How Club Ebony Helped Keep the Blues Alive in the Jim Crow South

Listen and subscribe on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. Jala Everett: I was five years old when I heard Beyonce’s song, “Single Ladies,” for the first time. Instantly, I was hooked. These days, I’m diehard BeyHive. Plus, I’ve got deep family roots in the South. My family is originally from Tutwiler, Mississippi, a tiny town in the heart of the Delta. I grew up around family from small towns that were full of stories, soul, and music—specifically, blues music. Blues rose up from those same Delta towns. And over the years, as I’ve gotten more into blues, I found myself wanting to better understand that part of my family’s story. So, when Beyonce announced Cowboy Carter last year, the moment felt extra special. Me and my collection of cowboy boots were ready. As I listened closely, trying to spot all the signature Easter eggs Beyonce is known for, one track stood out: track 20, “Ya Ya.” “We want to welcome you to the Beyonce Cowboy Carter Act 2. Ah! And a rodeo Chitlin’ Circuit,” she said. Chitlin’ Circuit. I had never heard of it. The deeper I dug, the more I had to know. I’m Jala Everett, and you’re listening to Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Today, we’re getting a crash course in the Chitlin’ Circuit and taking a closer look at a special stop along the way: Club Ebony. It’s a place that still thumps with blues of the past, even as it welcomes a new generation of musicians. This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. Jala: You may have heard of the Green Book, a sort of underground guide that listed where it was safe for Black travelers to eat, sleep, or pick up a prescription at their local pharmacy. What you may not realize is that the Green Book also included places where you could not only be safe, but also have fun. Michelle: And in those guides, they also often list leisure clubs, so nightclubs … Jala: That’s Michelle Scott, a history professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Michelle: And so it’s kind of part of these separate travel guides that Black communities set up as business guides to allow entertainers also to know where you can perform, where there’s an audience, and where you’ll be welcomed in the segregated South. Jala: The Chitlin’ Circuit ran from Chicago to New Orleans to New York to all the cities and small towns along the way. And these clubs were essential places for Black performers to cut their chops and hone their talents. Michelle: The Chitlin’ Circuit is really the educational training ground for African American performers. Before they reach concert stages or Broadway or make recordings or they’re going to places like Motown or Stax or Chess Records, they’re really getting their start, particularly for musicians, in these small clubs, really forming a community of musicians, learning your craft, learning your vocals for the day, and then going on to the next level. Learning your craft, learning your vocals for the dancers that did appear in some of these clubs, learning the latest dances that are coming from city to city. Jala: And we’re not just talking about any old bands here. The Chitlin’ Circuit helped shape some of the most iconic musicians to ever live. Legends like James Brown, Ray Charles, and Aretha Franklin all made stops on the circuit. But in addition to building community and the musical aspect, the Chitlin’ Circuit also brought economic and political opportunity. Michelle: You have not only the space for art to develop, but that you have the space for Black business entrepreneurship to develop in these circuits, right? There are places where they are forming community and that a nightclub can, you know, entertain you—it could have a dancer, it could have a vocalist—but it could also serve as a political meeting space during the day. Jala: This all started to make sense to me when I thought about places like the Apollo Theater in Harlem or Club DeLisa on Chicago’s South Side, but as I was learning all of this, my mind kept going back to Mississippi, where my family’s from. What were the Chitlin’ Circuit clubs like there? It turns out the Mississippi clubs had their own unique character and history. Michelle: Mississippi stood out in the fact that it was one of the homes of blues music. It just became a unique place where you wanted to perform in Mississippi because you’re meeting some of the most skilled musicians but you also have some of the most lively and reciprocal audiences. They are part and parcel of the show in different clubs in Mississippi. And so you have a unique space where the art is born, but you also have the enthusiasm and the warm welcome from the audience. It’s a special place. Jala: And that’s what brought me to the small town of Indianola, to a club paint

Listen and subscribe on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Jala Everett: I was five years old when I heard Beyonce’s song, “Single Ladies,” for the first time. Instantly, I was hooked. These days, I’m diehard BeyHive. Plus, I’ve got deep family roots in the South. My family is originally from Tutwiler, Mississippi, a tiny town in the heart of the Delta.

