, that’s exactly it. I read this book by Alexandra David-Néel, and she has an incredible story. She left Europe in 1910, went off on this 14-year journey across Asia. She was the first Western woman to meet the Dalai Lama. She learnt Tibetan. She lived in a cave for two years in the freezing Himalayas, learning stomach breathing. She was just fascinated with Buddhism. And she went on this really long journey of trying to get into Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, to learn more about Buddhism. Because obviously, it’s not like now when you can just Google it. There’s like—they didn’t have anything. And I just read this story. And there were times in it where she spent the night on freezing mountain passes, like just in the snow. And I was just thinking like, how did she do this? And also, why don’t I know about her? Like, why was I ever taught about her at school? So, I just always had this little idea that I wanted to follow in her footsteps because nobody I spoke to had ever heard of her. I kind of wanted to raise her story, but also just find out how she did it back then, and how it might have felt for her. Because actually, in their writing, these women never really write about their feelings, because they were kind of battling to be taken as seriously as the men. So yeah, I just wanted to find out a little bit more about it. And eventually, I just went off on this first adventure and did it.

Dylan: So, Alexander traveled for like 14 years. I assume you did not take 14 years off of work, or you would still be—

Elise: No, I wanted to. I’d still be there now. Oh, my God.

Dylan: Yeah, yeah. What was that first trip plan? Maybe you could just tell me what you had in mind.

Elise: Yeah, so I wanted to do the last bit of her journey where she gets into Lhasa. But actually today, like back then, it’s very cut off, that part of the world. And you can’t walk where you want or do what you want, you have to have an escort. And the bit of Tibet I wanted to go to wasn’t possible. So I decided, okay, I’ll start the very beginning of her 14-year journey. So it’s this bit of India called Sikkim. It’s Himalayan kingdom, like it sticks up right at the top of India. It was actually its own country, I think, till the ’70s. It still has a monarchy, and it’s just this incredible place. So she went there and she trekked all the way to the base camp of Mount Kanchenjunga. It’s the third highest mountain in the world. And it’s there that she got her first views of Tibet and just became obsessed with trying to get into this country. So we thought I’d go and do that. And yeah, following her footsteps there and try and get those same views, because I kind of figured that mountains wouldn’t change that much in sort of 100 years, so I could still get those same incredible views that she had. So that was the plan.

Dylan: How long was that trip going to be?

Elise: That was about a month.

Dylan: Okay. Yeah.

Elise: Yeah. To kind of do all the walking and visit all the places I wanted to visit. It was going to be about a month. So yeah, it was a big trip.

Dylan: It’s one thing to retrace the steps of a famous explorer. It’s a whole nother thing to kind of be like, I want to get as close to that experience as possible, which for you has included kind of finding gear that is kind of similar to what they would have worn at the time. Why did that feel important to you? Why was it important to kind of go the extra step beyond just like going where they went? You really wanted to feel the textiles they were feeling.

Elise: Yeah. And that’s the bit I actually had the most doubts over. I’d be there going, “Why am I doing this?” as I was sort of putting it all on. But I just knew I would never fully understand—like, the whole point of this first trip anyway, was to kind of demonstrate what she went through, how brave she was, and what it would have been like for a woman back then. You know, they always had everything else against society, you know—you’ve got fighting against all these other things. And then their clothing was yet another barrier. So, I just wanted to show, you know, what they would have actually experienced. And they were battling to be taken as seriously as the men, like they would never get their books published, they found it hard to get press coverage. So they’d never write, you know, like I was freezing cold, or my underwear was itching me or anything like that. So I just wanted to try and understand a bit more on a deeper level what they were going through. And I just knew I would never fully understand if I was in my puffy jacket and waterproof stuff.

Dylan: Yeah, yeah. And, you know, what were some of the most challenging parts of that first journey?

