The Sweet Second Life of Creole Cream Cheese

My first taste of Creole cream cheese was a spoonful straight from the container, as I stood in the kitchen of an 18th-century house in the French Quarter of New Orleans. I had cracked open the lid of the white plastic tub marked “Mauthe’s” to reveal the flan-shaped curd floating in a bath of whey and cream; its texture somewhere between Greek yogurt and silken tofu. I slurped the spoonful of pale yellow cheese and could not understand how skim milk with a dash of buttermilk could taste this remarkable. It was creamy but light, with the sourness of lactobacillus, and had the kind of pungent, funky barnyard flavors I’ve never experienced in a cow’s milk product. But even beyond that, I could taste the cows because I had just spent the day with them, scratching their chins and foreheads in a field of timothy and rye grass. And I could taste the local culture, because outside the open window, I could hear the clop of mule-pulled carts, the steam whistles of ships on the Mississippi River, and the neighborhood calliope player, busking on the corner. This moment was a time capsule, a connection to the past. And while I would never be able to capture that exact moment again, it’s one that any visitor to New Orleans can find with a bite of Creole cream cheese. Creole cream cheese is a simple, fresh cheese made with skim milk and buttermilk—byproducts of butter-making—and vegetable rennet. It’s not firm like a Philly-style cream cheese; it jiggles and splits, then melts in your mouth. Traditionally, it’s sprinkled with sugar and eaten from a dish like yogurt, which was a typical French Creole way of enjoying it, or, as locals of German descent preferred, spread on buttered bread with salt and pepper. And while it’s been made in the New Orleans area for at least 130 years, it’s a local ingredient that nearly disappeared. The first known mention of Creole cream cheese by name dates to 1896, but “clabber”—milk that has been allowed to sour, then curdle, and is often eaten with sugar—is much older. A New Orleans newspaper account from 1849 notes a market vendor from St. Louis selling balls of “compressed clabber ... to be eaten with sugar but which the old lady said was first-rate with sauerkraut.” The mention calls the sugared clabber a “curious article,” suggesting the practice was unfamiliar in the region at the time. Historical recipes from the early 20th century simply call for it to be clabbered, then allowed to sit at room temperature overnight. The resulting single curd would be drained in a hanging cheesecloth or in small, circular, hole-studded molds that had come to be known as “Creole cream cheese molds” by the 1930s. It was still made and sold by commercial dairies in New Orleans through the 1970s. “What was so special about it was the taste memory of it,” Poppy Tooker told me. Tooker is a native New Orleanian raconteur of Louisiana food culture, through her NPR show Louisiana Eats! and her writing. She remembers eating Creole cream cheese as a child, having it for breakfast three or four times a week. “We’d sprinkle it with a little sugar and have it with some toast before school in the morning. It was the breakfast of champions! It’s easy to understand how you’d have a longing for it.” Poppy shared her memories with me while we sat at her kitchen table, the same kitchen where I had hastily scooped my first bite of Creole cream cheese the night before. I’ve never seen her without her hair pinned up in a swoop that highlights the silver in her hair, her makeup done with a thrilling red lip, and often an outfit that has an appropriate amount of Southern Gothic glamour. This morning, she was already in a witchy black dress and had her eyes done, and had laid out dishes of sugared Creole cream cheese and peppered cheese spread on buttered New Orleans French bread. “It’s absolutely beautiful cream cheese,” she declared of the plastic tubs of Mauthe’s Creole Cream Cheese that I had brought back from Progress Milk Barn, a dairy farm just across the state line in Mississippi. At the turn of the 20th century, there were around 300 active dairy farms operating within the New Orleans city limits; through the mid-century, Creole cream cheese was delivered with other dairy products by a milkman. But the last commercial dairy to make Creole cream cheese was Borden, and when it moved its production facility out of Louisiana in the 1980s, it discontinued the product. A family owned grocery in New Orleans, Dorignac’s, made their own cheese for a while, but changing food safety laws made production more complicated, so they stopped as well. For about two decades, this traditional ingredient could not be found in Southern Louisiana—unless you made it in your own kitchen, which Poppy did. “It’s as simple as can be,” she emphasized, showing me a plastic Chinese take-out container she had cleverly modified into a Creole cream cheese mold. As someone who had grown up eating it, Poppy was very aware Creole cream

