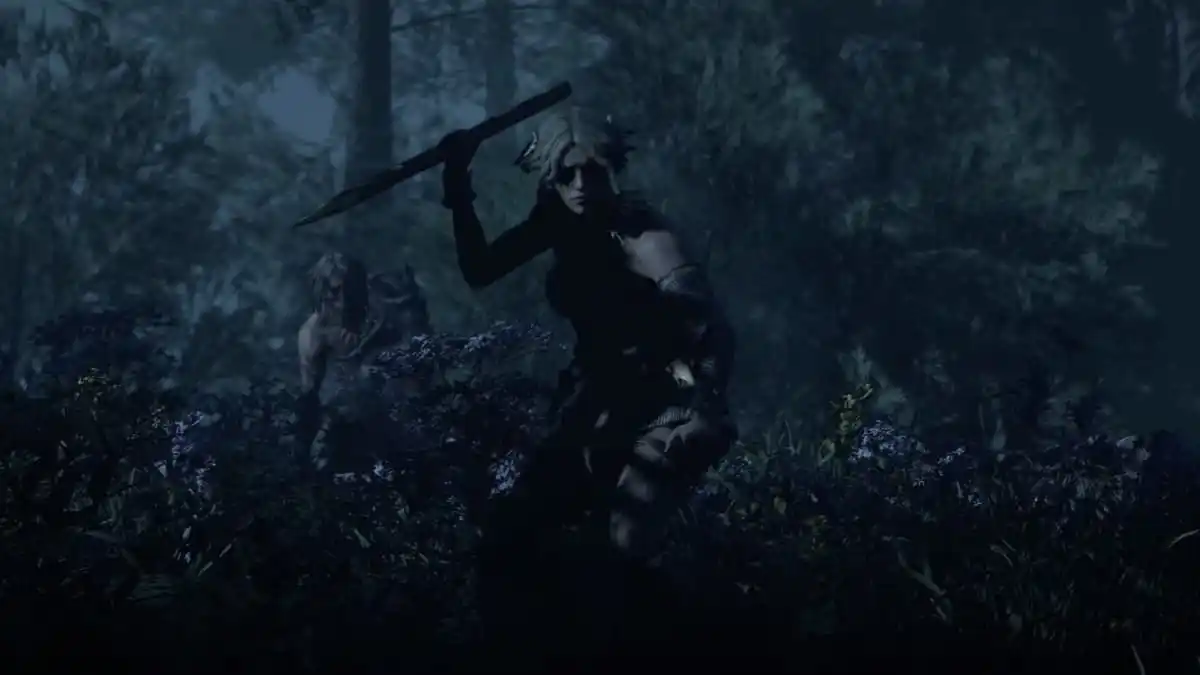

Building the light and dark in Wanderstop’s characters

Wanderstop director and co-writer Davey Wreden watched two shows when he was making the game: Better Call Saul and BoJack Horseman. The shows, he told Polygon ahead of Wanderstop’s release, “are deeply empathic stories about troubled people in a difficult world just trying to do their best.” Both of them, Wreden said, influenced the characters […]

Wanderstop director and co-writer Davey Wreden watched two shows when he was making the game: Better Call Saul and BoJack Horseman. The shows, he told Polygon ahead of Wanderstop’s release, “are deeply empathic stories about troubled people in a difficult world just trying to do their best.” Both of them, Wreden said, influenced the characters and writing in Wanderstop, which he co-wrote with Gone Home’s Karla Zimonja.

Wanderstop’s main character, Alta, is a struggling fighter who’s in a dark place. She’s not necessarily bad, but she’s absolutely troubled. You can see that in small ways, at first, like when she’s rude to customers — focused only on making tea as a means to her own ends. Then, a deeper secret is revealed, making things even more complicated. “Other mediums have had this figured out for a long time, that a story centered on a ‘bad’ person can still have a strong moral center,” Wreden said.

One of Wanderstop’s most striking qualities is that, despite Alta’s troubles, there are no judgments. When Alta ends up at a tea shop in a forest clearing, owner Boro takes her in; he’s not looking to change Alta, but instead, he helps her find clarity and healing within herself.

Polygon spoke to Wreden about these two characters and how they fit together.

[Ed. note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.]

Polygon: Last time we spoke, you said Boro specifically was an undernourished part of your creative side — that he had been neglected for so long that he just tumbled out when it was his turn.

Davey Wreden: It’s funny, I mean, I don’t literally remember saying that to you, but it makes sense. I think it’s true, but it’s kind of like, Oh wow, that is interesting.

Because I think a part of it is, which is what I said to you, is that guy, he had never really gotten a chance to come out through my work. I think I really had to spend a lot of time getting my darkness out and around this time it was like I was going through changes. I was like, I have to change the way I work. I bought a home. Suddenly everything in my mind was like, It’s time for me to get with the fucking program. And I think that was just the moment where he said, Oh, OK. And I think of myself as a combination of Alta and Boro. She is all of the intensity and all of the obsessive perfectionism in me. And then I think when people meet me, sometimes they’re surprised to be like, Oh, you’re actually just a really warm, funny guy. And I’m like, Yeah, no, I feel like I’ve never given myself permission to be that person. You’re somehow afraid of not being taken seriously anymore. Imagine these Oscar-winning movies where everyone’s so sad and dour and crying with these big tragedies or whatever. But yeah, it was just the right combination of circumstances that I felt some permission to be like, It’s OK, dude.