I grew up around family from small towns that were full of stories, soul, and music—specifically, blues music. Blues rose up from those same Delta towns. And over the years, as I’ve gotten more into blues, I found myself wanting to better understand that part of my family’s story.

So, when Beyonce announced Cowboy Carter last year, the moment felt extra special. Me and my collection of cowboy boots were ready.

As I listened closely, trying to spot all the signature Easter eggs Beyonce is known for, one track stood out: track 20, “Ya Ya.” “We want to welcome you to the Beyonce Cowboy Carter Act 2. Ah! And a rodeo Chitlin’ Circuit,” she said. Chitlin’ Circuit. I had never heard of it. The deeper I dug, the more I had to know.

I’m Jala Everett, and you’re listening to Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Today, we’re getting a crash course in the Chitlin’ Circuit and taking a closer look at a special stop along the way: Club Ebony. It’s a place that still thumps with blues of the past, even as it welcomes a new generation of musicians.

This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Jala: You may have heard of the Green Book, a sort of underground guide that listed where it was safe for Black travelers to eat, sleep, or pick up a prescription at their local pharmacy. What you may not realize is that the Green Book also included places where you could not only be safe, but also have fun.

Michelle: And in those guides, they also often list leisure clubs, so nightclubs …

Jala: That’s Michelle Scott, a history professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

Michelle: And so it’s kind of part of these separate travel guides that Black communities set up as business guides to allow entertainers also to know where you can perform, where there’s an audience, and where you’ll be welcomed in the segregated South.

Jala: The Chitlin’ Circuit ran from Chicago to New Orleans to New York to all the cities and small towns along the way. And these clubs were essential places for Black performers to cut their chops and hone their talents.

Michelle: The Chitlin’ Circuit is really the educational training ground for African American performers. Before they reach concert stages or Broadway or make recordings or they’re going to places like Motown or Stax or Chess Records, they’re really getting their start, particularly for musicians, in these small clubs, really forming a community of musicians, learning your craft, learning your vocals for the day, and then going on to the next level. Learning your craft, learning your vocals for the dancers that did appear in some of these clubs, learning the latest dances that are coming from city to city.

Jala: And we’re not just talking about any old bands here. The Chitlin’ Circuit helped shape some of the most iconic musicians to ever live. Legends like James Brown, Ray Charles, and Aretha Franklin all made stops on the circuit. But in addition to building community and the musical aspect, the Chitlin’ Circuit also brought economic and political opportunity.

Michelle: You have not only the space for art to develop, but that you have the space for Black business entrepreneurship to develop in these circuits, right? There are places where they are forming community and that a nightclub can, you know, entertain you—it could have a dancer, it could have a vocalist—but it could also serve as a political meeting space during the day.

Jala: This all started to make sense to me when I thought about places like the Apollo Theater in Harlem or Club DeLisa on Chicago’s South Side, but as I was learning all of this, my mind kept going back to Mississippi, where my family’s from. What were the Chitlin’ Circuit clubs like there? It turns out the Mississippi clubs had their own unique character and history.

Michelle: Mississippi stood out in the fact that it was one of the homes of blues music. It just became a unique place where you wanted to perform in Mississippi because you’re meeting some of the most skilled musicians but you also have some of the most lively and reciprocal audiences. They are part and parcel of the show in different clubs in Mississippi. And so you have a unique space where the art is born, but you also have the enthusiasm and the warm welcome from the audience. It’s a special place.

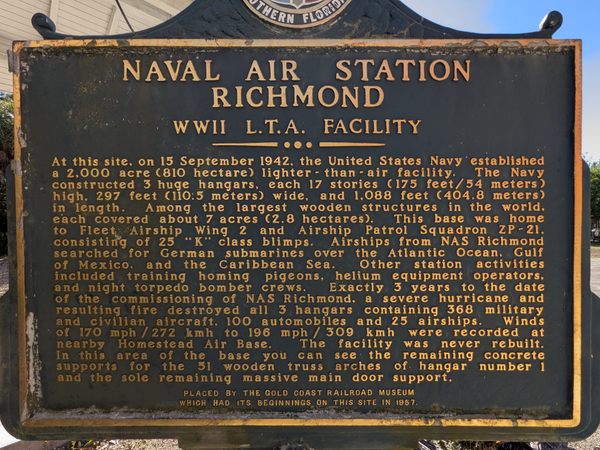

Jala: And that’s what brought me to the small town of Indianola, to a club painted green on the outside with a triangular awning and a sign on it that looked like it came out of a classic movie marquee. It read: Club Ebony. Club Ebony was one of the most legendary venues on the Chitlin’ Circuit. It opened in 1948, quickly becoming a cornerstone for blues, soul and rock and roll music.

