Oaxaca’s ‘Mystical’ Mole of Mourning

One night in December 2021, Evangelina Aquino Luis stood in her godmother’s kitchen in Tlacolula de Matamoros, Oaxaca, crying and roasting ancho negro chiles on the comal until the room filled with smoke. The woman, who had been “like a second mother” to Luis, had just died. The next day, friends and relatives would arrive to offer condolences and follow the body to the cemetery. But that night, Luis and her two sisters were participating in another Oaxacan funerary rite. They were preparing mole chichilo. Chichilo is one of Oaxaca’s ceremonial moles, special dishes tied to specific celebrations and rites. While weddings and saints’ days call for the sweet, chocolate-tinged mole negro and the bright, tangy mole coloradito, funerals demand something darker and more complex. “Chichilo is a very bitter, very sad mole,” Luis says. That bitterness comes from the smoked chiles, roasted on the comal until nearly charring. Unlike other Oaxacan moles—which can take several days to a full week to assemble—chichilo can be made in a single night, a necessity in the case of sudden deaths. That night in 2021, Luis and her sisters spent hours in that smoky kitchen, fueling themselves with hot chocolate and slowly grinding all the ingredients into a smooth paste on the metate. You may think you can guess the flavor of mole chichilo from its contents: There’s the smoky heat of the chiles; the mildly sweet punch of roasted onions and garlic; the earthy notes of cumin; the herby tang of Mexican oregano and thyme; the hit of anise from avocado leaf; the savory creaminess of meaty broth thickened with masa. But, according to Luis, there’s one unpredictable element that will affect the chichilo’s flavor: your grief. “We call it a ‘mystical mole,’ because how the chichilo tastes depends on your suffering,” she says. “When we’re mourning our deceased relative, it’s a very bitter mole. But for other diners, the same mole may have a delicious flavor.” When the community comes together the day of the funeral, everyone gets a plate of mole chichilo before heading to the cemetery. “It’s like the last meal we eat with the body of our family member or friend,” Luis says. How it’s served varies by region, but in Tlacolula de Matamoros, it typically comes in small portions with chicken and tortillas, and washed down with horchata or hibiscus water. Funeral guests often have a second portion after the burial, and sometimes leave with a bit more to take home. Despite its ritual importance, mole chichilo remains an underappreciated, often-forgotten member of Oaxaca’s famed “seven moles” (itself a misnomer; Oaxaca has far more varieties than that). Chichilo’s obscurity, especially beyond Oaxaca’s borders, is the result of its scarcity in restaurants and the rarity of its traditional key ingredient, the chilhuacle negro chile. The chilhuacle is grown only in its native home, the La Cañada region in Oaxaca’s north. Although the area is an agricultural hotspot, with fertile land and a warm, mild climate, farmers cap their chilhuacle production at low yields. The dark, smoky pepper is particularly susceptible to diseases that wipe out entire crops and production costs are high. As a result, the peppers demand a hefty price at the market. For cooks like Luis, that price is too high. She uses the common substitution of the ancho negro chile, while others with similarly modest means might opt for the chile mulato. Recipe purists can relax: It’s not only acceptable to make substitutions or alterations when making chichilo; it’s expected. Preparations vary widely by family and region, depending on local traditions, availability of ingredients, and economic status. In the chichilo de res at her Oaxaca de Juárez restaurant Levadura de Olla, chef Thalía Barrios García includes both chilhuacle and ancho chiles, along with tomatillos, beef, and burnt tortilla ash. The latter is a common ingredient that adds a dark depth to the chichilo in García’s home region of Sierra Sur. In San Martín Tilcajete—a small village in central Oaxaca renowned as the home of the state’s alebrije makers—Azucena Zapoteca makes their chichilo with chilhuacle chiles, burnt tortilla ash, and small masa dumplings known as chochoyotes. Meanwhile, in Tlacolula, Luis offers workshops on mole chichilo at her small restaurant, Nana Vira. She was inspired to start a career as a cocinera tradicional after that emotional night cooking for her godmother’s funeral. Even as she grieved in the kitchen, she remembers feeling empowered in her role as a Zapotec elder upholding a sacred tradition. “Despite the grief and pain of losing someone so close to you, it was also a moment of pride in maintaining this tradition and passing it on to the younger generation,” she says. In the year after her godmother’s death, Luis got her chance to bring mole chichilo to a bigger stage. In March 2022, she entered a popular cooking contest in Oaxaca de Juárez and won with her chichilo recipe. In

One night in December 2021, Evangelina Aquino Luis stood in her godmother’s kitchen in Tlacolula de Matamoros, Oaxaca, crying and roasting ancho negro chiles on the comal until the room filled with smoke. The woman, who had been “like a second mother” to Luis, had just died. The next day, friends and relatives would arrive to offer condolences and follow the body to the cemetery. But that night, Luis and her two sisters were participating in another Oaxacan funerary rite. They were preparing mole chichilo.