Elise: Yeah, I think, well, firstly, the cold, but also it was learning about the clothing. And funnily enough, wool is actually really, really warm. It’s so warm, but to the point where it’s too much sometimes. You get so hot and you’re sweating, and then it’s itching. But actually, it’s not that easy to unlayer because then what do you do with it, you have to carry it. So then you’re like, well, it’s easier just to keep on. So these things I was navigating that now I kind of know is going to happen, and I just take it and accept it. But yeah, there were lots of complicated bits. And then sort of beyond the actual physical side, it was, it’s quite a bit of India where you need lots of different permits, and it’s quite hard to get to places. So, also dealing with all the organizational stuff.

Dylan: Yeah, I mean, God, it sounds like an incredible trip. At the end of this, this was quite a big change from your normal daily life. You had sort of decided to do this wild thing, and then you did it. What was the feeling for you when you sort of got to, you know, the end of this first trip?

Elise: Yeah, it’s interesting because actually, when I was out there in—I always found, in nature, I don’t really get that anxious. And even though it’s a lot of walking and a big trip, it was the first time I kind of started to realize that, actually, when I’m in nature, I feel a lot better mentally. But I also thought, oh, because I’ve done this massive thing, when I get home, I’ll feel much better. I’ll be confident and I’ll be this whole different person. I’ll never feel anxious again. And then I got back and it was complete opposite. I was almost worse than before the trip, which was really interesting. So I put a lot on this idea of, if I can go and conquer that, like she did and do this amazing thing, then I’ll be much more confident in day-to-day life, which actually wasn’t the case with that first trip. I mean, seven years later today, I can really see how I am and how actually all of this has slowly helped me to become a more confident person. But yeah, after that first trip, I was really thrown when I got back because, yeah, I just sort of went into a bit of a shell again. And maybe it was going from a whole month of that incredible nature and being around wonderful people to suddenly being back in London in the chaos of life. Maybe that was it.

Dylan: Elise pretty quickly realized that this trip did not answer all her questions. It did not transform her into some completely new person with no problems or concerns in the world. She also realized she was not ready to stop searching. When Elise returned from her first big trip to India, she was at a loss. She was still experiencing this intense anxiety, almost, in a way, more from having been away from her life and coming back to it. So she turned to the thing that had sent her off on this adventure in the first place: books. It was Alexandra David-Néel’s book that had initially captivated Elise when she was a kid. And now, as she read through various articles and books, she discovered more and more women like Alexandra, women who had gone on these incredible adventures and perhaps been mostly forgotten to history. Elise made this long list of female explorers and, inspired by their stories, began to map out how she could retrace some of their steps, how she could take their adventures. And in 2022, there was one explorer who particularly caught her eye. Tell me about Freya Stark and The Valleys of the Assassins.

Elise: Oh yeah, I love Freya. So again, she’s actually one of the more well-known ones. She was different to a lot of women in that she published 22 books during her lifetime. And actually, a lot of them never got their books even looked at by publishers, and they all got published later by family members, things like that. So Freya was actually quite famous. She made a living out of being a cartographer and an archaeologist, and also a traveler and explorer. She wrote this book called The Valleys of the Assassins, which sounds very serious, but it’s this valley in the Alborz Mountains of Iran. And it’s famous because this sect of people that were nicknamed the Assassins just had it as a stronghold for hundreds and hundreds of years against the Mongols and people like that. And they’re just really entwined into our history. I think if you know the video game Assassin’s Creed, it’s based on this sect of people. So they’re still kind of around. And in Freya Stark’s day, people which was sort of early 1900s, people were still really fascinated by them. So she went to this valley in Iran and Persia back then in the Alborz Mountains to kind of find out a bit more about them, if she could find any sort of people that would talk to her about them. And yeah, so she went on this journey and wrote a book. And I mean, just the name of the book is pretty tempting, right? The Valleys of the Assassins. So I was like, I have to go and do this one. And I’d always wanted to go to Iran. So yeah, it was a few years ago now, so it was before everything that’s been going on there at the moment. I was really lucky that I got to go. And yeah, it was brilliant. Again, found a woman guide and just went into the mountains. Yeah, absolutely incredible trip.