Michelle: Club Ebony is going to showcase somebody like a Ray Charles or a B.B. King, or many of—particularly the guitarists that are a staple of blues music that are coming out of Mississippi. And it becomes a place where people know that this performer is coming in and can go to that show before their latest recording comes out, before they might have appeared on the radio. It’s kind of a hub in this network of communication between Black artists.

Jala: For the Black community in Indianola, the club was more than just music. It was a place to gather, eat, dance, and escape the harsh realities of segregation. It was where Black musicians could finally perform for audiences who understood their music and, most importantly, appreciated it. It became an integral part of the town’s social fabric.

Bill Ferris: It was inexpensive, sometimes no admission. You would simply pay for food and usually corn liquor.

Jala: Bill Ferris is a folklorist who has been studying Black music for over 50 years.

Bill: And the food often was chitlins, the cheapest meat, which is the intestines of a pig that were cleaned and served in a very beautiful, tasty dish. But it was not expensive.

Jala: That’s where the name Chitlin’ Circuit came from, by the way. Bill had visited Club Ebony and he photographed famous musicians like B.B. King as he traveled to venues across the circuit.

Bill: And B.B. as a young musician was one of those aspiring artists who later in his career came back every year to celebrate two weeks of his birthday in Mississippi. And Club Ebony was one of the places that he stopped and performed in.

Jala: Club Ebony was a hotspot, especially when B.B. was in town.

Bill: He was lionized by all the family and friends who came to say hello. And he would always welcome them, talk with them, sign autographs.

Jala: Club Ebony hosted legends like Count Basie, Jimmie Lunceford, and Grammy award-winning artist Bobby Rush.

Bill: Bobby Rush still plays that blues circuit, the Chitlin’ Circuit, from Chicago down to Jackson and then to New Orleans. He made his career in those clubs.

Jala: Club Ebony was a rarity, a bright spot for Black artistry, community, and entrepreneurship. But show business is tough in any day and age. As the years went on, Club Ebony eventually began to decline. Maintaining a venue of that size in a small town became increasingly difficult.

The walls and roof began to deteriorate. B.B. King himself even bought Club Ebony in 2008 in a last-ditch effort to keep tradition alive. Even the King of Blues couldn’t turn things around for the club, and in 2012, he left the club to a museum. But things continued to go downhill from there. In 2020, the club shut its doors.

Club Ebony sat empty for three years. But then, in 2023, the B.B. King Museum and the Delta Interpretive Center decided to give Club Ebony a major makeover to bring the club back. But this wasn’t just about fixing walls. It was about reclaiming a piece of musical history and ensuring it would continue for the future. Today, Club Ebony is open again, a living testament to the history of blues in the Chitlin’ Circuit.

Bill: Still looks like the old club, but inside, it’s a very beautiful, upgraded club, as nice as any you would ever want. And that is exactly what guests look for. And they’re thrilled to come there for concerts and to have food.

Jala: These days, a new generation of musicians perform at Club Ebony, people like Christone Kingfish Ingram, a blues artist keeping the spirit of B.B. King and others alive with every performance. This summer, when I go to see Beyonce’s Cowboy Carter show on tour, it’s fair to say the arena will be much bigger than a venue like Club Ebony. But in a crowd full of BeyHive, cowboy boots, denim on denim, bedazzled fans, and pounds of lace I’m sure to see, I’ll be thinking about the Southern musicians who made this possible. How their contributions to roots music shines through the album’s songs, and how the community and inspiration they found in the small blues venues of Mississippi still carry on their traditions decades later.

Listen and subscribe on Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Our podcast is a co-production of Atlas Obscura and Stitcher Studios. The people who make our show include Dylan Thuras, Doug Baldinger, Chris Naka, Kameel Stanley, Johanna Mayer, Manolo Morales, Baudelaire, Amanda McGowan, Alexa Lim, Casey Holford, and Luz Fleming. Our theme music is by Sam Tindall.

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)