Chichilo is one of Oaxaca’s ceremonial moles, special dishes tied to specific celebrations and rites. While weddings and saints’ days call for the sweet, chocolate-tinged mole negro and the bright, tangy mole coloradito, funerals demand something darker and more complex.

“Chichilo is a very bitter, very sad mole,” Luis says. That bitterness comes from the smoked chiles, roasted on the comal until nearly charring. Unlike other Oaxacan moles—which can take several days to a full week to assemble—chichilo can be made in a single night, a necessity in the case of sudden deaths. That night in 2021, Luis and her sisters spent hours in that smoky kitchen, fueling themselves with hot chocolate and slowly grinding all the ingredients into a smooth paste on the metate.

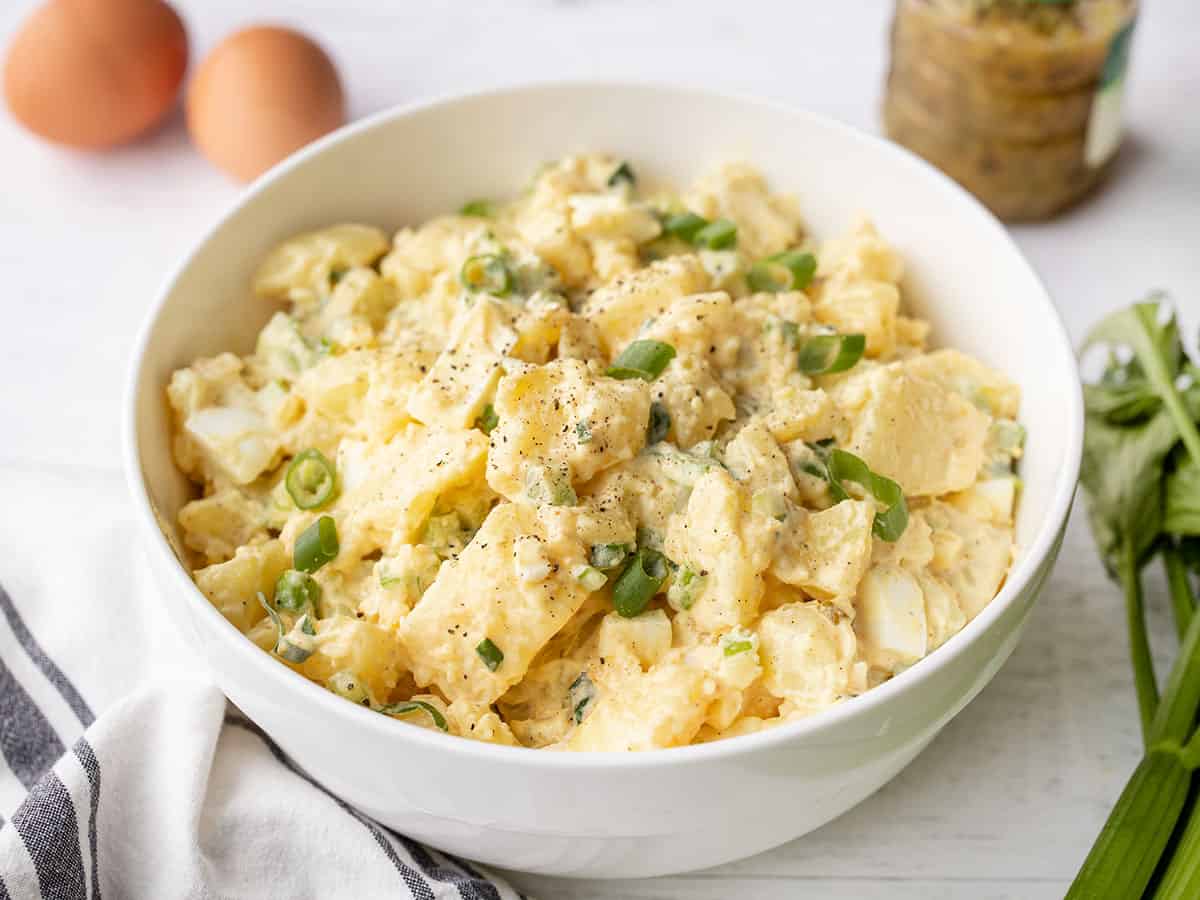

You may think you can guess the flavor of mole chichilo from its contents: There’s the smoky heat of the chiles; the mildly sweet punch of roasted onions and garlic; the earthy notes of cumin; the herby tang of Mexican oregano and thyme; the hit of anise from avocado leaf; the savory creaminess of meaty broth thickened with masa. But, according to Luis, there’s one unpredictable element that will affect the chichilo’s flavor: your grief.