My first taste of Creole cream cheese was a spoonful straight from the container, as I stood in the kitchen of an 18th-century house in the French Quarter of New Orleans. I had cracked open the lid of the white plastic tub marked “Mauthe’s” to reveal the flan-shaped curd floating in a bath of whey and cream; its texture somewhere between Greek yogurt and silken tofu. I slurped the spoonful of pale yellow cheese and could not understand how skim milk with a dash of buttermilk could taste this remarkable. It was creamy but light, with the sourness of lactobacillus, and had the kind of pungent, funky barnyard flavors I’ve never experienced in a cow’s milk product.

But even beyond that, I could taste the cows because I had just spent the day with them, scratching their chins and foreheads in a field of timothy and rye grass. And I could taste the local culture, because outside the open window, I could hear the clop of mule-pulled carts, the steam whistles of ships on the Mississippi River, and the neighborhood calliope player, busking on the corner. This moment was a time capsule, a connection to the past. And while I would never be able to capture that exact moment again, it’s one that any visitor to New Orleans can find with a bite of Creole cream cheese.

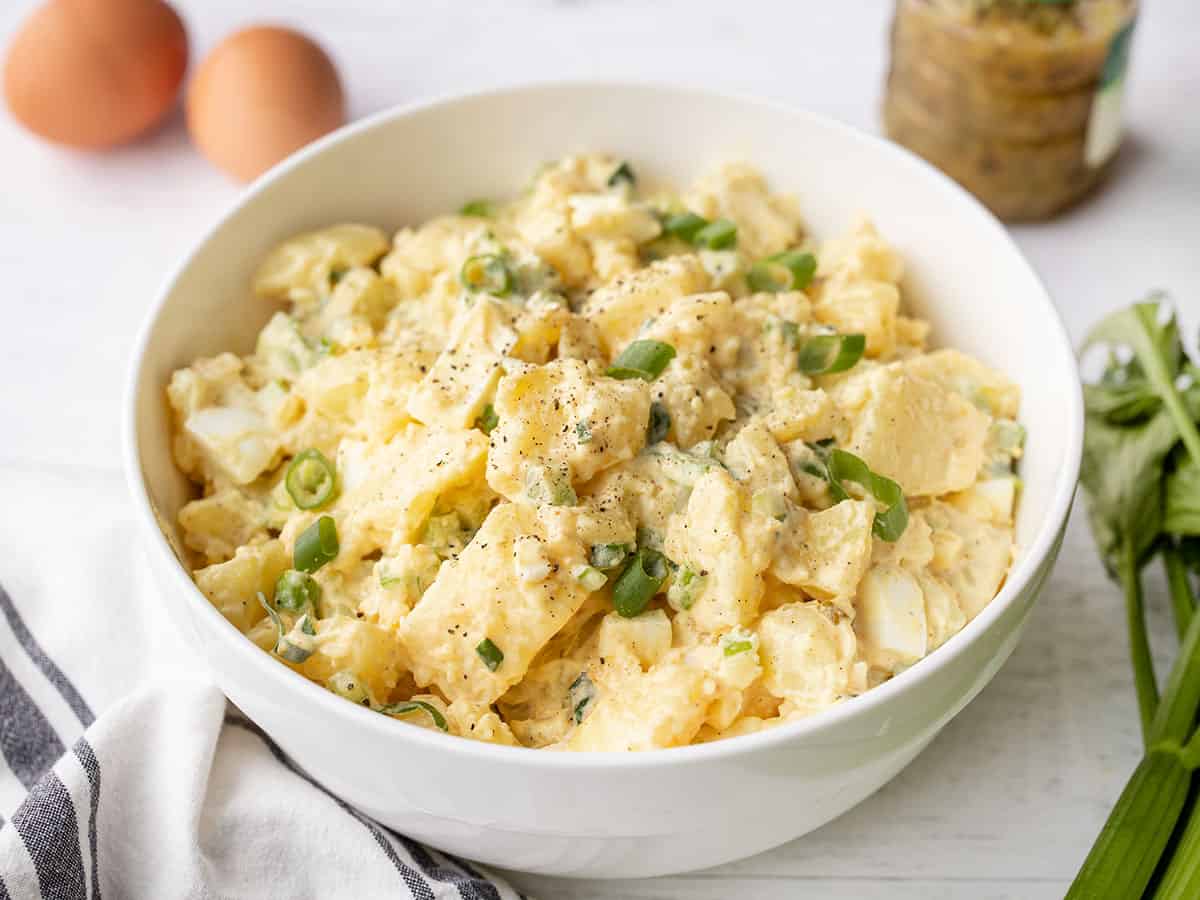

Creole cream cheese is a simple, fresh cheese made with skim milk and buttermilk—byproducts of butter-making—and vegetable rennet. It’s not firm like a Philly-style cream cheese; it jiggles and splits, then melts in your mouth. Traditionally, it’s sprinkled with sugar and eaten from a dish like yogurt, which was a typical French Creole way of enjoying it, or, as locals of German descent preferred, spread on buttered bread with salt and pepper. And while it’s been made in the New Orleans area for at least 130 years, it’s a local ingredient that nearly disappeared.

The first known mention of Creole cream cheese by name dates to 1896, but “clabber”—milk that has been allowed to sour, then curdle, and is often eaten with sugar—is much older. A New Orleans newspaper account from 1849 notes a market vendor from St. Louis selling balls of “compressed clabber ... to be eaten with sugar but which the old lady said was first-rate with sauerkraut.” The mention calls the sugared clabber a “curious article,” suggesting the practice was unfamiliar in the region at the time.

Historical recipes from the early 20th century simply call for it to be clabbered, then allowed to sit at room temperature overnight. The resulting single curd would be drained in a hanging cheesecloth or in small, circular, hole-studded molds that had come to be known as “Creole cream cheese molds” by the 1930s. It was still made and sold by commercial dairies in New Orleans through the 1970s.

“What was so special about it was the taste memory of it,” Poppy Tooker told me. Tooker is a native New Orleanian raconteur of Louisiana food culture, through her NPR show Louisiana Eats! and her writing. She remembers eating Creole cream cheese as a child, having it for breakfast three or four times a week. “We’d sprinkle it with a little sugar and have it with some toast before school in the morning. It was the breakfast of champions! It’s easy to understand how you’d have a longing for it.”