Dylan: Tell me a little bit more about the trip plan. Are you going through very hot regions? Or is it cold because you’re up in the mountains? Like, how long are you going? Where’s the kind of final destination?

Elise: Yeah, so it’s—I think it’s like a four hour drive or something from Tehran. So actually, it feels remote, but it’s not that far from civilization. But honestly, I’ve never seen mountains like those. They look like Switzerland. They have really massive white peaks and then rolling green hills. And you just wouldn’t think that was kind of Iran. So obviously, it’s really hot in the valley. But once you go up into the mountains, it's really cool. And it just wasn’t what I expected. It didn’t look how I expected or anything. But obviously, a lot of Iran’s desert, so that’s a lot of what you see. But yeah, it has these pockets of these huge mountain ranges that yeah, just come up out of nowhere. It’s really incredible.

Dylan: And what was your final destination? Where were you trying to arrive to at the end of the trip?

Elise: So, we just wanted to go through the valley and follow her book. Each chapter is kind of about a different place that she visits. We just followed the book basically, and stayed with families along the way, which is what she did. And yeah, just kind of found the Assassin’s Castle, which is this famous castle of Alamut, it’s called. And that was kind of their main place where they lived. And in my head, I had, oh, castle, that sounds fun. But obviously, now it’s just a few bricks on the floor. It’s not there anymore. It’s thousands of years old. So yeah, it was interesting to see it all and to see the same sort of landscape as they would have seen.

Dylan: Anything from that trip, you know, that really surprised you about Iran? Any moments of real concern or danger just in terms of maybe the nature more than anything? Yeah, like any moments that really stand out?

Elise: There’s snakes everywhere.

Dylan: What? Really?

Elise: Yeah, like vipers in the mountains in holes, pop out of holes. I wasn’t expecting it.

Dylan: Oh, no.

Elise: I didn’t know that.

Dylan: I didn’t know that either. Did you see a lot of snakes? You saw the snakes come out?

Elise: Yeah, vipers, apparently. They were just in the path. And I’m actually okay with wildlife, but not when it kind of pops out of nowhere like that.

Dylan: No, not vipers. Vipers jumping out at you is not a thing you want to see, not really.

Elise: No, but that was a surprise.

Dylan: This trip, I think, was kind of maybe the third or so of these trips you’ve done. Like, anything you’ve learned? Like, you’re doing some of these in hobnail boots. What are the little tips and tricks you’ve learned doing these kind of pretty long, pretty intense journeys in period wear? What are some things that you’ve kind of picked up along the way?

Elise: Yeah, I mean, when you’re wearing those dresses, like, when you’re climbing up rocks, often the dress kind of gets caught underneath. So you end up doing all this stuff you don’t realize you’re doing, like hitching it up or, yeah, walking a certain way in the boots on your feet. But now it all just kind of—I just do it. But yeah, there’s lots of little things. Try not to sweat in the wool, because otherwise you get a rash. Like, all these kinds of things. And then you just work it out as you go. But yeah, I guess I don’t really think about it too much now. I just know it’s going to be a bit painful. I just put up with it.

Dylan: Is that the secret? Is the secret to just, like, no, you’re going to get, like—I assume you’re getting blisters and stuff on your feet? Hiking in hobnail boots seems insanely difficult.

Elise: Yeah, you just … And then if you feel a blister coming one place, you just lean in a different bit. And you just … In my head, I just say, you know, this isn’t forever. It’s only three days more, or two weeks more. That’s it. And then it’s gone. So that’s how I kind of work through it.

Dylan: Well, let’s talk about your most recent trip, this climb up Mont Blanc. Maybe talk to me about who inspired that particular journey.