“We call it a ‘mystical mole,’ because how the chichilo tastes depends on your suffering,” she says. “When we’re mourning our deceased relative, it’s a very bitter mole. But for other diners, the same mole may have a delicious flavor.”

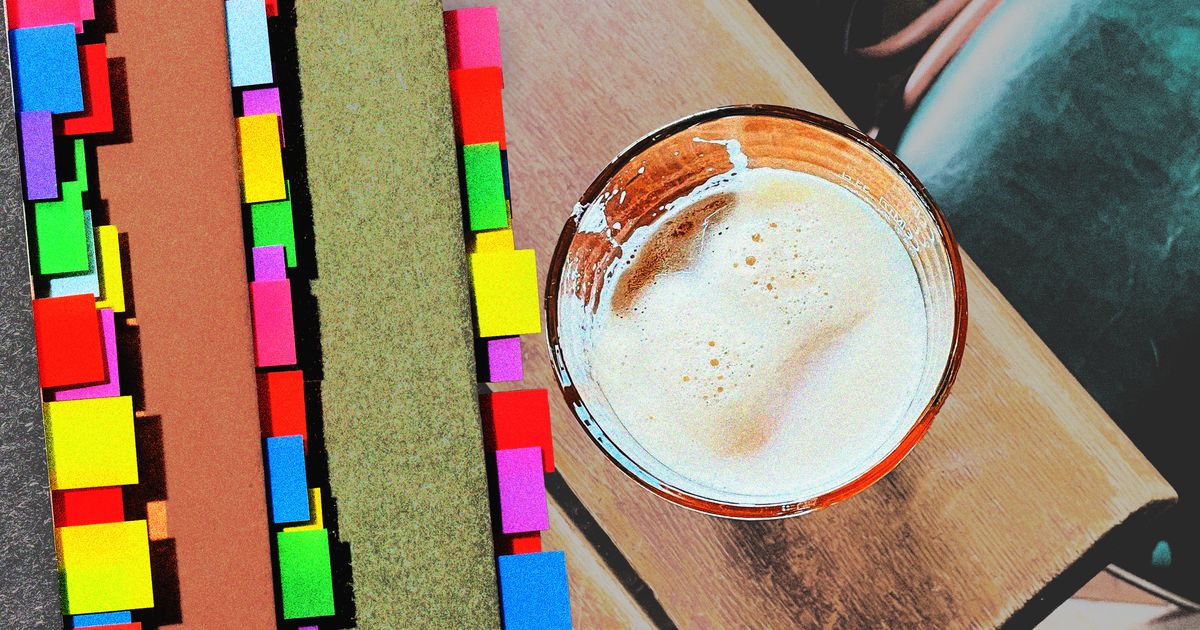

When the community comes together the day of the funeral, everyone gets a plate of mole chichilo before heading to the cemetery. “It’s like the last meal we eat with the body of our family member or friend,” Luis says. How it’s served varies by region, but in Tlacolula de Matamoros, it typically comes in small portions with chicken and tortillas, and washed down with horchata or hibiscus water. Funeral guests often have a second portion after the burial, and sometimes leave with a bit more to take home.

Despite its ritual importance, mole chichilo remains an underappreciated, often-forgotten member of Oaxaca’s famed “seven moles” (itself a misnomer; Oaxaca has far more varieties than that). Chichilo’s obscurity, especially beyond Oaxaca’s borders, is the result of its scarcity in restaurants and the rarity of its traditional key ingredient, the chilhuacle negro chile.