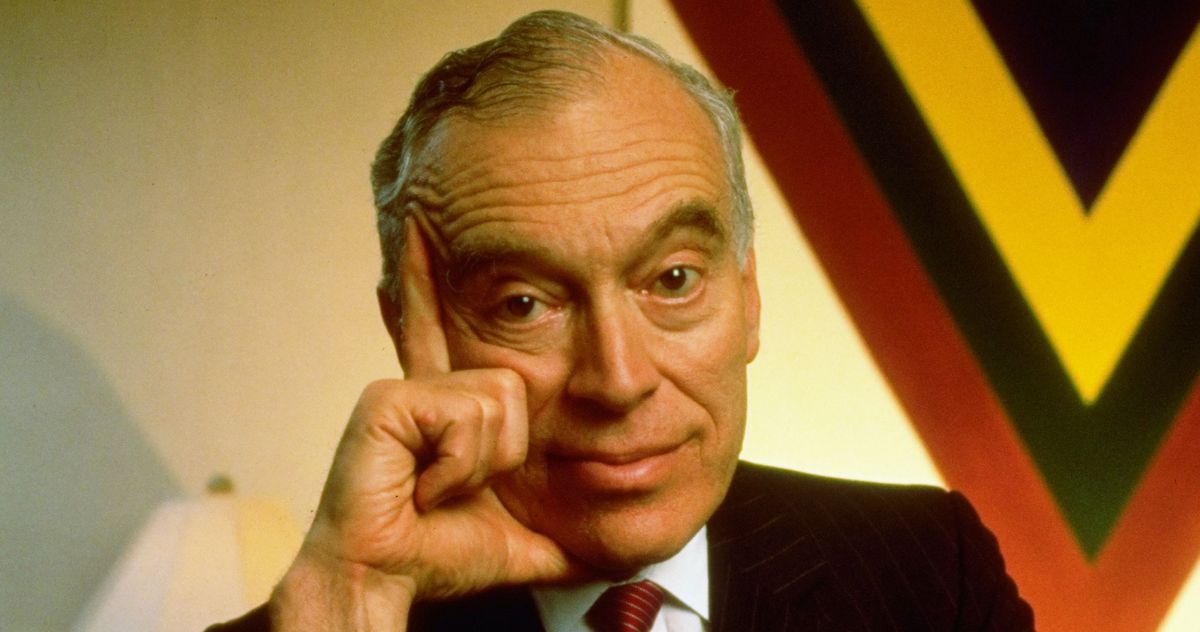

Poppy shared her memories with me while we sat at her kitchen table, the same kitchen where I had hastily scooped my first bite of Creole cream cheese the night before. I’ve never seen her without her hair pinned up in a swoop that highlights the silver in her hair, her makeup done with a thrilling red lip, and often an outfit that has an appropriate amount of Southern Gothic glamour. This morning, she was already in a witchy black dress and had her eyes done, and had laid out dishes of sugared Creole cream cheese and peppered cheese spread on buttered New Orleans French bread.

“It’s absolutely beautiful cream cheese,” she declared of the plastic tubs of Mauthe’s Creole Cream Cheese that I had brought back from Progress Milk Barn, a dairy farm just across the state line in Mississippi.

At the turn of the 20th century, there were around 300 active dairy farms operating within the New Orleans city limits; through the mid-century, Creole cream cheese was delivered with other dairy products by a milkman. But the last commercial dairy to make Creole cream cheese was Borden, and when it moved its production facility out of Louisiana in the 1980s, it discontinued the product. A family owned grocery in New Orleans, Dorignac’s, made their own cheese for a while, but changing food safety laws made production more complicated, so they stopped as well. For about two decades, this traditional ingredient could not be found in Southern Louisiana—unless you made it in your own kitchen, which Poppy did.

“It’s as simple as can be,” she emphasized, showing me a plastic Chinese take-out container she had cleverly modified into a Creole cream cheese mold.

As someone who had grown up eating it, Poppy was very aware Creole cream cheese was vanishing in the 1990s, and had been thinking about how to save it. Then, she read a piece by Sumi Hahn, the food critic for the Times-Picayune, about the Slow Food organization and their Ark of Taste, an encyclopedic reference of endangered and culturally important foods in need of preservation.

Poppy remembers thinking, This is exactly what I've been trying to do with disappearing New Orleans foods and there’s an entire international organization out there ready to help me!

Slow Food and the Ark seemed a natural fit for the culture of Louisiana. As Poppy told me: “My buddy Richard McCarthy, who founded the Crescent City Farmers Market, used to say: ‘We’ve been slow in New Orleans since anybody told us it was a good thing to be.’” Poppy called the Slow Food offices in Italy and started the New Orleans “convivia,” now simply called a Slow Food “chapter,” in 1999.

Because of Poppy, Creole cream cheese was the first American food item to be added to the Ark alongside Roman taffy candy. Soon after, Poppy onboarded two other Southern Louisiana ingredients, handmade filé powder, and the Louisiana mirliton.

