How Texas Became an Unlikely Epicenter for Czech Pastries

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. Alexa Lim: So, you know when you’re a kid, a lot of times it’s the little things, the small things that make a big impression. And there’s a lot of childhood foods that can do that, remind you of a certain time. Maybe it was getting a Slurpee on the way to the pool with your friends, or a certain snack that your mom always gave you after school. For me, there’s this one pastry that always reminds me of road trips. I grew up in San Antonio, so my parents would pile us into the suburban, and there were usually two options: drive to Houston to visit family, or up through the hill country up to Austin. And the other thing that is also really true when you’re a kid is that road trips are pretty much the worst activity out there. Like, four hours in a car? It's almost painful. So to break up the hours of driving, we’d usually stop off in these tiny towns along the way. And they had names like Moravia and Praha. There were meat shops and restaurants with names like Little Gretel. There was definitely an old-world vibe to these towns, like you had left the Texas countryside and were transported to Eastern Europe. And usually, there was also a bakery. And this is where you would find these pastries. The kolache. A kolache is a traditional Czech pastry, sweetened yeasty dough that’s pillowy soft. And in Texas, they’re filled with fruit, cheese, and sometimes sausage. My favorite flavor was blueberry. There are dozens and dozens of these tiny towns with bakeries selling kolaches. And they’re scattered in this really specific area between the big cities of Texas, San Antonio, Houston, and Dallas. And they make up this sort of Kolache Triangle. Even as a kid, I was always curious about these towns and the story behind this Texas kolache. I’m Alexa Lim, and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange and wondrous places. Today, we’ll travel in search of the Kolache Triangle and visit some of these Czech communities and hear how the kolache became the gem of the Texas roadside snack. This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps. Alexa: Before we start, I have to clear something up. I have always called these pastries “kuh-laa-chees,” which is definitely the Texafied way of saying it. In Czech, it’s a “koh-la-ch.” And the city that can claim the title of capital of the Kolache Triangle is kind of up for debate. It probably depends on who you ask. My family, we would go to Schulenburg to get ours, because that’s a halfway point between San Antonio and Houston. Other people, they might point to the city of West, which, despite its name, is actually in the eastern part of the state. West is home to some of the most recognizable kolache and Czech bakeries. So much so that in 1997, the Texas government christened West home of the official kolache. But politicians can be fickle, as we know, because eight years earlier, they had proclaimed the city of Caldwell the kolache capital. Now, Caldwell is one of those quaint Texas towns. The main street is called Main Street. And the downtown square surrounds this towering granite courthouse. The population, just under 5,000. And there’s probably one thing that puts Caldwell on the Kolache Triangle map. Every September, around 15,000 people come to Caldwell for just one day to attend the kolache festival. And the kolache festival is basically a big celebration of all things kolache. There’s a bake-off, eating competitions, a kolache queen is crowned. But once the festival packs up, that doesn’t mean the kolaches leave with it. There are a handful of scratch bakeries in town that make the pastries year-round. Christine Campbell: I’m not a huge sweets person. I can go a whole—baking thousands and thousands of them without eating one. But then when I do want one, I can probably eat three or four. Alexa: This is Christine Campbell. She is the owner of Jake’s Bakery, where she makes kolaches by hand. Christine’s great-great-grandparents came from the Moravia region of the Czech Republic. She was born and raised in Caldwell. And today, she lives on a ranch just down the road in a house that her husband grew up in. And fun fact: their primary business is not kolaches. Christine’s husband runs a business that I’m going to say probably only makes sense on a cattle ranch somewhere out in Texas. Christine: He manages the cattle and we have a small herd of sheep. But the bread and butter is taxidermy. He does a lot of whitetail and there’s some exotic game ranches around. It’s a ride. Alexa: I mean, really, taxidermy and kolaches, kind of as Texan as you can get. Christine, as you can imagine, is busy with the ranch and taxidermy and raising her family. She’s also involved with the Czech Heritage Museum in town. So Jake’s Bakery is open exac

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Alexa Lim: So, you know when you’re a kid, a lot of times it’s the little things, the small things that make a big impression. And there’s a lot of childhood foods that can do that, remind you of a certain time. Maybe it was getting a Slurpee on the way to the pool with your friends, or a certain snack that your mom always gave you after school. For me, there’s this one pastry that always reminds me of road trips. I grew up in San Antonio, so my parents would pile us into the suburban, and there were usually two options: drive to Houston to visit family, or up through the hill country up to Austin. And the other thing that is also really true when you’re a kid is that road trips are pretty much the worst activity out there. Like, four hours in a car? It's almost painful. So to break up the hours of driving, we’d usually stop off in these tiny towns along the way. And they had names like Moravia and Praha. There were meat shops and restaurants with names like Little Gretel. There was definitely an old-world vibe to these towns, like you had left the Texas countryside and were transported to Eastern Europe. And usually, there was also a bakery. And this is where you would find these pastries. The kolache. A kolache is a traditional Czech pastry, sweetened yeasty dough that’s pillowy soft. And in Texas, they’re filled with fruit, cheese, and sometimes sausage. My favorite flavor was blueberry. There are dozens and dozens of these tiny towns with bakeries selling kolaches. And they’re scattered in this really specific area between the big cities of Texas, San Antonio, Houston, and Dallas. And they make up this sort of Kolache Triangle. Even as a kid, I was always curious about these towns and the story behind this Texas kolache.