Elise: Yeah, so I came across this woman, Henriette d’Angeville, she’s called. That’s probably a terrible French accent. But she was the first woman to climb Mont Blanc unaided. There’d actually been a woman 30 years before who went up, but she got quite altitude sick, and she got carried to the summit. So, Henriette came along and said she wanted to be the first woman to do it, just on her own, just walking to the top. And eventually just went and climbed it and made herself this incredible outfit. And she just has these amazing quotes of, like, everyone telling her she shouldn’t do it. It was a silly idea, but she just did it anyway. And that kind of thing. I just really like her attitude, and she seemed like she was quite a funny person. She’s actually on a mural in the center of Chamonix now. And we were there and I was saying to people, do you know who that is? And everyone was like, no idea. So again, she’s very unknown, considering what she did. So, yes, I really wanted to go and climb Mont Blanc.

Dylan: Around what year did she climb Mont Blanc? When was this ish?

Elise: 1838.

Dylan: Okay, that’s pretty early.

Elise: Yeah, so this outfit had to be completely made from fresh, because I’m not going to get anything from that era. And she actually made it all herself. So I just sort of made it with my mom, because actually she was just guessing. There wasn’t outdoor clothes for women. So she just guessed that trousers would probably be good under the skirt, so that the skirt didn’t blow up. And I think 1838, like, women did not wear trousers. Like, they would be shouted at in the street. They’d have things thrown at them. So often they would, like, hide them under their dresses and then go into the mountains and, like, take the dresses off and climb in their trousers and then come back down. So yeah, it was a bit like that. So she’s kind of hiding these trousers, which I think is a great part of the story. Yeah, and I just love the whole story, really.

Dylan: I love that you made, like, wool trousers and then a wool skirt to cover the trousers so people don’t shout at you while you’re climbing this mountain. Like, that’s such a sweet part of this story. Not only did you connect to the journey, but, like, the kind of crafts work that, like, preceded that journey.

Elise: Yeah, and she got the wool from Scotland because it was still very famous for its tweed then, as it is today. So I went and I found a supplier that does this amazing, sort of, tweed from the Scottish borders. And there’s no photographs of her. It’s only, sort of, pencil drawings and things like that. So I was, kind of, guessing what the colours were and things like that. And then finding out what colour clothes were in the 1830s, because I had no idea what color the clothes would be. So, we settled on this fabric that was, kind of, a bit of all the colours that they had at the time. So it’s quite something.

Dylan: You know, there’s something obviously quite paradoxical in all of this, right? You have this experience of feeling a lot of anxiety in, kind of, day-to-day life. And then you’re doing things that are, like, so far out of most people’s comfort zones, right? The idea of travelling for that long, travelling in new places. And then you’re even layering in many extra layers of complexity and, you know, just, sort of, risk in a way. Like, what do you think is going on with that relationship?

Elise: Yeah, it’s really interesting. I’ve never really put it like that before. Like, I’ve never heard it put like that. But yeah, I suppose it’s interesting, because when I’m out and I’m doing these things, I don’t get the same feelings often that I do when I’m at home and I’m in the, sort of, modern day life. And I don’t necessarily know why it is. I can only really put it down to the, kind of, being in nature. And I remember when I had my first ever panic attack and I had no idea what was going on or what it was or why I felt like I was going to die or whatever. So I just ran into, like, the nearby park that was opposite the building I was in. And I just sat in the middle of it. And then I never really knew what that connection was. But it was obviously my body just wanted to be in that green space. And then only recently I remembered that. And then I think, actually, maybe my mind just likes being in these wild spaces, even though I’m doing something a bit crazy. And again, maybe that’s it. It’s taking my thoughts away from being anxious and doing something else. But it’s interesting, yeah, because I guess these things I’m doing would make a lot of other people feel anxious. But I just, sort of, go and do them.

Dylan: I can’t help but wonder, when you’ve done one of these trips, I mean, this is experience I’ve had in a small way in my own life, which is, like, you’ve got something you’re nervous about, you know, maybe you’re, like, obsessing about a little bit. And then you do it. And you get this sense of, like, your capacity in the world kind of grows a little bit. You go, oh, okay. Like, do you feel like—is there some version of this? When you come back from these trips, does it—do you feel like now having done, you know, six of them or, you know, has it given you this sense of, kind of, greater capacity in the world? Or is it more like, I feel a little bit crazed when I’m hemmed in in the city and, like, day-to-day responsibilities, and I feel very free and open when I’m, sort of, in nature and, kind of, wandering a little bit more freely?