But Creole cream cheese presented a unique challenge to preservation, since locals were used to buying it from commercial dairies. In August 1999, Poppy decided to host a demo for making Creole cream cheese at the Crescent City Farmers Market, so folks that were interested could make it in their own kitchens.

“And August, when there’s nothing but okra at the market, is always a treacherous time to attract shoppers,” Poppy recounted. “But that day, they said that they had a bigger crowd at the market than they ever had before in August.” The throng had come for the demo and to get a taste of Poppy’s frozen Creole cream cheese, also known as “Creole cream cheese ice cream.” “It’s really a misnomer because it’s not ice cream,” Poppy said. “It’s frozen Creole cream cheese.” In a traditional recipe, the cheese is simply mixed with sugar and vanilla, then frozen. Poppy likes to do it in ice cube trays, while some people churn it in an ice cream maker.

“And after I did that demo, within just a few weeks, I knew multiple people who were making Creole cream cheese weekly in their home kitchens,” Poppy said. “Which always spoke to me to how special New Orleanians are. Because the process of making Creole cream cheese at home involves taking a fresh dairy product [that] sits on your counter overnight.... So if you tell your average American that you’ve got this dairy product that you want them to make and eat after it has sat out for that long, your average American is going to run screaming. And your average New Orleanian is going to say, ‘Is that all I have to do to make Creole cream cheese at home?’”

In attendance at that fateful cheese demo in 1999 was Kenny Mauthe, a dairy farmer struggling to make his business profitable. To this day, Kenny credits Poppy with the dairy’s success.

I visited Kenny on his family farm, Progress Milk Barn, a little under two hours from New Orleans, in rural Mississippi. I sat down with him in a small building that serves as both an office and basic farmstand; milk, butter, cream, and Creole cream cheese cheesecakes made by Kenny’s wife, Jamie, were stacked in loudly buzzing refrigerators, battling the 90-degree heat and humidity outside.

Kenny was dressed like most farmers I’ve met, in a baseball hat and jeans, with a short gray beard and a Southern accent that could add three extra syllables to any word. He grew up in nearby Folsom, Louisiana, but his grandfather dairied in the Ninth Ward of New Orleans, delivering bottled milk and Creole cream cheese in the city. His dad also had a dairy farm, and sold his milk to a local co-op. But by Kenny’s generation, neither model was profitable. He and a business partner had already been looking into going smaller, processing the milk on-site and producing value-added products like cheese when he heard about Poppy’s demo. Kenny’s dad had even lamented how no one made Creole cream cheese anymore. After meeting Poppy, Kenny decided to become the first commercial dairy producing Creole cream cheese in over 40 years.

By May 2001, Mauthe Farms had begun producing Creole cream cheese; but initially, finding a market for it was tough and sales were slow. Then, shortly after they began, Kenny got a call from Poppy. “She said, ‘I’ve got a writer for the Times-Picayune [who] is gonna be at my house,’” Kenny told me. “And at that time, I’d probably never been to New Orleans 10 times in my life.” Jamie convinced him to go. The resulting article on Creole cream cheese was published on July 31, 2001.

For the first few months of production, if Kenny sold 50 tubs of cheese at the market, it was a good day. “The article came out Tuesday morning and we had people coming out of the woodwork.” For that Saturday’s market, they decided to bring 500 packages of Creole cream cheese. Customers lined up down the block before the market even opened; Kenny sold out in 45 minutes. “It was unreal.... They caught the bus clean across town to come get a container of cream cheese for their grandmother. And they would tell you that it brought a tear to her eye. It blew our mind.”

The demand for Creole cream cheese was so great, Progress was processing milk 24 hours a day. Kenny hired help—a former cheesemaker from the Borden plant—but still slept on-site in his truck in order to keep production going through the night.

Shortly after launching their cream cheese, they began to sell it wholesale, and it’s still available in grocery stores in New Orleans and across Louisiana, including local chains Rouses Market, Breaux Mart, and Langenstein’s. At local restaurants like the Crescent City Brewhouse and Four Seasons Hotel, it’s served as cheesecake and as ice cream.

