Raising a Ghost Town From the Dead

Exploring the remnants of the former Brownsville General Hospital was a terrifying experience, even for me. It wasn't just that the building was creepy, although it certainly was: full of long rooms lined with rusting hospital beds covered with chunks of paint and plaster, it felt like the real-world embodiment of every haunted place in a horror movie. Though I don't put much stock in the supernatural, that doesn't mean I'm immune to my imagination or the nagging suspicions that if ghosts did exist, places like this would be where they would find me. The more pressing concern was the structural condition of the building. Entire rooms had collapsed into the basement, shards of wood and jagged metal protruding from the wreckage like a punji pit. A bathroom clung to one wall of a hallway, dangling over the chaos below by the pipes in its plumbing. The floors that did remain were warped and uneven, and the stairs had gaping holes in them. It felt like the old hospital was just waiting for an excuse to entirely cave in, and my weight in the wrong spot might be the catalyst. The Brownsville General Hospital, which operated in its final years as the Golden Age Retirement Home, was not an anomaly in the small Western Pennsylvania town of Brownsville. Barely a mile away on Market Street, the downtown core presented visitors with a panoply of devastation. There, you'd find the remains of the First Baptist Church choked in ivy; the majestic, neoclassical facades of the Monongahela National Bank and the Second National Bank boarded and stained; the gorgeous five-story Union Station with ragged awnings serving as funeral shrouds over the windows of long-forgotten businesses. In a short stretch, you'd pass the abandoned husks of the town's hotel, apartment buildings, restaurants, and stores—nearly all of which were vacant. Even from the street, you could see that significant portions of the roofs and walls were caving in. The windows that weren’t boarded up were shattered, with fragments of blinds fluttering in the breeze. Their interiors had fared little better (and sometimes dramatically worse) than the Brownsville General Hospital. It was hard even to tell what some had been. I have visited many small Rust Belt towns that were struggling economically, but I had never seen losses of this magnitude. Established in 1785, Brownsville flourished as an outfitting hub on America's first Federal highway, the National Road, and its location on the riverfront contributed to its continued success as a builder of steamboats. As the rail and steel industries proliferated in Western Pennsylvania, Brownsville added a railroad yard and a coking center, cementing its status as an integral part of the region's industrial dominance. But in the 1970s, the same cataclysmic contractions in the steel industry that ravaged other Rust Belt towns decimated Brownsville's population and economy. The population, which had peaked at over 8,000 in the 1940s, plummeted over the decades—by the 1990s, just over 3,100 lived there. This decline set the stage for a new type of blight unique to Brownsville: a type of property hoarding that would hold the town hostage for decades. By the early 1990s, many of the town's historic properties were being sold for as low as a dollar at tax sales, with the hopes of luring investors with a vision for the town's future. Entrepreneurs Ernest and Marilyn Liggett went on a buying spree and scooped up over a hundred buildings, including an estimated 75–95 percent of the downtown. Initially, they seemed like Brownsville’s saviors. They spoke of grand plans for a wharf and marina, which were torpedoed by the Waterway Association of Pittsburgh in 1993–94. Then, it was an ambitious project to bring riverboat gambling to the town, which was shot down by the Pennsylvania State Senate in 2011. After that, a plan to bring a velodrome, or bicycling arena, to the town came and went. According to former mayor Norma Ryan, the Liggetts increased rent in properties like the Union Station in anticipation of rising property values, forcing tenants out. As the decades wore on with no sign that any of the Liggetts' proposals would materialize, sentiment in the town turned from hopeful to angry. The properties the Liggetts had purchased weren't being maintained, and their condition was rapidly deteriorating. Though Ernest was still raising money from investors, it appeared to the people of the town that he was doing little more than letting the buildings crumble. By 2007, Liggett quit paying taxes on the buildings, and ignored the city's citations for code violations. His investors successfully sued him, but couldn't recover any of their money. When the town sued Ligget, he countersued. Every time the borough tried to seize properties, Liggett figured out ways to thwart their efforts. Even when he was forced to put properties up for sale, he set the minimum bids to unrealistically high numbers, preventing potential buye