The chilhuacle is grown only in its native home, the La Cañada region in Oaxaca’s north. Although the area is an agricultural hotspot, with fertile land and a warm, mild climate, farmers cap their chilhuacle production at low yields. The dark, smoky pepper is particularly susceptible to diseases that wipe out entire crops and production costs are high. As a result, the peppers demand a hefty price at the market. For cooks like Luis, that price is too high. She uses the common substitution of the ancho negro chile, while others with similarly modest means might opt for the chile mulato.

Recipe purists can relax: It’s not only acceptable to make substitutions or alterations when making chichilo; it’s expected. Preparations vary widely by family and region, depending on local traditions, availability of ingredients, and economic status. In the chichilo de res at her Oaxaca de Juárez restaurant Levadura de Olla, chef Thalía Barrios García includes both chilhuacle and ancho chiles, along with tomatillos, beef, and burnt tortilla ash. The latter is a common ingredient that adds a dark depth to the chichilo in García’s home region of Sierra Sur. In San Martín Tilcajete—a small village in central Oaxaca renowned as the home of the state’s alebrije makers—Azucena Zapoteca makes their chichilo with chilhuacle chiles, burnt tortilla ash, and small masa dumplings known as chochoyotes.

Meanwhile, in Tlacolula, Luis offers workshops on mole chichilo at her small restaurant, Nana Vira. She was inspired to start a career as a cocinera tradicional after that emotional night cooking for her godmother’s funeral. Even as she grieved in the kitchen, she remembers feeling empowered in her role as a Zapotec elder upholding a sacred tradition.

“Despite the grief and pain of losing someone so close to you, it was also a moment of pride in maintaining this tradition and passing it on to the younger generation,” she says.

In the year after her godmother’s death, Luis got her chance to bring mole chichilo to a bigger stage. In March 2022, she entered a popular cooking contest in Oaxaca de Juárez and won with her chichilo recipe. In a matter of months, she was running a small cocina outside the market in Tlacolula, and in February 2023, she moved into her restaurant’s current, larger space.

For a meal so intertwined with death, Luis sees mole chichilo as a dish that transcends it, connecting her to her ancestors and generations to come. “When you make it, there’s the feeling of solidarity not just with the mourners, but with the whole community in preserving the culture. It’s keeping our customs alive, keeping ourselves alive as Zapotecs.”

Mole Chichilo

By Evangelina Aquino Luis

Ingredients

500 grams ancho negro chiles (or, if you’d like to track down chilhuacle chiles, they are available on Etsy)

250 grams sesame seeds

2 heads garlic

2 onions

Small handful cumin seeds

Small handful dried Mexican oregano (this can be found in Mexican grocery stores or markets)

Small handful thyme

8 cups broth of your choice (chicken or beef are common)

500 grams masa, mixed with 1 cup water

Salt, to taste

Instruction

1. Remove the seeds from the chiles, then toast them on a high heat on a comal or griddle, with no oil or water, until they’re darkened and smoked, but not fully charred. Toast on one side, then flip over and do the other side. (Make sure to open your windows and turn on fans; it’s going to get smoky.) Put the smoked chiles in water to hydrate for a half hour, then drain until dry.

2. Chop the onions into quarters, then separate and peel the garlic into cloves. Lightly roast the onion and garlic on the comal or griddle, with no oil or water. You just want them slightly darkened.

3. Lightly and quickly toast the oregano, cumin seeds, thyme, and sesame seeds.

4. Grind all of this on a metate or in a blender, then taste and season with salt as needed.

5. Move everything to a saucepan. Add one avocado leaf and fry everything in oil for an hour to an hour and a half until the paste thickens and almost solidifies. Do not burn it.

6. Slowly, gradually add the broth to the paste until it dissolves and creates a dark liquid. You may not need to use all of the broth.

7. Beat the nixtamalized dough, then gradually add it to the broth to thicken it. Keep stirring the mixture until it’s smooth and creamy. When it’s reached desired consistency, ladle over chicken or beef, or simply eat with some warm tortillas.

Explore more of the world’s culinary wonders with Gastro Obscura’s second annual Feast, a series of guides, stories, and recipes from our top six dining destinations of the year.

.jpg)