We walked out to the pasture to meet the Mauthe family’s cows, golden-brown Jerseys, some with black furry faces that shined like satin. Known for their high milk production, Jerseys are also naturally friendly and curious. It was intimidating to have an 800-pound animal lumber in our direction, but all they wanted was deep scratches around the neck and head from Kenny. His 30 cows are all grass-fed on a seasonal mix of rye, oats, timothy, clover, and any other forage they find delicious. Their milk is naturally yellow from beta carotene, rich with vitamin A, slightly sweet, and very flavorful.

Kenny is still the only commercial producer of Creole cream cheese. His grandson wants to be a dairy farmer, but Kenny wonders what the future of this business will be like. He credits Creole cream cheese with saving his dairy, but admits it doesn’t sell as well as it used to. When they started nearly 25 years ago, many of their customers were already in their 70s or 80s. It was an older generation that had grown up eating the cheese. What they need now is a new generation to get interested in this traditional ingredient. I asked Kenny what it would take to have a run on Creole cream cheese like they did in 2001.

“That’s to be determined,” Kenny answered with a laugh.

Creole cream cheese is safe for now, “a known entity,” as Poppy puts it. “But I can’t tell you that there’s a bunch of children who are eating Creole cream cheese for breakfast, or that that tradition has been carried forward,” she told me. “But Creole cream as an ingredient was fully resurrected ... even though it’s changed a little bit.”

The change in the way Creole cream cheese is served has come largely from its popularity as a cheesecake ingredient. Jamie Mauthe makes her own popular cheesecakes, but the originator of the recipe is the storied restaurant Commander’s Palace.

Commander’s Palace originally opened in 1893 as a saloon, but within a decade had become known as a fine-dining establishment, a reputation it’s upheld to this day. The chefs that have headed the kitchen at Commander’s have included culinary legends Paul Prudhomme and Emeril Lagasse, and they also claim to have had one of the first chef’s tables in the country. It’s a booth that faces the cooking line like a dinner-theater stage. When I visited, I slid into this booth just before the start of service with Chef Meg Bickford, the first woman to be the executive chef of Commander’s Palace. Her chef’s whites were impeccably clean; her toque admirably tall and equally white.

Chef Meg started at Commander’s palace straight out of culinary school and has been there for 17 years—with the exception of a few years as executive chef at Commander’s sister restaurant, Cafe Adelaide. Her family is Cajun and Creole, and the cuisine of Southern Louisiana is her passion.

She sat down to speak with me, a dish of Creole cream cheese between us, to talk about her menu’s distinct style of “New Haute Creole Cuisine.” While some items stay the same—“I think we make the best turtle soup there is,” Meg informed me—the Creole cream cheesecake represents their combining of tradition and innovation. The skim milk cheese makes a cheesecake that is feather-light and just slightly tarter.

“It was a choice to put it back on the menu,” Chef Meg told me. “It was disappearing, you couldn’t find it readily available in grocery stores, and people just weren’t making it at home anymore. Ella Brennan, a matriarch of the restaurant, was just like, ‘We have to be a part of this revival.’”

At the time, about 1989, the restaurant had a savvy purchaser known as Miss Jill. When Dorignac’s grocery stopped making the cheese, Miss Jill convinced them to share their recipe and Creole cream cheese has been made in-house at Commander’s Palace ever since. It’s a firmer, drier curd than Mauthe’s, more like cottage cheese, and better for whipping into cheesecakes and Creole cream cheese ice cream. Their cheese has a lemony acidity that adds a flavorful tang to its custard ice cream base. Chef Meg likes it without additional flavoring, but on the menu the day I visited they featured a brownie caramel swirl ice cream with the Creole cream cheese base.

Since Creole cream cheese is commonly used in sweet preparations, Chef Meg wanted to push the envelope and find savory applications for the ingredient as well. She uses Creole cream cheese whey to finish stone-ground grits, which both brightens the flavor and gives the dish a rich and velvety mouthfeel. She also makes a roasted garlic Creole cream cheese that she serves with beets that have been roasted in a red-pepper crust.

