There’s a lot to Lumon’s vocabulary

The list of things that make Severance’s Lumon Industries incomparably eerie is long: There’s the foreboding, monolithic building filled with dizzying, nondescript hallways. There are the oft-misplaced company-sanctioned attempts at camaraderie and joy. And, of course, there’s the off-kilter vocabulary that’s indelible to the company’s control over everyone it employs (and some it doesn’t). Lumon’s […]

The list of things that make Severance’s Lumon Industries incomparably eerie is long: There’s the foreboding, monolithic building filled with dizzying, nondescript hallways. There are the oft-misplaced company-sanctioned attempts at camaraderie and joy. And, of course, there’s the off-kilter vocabulary that’s indelible to the company’s control over everyone it employs (and some it doesn’t).

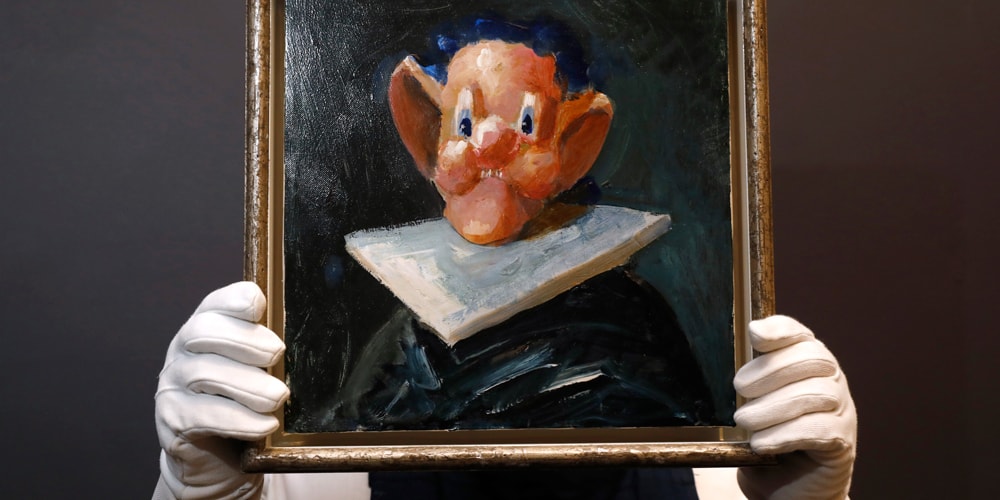

Lumon’s vernacular may at first seem par for the course for sci-fi — it’s an odd and specific repertoire that makes the viewer remember that this is not our world. In this case, though, it’s not just the writers communicating with the viewer. “Fetid moppet” is the insult Jame Eagan spits at his daughter in season 2, episode 2, after her innie escapes and makes a scene. Helena Eagan looks down in shame, or perhaps a bit of anger; the insult alone is enough punishment. The remark, literally, means “smelly child” — to our ears, a strange if not outright misplaced insult. Certainly, there is a more biting insult Jame could’ve leveled at Helena. Some might’ve even expected him to berate her at length. But at Lumon, it’s clear even just these two words make a devastating accusation and a profound offense.

That’s because Lumon has established its own vocabulary and vernacular as a method of control, and as a way to construe who is “in” and who is “out” when it comes to being in Lumon’s good graces. And like any good controlling institution, anyone at Lumon can be cast aside if they step out of line. Even Helena Eagan — heir to the company, and evidently an important part of its public image — can be denigrated with the use of just a few words.

At Lumon, words aren’t just words — they’re the extensions of Kier, and what Kier says is truth. Amanda Montell, author of Cultish: The Language of Fanaticism, writes about the way cultish groups create their own vocabulary — a code that works to establish an “us versus them” dynamic and prevent thinking that criticizes or undermines the controlling group’s ideology. Montell often uses the analogy of learning Pig Latin to describe this phenomenon — when you learn how to use it, you feel “in.”

Montell differentiates, though, between a vocabulary used to increase understanding, like medical terminology, and a vocabulary like Lumon’s. Cultish language, Montell says in this interview with Planet Word, is “there to make the exchange of information more confusing. It’s there to obscure truths.”

The “fetid moppet” insult is a great example of this. It’s archaic and muddled by nuance, but the insult is understood as it was intended: She must simply submit all of herself to him, and hope she doesn’t misstep again.

No one knows this better than Seth Milchick, the severed-floor manager whose performance review put him on blast for his vocabulary. He’s been promoted in season 2, and he’s desperate to maintain his role. He, too, employs Lumon’s eerie vocabulary and phrasing — but it’s too much, apparently. In his performance review in episode 5, Lumon rep Mr. Drummond tells him that he’s received “three contentions,” the first of which is “uses too many big words.”

Milchick tries to maintain his own ideas about how to run things. Just an episode after his performance review, he calls Miss Huang into his office to reprimand her in his own way, and it’s filled with direct language and “big words.” He tells Miss Huang that graduation from her fellowship will require “eradicating from your essence childish folly.” We still don’t know Milchick’s true thoughts, backstory, or allegiances, but one thing is clear: He is not so entrapped by Lumon’s control that he can’t think for himself. Nonetheless, he works to please or impress his superiors; he practices his new, simpler speech in the mirror, attempting to excise the parts of him that displease Lumon and its mysterious board.

Montell also talks about “thought-terminating cliches,” used to halt doubt when it arises and remind members of a group how they’re supposed to think if they want to stay inside of it. For Lumon, perhaps the most often used thought-terminating cliche is enough to get anyone to curiously capitulate: “The work is mysterious and important.” Drummond uses the phrase to convince Helena to return to the severed floor after the disastrous ORTBO in episode 5, for instance.

Lumon’s management uses similar tactics on the innies, too, flooding them with meaningless platitudes at moments when they’re confused or, importantly, when they’re threatening to rebel once again. Like Montell says, it’s about creating less clarity, not more. When Irving’s innie disappears after misbehaving during the ORTBO, for example, his colleagues know his outie has likely been fired from Lumon. Milchick calls it an “elongated cruise voyage,” though — and while Dylan’s vocal about calling this out as a lie, Mark is too uncomfortable, too confused, and too tired to resist. He accepts the non-truth, because to deny it would be to acknowledge other realities of the ORTBO, like Helena deceiving him successfully.

It’s not just the innies, or even the employees in general, that Lumon seeks to control with its idiosyncratic verbiage — it works to unsettle the viewer, too, and keeps us at arm’s length from whatever is going on inside Lumon’s doors. It’s no wonder that fans are left theorizing about Severance’s big secrets — the language of Lumon creates a fog so thick that even those raised in it can’t cut through to the reality underneath. In episode 8, when Harmony Cobel returns to her childhood home, her Lumon-allegiant aunt speaks to her in passive voice, half-truths, and obscurities. She’s Lumon through and through, and for her, it’s possible she’s outright forgotten how to speak in a typical, modern fashion. Or maybe Lumon’s is the only vernacular she speaks, instilled in her from the age she started working in that freezing factory.

-PowerWash-Simulator-2-Announce-Trailer-00-00-20.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)