Are Boro and Alta designed to be opposites?

That’s one of these things that sort of came out in this early Twine prototype at that time. At that time, actually, Alta was not, she wasn’t so much — I really hadn’t defined anything about her.

She was a little bit more of a vessel, but she embodied this, I have to keep going. I have to keep going. I have to keep going. And then would come to the shop and would stay there for a minute. It’s actually really funny because this is, if you remember in The Beginner’s Guide, there’s a scene where there’s a house that you clean, and it’s in this dark space with dark on either side of it. And that came really late in the process of developing The Beginner’s Guide. That was one of the last things that went in. Even at that time, I was like, There’s something about this idea of coming to the space and it’s quiet and it’s comforting, but you have to keep going. I think The Beginner’s Guide really leans into that feeling, and again, it fully lets that go.

What was interesting was now having someone sort of pushing back on it and being like, Actually, there’s this other way too, but I didn’t want him to come in and invalidate Alta’s experience. And this is something that is jumping forward a lot in the timeline. But many years into working on Wanderstop we had all these really big conversations in the team about how much is Boro going to try to explain to Alta what’s going on and how much is he just going to let her figure it out on her own? And we had a whole lot of — it was a really difficult process of balancing like, OK, he needs to obviously contextualize a lot of what’s going on here, but any moment where he might be stepping on anyone’s interpretation of what’s going on, we have to pull that back.

It was easier for me to just put those two things next to each other and just watch them bounce off each other and not assess it, but just be like, Oh, they’re just two opposite pieces. They can exist together. There’s a trope in these kinds of guru characters that I really fucking hate, which is when the guru comes in and is like, You’re doing everything wrong and you’re so dumb, and I’m so smart, and I’m going to show you all the wise ways to be about the world, and I hate that. It’s driving me crazy. So just watching this guy almost just exist and just be like, Oh, he’s just setting an example by just existing. And we don’t need to call attention to whether or not this is complementing anything in Alta’s character. Just to watch them be in the same space is fun and feels like there’s an exciting tension to it.

Stepping down the line later on, it had to be like, OK, well, we need to build a full person around that. And that, again, was very, very difficult because now you can’t just let it be sort of vague and abstract. They have to actually talk to one another and have whole conversations with one another and say things.

I remember that we had these character models for them, and we set them. We had all these cutscenes that they’re supposed to take place in together, sitting on the bench and talking and whatever. And we had character models for them, and they’re in the game, but we didn’t have any animations. We didn’t have any fully developed animations, so we just had these placeholder animations of them just sitting statically there, just not moving at all while they have these very emotional conversations. And then we actually staffed up our animation team, and they started going through and fully fleshing out these cutscenes and giving them all the animations and all of the full personality. And the first time that I booted up the game and watched one of the cutscenes, […] it was like I was seeing these characters for the first time, and [it’s] the most beautiful experience to be like, Oh, these started in my head, but now they’re real people. And that’s the difference between a piece of work that leaves it to your imagination and one where you’re like, No, these characters could literally come out of the screen and stand next to me. I could feel them. I knew that we were going to get there eventually, but it was a long, long process of all of those tiny, tiny details that they all add up. And then one day they leap out of the screen and you meet them.

They just exist.

Yeah. They exist. You’re just like, Oh, you’ve always existed. You’ve never not existed.

One thing that struck me was that there’s a moment where Alta realizes that she did something really, really bad. But Boro doesn’t judge her for it. I haven’t experienced very much playing the character who does something that bad, and then dealing with it. But there’s no judgment. Can you talk about building that?

The scene you’re talking about when the clearing is all gray. We went through a lot of iterations of that. This is kind of what I mean is that there was an early version of that where Alta is going through this bad stuff and Boro’s trying to coach her through it.

And it was so funny. We did an internal playtest. We had everybody on the team play it through the whole game, and they got to that point, and we literally had people on the team that were like, I’m out. I won’t follow this guy anymore. He’s lost me. And for the rest of the game, they were like, I don’t care about anything Boro has to say anymore, because he came in with his lessons and his takeaways and his whatever in that scene. And actually [in the final game] he gives you a cup of tea. And that was something that someone on our team was just like, “I would so much rather he just gave me a cup of tea.” I didn’t know initially that that’s how he needed to show up.

I knew his character and I knew his tone of voice, but it was a really hard balance because he also literally has to [guide] the game. So he literally needs to be like, Here’s what you do and when and why and how. And then in other moments he just goes, “I don’t know.” And somehow it works. But I think […] because Boro has so much dialogue in this game, it’s like it is 10,000 bricks and each individual brick has to be laid correctly. And then there’s no one magic thing. It’s just, you sort of get all of them as good as you can. And then you’re like, OK, is the household standing? Yes. All right, we’re good.