I’m Alexa Lim, and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange and wondrous places. Today, we’ll travel in search of the Kolache Triangle and visit some of these Czech communities and hear how the kolache became the gem of the Texas roadside snack.

This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Alexa: Before we start, I have to clear something up. I have always called these pastries “kuh-laa-chees,” which is definitely the Texafied way of saying it. In Czech, it’s a “koh-la-ch.” And the city that can claim the title of capital of the Kolache Triangle is kind of up for debate. It probably depends on who you ask. My family, we would go to Schulenburg to get ours, because that’s a halfway point between San Antonio and Houston. Other people, they might point to the city of West, which, despite its name, is actually in the eastern part of the state. West is home to some of the most recognizable kolache and Czech bakeries. So much so that in 1997, the Texas government christened West home of the official kolache. But politicians can be fickle, as we know, because eight years earlier, they had proclaimed the city of Caldwell the kolache capital. Now, Caldwell is one of those quaint Texas towns. The main street is called Main Street. And the downtown square surrounds this towering granite courthouse. The population, just under 5,000. And there’s probably one thing that puts Caldwell on the Kolache Triangle map. Every September, around 15,000 people come to Caldwell for just one day to attend the kolache festival. And the kolache festival is basically a big celebration of all things kolache. There’s a bake-off, eating competitions, a kolache queen is crowned. But once the festival packs up, that doesn’t mean the kolaches leave with it. There are a handful of scratch bakeries in town that make the pastries year-round.

Christine Campbell: I’m not a huge sweets person. I can go a whole—baking thousands and thousands of them without eating one. But then when I do want one, I can probably eat three or four.

Alexa: This is Christine Campbell. She is the owner of Jake’s Bakery, where she makes kolaches by hand. Christine’s great-great-grandparents came from the Moravia region of the Czech Republic. She was born and raised in Caldwell. And today, she lives on a ranch just down the road in a house that her husband grew up in. And fun fact: their primary business is not kolaches. Christine’s husband runs a business that I’m going to say probably only makes sense on a cattle ranch somewhere out in Texas.

Christine: He manages the cattle and we have a small herd of sheep. But the bread and butter is taxidermy. He does a lot of whitetail and there’s some exotic game ranches around. It’s a ride.

Alexa: I mean, really, taxidermy and kolaches, kind of as Texan as you can get. Christine, as you can imagine, is busy with the ranch and taxidermy and raising her family. She’s also involved with the Czech Heritage Museum in town. So Jake’s Bakery is open exactly one time every month, just 12 times a year. But she grew up eating and making kolaches with her grandma. And it was really important to her to preserve that tradition. So each month, on one Saturday, she heads out from the ranch at 4:00 a.m. to start her dough.

Christine: Some of the things I measure out, like my liquids and my eggs. But I’m not exactly sure how much flour I put in it. And it’s just kind of a field. And that’s kind of it. You let it rise and then we’ll roll them out. I do it kind of an old-fashioned way. I have an old can that I just cut them out with.