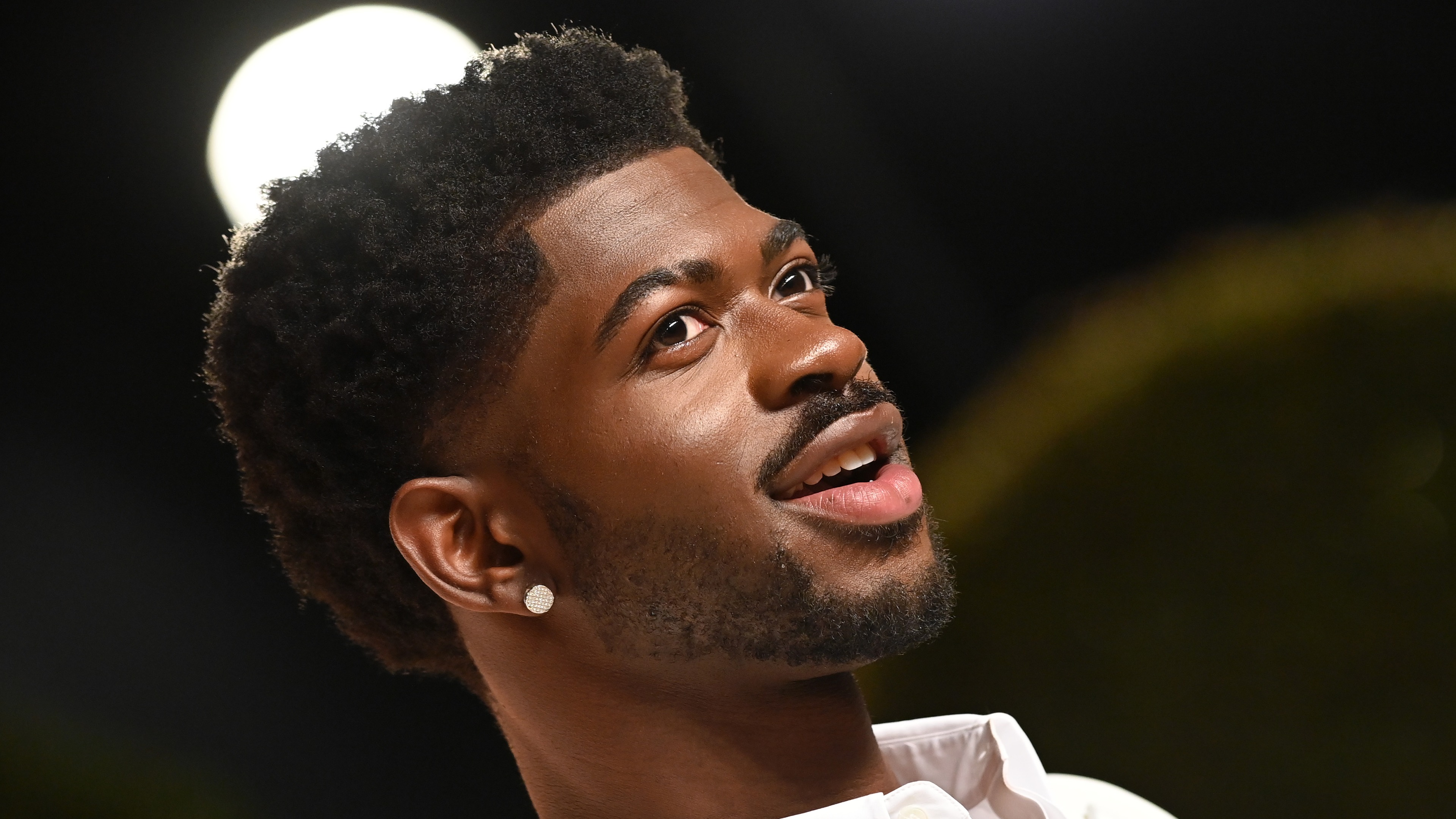

Exploring the remnants of the former Brownsville General Hospital was a terrifying experience, even for me. It wasn't just that the building was creepy, although it certainly was: full of long rooms lined with rusting hospital beds covered with chunks of paint and plaster, it felt like the real-world embodiment of every haunted place in a horror movie. Though I don't put much stock in the supernatural, that doesn't mean I'm immune to my imagination or the nagging suspicions that if ghosts did exist, places like this would be where they would find me.