“The beets are nice and spicy, and the cream cheese is really tangy but sweet from the roasted garlic,” she said. “It’s this incredible combination.”

Although Chef Meg strives for innovation on her menu, she believes simplicity is the key to Creole cream cheese’s survival. She feels it should be treated less as a special-occasion ingredient and become “more of a pantry item again. Creole cream cheese to us is: You put it on toast and you eat it.”

“It’s just got that special tang. It tastes like New Orleans to me.”

Creole Cream Cheese

By Poppy Tooker

Makes approximately 8 pints

Ingredients

1 gallon skim milk

1 cup buttermilk

Pinch of salt

6-8 drops liquid vegetable rennet (can be purchased in health food stores)

Instructions

1. In a large stainless or glass bowl, mix together all ingredients. Cover this lightly with plastic wrap and leave it out on the kitchen counter at room temperature for 18–24 hours.

2. You will then find one large curd cheese floating in whey. Take a pint-sized cheese mold (or make your own by poking holes in plastic pint containers with a soldering iron) and a slotted spoon, and spoon large pieces of the cheese into the molds.

3. Put the molds on a rack in a roasting pan and again cover this lightly with plastic wrap and refrigerate. Allow the cheeses to drain for 6-8 hours before turning them out of the molds and storing them in a tightly covered container for up to 2 weeks.

4. To serve, pour a bit of cream or half-and-half on top and sprinkle with sugar, or eat savory-style sprinkled with kosher salt and freshly ground black pepper.

Commander’s Palace Creole Cream Cheese Cheesecake

Makes 8 servings

Ingredients

Crust

2 cups graham cracker crumbs

½ cup sugar

8 tablespoons (1 stick) butter, melted

Filling

2½ pounds softened cream cheese (store-bought is fine)

1¼ cups Creole cream cheese

1¼ cups sugar

3 medium eggs

Topping

¾ cup sour cream

2 tablespoons sugar

For Serving (optional)

Caramel sauce

Macerated strawberries

Blueberry compote

A spectacular dessert plate

Instructions

1. Make the crust by combining the graham cracker crumbs, sugar, and melted butter in a mixing bowl. Mix thoroughly by hand, and press the crumbs evenly over the bottom and up the sides of a 9-x-3-inch springform pan. Refrigerate.

2. Preheat the oven to 250℉.

3. To make the filling, use the large bowl of a mixer with the paddle attachment to combine the softened cream cheese and sugar. Mix until smooth, occasionally scraping the bowl with a spatula. Add the Creole cream cheese and mix until smooth. Add the eggs one at a time, scraping the bowl with a spatula and mixing until smooth after each addition. Pour the batter into the prepared crust and bake for 2 hours, until the center of the cake is firm to the touch. Let the cake cool while you make the topping.

4. Combine the sour cream and sugar, and when the cake is almost at room temperature, spread the mixture over the top with a spatula. Refrigerate until completely chilled, preferably overnight.

5. To serve, release the sides of the springform pan, and cut the cake with a long knife dipped in very hot water and wiped with a clean towel after each slice. Smooth the sides of each piece with the knife. Place on a serving plate. If you wish, drizzle caramel or fruit over the top and down the sides of the cake.

Chef Tips

When you’re coating the pan with the crumb mixture, be sure the corners are not too thick with crumbs. When you mix the batter, don’t overmix or you’ll incorporate too much air and the cheesecake won’t set up properly. The trick to this cake is long, slow baking. You don’t want the top to crack or the cake to rise. And while the cake is baking, it should not have any color on top. If you’re not sure it’s done, turn off the oven, let the cake sit for 30 minutes, and remove it from the oven.

Explore more of the world’s culinary wonders with Gastro Obscura’s second annual Feast, a series of guides, stories, and recipes from our top six dining destinations of the year.

.jpg)