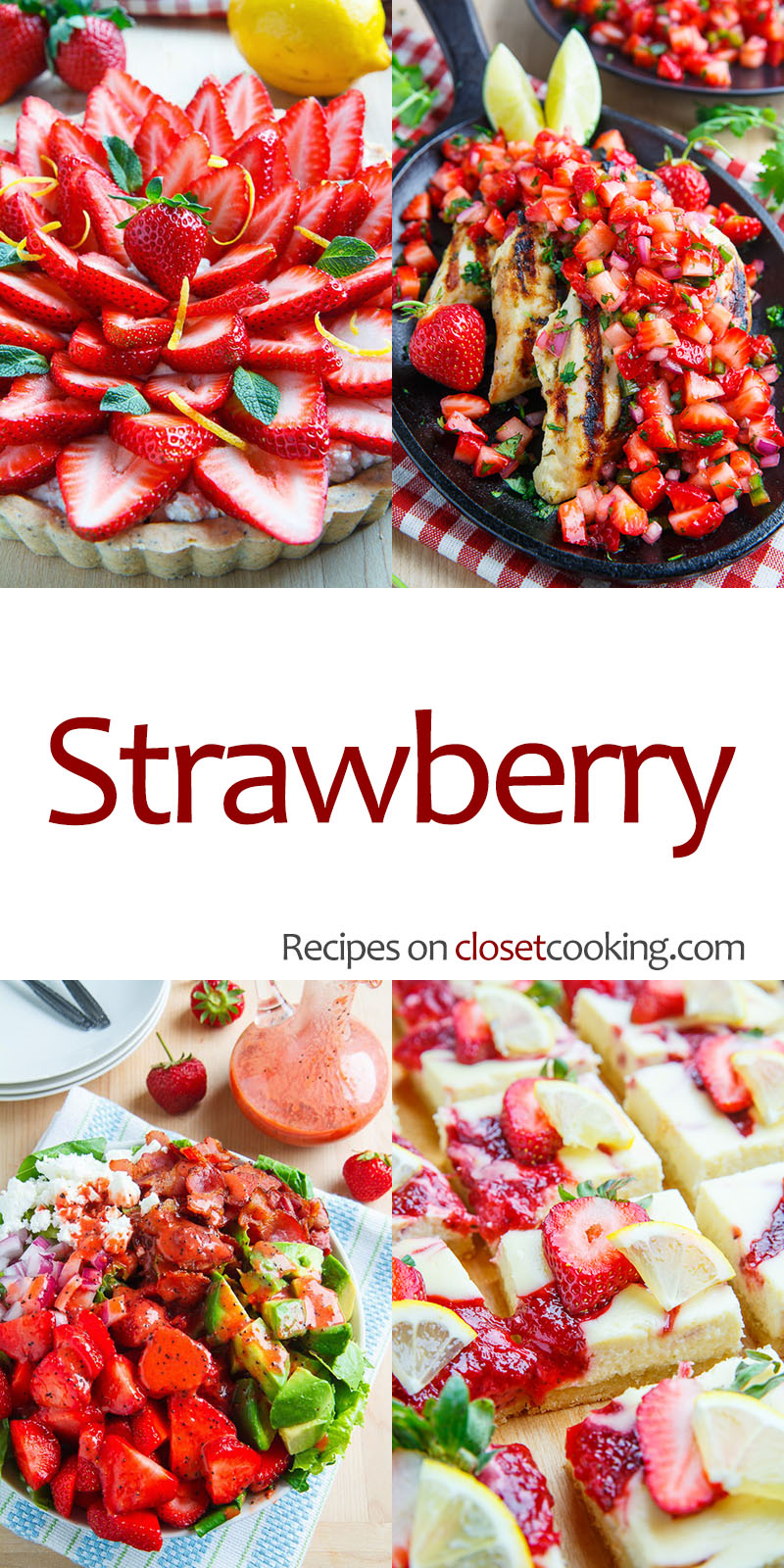

Alexa: A kolache has three basic parts. There’s the sweetened brioche-like bun, a crumb topping called pupsitka, and then the fillings.

Christine: Cream cheese is easily our best seller. But back in the day, they didn’t have cream cheese. They’d make cottage cheese and prune and poppy seed and apricot. My favorite is probably a mixture. We’ll do a poppy cream cheese mix. So it’s kind of the Hannah Montana of kolaches.

Alexa: Christine uses the recipe from her grandmother. She has tweaked it here and there, but she basically sticks to the same formula. And on a regular Saturday, she’ll roll out 2,400 kolaches. And they sell out. We have some folks that come from Temple or from Houston or from Industry, which is an hour away just to get kolaches and go back home. And a kolache is the type of thing that people will go out of their way to get. But for Christine and a lot of people, they’re more than just a pastry. There’s this big cultural connection. And how the kolache first made it to Texas runs back 150 years. So the Kolache Triangle is also home to the largest population of Czech Americans in the country. But that’s not how they describe themselves.

Dawn Orsak: Texas Czechs, for some reason, put the qualifier after. So they’re Texas Czechs versus calling themselves Czech Americans. And I think that says something about the community, how proud they were of immigrating to Texas.

Alexa: This is Dawn Orsak. She’s a third-generation Texas Czech, and she’s writing a cookbook about the community. The first Czech immigrants started moving to Texas in the late 19th century. A lot of them were farmers, and there was a lot of social and political conflict happening in the Czech Republic. And at the time, Galveston was a major U.S. immigration port. So a lot of Czech farmers landed in Texas, and many of them moved to the Blackland Prairies because it was great for farming. And those prairies sit right inside the area of the Kolache Triangle.

Dawn: Texas’ Czech immigrant community was unique in that they really isolated themselves, not necessarily by choice, but because they were settled in rural areas.