The more pressing concern was the structural condition of the building. Entire rooms had collapsed into the basement, shards of wood and jagged metal protruding from the wreckage like a punji pit. A bathroom clung to one wall of a hallway, dangling over the chaos below by the pipes in its plumbing. The floors that did remain were warped and uneven, and the stairs had gaping holes in them. It felt like the old hospital was just waiting for an excuse to entirely cave in, and my weight in the wrong spot might be the catalyst.

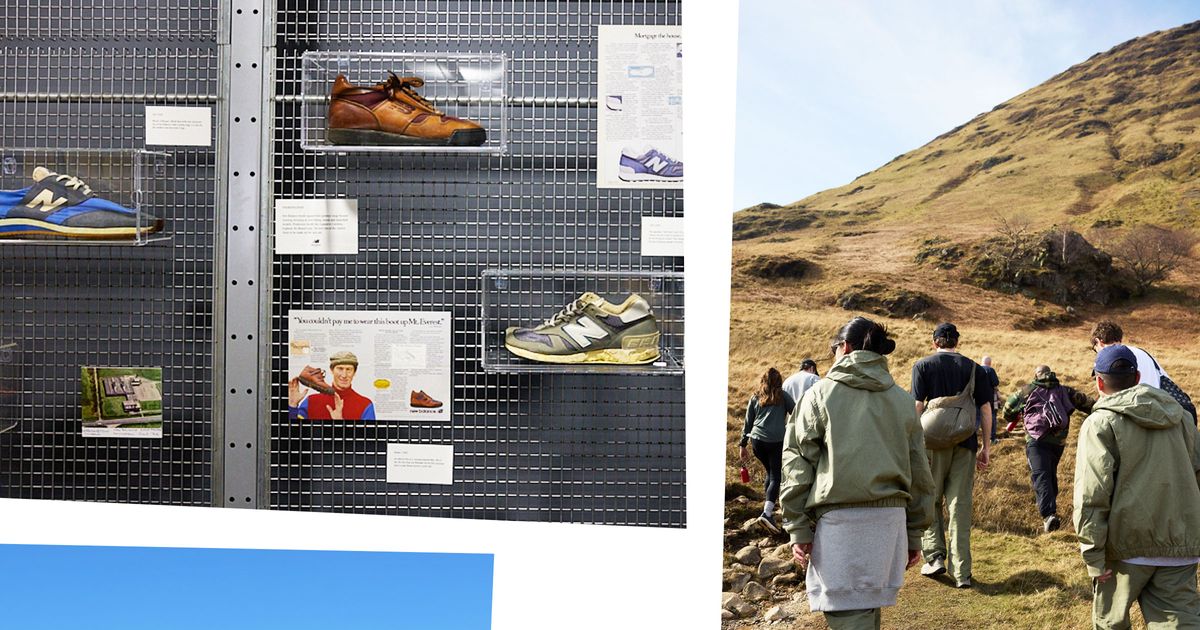

The Brownsville General Hospital, which operated in its final years as the Golden Age Retirement Home, was not an anomaly in the small Western Pennsylvania town of Brownsville. Barely a mile away on Market Street, the downtown core presented visitors with a panoply of devastation. There, you'd find the remains of the First Baptist Church choked in ivy; the majestic, neoclassical facades of the Monongahela National Bank and the Second National Bank boarded and stained; the gorgeous five-story Union Station with ragged awnings serving as funeral shrouds over the windows of long-forgotten businesses.

In a short stretch, you'd pass the abandoned husks of the town's hotel, apartment buildings, restaurants, and stores—nearly all of which were vacant. Even from the street, you could see that significant portions of the roofs and walls were caving in. The windows that weren’t boarded up were shattered, with fragments of blinds fluttering in the breeze. Their interiors had fared little better (and sometimes dramatically worse) than the Brownsville General Hospital. It was hard even to tell what some had been. I have visited many small Rust Belt towns that were struggling economically, but I had never seen losses of this magnitude.

Established in 1785, Brownsville flourished as an outfitting hub on America's first Federal highway, the National Road, and its location on the riverfront contributed to its continued success as a builder of steamboats. As the rail and steel industries proliferated in Western Pennsylvania, Brownsville added a railroad yard and a coking center, cementing its status as an integral part of the region's industrial dominance. But in the 1970s, the same cataclysmic contractions in the steel industry that ravaged other Rust Belt towns decimated Brownsville's population and economy. The population, which had peaked at over 8,000 in the 1940s, plummeted over the decades—by the 1990s, just over 3,100 lived there. This decline set the stage for a new type of blight unique to Brownsville: a type of property hoarding that would hold the town hostage for decades.