Elise: Yeah, it’s an interesting question. I think I’ve definitely, over time, my capacity has grown, and I can look at it from that sense. And it’s helped me in so many areas of my life, even just being calmer and being more confident and things like that. But definitely, like, a few years in, it wasn’t like that. It was how you explained. I would feel fine when I was doing it, and then I’d come back and it would be chaos. And almost like the way you put earlier, like, I would be a mess if I had to go into a room at work in an office. Like, if I had to go into a meeting room, I would just panic. Whereas I’m absolutely fine if I’m up a mountain in hobnail boots, like, clinging to the edge of a rock. Like, it just doesn’t make any sense. But now, seven years later, it’s definitely more evened out. So yeah, I have more capacity for everything. But I think it’s just time. And I think it’s just your mind slowly changing and feeling more comfortable within yourself. So yeah, I like that question. That’s, yeah, interesting.

Dylan: So, okay. So you’ve done a bunch of these. You’ve made some, like, really, you know, you’re kind of, like, challenging yourself in new, different ways with each one of these trips. What are you thinking about doing next?

Elise: So there’s a woman, actually, this year is the 130th anniversary of when she cycled around, the first woman to cycle around the world. She was called Annie Londonderry. She just cycled around the world in, like, a corset, a bike from the 1870s, which obviously has no gears, and just put a little handbag on the front thing. And that’s all she took. And she just went off around the world. So I’d really love to do something this year to kind of celebrate her. Although, yeah, this Mont Blanc, it’s so much organizing. I don’t know, but maybe September, October time could maybe try and do something. But I’d love to just get a corset and a bike, replica bike from that time.

Dylan: They, like, don’t barely have tires back then. It’s like …

Elise: No, I know. I just, this is the thing as well. You’re like, how did she do it? She cycled through the Alps. She must have pushed it up the hills, surely. I just don’t understand. So I’d love to do something to kind of honor her this year. She was great.

Dylan: You are just, like, the embodiment of the reminder that, like, you can just do things. You can just be like, this is a thing I want to do, and I’m going to figure out how to do it. And I find that very, just very delightful and inspiring.

Elise: Yeah, there’s also those things I’ve tried to do, and, you know, I’ve had to leave or run away. I remember once I was really panicky back in the day, and I had this meeting, and I literally just ran away. And I would say that that’s also okay, and that, you know, if that happens and you start beating yourself up, you shouldn’t do it because you can just have another go. So now it’s much easier for me, yes, to, like, keep going and doing things. But yeah, it does take time. Yeah, definitely. Thanks.

Dylan: Yeah, Elise, what a joy to talk to you. What an amazing project. And I truly cannot wait to see what journey you take next. The bicycle—I love cycling. So that one, I’m particularly interested in that. I thought that would be amazing.

Elise: We need to find the bike, then we can go.

Dylan: That was writer and adventurer Elise Wortley. If you want to check out more of her work, and it’s really worth digging in a little further, check out her website, womenwithaltitude.com.

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

This episode was produced by Manolo Morales. Our podcast is a co-production by Atlas Obscura and Stitcher Studios. The people who make our show include Doug Baldinger, Chris Naka, Kameel Stanely, Johanna Mayer, Manolo Morales, Baudelaire, Gabby Gladney, Amanda McGowan, Alexa Lim, Casey Holford, and Luz Fleming.

Our theme music is by Sam Tindall. And if you like the show, please, please give us a review and rating wherever you get your podcasts. And of course, you know, like, subscribe, follow. Never miss an episode. You know the drill. I’m Dylan Thuras, wishing you all the wonder in the world. I’ll see you next time.

.jpg)