Alexa: Texas Czech towns started popping up all over the place. There were 250 Czech communities across the prairie land. And of course, they brought their food and traditions to these towns. And there’s still a lot of Czech influence in Texas. Polka? Czech. Shiner Bock beer? Czech. And of course, the kolache. And the kolache has been given a sort of Texas makeover. There were a few key differences. Like my favorite blueberry flavor, probably not so traditional. The traditional fillings would have come from fruits off their trees, like plums and apricots. But of course, in Texas, they had to use what they could find. So prunes were substituted for plums. Instead of sweetened cheese, you’ll now find cream cheese. And there were some other interesting flavors.

Dawn: But in the Czech Republic, they would have eaten a sweetened cabbage filling that I’ve heard called zelniky, that is really just shredded cabbage with butter, salt, pepper, and sugar. And they definitely would have eaten kolaches that were filled with poppy seeds, ground and mixed with milk, cinnamon, sugar, maybe a little lemon zest, sometimes raisins.

Alexa: Texas kolache dough is a little sweeter and fluffier. They’re known for this iconic shape, this thick square that sits almost one inch high off the pan. The Czech versions are rounder and flatter. And kolache, they weren’t usually eaten on a daily basis.

Dawn: When I was growing up, the only people who ate kolaches were Texas Czechs. Baking kolaches is too much trouble to have them on a daily basis. If you’re making them yourself, they were a family gathering or community gathering food.

Alexa: Dawn remembers eating them at church picnics, polka dances, and family reunions. So how did the pastry make it from these family events and into the grab-and-go snack that I ate on road trips? Well, one of the places that really helped popularize the pastry was the Village Bakery in West. Remember, that’s the city that’s actually located in the east. It opened in 1952 and claimed to be the first all-Czech bakery in Texas, and it focused on the kolache. So it kind of helped introduce the pastry to non-Czech customers. And today, you’ll find some of the most famous kolache bakeries in gas stations, which might sound like an odd combination, but it really took advantage of being on that highway system that connected the big cities, catching passing commuters or kids stuck in the back of a van on a family road trip. And that helped the kolache spread to people outside of the Triangle. Now, big commercial and non-Czech bakeries make these pastries. And they’ve become so popular that they’ve kind of gone the way of the donut.

Dawn: Fillings have gotten, you know, out of control, crazy, from peanut butter and jelly to cream cheese with a Hershey bar stuck in the center. The fillings have become Americanized and made more for mass tastes.

Alexa: It really does feel like you can find them in any convenience store. They’re even sold in a certain beaver-themed mega gas station.

Dawn: For many Texas Czechs, it’s an eye-rolling experience. It just seems to be the way of immigrant food in America. I mean, you know, did Italians in the 19th century, do they cringe in their graves seeing slices of pizza at 7-Eleven in the warming ovens? You know what I mean? There’s no way that culture’s food gets transplanted to another country, and 150 years later, it’s exactly the same. It’s not possible. And certainly the kolaches that some people, like my children, think of as traditional because their grandmother made them, and that’s even different from what my grandmother made or my grandmother’s grandmother made. So authenticity, you know, what does that even mean at over 150 years?

Alexa: So in Texas, the kolache has made it into the immigrant food mash-up pantheon, right up there with breakfast tacos. And even though a Hershey kolache is probably not what the original Czech farmers had in mind and might induce an eye-roll, there is a certain pride about it.

Dawn: How could you not be proud that your family, your culture’s traditional food is being appreciated by outsiders? But I think the counter to that is that Texas Czechs have to carry on the traditional way of making kolaches and the traditional flavors so that there is the authentic to always compare to.

Alexa: And what Dawn and Christine really hope is that people kind of understand the history and tradition baked inside the beloved kolache.

Christine: It’s a little bit deeper than just a pastry. Because it does, it tastes like a certain memory. It tastes like a certain person. It tastes like a certain holiday or a certain time in your life. But to those folks that don’t have that cultural connection to it, it’s just good. It’s all the good things in one little handheld package.

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Our podcast is a co-production of Atlas Obscura and Stitcher Studios. This episode was produced by Alexa Lim. The people who make our show include Doug Baldinger, Chris Naka, Kameel Stanley, Johanna Mayer, Manolo Morales, Beaudelaire, Gabby Gladney, Amanda McGowan, Alexa Lim, Casey Holford, and Luz Fleming. Our theme music is by Sam Tindall.

![nqz "I would be lying if I said I don't [feel pressure]. It was so different for me to see all those people and be in a Major playoffs"](https://img-cdn.hltv.org/gallerypicture/kAkShxXB96gCZmlpU-ivfH.jpg?auto=compress&ixlib=java-2.1.0&m=/m.png&mw=107&mx=20&my=474&q=75&w=800&s=935037b04cd96d3e70935ccfb24c348e#)

![What’s in Hilary Duff’s Shopping Cart [Exclusive]](https://cdn.apartmenttherapy.info/image/upload/f_auto,q_auto:eco,c_fill,g_auto,w_660/k/Design/2025/06-2025/alacart-hillaryduff-lead)