By the early 1990s, many of the town's historic properties were being sold for as low as a dollar at tax sales, with the hopes of luring investors with a vision for the town's future. Entrepreneurs Ernest and Marilyn Liggett went on a buying spree and scooped up over a hundred buildings, including an estimated 75–95 percent of the downtown. Initially, they seemed like Brownsville’s saviors. They spoke of grand plans for a wharf and marina, which were torpedoed by the Waterway Association of Pittsburgh in 1993–94. Then, it was an ambitious project to bring riverboat gambling to the town, which was shot down by the Pennsylvania State Senate in 2011. After that, a plan to bring a velodrome, or bicycling arena, to the town came and went. According to former mayor Norma Ryan, the Liggetts increased rent in properties like the Union Station in anticipation of rising property values, forcing tenants out.

As the decades wore on with no sign that any of the Liggetts' proposals would materialize, sentiment in the town turned from hopeful to angry. The properties the Liggetts had purchased weren't being maintained, and their condition was rapidly deteriorating. Though Ernest was still raising money from investors, it appeared to the people of the town that he was doing little more than letting the buildings crumble. By 2007, Liggett quit paying taxes on the buildings, and ignored the city's citations for code violations. His investors successfully sued him, but couldn't recover any of their money. When the town sued Ligget, he countersued. Every time the borough tried to seize properties, Liggett figured out ways to thwart their efforts. Even when he was forced to put properties up for sale, he set the minimum bids to unrealistically high numbers, preventing potential buyers from making offers.

Fighting costly legal battles was a challenge for a cash-strapped borough, and lack of funding led to police and municipal workers being laid off for several months. The town had difficulty acquiring federal redevelopment funds since they were seeking to demolish buildings on the National Register of Historic Places. Bit by bit the town clawed back the buildings from the Liggetts through the power of eminent domain.

In 2020–21, they demolished the former Brownsville General Hospital, which was little more than a shattered husk by the time of acquisition. Multiple buildings on Market Street were demolished, making way for a new senior housing development. Hope Park was built across the street, offering residents a walking path, green space, and a screen for outdoor movies. The Flatiron Heritage Center opened in a once-abandoned structure on Market Street, offering visitors a chance to experience the region's history and art. The process is far from complete, with many more buildings still awaiting rehabilitation or the wrecking ball, but progress is being made. Market Street looks less like a ghost town with every passing year. Slowly but surely, the local businesses that sustain a downtown core are making their way back now that they have the opportunity to do so.

The loss of so many beautiful buildings, the physical expression of the town's rich heritage, still stings. By the time I first visited in 2009, the ruins of the former Brownsville General Hospital and adjacent Horner Memorial Nurses' Home were far too dilapidated to save. Even someone as hell-bent on preserving neglected structures as I am could see that there was almost nothing salvageable. The interior was a death trap, and the outer walls and roof were severely compromised. "Saving" the building would almost certainly necessitate removing tons of rubble and debris, stabilizing the remains of the exterior, and completely rebuilding it—an enormous expenditure without much to justify it.

For a town that had so many neglected structures lingering as reminders of stagnation for decades, I could certainly understand the desire to move forward no matter the cost. A town serves the living, not the dead. But as I sat in the library, watching an old newsreel showing the heyday of Brownsville's downtown when the sidewalks were crowded with shoppers and the future seemed bright and full of promise, the toll of Ernest Liggett's failed pie-in-the-sky projects seemed unconscionably severe. Though he hadn't created the recession that imperiled the region, the residents that I spoke to agreed that he had stifled Brownsville's ability to recover from it. To this day, the Liggets' motivation remains a mystery to the people of Brownsville. Regardless of whether their efforts were borne of a futile attempt to wring money from a destitute town or a misguided hope that they could improve it, the scars from their actions will linger for many years to come, either in the form of decaying historic sites—or in their absence.

For more photos and history about the town of Brownsville and an interview with former mayor Norma Ryan, visit Abandoned America.

Matthew Christopher is a writer and photographer who has explored abandoned locations across the globe for two decades, chronicling the lost landmarks in our midst. You can find more of his work on his website Abandoned America or listen to his Abandoned America podcast.

-Baldur’s-Gate-3-The-Final-Patch---An-Animated-Short-00-03-43.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)