Demon Oak Tree of Onizawa in Hirosaki, Japan

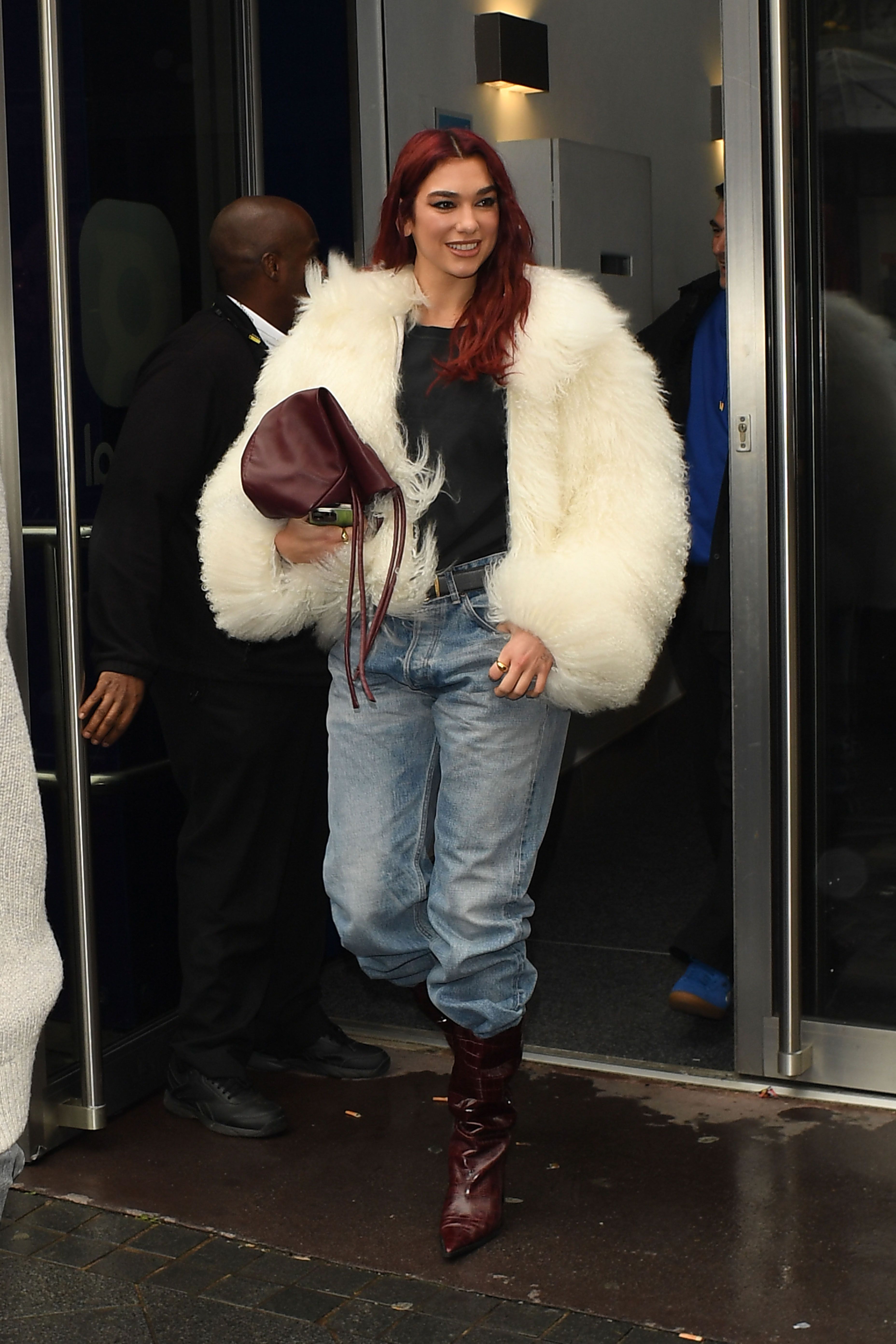

Located north of central Hirosaki, the former village of Onizawa has an evocative name. Oni, of course, refers to Japanese demons resembling two-horned ogres, powerful and strong. Naturally, there is a story behind such name. According to local folklore, a rice farmer named Yajuro once befriended an Oni from Mount Iwaki, and the two would often meet for lunch, sitting together on the branch of a great daimyo oak tree. When Yajuro mentioned that water kept leaking from his rice paddy, the Oni helped him build a steadfast canal. But when Yajuro introduced the Oni to his wife, breaking his promise to keep their relationship a secret, the Oni left the village to never return again. The daimyo oak tree survives today, believed to be over 700 years old, and known as Kishin-koshikake-gashiwa or the Demon-sitting Daimyo Oak Tree. There is a tiny shrine beside the tree, and the Oni is considered a kind of deity in Onizawa. Even during the Setsubun festival, the villagers of Onizawa are known to refuse to throw soybeans—unlike people from other parts of Japan—out of respect for the friendly demons.

Located north of central Hirosaki, the former village of Onizawa has an evocative name. Oni, of course, refers to Japanese demons resembling two-horned ogres, powerful and strong. Naturally, there is a story behind such name.

According to local folklore, a rice farmer named Yajuro once befriended an Oni from Mount Iwaki, and the two would often meet for lunch, sitting together on the branch of a great daimyo oak tree. When Yajuro mentioned that water kept leaking from his rice paddy, the Oni helped him build a steadfast canal. But when Yajuro introduced the Oni to his wife, breaking his promise to keep their relationship a secret, the Oni left the village to never return again.

The daimyo oak tree survives today, believed to be over 700 years old, and known as Kishin-koshikake-gashiwa or the Demon-sitting Daimyo Oak Tree. There is a tiny shrine beside the tree, and the Oni is considered a kind of deity in Onizawa. Even during the Setsubun festival, the villagers of Onizawa are known to refuse to throw soybeans—unlike people from other parts of Japan—out of respect for the friendly demons.